Some, but not all, of the following has appeared elsewhere on the site … it is brought together here. It is not a comprehensive history of the town’s drinking habits,

A few terms of clarification for non-drinkers — and drinkers —

Since the 15th Century an Inn suppied food and drink, accomodation for travellers, and stables for horses; a tavern offered just food and drink, while an alehouse brewed and sold beer and ale, but had no license to sell spirits.

A victualler provides food and provisions for customers while a licensed victualler has a licence to provide alchoholic beverages also.

The Alehouse Act (1828) gave local magistrates complete control over the granting of licences to sell ale etc. The grant was made at the Brewster Sessions, a general annual licensing meeting, and a licence was granted if the licensee promised not to adulterate his liquors, used legal measures, didn’t permit drunkenness, gambling or disorderly conduct on his premises, and made sure he was closed during Divine Service on Sundays, Christmas Day and Good Friday.

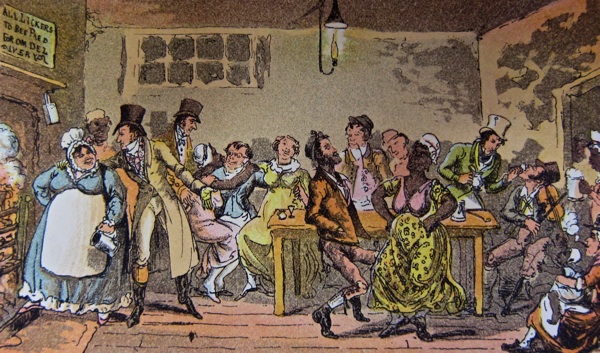

Under the Beerhouse Act (1830) there was now no need to apply to the local magistrates for a licence to sell certain types of liquor, mainly beer. Any householder assessed to the poor rate could purchase an excise licence from the local excise officer for a modest price — initially two guineas (£2 2s) per year — and then commence to brew and sell beer, ale and cider from his own premises, either on or off. Hence we see the appearance of the beer house. In the first three months of the Act being passed 24,342 licences were issued; these new ‘houses’ were named as “Tom and Jerry shops” after two dissolute and rakish fops of that era.

Tom and Jerry in London in the 1820s

The Act also extended opening hours to 18 hours per day, usually from 4am to 10pm. However the Beer retailer found it hard to compete with publicans who were allowed to sell spirits too; so they often adulterated their beer in order to sell at lower prices, and permitted all sorts of conduct on their premises to attract custom.

In 1834 the Act was slightly modified — a distinction was made between ‘on’ and ‘off’ sales, and anyone who wanted to get a licence to sell beer on the premises had to produce a certificate of good behaviour signed by six rate-paying members of the parish.

By 1840 there was a concern that too many beerhouses were being set up, and so to slow down the growth another modification was made. A new licence for both on or off sales would only be granted if the premises had a specified annual value and the licence-holder had to live in the house.

And this situation lasted until 1869 when we get another new Licensing Act. Once more Justices were granted the sole right to issue licences, and an alehouse keeper had to have a Justices Licence before he could obtain an Excise Licence to sell his beer. This applied to both on and off sales.

Now is that clear ?!

Ilkeston’s Public Houses at the dawn of the Victorian Age: 1837

Here is a list of Ilkeston’s public houses as the town entered the Victorian Age, with the name of the landlord/s and location. Among other sources, I have used Gauntley’s Enclosure map and survey of 1798, his later Survey of 1817, the Register of Victuallers licensed in Ilkeston 1818-1827, several Trade Directories, and the 1841 Census to compile the list below. Those named in bold black appear in the Register of Victuallers; those in bold red do not appear in the Register — so I am assuming that they did not exist as licensed premises until after 1827.

Ancient Druids … At Cotmanhay, it was occupied by Robert Booth.

Boatswain … At Bottom Road/the Pottery; this appears on the 1798 map, owned by Thomas Potter who was still the owner in 1817 though the tenant was William Rhodes. By 1818 William Burgin Richardson had taken over as landlord and then he was followed by his son James (at the death in 1830 of his father William, who was the brother-in-law of Mark Attenborough). For a short time he was helped by his mother Elizabeth (nee Attenborough) until she left for West Hallam, to live with daughter Marina.

Bull’s Head … At Little Hallam; the pub premises appear on the 1798 Enclosure Map (though perhaps not under the Bull’s Head name) owned by Isaac Atkins and his wife, who had just moved from the Anchor Inn in Lower Market Place. About 1805 Isaac sold the property to William Bower, with the latter’s son Thomas as landlord. Thomas occupied this until the late 1830’s when he went off to farm at Stanley. On the 1841 Census James Syson is landlord.

Harrow … In Lower Market Place; it appears on the 1798 Map, owned by Gilbert Walker and by 1817 was owned by William Blunstone, with William Severn as landlord. The landlord died in 1818 and for a few years it was in the hands of his widow Phoebe Severn (nee Leggitt) until she remarried in 1822, to Thomas Bennett who then became landlord.

Horse and Jockey … at Gallows Inn; it appears on the 1798 Enclosure Map, owned by Thomas Hunt who died in 1812. In that year it was purchased by John Lowe who was landlord until the mid-1830s when suceeded by Edward Severn though it was still owned by John Lowe. The latter died, unmarried, in 1837 and the inn passed to his brother Christopher Lowe but with the same landlord

King’s Head … In the Market Place; there is no evidence of it on the 1798 or 1817 Surveys. However in the late 1820s it had landlords William Jackson (up to about 1830) then John Bates (up to about 1839) and then William Woodruffe

Peacock … At Cotmanhay; Mary Knighton (nee Jackson), widow of Joseph, was landlady until her death in 1833 when Ralph Buckland, her nephew, took over

Queen’s Head … In Bath Street; Benjamin Wade was landlord until the late 1830s, followed by his son-in-law William Moreland, (second husband of Sarah Wade)

Rose and Crown … At Cotmanhay; from 1821 it was occupied by Thomas Noon, and then in the 1830s by Joseph Aldred (whose wife Amy Knighton was the sister of Thomas Noon’s wife Ruth)

Rutland Arms … In Bath Street; from 1818 (at least) it was occupied by the Hives family, first by John, and then by son Thomas (probably after John’s death in 1834)

Sir John Warren … In the Market Place; on the 1798 Survey the property is owned by Isaac Attenborough, though described only as two houses and a garden, not a public house. Some time between then and 1818 it was converted, so that Isaac was the first landlord. In 1819 his son Mark took over the Inn.

Three Horse Shoes … In Moors Bridge Lane (later called Derby Road); from 1825 William Rowliston was landlord.

White Lion … In Nottingham Road; it is included in the 1798 Map and Survey as a public house owned by Henry Skevington; James Wilson was landlord at least since 1817.

There was also the Wine Vaults in East Street, although this was classed as a ‘Wine Merchant’.

On the 1798 Enclosure Map the old Anchor Inn is also shown; this was on the east side of the Lower Market Place and was owned by Thomas Bradley junior, though in 1799 he sold it to John Shaw of Trowell. In 1825 the premises (no longer an Inn) were acquired by Matthew Hobson.

You may think the above list is incomplete as it doesn’t contain names you are familiar with. However, remember that the list doesn’t include beerhouse/alehouses, a different ‘species’ of drinking establishment.

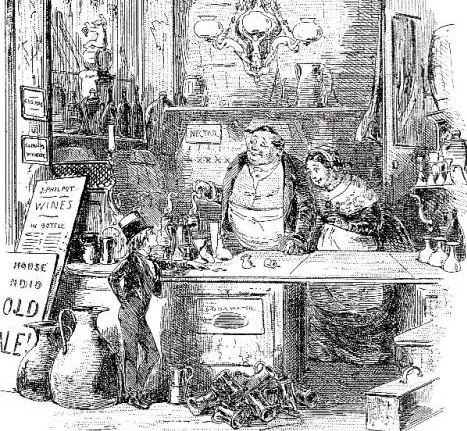

A public house about 1850 (Philip V Allingham)

Public Houses into the 1850s …

In the year of Adeline Columbine’s birth — 1854 — the Nottinghamshire Guardian included a short paragraph from the ‘Builder’ periodical under the heading of ‘Public Houses’.

“As the term denotes, these establishments are open for public accommodation, and the law makes it imperative on the owners holding licence, to give hospitality; besides that, it imposes on them other duties not of an agreeable nature, such as billeting soldiers, receiving the bodies of suicides, &c; they are restrained from receiving customers during divine service, but are forced to admit them at other times; they are heavily amerced for suffering brawls or bad characters to congregate; and (will it be credited !) they are subject also to serious penalties for adulterating liquor !”

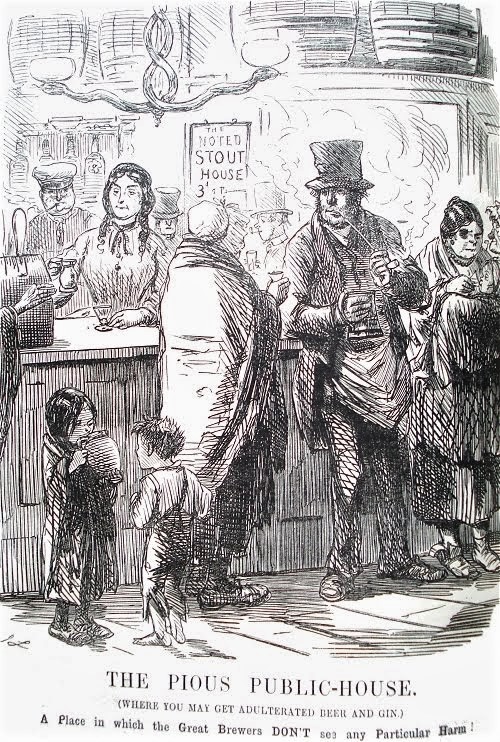

A cartoon from Punch

“What an arduous office the publican has to perform.

“And still, notwithstanding all this, we find these houses increasing every year, until at length in England and Wales they number 61,040 as having spirit licence; and including those licenced for the sale of beer only, they amount to 101,953; being in excess of any other trade, and averaging against the whole population in the ratio of one public-house for every 120 souls! 102,000 public-houses for 12 millions of people! How many churches are there? The latter are built at an enormous national cost, and yet do not accommodate one-half of the population — the former are supported by voluntary contributions, and suffice for all at once.

“The fact is startling, and ought to excite the earnest attention of Government. Whether that attention is bestowed on the subject which its importance demands, is the question. Are these places of rendezvous , of universal and habitual intercourse, at all regarded, except as sources of revenue? Is the quality of the beverage vended ever checked or tested? Or are the proper guarantees for good management duly secured?

“These are points which concern the great moralists of Exeter-hall,* and until they direct their efforts towards the reformation of white slaves (slaves of bad habitudes, of abject condition, and of neglect), at home, chancellors of the exchequer and finance committees, finding them promotive of revenues, in the principal branches of beer, spirits, and tobacco (producing each its five millions a year, will not interfere with them”.

*Exeter Hall in the Strand, London served as a meeting place for the Anti-Slavery Society and other organisations in the 185os. It was also a concert hall.

Ten years after this description, Victuallers’ licenses were being renewed at Smalley Petty Sessions (August 22nd 1864), when it was revealed that Codnor and Loscoe had 9 such licenses, Codnor Park had 1, Dale Abbey 2, Denby 3, Heanor 12, Horsley 2, Horsley Woodhouse 3, Kirk Hallam 0, Mapperley 1, Morley 1, Pentrich 3, Ripley 12, Sandiacre 3, Shipley 1, Smalley 3, Stanley 1, Stanton-by-Dale 2, West Hallam 3 ….. and Ilkeston 25 !!!

Depending upon one’s point of view, Ilkeston was either very fortunate or extremely disadvantaged by its wide choice of drinking premises. And the situation ten years after this wasn’t much changed, as a visit to the Brunswick Hotel, just up the road, will show.

…. and into the 1870s

In May 1874 Edna Annie Davies (nee Woodward) of Lower Granby Street went to the Brunswick Hotel in search of her husband, collier Edward Haynes Davies alias ‘Staffordshire Ted’. Whilst there she was invited to have a drink by a young man and accepted, behaviour which her husband objected to.

To show his displeasure, when the pair returned home, a drunken Edward battered his wife, giving her two black eyes, multiple bruising over parts of her body, and causing her to vomit blood. Edward argued that he had only hit her with the back of his hand and so could not have caused his wife’s injuries.

Less than a week later she died from ‘inflammation of the bowels and peritoneum’. The couple had been married for just over ten months and Edna Annie was aged 20 when she died.

After an extensive inquest held at the Rutland Hotel, at which several neighbours and local surgeons gave evidence, the Coroner’s jury were convinced that Edward was guilty of manslaughter and returned that verdict, with which the Coroner concurred. The husband was then committed for trial at the next Derbyshire Assizes.

The case aroused very strong feelings within the town, none of them sympathetic towards Edward. At the time of the inquest hearing crowds of several hundred persons, mostly women, assembled outside the lock-up at the Town Hall, outside the Rutland Arms, and outside the former home of the deceased. They were in very vocal and riotous mood.

After the inquest but before Edward’s trial a wave of concern and indignation swept through parts of the town. At the junction of Awsworth Road and Cotmanhay Road an open air meeting was held one Tuesday evening, attended by a large and deeply attentive audience – between one and two thousand people the Ilkeston Telegraph estimated – and addressed for over two hours by several local clergymen. Their themes were “the brevity and uncertainty of human life, the importance of young women accepting as their companions in life young men who were religious or at least sober and industrious, and the deplorable evils of intemperance”.

In particular the plethora of public houses within Ilkeston attracted severe criticism, and the feeling of all the speakers and all their listeners was that no more licences should be granted within the town.

At this time there were 62 places in Ilkeston where spirits or other intoxicating drink could be obtained.

At the Heanor Brewster Sessions in September of 1874 – where applications within the district for new licences were considered – two memorials were presented to the magistrates exhorting them to refuse any additional licences for Ilkeston so as not to add to the drunkenness within the town. The source of one of these memorials was the ‘general inhabitants’ and was 16 yards long, with a double column of names, 2644 in total.

At Edward’s trial for manslaughter at Derby Midsummer Assizes the judge directed the jury that if the assault had caused or accelerated Edna Annie’s death then the husband was guilty of the crime. The jury however decided that her death was in no way connected with the abuse and the collier was sentenced to 12 calendar months imprisonment with hard labour for wounding with intent to cause grievous bodily harm.

Ilkeston Town Council and public houses : 1888-1890

On numerous occasions throughout 1888, the Council’s attention and deliberations were drawn towards the town’s Public Houses and liquor trade. I have listed a few here.

The Durham Ox … John Trueman, who operated the brewery in Durham Street called the Durham Ox Brewery, with James O’Hara, paid his Council bill for the making up of Durham Street.

The Anchor Inn (owned by the Crompton Brewery Co.) and the Bull’s Head (owned by William Small) were both found to be without a proper supply of water. The problem with the latter would be solved when it was agreed that a water main should be laid from the Bull’s Head to the new isolation hospital (the Sanatorium), a short distance away on Little Hallam Lane.

The Queen’s Head … the Council had ordered landlord John Trueman (again !!) to install two water closets at the pub. However John had provided an ash pit and two privies instead. After some discussion, it was decided to accept John’s alterations.

The Old Harrow Inn … William Small (again !!) also traded as a butcher and had a shop under the Inn, at 1A Bath Street. The Council resolved to lay on a gas supply for William. And just a short time later, the landlord William Holmes was to be taken to court for non-payment of his gas bill !! (It is unclear whether the two resolutions were related).

The Trumpet Inn … Situated on Cotmanhay Road, it was owned by Messrs Shipstones & Sons and tenanted by James Bromhead. It came under close scutiny by the Medical Officer of Health who discovered that it was in such a filthy and unwholesome condition, as to be a serious danger to anyone within its walls !! He suggested therefore that the walls should be whitewashed and the whole premises be thoroughly cleaned, before it recommenced trading. The Council adopted his suggestion.

The Sir John Warren … the Council agreed to erect a drinking fountain opposite the Inn (below)

Throughout 1889 the Council continued to scrutinise drinking establishments.

The New Inn … The Inn’s water bill hadn’t been paid !! And so, either the owner (James Bonsall) or the tenant (William Trueman), or both, would be taken to court.

The White Lion … The part of Nottingham Road from South Street to the White Lion Inn was to be renamed as White Lion Square.

The Royal Oak Inn … The Inn’s landlord William Booth was fed up with the Salvation Army members and their band gathering opposite the Royal Oak on Primrose Hill. Their playing and singing were created such an annoyance that he was driven to write a complaining letter to the Council. I don’t think that this was the same William Booth who helped establish the Salvation Army !!!

The Needlemaker’s Arms … Wright Lissett, the Town Clerk, was directed by the Council to investigate a charge made by Annie Limb of 58 Wesley Street against Joseph Tatham of the Needlemaker’s Arms (Was he the son of the landlord Herbert ?). It was claimed that on January 15th, 1889, at just after 10pm in the Market Place, Joseph felt the need to urinate on Annie’s dress.

The New Inn … It was resolved that “if the material and rubbish on the footpath against the Inn” was not cleared away pretty sharpish, legal procedings would be taken against the contractors, Messrs Keeling and Shaw.

The Rutland Hotel … Bath Street was widened in front of the hotel

And also, at the end of this period, a memorial was sent to the Lincensing Committee, asking for the licensing of premises to take place at Ilkeston rather than at Heanor, as had been the case until now. These were what were referred to as the ‘Brewster Sessions‘.

And into 1890 mostly via the Borough Surveyor, Henry James Kilford, the council continued its work, examining the drinking premises.

The Derby Arms Inn … The inn was owned by John Trueman (yes, him again !!) though he wasn’t the landlord. The Council now ordered asked him to make the covering to the entrance of the cellar on a level with the pavement.

Great Northern Hotel … Henry James Kilford was asked to explore the advisability of removing the lamp standard outside the Great Northern, situated in Cotmanhay Road

The New Inn … Adkin Toplis was landlord of this beerhouse. It wasn’t the one in middle Bath Street at the corner of Providence Place, but the one opposite the Old Harrow Inn, at the corner of East Street. He asked if he could use the Borough Arms on the painted sign outside the beerhouse, and presumably rename the premises as ‘The Borough Arms’. Permission was granted.

The Brick and Tile Inn … the agent for the Duke of Rutland was approached to quote a price per acre for land at the back (east) of the Inn. It was presently being farmed by Robert Skevington and the Council saw it as a possible site for its new cemetery (see above)

1890-1894; the Temperance Union

Joseph Scattergood led a teetotal lifestyle — very vocally. When the Compensation Clauses in the Local Taxation (Customs and Excise Duties) Bill were being discussed in Parliament in the summer of 1890, Joseph was a leading figure in the local opposition to them. As their name suggests it was proposed that any landlord who wished to leave the liquor trade could seek financial assistance to do so, payable out of County Council public funds.

In late June Joseph chaired a public meeting in the Market Place to voice opposition. Public houses should be closed without compensation !! The sober part of the community had had to pay increased costs of police, prisons, lunatic asylums, workhouses, all because of the drink trade !! They should be compensated, not publicans !! The meeting passed a resolution urging the Government to withdraw these clauses.

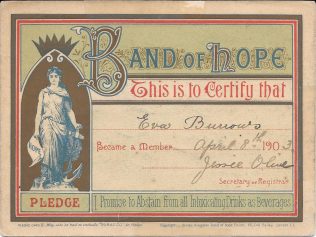

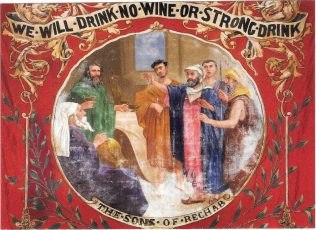

About two weeks later there was a Temperance demonstration in the town, again prominently featuring Joseph, but this time in celebration — of the defeat of the Government’s licensing proposals. A procession was formed, of the Bands of Hope of all the town’s Methodist and Baptist chapels including many children, of Rechabites, and members of the British Women’s Temperance Association, with banners and flags, and led by the Temperance Brass Band, which tramped the main streets. It eventually came to rest in the Market Place where four large railway drays had been formed into a platform for a choir and the main speakers, chief among them Joseph, President of the Ilkeston Band of Hope Union.

In May 1893 a new Temperance Hall and reading room was opened in Bath Street, close to the Wesleyan Chapel there. Made of wood it had cost £100 with an estimated £100 to be spent — the final cost was in fact just over £260. The building had a hall, 20 yards long and about six yards wide, with a small room beneath for the sale of temperance literature. Joseph and his second wife Maria had been the motivating forces behind its establishment. And in the following month it was granted a music licence after a successful examination by the Borough Surveyor.

At that time there were 49 public houses in Ilkeston.

The problem for the Temperance movement was that its new headquarters were within the property bounds of the Wesleyan Chapel which might, at any time, reclaim it for the chapel’s own purposes. Another site which could provide a more permanent home was required. And there was still an outstanding debt to be paid off on the bill for building the recent wooden Hall. Some serious ‘fund-raising’ was required !! What better solution than to call on the Temperance Ladies ?!! On April 25th 1894 their Grand Bazaar was opened.

Present at the opening was an impressive list of local dignitaries… the Mayoress, the vicar of Holy Trinity Church and his wife, Joseph Scattergood and wife (of course), the wife of the Vicar of St. Mary’s, the Woolliscrofts, many Town Councillors … and several ‘out-of-town worthies’. They were there to buy, not to talk, and so the Rev. Binney kept his remarks short as he introduced Mrs Boden of Derby to open the bazaar, Unfortunately she didn’t quite keep to the script and got a little carried away with a speech which was anything but short !!

Held inside the wooden hall, items were ranged along both its sides —an art gallery, a museum, a stereoscope, a gipsy fortune teller, a refreshment stall, a fishpond — and £40 was taken on the first day. It continued into its second day.

Three months after the bazaar and Joseph was back at the Temperance Hall, but this time in the chair of an anti-vaccination meeting. And a few weeks later he was standing in the Market Place addressing a similar meeting, at which a resolution was passed calling upon Ilkeston’s M.P. Sir Walter Foster to support the repeal of the Vaccination Acts.

To some, temperance simply meant moderation, and for them that was not enough … it was either the whole hog or none. Thus, abstinance was what was required. There were so many local examples to prove the point.

For example, on January 12th 1893 William Milnes, a cab owner of South Street, was driving his four-wheel conveyance along Rutland Street at one o’clock in the morning, returning from a local ball, with a police officer on the box beside him. He felt the vehicle going over an obtacle and quickly stopped. The P.C. got down to investigate and discovered labourer John Hadley, lying in the road; as well as being severely injured, he appeared starved and benumbed. Putting him in the cab, they rushed to the cottage hospital but John died shortly afterwards.

At the nearby Durham Ox Inn the same day, the inquest jury returned a verdict of “accidental death” and expressed an opinion that John would have frozen to death if he had not been run over — so, that was alright them !!!

This episode proved to several zealots that ‘excess drinking’ was the real culprit. “The stupifying influence of strong waters” had caused John to collapse in the middle of the road, “and in his soddened state of mind was unable to rise again. There he lay in the fog and frost … thus another drunkard met his death” (The unwritten conclusion seemed to be “and good riddance !!)

At the end of November 1894 a Temperance Sunday was in the calendar, celebrated at several vunues around the town, one of them being, of course, the Temperance Hall. There a talk on ‘Our National Drink Bill’ was given and some startling ‘facts’ revealed.

The average yearly consumption of foreign wine was 15,897,867 gallons, of spirits was 30,520,807 gallons, and of ale and beer was 1,021,630,618 gallons.

For every man, woman and child in the country, this amounted to half a gallon of wine, more than a gallon of spirits and 30 gallons of ale … enough for a canal three yards wide and three yards deep from Land’s End to Scotland. Each of them on average would spend £4 10s on drink, nearly £20 for every family. This was enough to pay off the National Debt in five years.

With that money, 38 golden sovereigns could be placed on every letter in the Bible.

The corn used to make the beer would have fed 11 million people with bread.

An if all the beershops and public houses were laid end to end they would stretch from John o’Groats to Land’s End.

What a waste !! The only duty of a faithful Christian was total abstinence for the individual and prohibition for the nation.

The Brewster Sessions of August 1895

These were held at Heanor, August 19th, before Alderman William Tatham (chairman) and a group of eight other ‘worthies’ including Mayor and Alderman Frederick Beardsley.

Police Superintendent George Daybell gave a report for his division.

There were 108 ale-houses in the area, 70 were ‘tied’ and 38 ‘free’. Seven ale-house keepers had been convicted of an offence during the year, though none of them were now existing Ilkeston landlords.

There were 64 beerhouses, 50 ‘tied’ and 14 ‘free’. Two keepers had been convicted.

There were 74 beer-off licences, 15 of them ‘tied’ and 59 ‘free’.

On average there was one licence for every 221 inhabitants.

In the district 238 persons had been convicted for drunkenness (170 in the previous year) .. this was 4.5 convictions for every 1000 inhabitants.

The Rev. James Herbert Bainton of the Queen St. Baptist Chapel attended the Sessions at the head of a Non-Conformist delegation, appearing there not as a ‘group of teetotallers’ but as ‘Christian men to promote moral and social welfare’.

Bostock’s Bath Street Refreshment House: 1881-1901

At number 8 Bath Street was Herbert Bostock – formerly a coalminer but now a grocer and confectioner. He was the son of lacemaker William and Sarah (nee Henshaw) and in August 1877 had married Harriet Trueman, daughter of Durham Ox landlord John and Ann (nee Cope). His younger brother Owen had married Sarah Trueman, sister of Harriet, in July 1874.

In September 1881 Herbert was granted a licence to sell beer on his Bath Street refreshment house premises – from his father-in-law’s brewery? – provided they were for consumption on the premises. By 1891 the shop had been renumbered as 17.

In August 1895 Herbert was ready the leave the shop and hopefully to take the beer licence with him. He was moving down Bath Street, on the same west side, but now just below the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, to number 59 where he would keep his restaurant/refreshment house to accommodate 100 customers. He thus had to apply to the Court for a transfer of the licence to the new premises, an application which met with the approval of the inhabitants and the tradesmen of that area, who all desired something to eat and drink — or so Herbert claimed. However to back up his claim he had a memorial signed by 438 people who had all used his restaurant in the last six months, as well as an additional memorial signed by 166 of the town’s principal inhabitants including four Aldermen, 16 Councillors, six members of the School Board, the Town Clerk, the Borough Surveyor and the Vicar. (What gives you the impression that Herbert was determined not to fail ??!!)

As it transpired, he need not have worried — there was no opposition and the transfer was granted.

Licence renewal

At the same time and at the same court several other interesting applications were dealt with …

Zillah Wright, 27-year-old spinster, applied for the renewal of her temporary beer-off licence at 82 Awsworth Road; this was at the corner of Awsworth Road and Victoria Street. The licence had been in existence for 17 years, as an off-licence, though not held by Zillah. It had been previously held by Thomas Bostock who was married to Zillah’s aunt Mary (nee Henshaw).

When Zillah’s mother, Zillah (nee Henshaw) had died just a fortnight after her daughter’s birth, the baby was adopted by her aunt Mary and husband. Thomas Bostock died on March 5th, 1888, and the licence then passed to his widow Mary who died on October 24th, 1894. As her adopted daughter, Zillah had helped Mary manage the business and was thus fully acquainted with it. She had also been recently appointed as postmistress at this Awsworth Road branch office, a position of some trust.

All of this was put to the Court in argument — it was not therefore a new licence but really a licence transfer — and the Court had to decide if Zillah was responsible enough to be awarded it. She had a memorial signed by 215 people including several prominent inhabitants of the area. She also stated that this was a free house and she would never tie it to any brewer. Although there was strong opposition from the Ilkeston Temperance Society and the Band of Hope Union, Zillah was granted her licence.

For the rest of her life, Zillah remained a spinster, living in the same premises (then numbered 80 and 81) and died there on October 9th, 1938, aged 70.

Henry West had a beer-off at the corner of Awsworth Road and Cotmanhay Road (number 1 Awsworth Road) and he now applied for a renewal of his temporary licence. He was the husband of Betsy Phipps, married in 1890, and had inherited the licence from his mother-in-law, Sarah Phipps (nee Herring), who had just died, on June 21st, 1895. (Sarah had inherited it from her husband William after he died, April 12th 1890).

To support his application Henry had a memorial signed by 203 people. Judging by the number of its customers, it was a successful and popular business, and was a free house — Henry promised to keep it as such.

However once more there was opposition from the Temperance Society and the Band of Hope … and more !! Joseph Kirk, landlord of the Derby Arms and John Stubbs of the Commercial Inn, both tied houses and both very close to Henry’s shop, opposed the application … and brought maps to show how they would be adversely affected. However Henry was granted his licence, though the Court’s decision was not unanimous.

Almost immediately, having secured the valuable licence, Henry put the freehold shop and house up for sale, and at the same auction he offered his three houses in Bloomsgrove Road for sale.

Reuben Limb was a member of the Town Council and had inherited a licence for a beer-off at 177 Cotmanhay Road from his uncle Enoch Limb when the latter had retired. Enoch had had the licence for 18 years and now Reuben applied for a renewal. He now owned the premises and could keep it as a free house. And of course his position enabled him to claim that he was a ‘man of high character’ and had a memorial signed by 576 persons to prove it, eleven of them being fellow Town Councillors.

Again the opposition failed and Reueben got his renewal.

Thomas Bostock and his family lived at 35 Rutland Street in a property which he had built himself 21 years before. He had originally let the premises to tailor Joseph Bailey and got him a licence in about 1877. In October 1894 Joseph and his wife Alice (nee Appleton) left Ilkeston for Gotham village in Nottinghamshire and Thomas moved into the shop. The licence was transferred to him and now he was applying for a renewal.

As usual a memorial was offered, this time with 412 signatures, a free house was promised, and opposition was put forward … and a licence was renewed.

As his name suggests, Abraham Campbell Mitchell was a grandson of Abraham Mitchell and Ann Campbell (who were married on April 4th 1830). By 1895 he was trading at an off-licence at 37 Market Street, a premises which had been licensed for 15 years. In about 1885 it was acquired by the Carrington Brewery Company who allowed the previous occupants to remain there. They were house painter William Robinson and his wife Sarah Ann (nee Pollard) and children, but by 1895, because of William’s failing health they had decided to leave.

In 1895 Abraham took over and applied for a licence renewal. He presented his memorial with 389 persons signing it. His application was refused !!! (Did you spot the difference ??)

Abraham decided to appeal.

Still at the off-licence, Abraham died on July 31st, 1897 and his widow Mary (nee Cockayne) took over the licence in September of that year.

In 1895 the premises at 51 Belper Street belonged to Ezekiel Severn who had owned a beer-off licence for the property for 15 years. At the age of 61 in 1890, he had married, for the first time, to widow Ann Wright (nee Tipper) and had decided to retire from the grocery trade. The premises were then let to Tadcaster Brewery Company and its tenant was Willie Fletcher who now had to apply for a renewal of the licence. (Willie was a son of the late Wood Street lacemaker Samuel Fletcher and a younger brother of the ‘notorious’ Tom Walter Fletcher)

Willie presented his petition with 192 signatures but the members of the licensing board were evenly split on this application and adjourned their decision for a month.

William Hardy had acquired a licence for the beer-off at 29 Norman Street when it was transferred to him from the previous tenant, Edward Hatter, who became bankrupt. Edward’s father, John Hatter, had been the owner of the premises which were leased to Stretton’s the brewers. William’s memorial convinced the authorities who granted the licence.

The Station Road problem and the Peacock Inn.

In the early 1890s there was much interest in developing a licensed premises at the bottom of Station Road, both by the Town Council and by private individuals. All had been rebuffed by the authorities however.

In December 1893, William Beer replaced William Holmes as landlord of the Old Harrow Inn. And it was William Beer who applied for a transfer of a provisional full licence in August 1894. At that time the Old Harrow was still the property of Ilkeston Corporation but William wanted the licence for a new Inn which he hoped was going to be built in Station Road on land also owned by the Corporation. William’s application was supported by the Town Council (which was struggling with the problem of the Harrow Inn Corner), but it had outspoken opposition. The latter came in the form of the Temperance ‘party’ and the trustees of the Wesleyan chapel in Station Road, which had opened less than a year before, at the corner of Rupert Street. And there was also opposition from Sarah Ann Shaw, widow of Reuben, and her son-in-law James Cooke (married to Georgina Shaw) who had property interests in the Station Road area and who wished to develop their own licensed premises there … this was on the north side of Station Road, between Canal Street and the Erewash Canal. The premises had already been built and all they needed was a licence for it to operate as an ‘inn’ … it went by the name of ‘The Sea View’ and had cellars and kitchens in the basement, a smoke room, bar parlour, tap-room, club room and six bedrooms in the other storeys, and stabling for six horses. (The property is described in more detail here). Their application was supported by testimonials from the vicar of Holy Trinity Church (the Rev Binney), Edwin Trueman and a memorial signed by 324 local inhabitants. The area was growing rapidly and the last six years had seen over 200 houses built there with more being built close by. There was no full-licensed house within the whole of Station Road which numbered 155 premises, while adjoining streets brought that number up to 805.

In competition to the Shaw-Cooke application, William Beer’s application was for an adjoining property.

In time-honoured fashion, the Licensing authority expressed the opinion that no new licence was needed and therefore would not be granted. James Cooke’s application was thus rejected. And so too was William Beer’s request of a licence transfer for the Old Harrow Inn.

In August 1895, to continue the story of Station Road development, up stepped John William Shaw, landlord of the (remote ?) Peacock Inn in Church Street, Cotmanhay. He wished to transfer the Inn’s licence to a site down Station Road where he hoped to establish a new inn. The Peacock was an old, long, low building and had suffered from the consequences of mining operations underneath it; it was hardly safe at the present moment. It was dangerous as it was, and yet could not be altered or extended until the ground had settled.

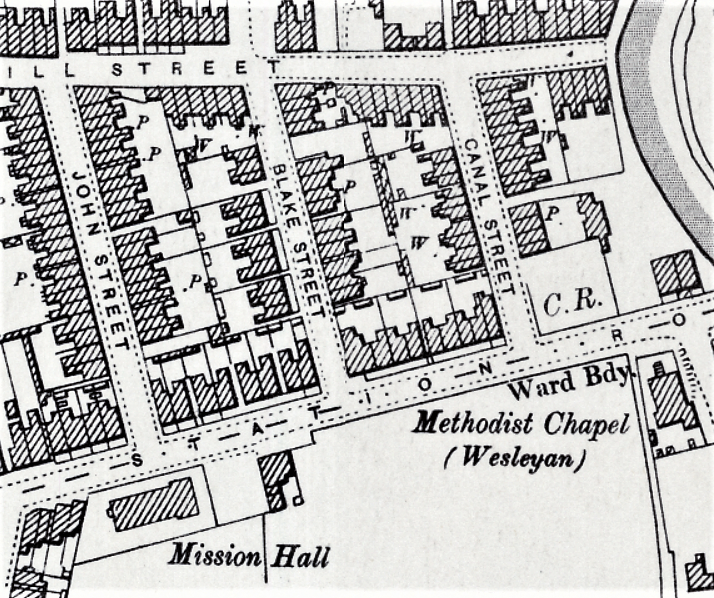

It was stressed by those supporting the application, that this was not a new licence and as such, it should not be argued that it was increasing the opportunities for drunkenness in the town — an argument often put forward by those supporting temperance. This was a case of shifting a licence from a thinly populated district (but supplied by two or three other ‘houses’) where it was doing no good, to one where it was wanted. Station Road was populous and increasing, with many new houses, yet with few licensed premises. The new inn would be opposite the block of houses between John Street and Blake Street on ground belonging to the Duke of Rutland (at what is today the corner of Alvenor Street with Station Road), and would be suitable for commercial travellers.

Witnesses were called to support John William. Joseph Duro Baker, the town’s assistant surveyor, was there to testify that there were 699 houses in this catchment area, ready to be served by a new inn — and soon there would be more. Councillor, architect and surveyor George Haslam had brought along his plans for the new building costing an estimated £1500. And John William himself testified that his present Peacock Inn, which belonged to the Duke of Rutland but was leased to the brewers, Messrs. Shipstone, served only about 26 houses.

But as usual, there was opposition. Memorials were offered, one signed by 294 Station Road residents, and another by 37 property owners, objecting to the new licence in their area. The Rev. Bainton spoke for ‘the town’s Nonconformists’ when he said that where the Peacock Inn was at present situated did little harm — though it did no good either !! — but in Station Road it would be a mighty force to extend the drink traffic and drink curse in Ilkeston. To him it was the job of the magistrates to reduce the number of licences whenever they could. He was backed up by a petition signed by 235 Sunday School teachers, representing 3500 scholars.

The hearing would have continued at some length except that the Chairman, Alderman William Tatham, cut it short. They had heard enough. Once more a licence for the area was refused.

The Temperance Eating House in Bath Street.

This was situated between Brussels Terrace and Stamford Street — at 140 Bath Street (four doors north of Stamford Street) — and in 1896 was owned by George Hall.

In April of that year he applied for a music and dancing licence for the premises, and everything seemed to be advancing very smoothly as he put his application before the magistrates. George said the licence would be for an upstairs room, on the first floor; it had been approved by the police, after an inspection when no problems had appeared — it was a fit and proper room for dancing. Classes would be limited to a certain number, no refreshments would be served … and of course, no alcohol !!

But naturally there had to be a ‘fly’ in the ointment … this time, in the shape of music dealer Robert Robinson whose shop and living premises were next door, at number 142. He had been disturbed by incessant stamping of dancing feet such that his music lessons were almost impossible to conduct. His wife had had to move out on occasions because of the noise. And then draper John Glassey at number 138 felt he had to share his experiences too. His shop business was also being disturbed, while his sitting room next door to the dancing classroom was no longer a place of rest and quiet.

The magistrates were sympathetic to the neighbours and refused George’s dancing licence. But what about the music licence ?

Well, Robert had something to say about that too. On one past occasion a brass band with a big drum had occupied the room — the noise was deafening !! At another time the “Kentucky Midgets”, who were performing at the Theatre Royal, held a rehearsal there; Robert had no objection to a piano or even a string band, but he drew the line at wind instruments !! He himself never allowed their use in a small room.

On this issue however George found more success. The magistrates allowed a temporary licence — George would have to apply again in a couple of months time when the licence would be reassessed.

I’m not sure if George Hall got his licence but I am sure that by June of the following year he had sold up and left Ilkeston. On June 17th 1897 his shop and dwelling house were auctioned off at the Mundy Arms. It had an unexpired lease period of 86 years and an annual ground rent of £6 15s; it was purchased for £800 by Nottingham draper Clement F James.

(to be continued)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

And now we are ready to walk up Heanor Road and then into Cotmanhay, perhaps to catch a glimpse of some of these more remote pubs and beer-offs ?