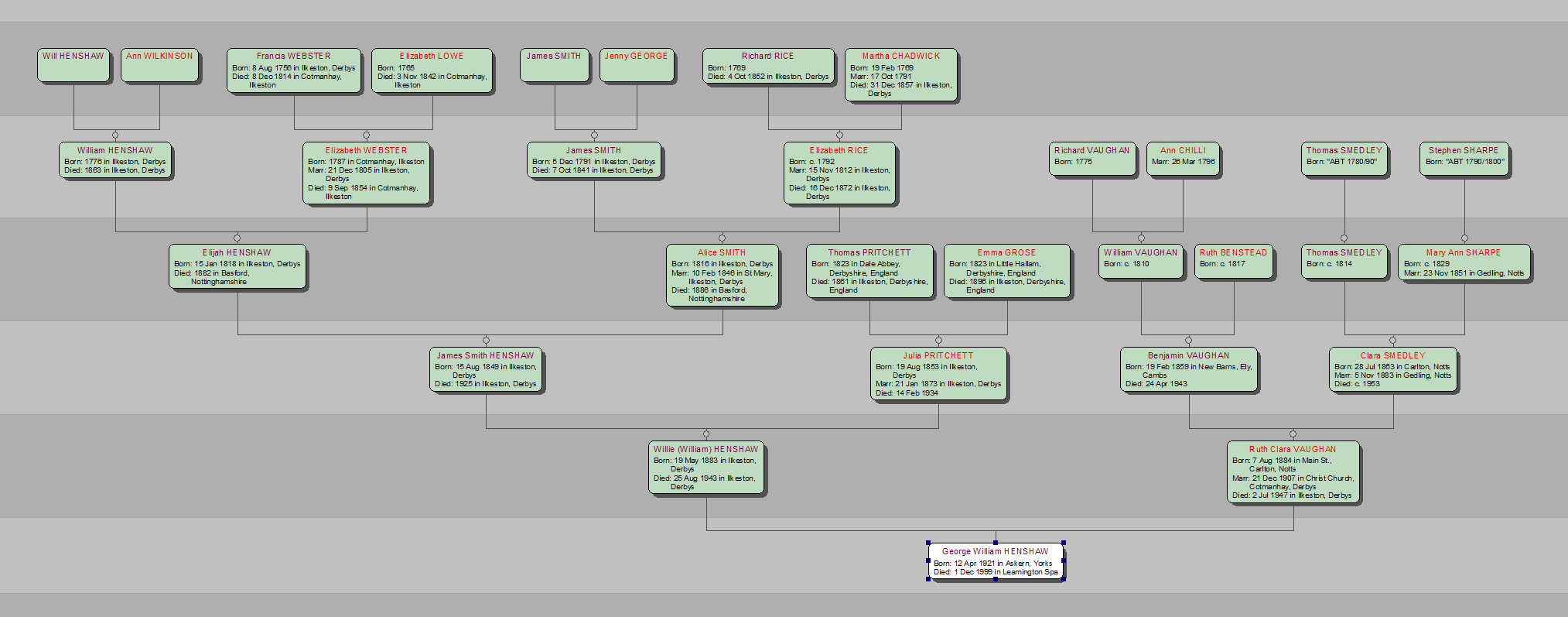

This excellent and thorough Henshaw story has been researched by Rick (Richard James) Henshaw who is a grandson of William and Ruth Clara Henshaw.

The Henshaws in Charlotte Street

George Henshaw was born on April 21st 1921, the son of William Henshaw, christened Willie to distinguish him from an older brother who died young, and Ruth Clara Vaughan. William was born in Ilkeston on the 19th of May 1883 while Ruth’s family lived on Main Street Carlton some 10 miles away when she was born on 7th August 1884. William and Ruth married at Christ Church, Cotmanhay on the 21st December 1907. The marriage was witnessed by Benjamin Vaughan (probably Ruth’s brother, but it could have been her father) and Lily Henshaw (William’s sister). Both William and Ruth gave their addresses as Charlotte Street Ilkeston and William’s occupation is recorded as Lacemaker.

William and Ruth’s first two children were born in Ilkeston – Florence Edith (b. 1908), known as Edith and James Frederick (b. 15 February 1912), known as Fred. 28 Charlotte Street is the address on Fred’s Birth Certificate.

War-time and a move ‘up north’

At the start of the First World War, there was a steep decline in the lace trade, and a severe lack of jobs of any sort in the Derby and Nottingham areas. But there was a shortage of men in the coal mines in Yorkshire, and recruitment teams used to come down to Ilkeston encouraging people to move and take jobs there. William Henshaw’s father had been a collier, and the Henshaws decided to move.

By February 1915, when Ruth’s brother Benjamin Vaughan wrote to her thanking her for the cake (!), their address was 52, Park Road, New Village, Askern, nr Doncaster. There William started a new career in the Collieries. This was still their address when Arthur was born later that year, and indeed in September 1916, when Fred was about to start school. By the time George was born in 1921, their address was 1, Station Road, Askern, and William’s profession was Colliery Deputy.

Mining Committee – 1920s. William Henshaw is on the right in the front row.

Post-war life

Ruth Henshaw was very active in the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade, and was Lady Divisional Superintendent of the Askern Nursing Division, from May 1917 until the Henshaws moved to Thurcroft near Rotherham. There she became Superintendent of the Thurcroft Division. The address given on the St John’s headed letter paper in 1928 is Steadfold Road, Thurcroft.

St John’s Ambulance Askern Nursing Division – 1920s. Ruth Henshaw is on the left in the front row

Back to Ilkeston … but a change of life.

It was not long after that, in about 1930, that the Henshaws moved back to Ilkeston. They lived at 30, Archer St. and William worked at the colliery near Cotmanhay. Then, using some of the money he had made over the years as a Collier, William bought a fish and chip business in St. Mary St., Ilkeston. They lived at no. 13, next door to the shop at no. 14. In about 1938, William was able to buy his own house at 24, Whitworth Rd., Ilkeston, where he and Ruth lived until they died, William in 1943, and Ruth in 1947. They sold the fish and chip shop at around the same time and William returned to work as a lacemaker but with the advent of WW II, once again the lace trade collapsed. William took a job at the Ordnance Depot at Bondswell and worked there until he died. The house then passed to Edith, who became a school teacher and married Ronald Spiby in 1936 in Ilkeston.

George first went to school in Thurcroft and then, when the family moved back to Ilkeston, moved to Granby Infants and then Granby Juniors.

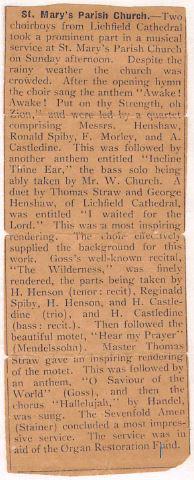

He used to take the tram to the parish church, St Mary’s, Ilkeston, to sing in the choir.

It was his singing that changed the shape of George’s life.

We don’t know exactly how it came about, but in 1931 George went to Lichfield Cathedral choir school.

There, in his own words, he learnt to sing extremely well but not much else.

The brothers Henshaw … Fred, George and Arthur outside Lichfield Cathedral

A newspaper cutting, probably from a 1932 edition of an Ilkeston paper, describes a concert at St Mary’s Church at which George performed alongside his brother-in-law to be, Ronald Spiby and his brother Reg.

The latter left Ilkeston in 1933 to live in Arnold, so the cutting is thought to be before then.

By 1935, George had decided that he wanted to go into the ministry.

The Praecentor of Lichfield cathedral had looked into ways for him to do that on leaving Lichfield, but all possibilities were too expensive, except perhaps by going to college at Newark once he was eighteen.

And so at age 14, George left the choir school and was due to start work as an office clerk in the Ordnance Depot at Bondswell in April 1935.

Enter Spencer Madden and Allen Moxon

But before that, a visit to George’s parents changed things very quickly. One regular attender at Lichfield Cathedral services was a man named Spencer Madden. He was unmarried, and lived with two of his sisters in a large house, about half a mile from the cathedral. He was a good friend of the choir school, and used to allow boys to come to his house, to take tea, to play snooker with him, and to play in the grounds of his house. Spencer Madden thought it wrong that George should become an office clerk, seeing more potential in him and arranged to visit George’s parents in Ilkeston, to “make them a proposal concerning George’s education”.

When he arrived at St. Mary St., George was sent into the back room while the discussion took place. The proposal was that he would pay for George to go to Denstone College, then to Oxford to study Theology and thence into the ministry. George’s parents agreed, and a few days later the headmaster of Denstone came to St Mary St. to meet George.

When George sang in the choir in Ilkeston, two other boys had left to go to private schools where the headmaster was a minister, something that George thought unusual. So when he arrived at Lichfield he was particularly interested in one prebend (of 30 or 40 who came to the cathedral for Chapter Meetings). He was Allen Moxon, the Headmaster of Denstone College. When Allen Moxon started the interview with George by introducing himself and said “You don’t know me”, George was able to say “Yes I do!”. The interview went well and, rather than wait until the next academic year, the headmaster was keen that George start at the school immediately and begin the process of catching up on his general education as soon as possible. The decision was taken on Wednesday. Allen Moxon left a list of everything George would need, and over the next three days his mother organised them all. On Friday he was ready for school, with all of his uniform, kit, and other equipment ready and labelled, and Spencer Madden collected him from St Mary St. and delivered him to Denstone by car.

College life

George was in Heywood House at Denstone College for five years, leaving in 1940.

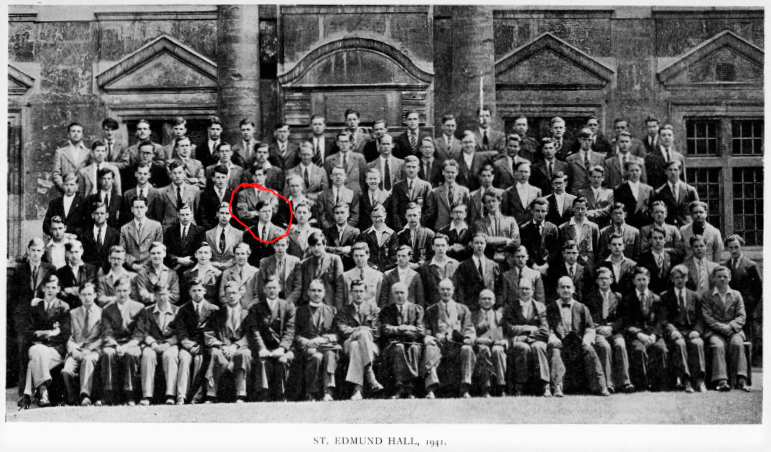

He made rapid progress and shone both academically, getting nine credits in School Certificate after three years (the maximum possible), and on the athletics track where he was Victor Ludorum in his last year. He took the entrance exam for St Edmund Hall, Oxford on the 16th April 1940 and went up to Oxford to study Theology in October of that year. As was the way in the war years, he studied for four terms before being called up.

For all four terms he lived in the college or close by (Room 57 (or is it 51?) for his first 3 terms in 1940 and 41, then a term a few hundred yards away in 57 High St, close to the

junction of the High and Longwall St).

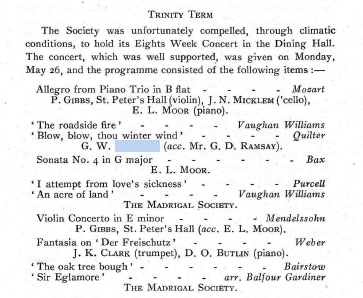

Music and sport seem to have dominated those four terms. The college magazine for 1941 records George’s involvement as Secretary of

the Gramophone Society, the Rugby Club and as a singer in Musical Society concerts.

It does not record an achievement of which we know he was very proud; he was Junior Common Room shove-halfpenny champion in 1941.

In Michaelmas term, when George was Secretary, the magazine Rugby report records that “throughout the term five players from the Hall and Queen’s have been playing regularly for the Varsity XV, and two for the Greyhounds.”. George was one of the two Greyhounds, the University second XV, for whom he played on the wing.

You’re in the Army now

In January 1942, he caught the train to Officer’s training near what is now Alton Towers on a very snowy day. At the station, the cab could not take all of the newly arrived cadets from the station, so they sent their luggage and walked, taking a short cut across the fields that George knew from his cross country running days at Denstone College, arriving at about the same time as the taxi.

At Alton Towers, the officer cadets were taught the jobs of all the various roles in the Royal Artillery.

In George’s words “We needed to know every man’s job if we were to be officers in charge so I learnt signalling and I learnt the mathematics of gun laying and all about petrol engines and lorries. And at the end of the six months I was sent to a Regiment.”

“I was saying about the training. We learnt the drill stuff, how to lay a gun, we used to practise and practise and practise practically every day and the men who taught us were Sergeants, who taught us the gun drill and they had to be very fierce with us which seemed to be the way they wanted it …. and they didn’t call us… we hadn’t got any rank, we weren’t even Privates or anything, we were simply cadets. We were called cadets and …. the Sergeants who were teaching us all the drills and the automatic stuff always called us “Sir” – although we had no rank and they were Sergeants they always called us “Sir”.”

“If you did anything wrong in the gun drill, learning the gun drill or handling gun laying, if you made a mistake the Sergeant would tell you to put your gas mask on, which you’d got with you, and to pick up pieces of ammunition –25 lb each, one under each arm and run round the gun park. This was to help you to remember …. And I remember somebody made a mistake and I heard this voice say “Round you go Mr Foggerty…..Sir” ….always “Sir on the end.”

At the end of six months, the cadets were sent to a Regiment. On 14 Feb 1943, George sent a letter from 516 Field Battery RA, 178 Field Regt RA, GPO Felixstowe, Suffolk to St Edmund Hall apologising for being late in paying a bill.

War Diaries

Turning to the War Diary of 178 Field Regiment, the opening entry for New Year’s Day 1943 the regimental diary records “Move to Felixstowe completed”. Other than Officers’ shooting parties and a boxing tournament, January and February seem to have been uneventful but on March 14th it records “Liverpool Embarked” followed on March 27th by “Freetown Arrived”.

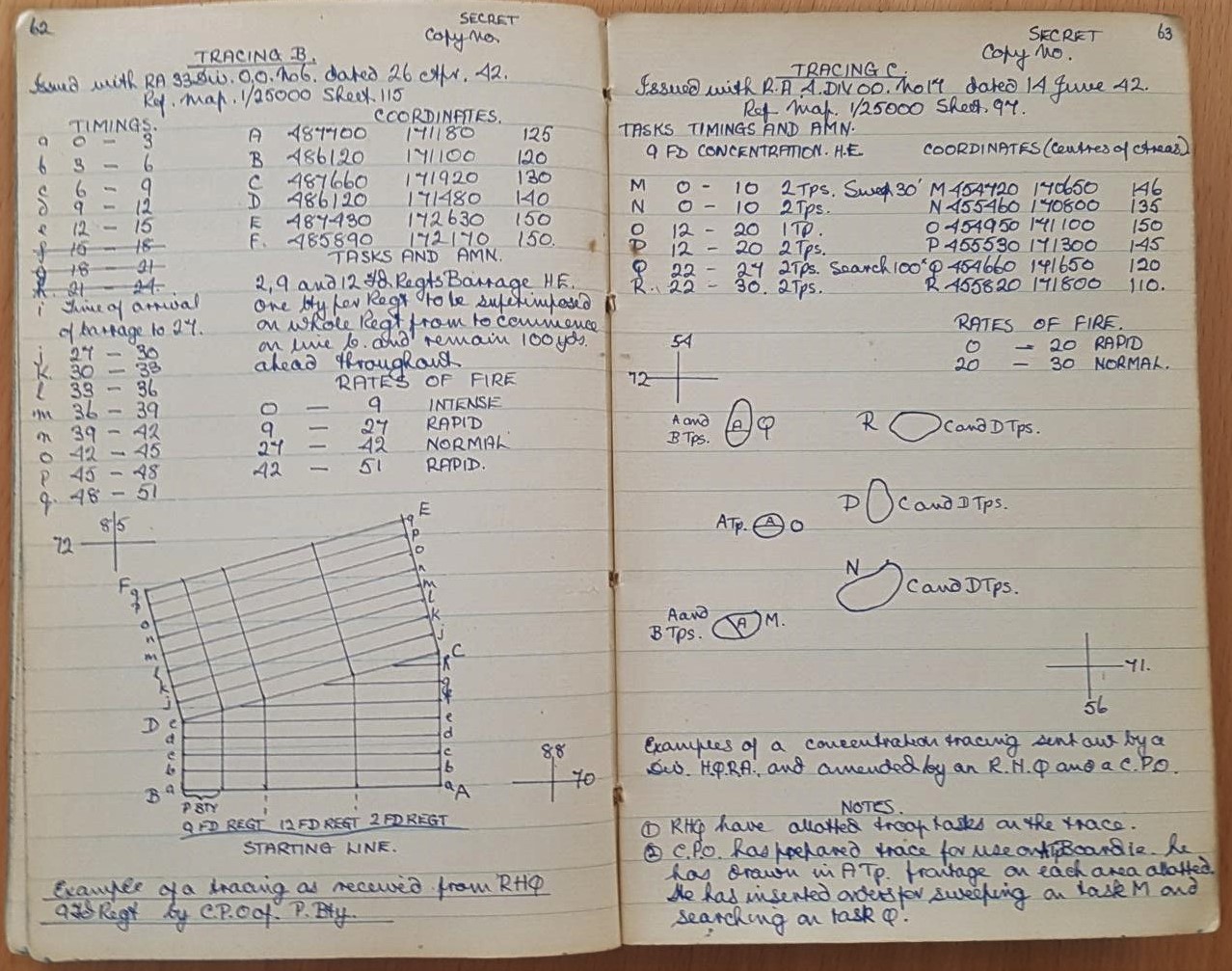

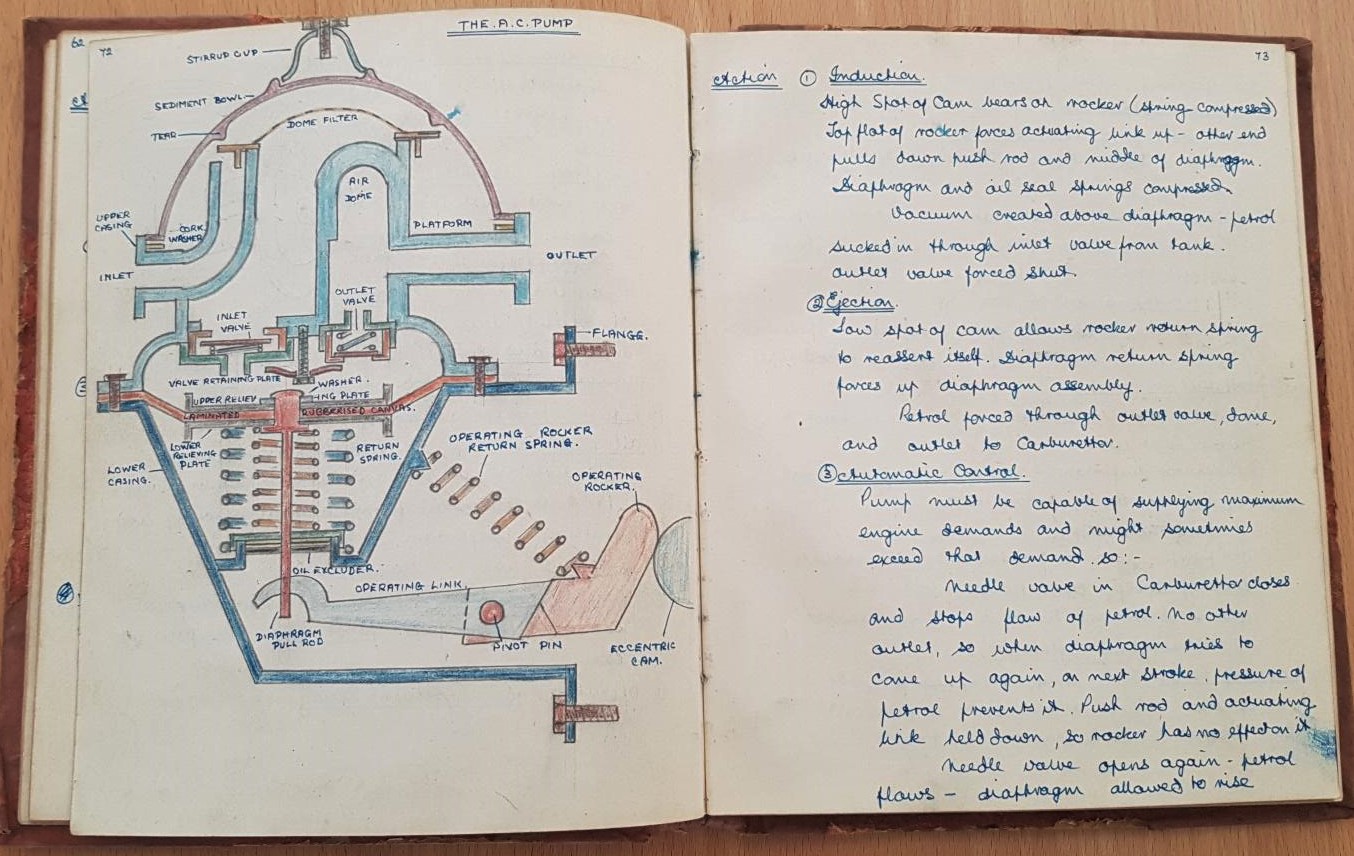

Henshaw’s Artillery Manual 1941

Drawing of AC petrol pump, George Henshaw’s training notes 1941

While the entries in the Regimental Diary for this period are best described as terse, day to day life in Felixstowe with 178 Field Regiment RA is described in some detail in “The Forgotten Army: a Burma Soldier’s Story in Letters” in which James Fenton publishes 440 letters to his parents spanning his time in the army at home, in India, Burma and Malaya together with drawings, paintings and photos. From James’ letters, we know that 178 Regiment RA left Liverpool on the Cunard White Star Line MV Britannic, a converted luxury liner, joining a convoy of ships under the protection of the Royal Navy. Once at Freetown, the MV Britannic stood offshore to take on water and fresh supplies on the way to Capetown, for which it left on March 30th, arriving on April 11th.

After disembarking, some of the troops were given the task of searching Italian PoWs captured in North Africa who were waiting to board the newly arrived ship. The soldiers stood in line and the Italian prisoners filed in and stood each facing a soldier whose job it was to search each prisoner and their belongings for matches, knives and any other dangerous or suspicious objects. Then it was on to the Imperial Forces Transit Camp at Retraat on a sandy plain near Pollsmoor, 9 miles from Capetown, now the site of a top security prison. There the Regiment stayed until setting off for Bombay on May 22nd on the troop ship SS Orbita.

To the East

After a brief stay in Bombay, the regiment left for Cantonment Station, Bangalore on June 13th and travelled on by lorry to Tarbanhalli Camp15, some 15 miles outside Bangalore itself. A month later on July 17th the regiment travelled by train from Bangalore to Poona, arriving at Kharakvasla camp on the 20th.

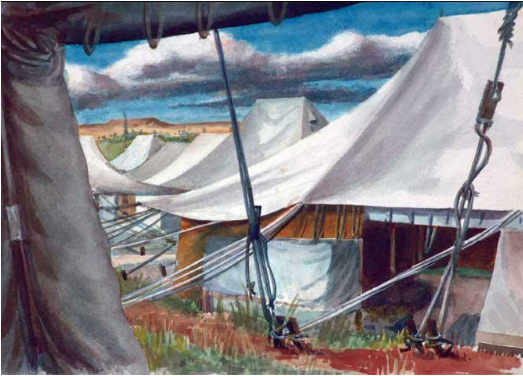

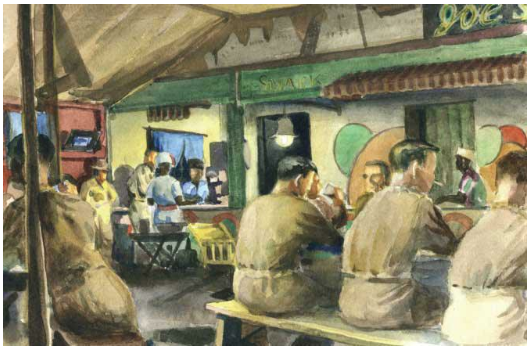

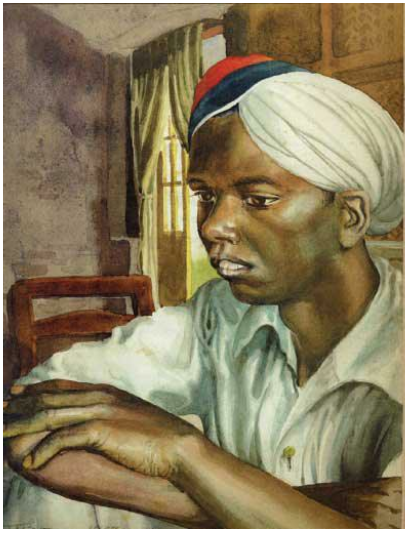

These illustrations are from James Fenton’s book.

Kharakvasla Camp, Poona, – Fenton, James. The Forgotten Army

Joe’s Canteen, Kharakvasla Camp, Poona, – Fenton, James. The Forgotten Army

Sawa, Canteen Bearer Kharakvasla Camp, – Fenton, James. The Forgotten Army

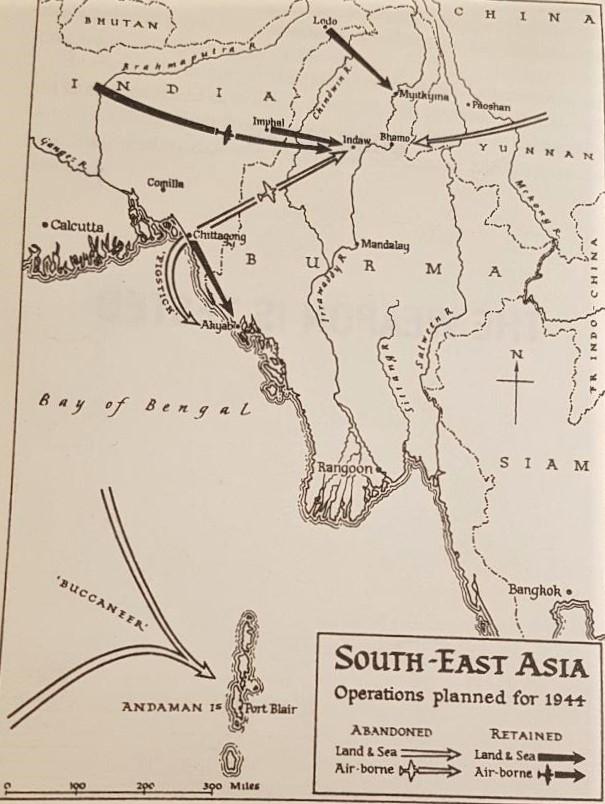

The camp at Kharakvasla was near to a deep water lake contained by a large dam, with ideal facilities to practice assault landings from small boats. Some of the 25-pounder field guns (particularly in 366 Battery) were replaced with 3.7-inch Howitzers; lighter guns, more adaptable for use in assault landings and close jungle warfare and much of the time was spent in training for sea-borne attacks on Japanese forces. At that time, the target was the coastal town of Akyab, but events elsewhere soon changed that.

In his excellent book “Defeat into Victory” General Slim writes of his concerns about the 1944 offensive and on p268 says “General Giffard…..also cheered me very much by telling me that he would order the 36th British Division from Calcutta into Chittagong to replace the 26th Division if I had to move it south”.

And that is exactly what happened; The Japanese infiltrated and attacked the HQ of 7th division and the Battle of the Admin Box followed from 5 to 23 February 1944. Rather than retreat, the Allied troops changed tactics and held their ground even though they were surrounded. Supplies came in by air and the Japanese, who had relied on capturing British supplies to feed themselves, starved; the besieged starved out the besiegers and set a new pattern for the rest of the war in Burma.

The 26th Division were in the Arakan and got caught up in relieving the Admin Box, and the 36th Division was duly mobilised. In February, the regiment set off for Chittagong from Calcutta Docks on the SS Jalagopal (launched 1911 as SS Edavana), and on from there to Cox’s Bazaar by paddle steamer before completing the trip to the Arakan by road.

Passing through Cox’s Bazaar a few weeks later than George, the father of journalist Alyn Shipton described it thus:

”The village was a couple of streets with a few shops which, surprisingly enough, included an expensive watch and clock repairer. The camp to which we were allocated was virtually on the beach, and it was possible to bathe in the sea although there were huge rollers when the weather was windy and vicious undercurrents at all times. The journey from Chittagong to Cox’s, by steamer, could be very pleasant or wicked according to the time of the year. In the winter it could be a delightful trip down the Bengal coast, but in the Monsoon the little boat bobbed about like a cork and you were liable to get soaked by the rain. Whichever end you started, the boat usually left just before dawn; in the winter it was relatively cold at that time of day, and in the summer usually dark and forbidding with heavy rain clouds threatening to break, and the swollen river gurgling sullenly by.”

The Arakan’s coastal plain is separated from the Kalapanzin valley (and the Admin Box) by the Mayu Range of hills which rise to around 2,000 feet.

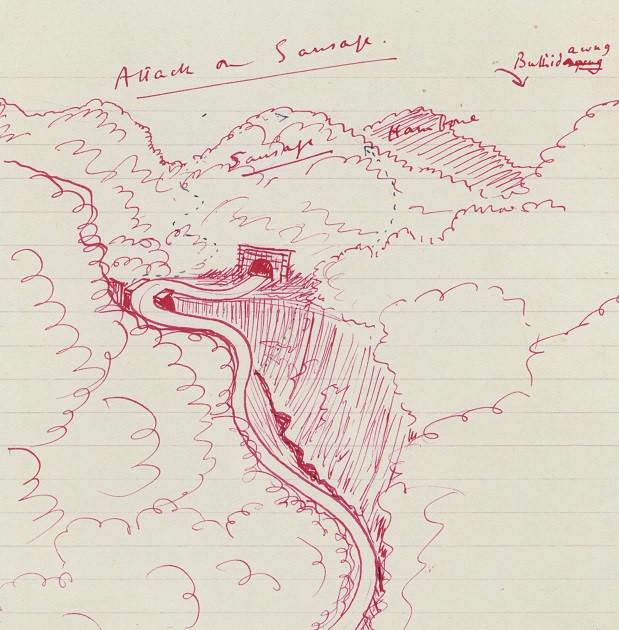

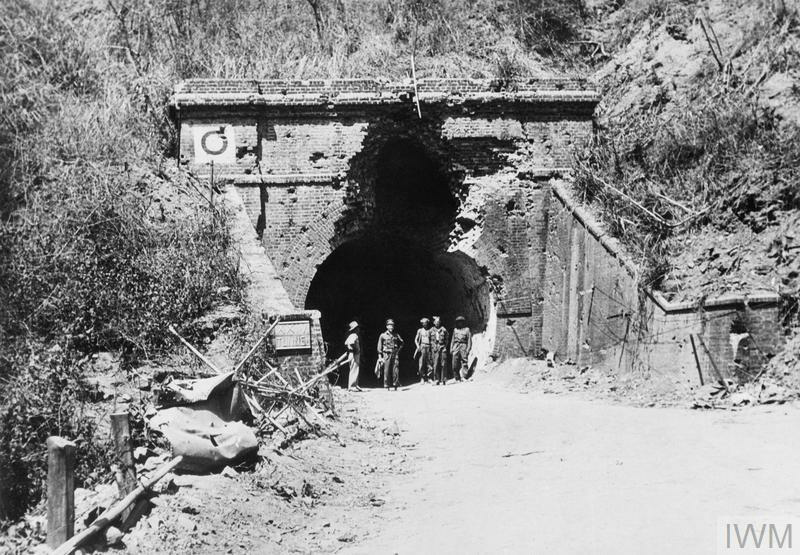

The main road through the Mayu Range had originally been designed as a railway and ran through a series of tunnels from Maungdaw to Buthidaung on the Mayu River. The Japanese were in control of this road and so could pass men and supplies quickly from one side of the Mayu hills to the other, and used the two Mayu tunnels for storage and gun emplacements.

Fighting in the Arakan and around the tunnels was among the most bitter of the entire Burma campaign and 178 Regiment bombarded the hills around them, many known by quaint names such as Sausage, Tortoise and Hambone, for several days.

Eventually, in early April, the Japanese were dislodged from the second tunnel when a Sherman tank was brought up to fire into the mouth of the tunnel.

Bodies and debris were blown out of the other end of the tunnel and ammunition stored inside exploded and burned for hours.

Fighting in the area continued until mid-April but, as the monsoon began, it was found that the low-lying area around Buthidaung was malarial and unhealthy and the Allies actually withdrew from the area to spare themselves losses to disease. By mid-May the regiment was in the Indian hill town of Shillong.

Akyab remained in Japanese hands until January 1945, when a renewed Allied advance combined with amphibious landings drove the Japanese from the Arakan, inflicting heavy casualties by landing troops to cut off their retreat down the coast.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

We now walk down Albion Place, back into Burr Lane, and examine the cottages on the west side of that lane.