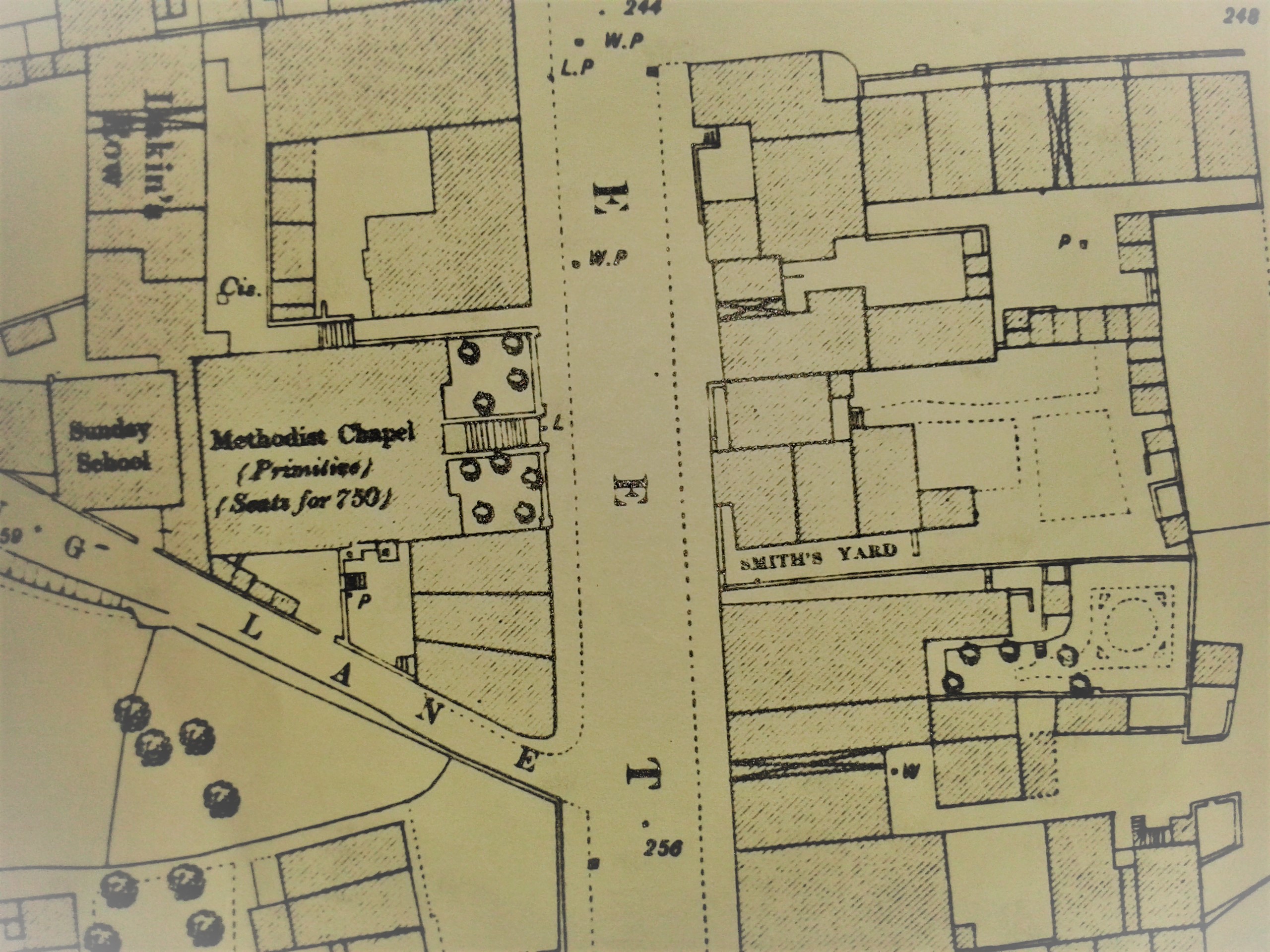

Adeline Wells describes this part of Bath Street being “above (on the south side of) Chapel Street (and just above the Prince of Wales beerhouse). It was Smith’s Yard, with two or three cottages in it.

Mr. Smith had a small shoe shop against his double-fronted, white washed cottage, standing back, with low wall in front.

He had three sons, George, Henry and Edward, and one daughter, Sarah. (Adeline refers to her also as Hannah) She married Aaron Aldred, a machinist, at Carrier’s and the brother of Isaac Aldred, of Jack Lee’s Yard”.

We are now almost opposite the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Bath Street.

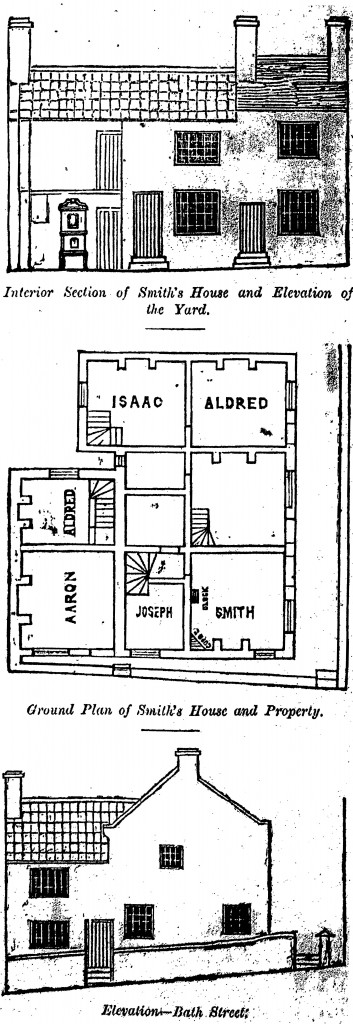

Views of the Property of Joseph Smith. (IP August 1861)

These were taken from drawings made by South Street joiner and builder William Warner for reference at the trial.

Shortly after nine o’clock on Monday morning, July 29th 1861, George Clay Smith, eldest son of Joseph and Harriett (nee Clay), found himself standing in the dock at Derby Assizes, facing a packed courtroom. There he was accused of wilfully murdering his father at Ilkeston, on May 2nd, 1861 and pleaded ‘not guilty’.

He was a young man, 20 years old, 5ft 5ins tall, with reddish yellow hair and pleasing features. On this occasion he was neatly dressed, including a blue scarf and turn-down collar.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The case for the prosecution

1] Joseph Smith — alias ‘Red Smith’ — had been a cordwainer, living in Bath Street with his three sons, George, Henry and Edward, in the first of ‘a neat little row of four cottages’ which he owned. He was described as a steady, industrious tradesman with frugal habits who had managed to accumulate savings of about £150 which he held at Nottingham Savings Bank. However he had the reputation of being ‘an indulgent parent’.

2] Samuel Smith, shoemaker of Chapel Street and brother of Joseph, was called as a witness.

Samuel lived a short distance from his brother and had had an evening visit from him very shortly before his death. Samuel had later found his brother dead in his own home.

3] Then Henry Smith, younger brother of George, was called to give evidence, clearly affected by the proceedings. He gave his age as 16 until George shouted correctly from the dock that he was 17.

Henry shared a bed with his father, while George shared another bed in a separate room with the youngest brother Edward, who was very nearly 13.

On the evening of May 1st Henry, who helped in his father’s trade, had finished working at 7.30p.m. and was in the house with his father. The pair had then gone out together, had separated, and when Henry returned home at about 10.20 pm, his father was already there, with Edward joining them shortly afterwards. George was not about the house and so the three of them eventually went to bed although Joseph later went downstairs.

Shortly after, Henry went downstairs to find his father looking through a drawer, obviously searching for some thing. He spoke awhile with his father and then returned upstairs, alone.

At this point, as the bedroom door was open, Henry heard George come home and heard his father ask ‘George, have you been to Nottingham today?’ He heard more conversation and then what sounded like a pistol shot. This must have startled Edward who came into Henry’s bedroom and both shouted ‘Murder !’ from the window. The cries alerted their married sister, Sarah Aldred, who lived in another part of the building and who came to the dwelling. The three of them found Joseph dead, and when George came into the house a little later Henry accused him of killing their father.

George replied “I have not, my lad”.

The court then heard evidence from Henry about his father’s temper and drinking habits along with his depression and threats to commit suicide.

(Joseph’s first wife Harriett Clay had died in a typhus outbreak of 1854 and he had remarried in 1857. This marriage had lasted 22 weeks of which only the last two weeks were spent together; Joseph’s second wife accused him of assaulting her in a drunken rage, of pulling her hair, kicking and threatening her. Although Joseph claimed he had received similar treatment from her, the court chose to believe the wife and Joseph was bound over. Needless to say the happy couple spent no more time together.)

4] Edward Smith was then called, giving his age as 13. (He was born on August 6th, 1848 and registered as Edwin). The lad was visibly upset and talked of finding an amount of pistol shot wrapped in paper in the family’s pigsty, three weeks after Joseph’s death.

5] Sarah Aldred, wife of lacemaker Aaron and elder sister of the three Smith brothers, next gave evidence and confirmed much of what had already been said, adding that she had found her dead father at half past 12 of that night. She spoke of her father being depressed after his second wife had left, and how he had threatened to take his own life and to harm his family too.

6] Isaac Aldred lived in another part of the same set of houses and was brother-in-law to Sarah. He too had been drawn to the house by cries of ‘Murder’ and had seen Joseph, lying on the hearth, with his brains on the floor, shot in the left side of the head. When George then returned to the house, Isaac had also accused him of the killing but George denied this and claimed that his father had shot himself. When Isaac pointed out that there was no sign of a pistol, George said that his father must have got rid of it ! This clearly puzzled Isaac. George was confused and not thinking clearly — or clearly not thinking!

7] The police then arrived and arrested George but before being taken away he was ready to clarify his confused account. He admitted that he had taken the pistol from the hob where his father had laid it and thrown it into a garden nearby.

He knelt at his father’s side and said “I love my father, although he shot himself”.

8] Aaron Aldred gave evidence that he saw George in the lock-up on the next day, when George was still denying the murder and repeating his claim that his father had committed suicide.

“The police then arrived and arrested George” (Illustration printed by W S Fortey, Monmouth Court, Seven Dials)

9] Police Superintendent John Hudson confirmed that George had stressed his innocence when charged with the murder. The accused had claimed that he had just returned from Nottingham, had argued with his father, who then picked up the pistol and shot himself in the head. George picked the gun up and then ran to fetch his friend, Reuben Davis, throwing the weapon into what George thought was Stocks’ garden as he ran. The police had soon found it, close to where George said it would be, with no bloodstains on it.

(John Stocks was a hosier who lived close to the Smiths’ home, in Lee’s Yard, later Albion Place).

10] Doctor George Blake Norman attended and examined the dead man. Joseph had died as a result of a shot, above and a little behind the left ear from close range. In the doctor’s opinion it could not have been fired by Joseph’s right hand and only with difficulty by the left hand. The trajectory of the shot suggested it had been fired by another person standing higher than the deceased, although he admitted that it was not always easy to determine this as the shot could have been deflected. A second doctor, Nathaniel Best Gill, stated that it was just possible that Joseph could have inflicted the wound upon himself.

(Joseph was right-handed. “There never was a left-handed shoemaker; such a man could not make a shoe” according to his brother Samuel.)

11] Henry Davis was a friend of George and had been with him during the day prior to the death of Joseph. According to Henry, George had talked about his father becoming very agitated, depressed and making a will. They had then gone to Nottingham, visited the Savings’ Bank there, although Henry had stayed outside while George conducted business within. The latter had his father’s bank book which he left at the Black Bull spirits vault in Long Row, as his father had told him, and then the two went on to the Tom Moodie public house where they met a girl called Elizabeth Meakin. George spent some time with her and away from Henry before the two men left Nottingham and returned, by train, to Ilkeston. At the Ilkeston Junction station George got off at about half past seven while Henry went on to the Town station, and later saw George with Reuben Davis, Henry’s brother.

12] According to John Stevenson, a clerk at the Nottingham Savings’ Bank, George had gone there with his father’s bank book to withdraw some money but this had been refused because he did not have the written permission of his father.

13] John Bridger, who had many Ilkeston friends but didn’t know the deceased Joseph Smith, was the keeper of the Golden Ball wine vaults in Long Row, Nottingham. He told of how George had brought his father’s bank book to his vaults and had borrowed a sovereign, leaving the book as security. The next day, May 2nd, George’s younger brother Henry had visited the vaults, paid a sovereign and reclaimed the book. (Henry had confirmed this in his own testimony).

14] Daniel Webster, a general dealer in Clumber Street, spoke of how George had purchased a pistol at his shop while Eliza Carr, wife of ironmonger James, dealing in the same area, recalled selling George some caps and powder for the pistol, which he had shown her at her shop.

15] Elizabeth Meakin, ‘a woman of disreputable pursuits’, confirmed that she had met George in the Tom Moodie public house, spent some time with him at her lodgings, during which he had shown her the pistol and even fired off a cap, but told her that he did not wish his mate to know about it. George had added that he was going to be married and that there were two girls who had had children by him. She recalled George saying “I shall do no harm to them who do not harm me, but if my own father offended me I would shoot him”.

16] Reuben Davis and George worked together on the same machine at Messrs Ball and Sons, lace manufacturers of Albion Place, and lived very close to each other in Ilkeston. Reuben admitted meeting George on his return from Nottingham and the two of them had gone to the shop of James Chadwick, grocer and ironmonger, in Bath Street, where Reuben bought some shot and caps. He explained to George that he wanted these articles to kill some wood pigeons next morning. The two men then eventually ended up at the Queen’s Head in Bath Street but it wasn’t long before George left, only to return about a quarter of an hour later. He told Reuben that he had been home and found his father in a distressed state, upset with George’s wild ways, and threatening to end his own life. “I do not think my father will live long; my opinion is that he will do away with himself”, he told Reuben.

(The prosecution challenged this last point. Why should Joseph ask his son whether he had been to Nottingham, as brother Henry had stated earlier, if the father had already seen George and spoken to him earlier in the evening?).

Reuben claimed that he had left George at the Queen’s Head at about 11.40pm, had returned home to bed but was soon disturbed by George, knocking at his door, claiming that his father had shot himself. As the two were going back to George’s house, George reminded Reuben of what he had said earlier in the evening.

17] Martha Cockayne, 12-year-old daughter of William and Mary (nee Henshaw) and a neighbour of George, had met him about half past eight on that night — when he was on his way back to the Queen’s Head — and he had sent her to Isaac Gregory’s shop, close by, to buy a pennyworth of pigeon shot No 2, and this was confirmed by Isaac Gregory.

George rewarded Martha with a counterfeit halfpenny!

18] Next we hear from Sophia Meakin, 33-year-old dressmaker of East Street, and her niece Harriet Robinson, aged 13, who lived with her aunt and grandfather. Sophia stated that the two of them had been walking up Bath Street at half past 12 at night, carrying some recently washed clothing, while Harriet was also holding a candle. As they passed John Beardsley’s house, a few yards from where the Smith family lived, they saw George who turned away from them. He seemed to be trying to hide something which he held in his hand and quickly walked on to his house. Shortly after this they heard a commotion at the house and loud screaming. Harriet had clearly seen George by the light of her candle and she confirmed what Sophia had said. She too had heard the noise but it was only until the next day that she heard about the death.

19] Caleb Mountney, turnkey in Derby jail, seems to have been listening in to conversations between George and his brother Henry and brother-in-law Aaron Aldred when George was in custody. Thus on June 19th Caleb heard them talking about something in their pigsty, while Henry told George that brother Edward had found it.

20] The final witness for the prosecution was Elijah Ellis, lacemaker, who worked next to George at Balls’ factory. On Tuesday, April 30th, George had asked him about his father dying without making a will, and Elijah had confirmed that George would not inherit any property until he came of age — that is, reached 21 — and nor could he chase his father’s debtors until that time. George spoke of his intention to marry Ellen Cox, who was in the family way by him, at Whitsuntide, and expected to come into money quite soon. This testimony was disputed by George who stated that he was not at work that day.

(George was born on April 16th 1841 although the 1841 census records him as two years old… it should be two months old)

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

The case for the defence

The following points were made:-

A] George had not lied about the bank book at the Savings Bank but had been quite open about his affairs there.

B] As George kept pigeons, there was nothing unusual in him buying a pistol and some pigeon shot ‘to start pigeons, to see which would fly the fastest’, as he had claimed when he bought it.

C] He had left the pistol in a drawer at home and his father had discovered it that night, when he was in an agitated and disturbed state of mind.

D] Several people close to Joseph had spoken of how depressed he had been lately, making threats to take his own life.

E] Throwing the pistol away was an impulsive action. If George had planned a sly and crafty murder as had been suggested, would he not have placed the pistol in the hand of his father to support the idea of suicide?

F] No blood was found on the hands of George when Dr. Norman said that the hand that fired the gun would most probably have been bloodied.

G] While many of the points might support the conclusion that George had killed his father, they might just as well confirm that Joseph had committed suicide. Consequently the son should be given the benefit of the doubt, as the evidence was consistent with his innocence.

Not a single witness was called in his defence.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The verdict and sentence

After the judge had summed up the evidence, the jury deliberated for only a few minutes before George was found guilty. The judge then donned his black cap and began to pass sentence at which point George interrupted and was allowed to continue..

“…..I have not taken the life of my father. I stand here with innocence and I can stand before the Almighty Maker of heaven and earth with a clear conscience. And if I come to die upon the gallows tree I will still say that I am innocent….But, my Lord, if you think I have done this crime, pass sentence on me……

(then speaking to the people in the galleries) ” I speak like an English son and like an English brave man; I want nothing but my rights. I would scorn to kill my own dear and beloved father. Could I stand here accused of this crime and speak to you this way if I was guilty? Could I raise my right hand as I do now, if it was stained with my father’s blood?…..Gentlemen, friends and fellow countrymen – Not that this right hand of mine has been stained in the blood of my father; far from it”.

The judge was not impressed by George’s words, considering they were those of a sinful, deceitful and unrepentant man. His conclusion was therefore unavoidable.

“The sentence of the court is that you be taken from the place in which you now stand to the place from whence you came, and from thence to a place of execution, and that there you be hanged by the neck until your body be dead, and that your body, when dead, be buried within the precincts of the jail where you shall have last been confined”.

(At the coroner’s inquest into Joseph Smith’s death, on the days immediately after his murder and three months before the trial, the coroner was clearly convinced that George had committed premeditated murder and conveyed this to the jury. The conclusion there was that the cordwainer had died as a result of “being shot by his son” and a verdict of ‘Wilful Murder’ was returned. Thereupon George was committed on the Coroner’s warrant to be tried at the Derbyshire Assizes. And thus the Nottinghamshire Guardian felt free to report an extensive account of how ‘the wicked wretch’ George had murdered his father, again nearly three months before his trial).

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Confession and punishment

Shortly after he had been returned to the county jail in Vernon Street, Derby, George made a full confession.

Events had occurred as the prosecution evidence had suggested although the motive was not one of greed, nor had the murder been long in the planning. He had bought the pistol with the intention of killing his father if he started questioning him about the bank book, and had returned from Nottingham with murder on his mind. The pistol was primed. However after further drink and a game of bagatelle at the Queen’s Head these thoughts vanished, and George finally went home, still vexed but wanting to sleep. An argument soon developed however. George became angry with his father who, in turn, was annoyed with him and banished him from home, at which point an intoxicated George took the pistol from the drawer and shot his father.

George was now fully repentant. He was visited regularly in prison by the Rev. Ebenezer Sloane Heron of the Ilkeston Independent Chapel, although George’s background was with the Methodist chapels in Ilkeston where he had recently attended services.

Other visitors included his sister, brothers and Ellen Cox, a lass from Belton whom he had intended to marry. Many tears were shed.

George had a less cordial meeting with his uncle Samuel who volunteered to hang George himself if no-one else was available.

He wrote several long letters to his Primitive Methodist Sunday School teacher, Mr. Samuel Shaw, asking him to warn his scholars against ‘drink, Sabbath breaking, smoking, going to dancings, playing at dominoes, and keeping pigeons’ all of which would keep them from school on a Sabbath day.

His work friend at Balls’ factory, Emanuel ‘Man’ Barker of Awsworth Road, also received word from George; he now thought kindly of Henry and Reuben Davis though they had spoken against him at his trial; he sent best wishes and advice to his friends, Richard Booth, Mark Wheatley, Gervase West, Thomas Ironmonger, George Rigley, John Riley of Stanton, and all his work-mates.

He sent best respects to Emma Eyre of Awsworth Road who had recently given birth to her daughter, whose father she claimed was George and whom George was never to see. This child was Annie Eyre, born on April 25th 1861.

Since being in prison George had put on a stone in weight, had had no drink and tobacco, and had never been in better health in his life!

George did not neglect his relatives. He wrote kindly to his sister Sarah, to his brothers, thanked his uncle Henry Clay, innkeeper at the Mundy Arms, for his kindness, and said goodbye to his aunt Ruth Steer of New Street, sister of Henry Clay, although he rather indelicately reminded her that ‘you will not be long before you are numbered with the dead’. (She was then 52 years old and died of liver and kidney disease in 1866).

At this point the Pioneer felt driven to assess George’s character:

“ There was in Smith the elements of a fine character, such as his strength of nerve, bold daring, self-control, ability to carry out his design, fluency of speech, and a mind capable of much labour, and with cultivation would have enabled him to excel in anything he chose to undertake: but he was frivolous, false, and given to change, awfully licentious, self-indulgent in the extreme; thus his fine faculties were shut up in a prison of steel – the animal was indulged at the expense of the intellect”. (August 22nd 1861)

This is a poem said to be written by George as he awaited his execution.

You feeling Christian pray attend, And listen unto me,

While unto you I will unfold, This dreadful tragedy;

Committed by a guilty one, As you shall quickly hear,

Upon his father at Ilkeston, Well known in Derbyshire.

CHORUS

Oh! The dreadful deed was done. A father murdered by a son.

I hope you will a warning take, By what I now relate,

And think on my untimely end, For wreathed is my fate;

I might have lived in happiness, As you shall quickly hear,

All with my aged father, At Ilkeston in Derbyshire.

Sure Satan must have temped me, Upon that fatal day,

My kind and tender Father, To take his life away;

All with a deadly weapon, It was full intent,

I gave him not the shortest time, On earth for to repent.

I was confined in Derby gaol, My trial to await,

For the awful crime of murder, My sufferings were so great.

The jury found me guilty, And I am condemned to die,

And awful death of public scorn, Upon the gallows high.

The black cap being in readiness, When I was tried and cast,

The learned judge with solemn voice, The awful sentence passed;

You must prepare to meet your God, We can no mercy show

So pray for mercy from above, For none is here below.

I dread to think upon the hour, All on that fatal morn,

When I must ascend the scaffold high, To die a death of scorn,

To the fatal spot thousands will come, That dreadful sight to see,

George Smith to end his days, Upon the gallows tree.

I have brought disgrace upon myself, My friends and family,

No one I’m sure with sympathize Or soothe my misery.

I must prepare to meet my God, I hear the solemn knell,

My time is come I must away, Farewell, a last farewell.

As his final day approached George immersed himself further and further into the Bible, reading texts carefully and praying often. On Thursday evening, August 15th, he spoke with the chaplain of the prison and then with the Rev Mr. Heron for two hours. At 11 o’clock he went to bed, quickly fell asleep and remained so until nearly 4 o’clock the next morning, at which time he was awakened. More prayers and Bible reading followed for several hours.

On Friday afternoon, August 16th, 1861, George was hanged in front of Derby jail before an estimated crowd of 20,000 to 50,000 persons — depending on the source — several of the spectators making the journey from Ilkeston to witness the execution. It was a hot day and many women and children fainted in the crush of the crowd.

In the morning George had sung and prayed in the prison church. On his way to the scaffold he conversed with several of his fellow prisoners and with some of the prison staff, seeming calm and composed, many in the crowd showing more emotion than George. He spoke a short prayer and at ten minutes past noon he was executed.

After being taken down, his body was buried in quick lime within the precincts of the jail.

“An excellent cast was taken of Smith’s head by Mr. Barton, sculptor, of Derby”. .. .. apparently this cast was later in the possession of Nelson Bestwick, stationer and newsagent of the Market Place, Ilkeston. After Nelson’s death in 1981 the cast was destroyed, the remnants disposed of.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————