We stay at the South Street Chapel to contemplate how the Wesleyan Methodists fought amongst themselves

Ilkeston’s Wesleyan Reformers

The ‘Fly Leaves’ did create tensions within the Wesleyan Methodist community and caused much recrimination and bitterness. Ilkeston was not immune to these feelings.

Many Ilkeston Wesleyans – let us call them the ‘Wesleyan Reformers’ — protested at the expulsion of the three ‘Methodist Martyrs’ and on Monday, August 20th 1849, a meeting was held at the Wesleyan School Room to discuss the expulsions. It was chaired by Henry Carrier, a member of the Wesleyan Society for 50 years, a Trustee and Leader, and father of Joseph and Samuel. The outcome was to vote against the expulsions and to set up a contribution fund to help support the three ‘Martyrs’.

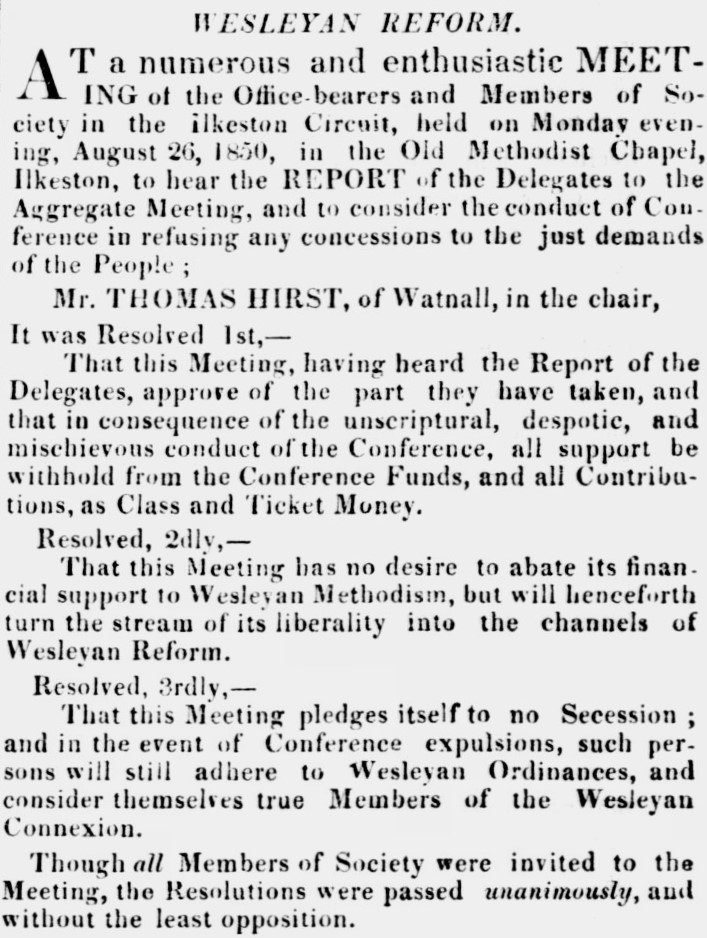

In the following year, on March 29th 1850, a further, crowded meeting of Reformers was held at the Independent Chapel in Pimlico, again chaired by Henry Carrier, and at which William Griffith and James Everett were guest speakers. At the same time, and before an audience of about 20 persons, the very Rev, George Buckley, the Wesleyan Minister at Stapleford, was using the South Street Wesleyan Chapel to preach to a depleted congregation of “non-Reformers”. The figure of ’20’ audience members was contested vigorously by the Rev. Buckley who insisted that there were ten times that number in the South Street chapel … though Samuel Carrier, trustee and chapel steward, counted the number to be 61 exactly !! Some of those who had been queuing at the Old Chapel to hear William Griffith had walked over to the New Chapel when it was obvious that they wouldn’t get in to their ‘first choice’. Later, on August 26th, 1850, a further meeting of Ilkeston’s Wesleyans, held at the Old Chapel, confirmed what the meeting almost exactly one year earlier had decided; that the Ilkeston branch would not financially support the Wesleyan Establishment but would spend all its funds in support of the Reformers.

from the Nottingham Guardian (August 30th, 1850)

However the retaliation of the ‘Establishment’ Conference to the ‘Reform Movement’ was abrupt, and contributors to the Reform fund were dealt with severely, with expulsion. The Conference was now ready to send in its “big guns” to deal with lkeston’s rebel Reformers.

The Rev. Hume cracks his whip

One of the men leading this retaliation in the Ilkeston Circuit was the Rev. Alexander Hume, a man determined to suppress disaffection, restore order and reassert the authority of the ’Establishment’.

In September 1850 he planned a visit to Ilkeston and a handbill of the time warned inhabitants of his coming!!

Wesleyan Reformers in the Ilkeston Circuit prepare for Death ! Death ! Death !

The Pope’s legate is come invested with a Star Chamber Commission and armed with the instruments of destruction. He has opened his commission at Long Eaton, and (many Reformers) male and female, by one stroke fell at his feet, and they are no more !

Wesleyan Reformers, gather up your feet and address yourselves to your exit, for the judge is at the door, and his hand has taken hold of vengeance. Give him cheers as he passes through the Circuit; hail him into God’s holy temples as the messenger of death; lick the hand that grasps the sword to slay you; lay your necks quietly on the block, and die like Wesleyan Reformers. (from William Smith)

The Nottingham Review of 1850 describes Alexander’s profile amongst the Wesleyans of the town. He was fiercely unpopular among some sections of the Wesleyan community because of his ‘combative propensities‘ in unceremoniously expelling members from the society, reading what people called the ’Riot Act’ from the pulpits, and in continually ‘breathing out threatenings against all that shall oppose his authority‘.

Every quarter the Wesleyans held a meeting of their Circuit officials and one such “Quarterly Meeting” had been called for September 24th,, 1850, to be held as usual in the vestry of the Ilkeston chapel. These meetings had two purposes. Firstly they were a chance to inquire into the religious and moral qualities of the “local preachers”, and how well they were adhering to the circuit’s “plan”. Only local preachers were allowed into the discussion and attendees had to have a “quarterly ticket”; this ticket could be withdrawn at any time by the presiding minister who had called the meeting. On this particular September meeting, discussion of this topic was scheduled for the morning session.

However several circuit members had previously been expelled because of their support for the “Reformers” and yet they had turned up for the meeting without a ticket !! Consequently they were asked, several times, to leave, but consistently refused. A ‘stand-off’ ensued, that is until the meeting was adjourned, but hastily rearranged, in the parlour of the presiding minister.

The second purpose of these meetings was of a financial character, to consider how well the local preachers were obeying certain financial orders. And the same rules of attendance applied to this aspect. The meeting was to be held later in the day, once more in the minister’s parlour, but once more he was besieged by ‘ticketless’ members. He saw this as a blatant trespass on his private property, and after much fuitless pleading and arguing, George Small, the parish constable, had to be summoned and use his authority to ‘oust’ the interlopers.

Shortly after this, on October 27th, Alexander arrived in town to preach in the new South Street chapel while, to show the extent of their opposition to him, a number of ’rebels’ held a public service and Sunday school in the old Cricket Ground chapel. The reverend gentlemen thus tried to preach at the old chapel too but he was physically barred from doing so. When he tried to address the scholars there, they made noises to drown his voice. He was forced to retreat to the new chapel, ’saluted by the hootings of the more thoughtless part of the populace’.

Numbers dwindle

By 1850 such confrontations and treatment had caused the Ilkeston Circuit Wesleyan Methodists to lose three-quarters of its members to the Reform movement.

The conflict also had its effect upon the Wesleyan Missionary Society. In November 1850, after two sermons at the South Street Chapel, collections were made on behalf of the Society and raised only £4, an unusually small amount. The reason for this was the mistrust among the ‘Reformers’ in the secretaries of the Society who refused to open their expenditure books for scrutiny. There was a feeling that the income from donations, which amounted to over £100,000 nationally, was being wasted and used extravagantly. All this money was in the care of just four secretaries who kept their expenditure a closely guarded secret (or so it was claimed).

The two seperate issues in March of 1851 highlighted the continuing fractious nature of Wesleyan Methodism in Ilkeston, and the relative ‘strengths’ of the opposing sides in the dispute.

On March 17th, 1851, a scheduled meeting of the Wesleyans, held at Kimberley, reported that, of the 10 chapels in the Circuit, four of them were occupied by Reformers while others were ‘sympathisers’. In Ilkeston, the old Cricket Ground Chapel was being used by the Reformers who preached to ‘packed houses’, while the new chapel in South Street, used by Conference preachers, catered for a very small congregation. And in many other places the Reformers staged alternative services to those of the ‘Establishment‘ with similar results.

Then, on March 30th, a census of places of worship was taken, in addition to the National census of population. Among other detail this Religious census requested figures of attendance, as well as average attendance numbers for the previous year, from all churches and chapels. The effects of the split amongst the Wesleyans in Ilkeston could clearly be seen in this census. It reported that a relatively small group of the Wesleyan Methodists was still at the new South Street Chapel, “separate and entire, exclusively used, .. in lieu of one erected before 1800” (the ‘one erected before 1800’ was the Old Cricket Ground Chapel). With accommodation for 530 persons, the actual Sunday morning congregation was 35, a morning Sunday School of 30, with an evening congregation of 50. However the average morning attendance is given as 120 with an evening attendance of 150 and a morning Sunday School of 170. A note added by Alexander Hume, who supplied these statistics, states that ‘the usual Average attendance has been lately affected by certain temporary local circumstances’. In November of 1850 the Rev. Hume had written to John Beecham, President of the Methodist Conference, to explain these ‘temporary local circumstances’…

“such is the state of anarchy and disruption in which we found the circuit, we have not been able to take any account of who are members and who are not, so that for the last quarter the Schedule Book is a blank. With the exception of one or two only of the congregations, all the congregations in the circuit are the most disorderly riotous assemblies of wild beasts: and the pulpits regularly the spit of contention between the authorised local preachers and those patronised by the mob. I have instructed the Brethren on the Plan (i.e. the local preachers) to retire quietly from the ungodly contest when they have claimed their places…. I do not think it right to be any further a party to the desecration of all that is sacred on God’s day, by contending with infuriated men, some of whom have again and again, squared their fists in my face in regular pugilistic style and all but struck me….” (Quoted by W. R. Ward in Religion and Society in England. 1790-1850 (1972), p269)

The same 1851 Religious Census showed the Ilkeston Wesleyan Methodist Reformers still at the old Cricket Ground Chapel, with much healthier attendance figures. The chapel had accommodation for about 370 persons, an actual morning congregation of 100, a morning Sunday School of 170, an afternoon School of 250, and an evening congregation of 350. (No average attendance was given and the figures were supplied by steward Samuel Carrier).

However the ‘local circumstances’ were far from temporary, as Alexander Hume hoped.

Unable to maintain them financially, the Ilkeston Circuit had to give up most of its chapels to the ‘Reformers’ — except in New and Old Brinsley, Eastwood, Stanley and Sandiacre. Cotmanhay, Stanley Common and Kimberley lost their chapels and their entire membership, while Long Eaton and Stapleford lost the chapels but retained some members.

In Ilkeston the ownership of the South Street Chapel was disputed and it seems that as late as December 1853 was jointly used by the Reformers and the Old Wesleyans. By the beginning of 1854 however, it was occupied by the Wesleyan Reformers (the Methodist Free Church), leaving the ‘Old Wesleyans’ out in the cold, with no chapel home. Before it was handed over, their minister preached to “a feeble remnant, the melancholy wreck of a good congregation”.

The old Cricket Ground Chapel in Burgin’s Yard was thereafter used by the ‘Reformers’ as a Sunday school. Whilest, by 1855 the old Ilkeston Circuit was reduced to less than 200 members and five old chapels.

The United Methodist Free Churches

Some years later, in 1857, many but not all of the Wesleyan Reformers merged with other smaller breakaway groups to form the United Methodist Free Churches.

According to Adeline it is this group that stayed at the Cricket Ground Chapel while the ‘Old Wesleyans’ built the South Street Chapel.

There appears no other evidence to support this and Adeline is misleading when referring to the United Methodist Free Church in the late 1840’s and early 1850’s.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

But where were the ‘Old Wesleyans‘ to go after their move out of the South Street chapel?