The Noble Church before 1842

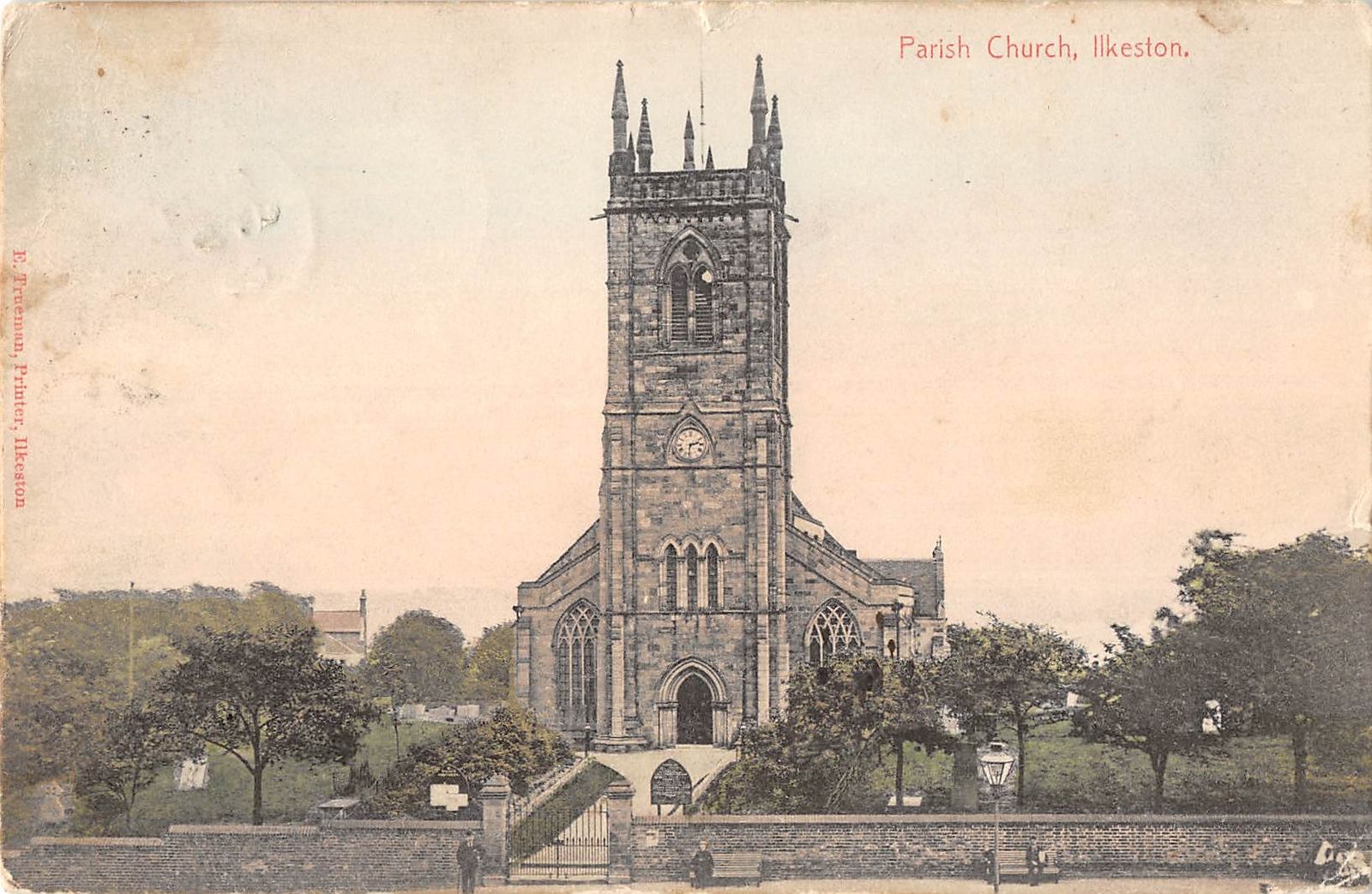

Adeline describes her feelings towards the Parish Church: “The noble church of St. Mary, which is a landmark for the surrounding country, has always been with us and we are proud in being able to call it ‘Our Church’”.

In 1830 at least one other writer was impressed by some aspects of the church. In the Nottingham Review (July 9th, 1830) we find that “Ilkeston Church is known to have an imposing exterior; situated on an eminence, it may be seen for many miles round, and its peal of bells and choir of singers are noted throughout the county. We were rather astonished, we must confess, at the inside view; at the back of the pulpit, behind the head of the preacher, there is rudely carved — “O HEARE THE WORD OF THE LORD. ANNO DOMINI 1634” — thus attesting the venerable rostrum to be nearly 200 years old. The King’s Arms is surmounted by C.II, coevel with the date of about 1670, and at the foot of the board containing the Lord’s Prayer, the following names are inscribed: — Matthew Byrch, Vicar; John Lees, Joseph Wood, churchwardens; Nathaniel Haslewood, Richard Dovey, painters, Nottingham. The latter brace of worthies have contrived to have their names kept in remembrance, after balmost every other record of them has perished”

Edgar Waterhouse then sets the scene of St. Mary’s church in the 1830’s … and it is far from ‘noble‘

“the church was in a badly dilapidated condition. The east window and part of the chancel roof had fallen in, the chantry stood exposed to the sky, the whole of what had been so lovely a thing stood in danger of total collapse. Ilkeston must have been a place fair to the eye in those days but its hill seemed destined to be crowned with a ruin”.

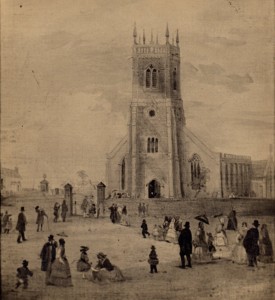

An east end view of St. Mary’s Church in 1840. (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library).

And this delapidation wasn’t a recent deterioration … the church had had its steeple blown down in 1714 and never been rebuilt. Edgar tells us that in 1742 the church was partly unroofed and in 1757 there was a bill to purchase wood to support the said roof, at a cost of £1 4s. It was to cost much, much more than that for a complete refurbishment, as we shall see.

1830s: The Vestry meets to discuss the church condition

In 1835 Ilkeston had an estimated population of 4500 while its parish church would only hold 500 of them, and had not a single free sitting. And at the beginning of 1836 a Vestry was held where the churchwarden, Thomas Cheetham, explained that £150 was needed for repair of the pews, etc,. which would grow to £190 when other vital costs were added.

The Vestry was a group of local ‘bigwigs’, who had acquired powers mainly through custom — it became a group of the more powerful village officials, made up of important owners of property and land, and called the ‘Vestry’ because it originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the church. These people had no choice — they had to serve in their office; it was compulsory. And in return they had power within the community over its income and expenditure. The officers were the churchwardens, highway surveyors, the parish constable, overseer of the poor, and the parish clerk, sextons and scavengers.

A churchwarden was elected for one year’s duty which included various church responsibilities, and with a right to levy a ‘church rate’ if allowed by the vestry. And he had to keep accounts of all the money received and spent.

By the Easter week of 1837 it was time for another election of the churchwarden. It should be remembered that there was no secret voting and that some of the more infleuncial townsfolk had more than one vote, because of their position.

Thomas Cheetham, nominated by Matthew Hobson, was one candidate — he stood as the ‘Radical Dissenter’ candidate, representing the non-conformist interests (Their several chapels in Ilkeston were expected to contribute to St. Mary’s expenses as well as their own). The Church party, headed by George Blake Norman, nominated Samuel Potter to stand against Thomas. At the end of March and into April a poll was taken, and after a scrutiny of the votes supervised by chairman Moses Mason, the result was a win for Thomas by one vote !! 355 to 354.

But this is where the trouble started. Several of those voting were ineligible as they weren’t ratepayers, while some were entitled to more than one vote, a fact which hadn’t been recognised. When these ‘faults’ were corrected the result was very different — Samuel collected 367 votes to Thomas’s 340 — and so the former was duly elected. This was a defeat for the Dissenters of course, who had spent money on “treating the electors“.

At least this was the situation as reported in the Nottingham Journal. Letter writers to both the Nottingham Review and the Nottingham and Newark Mercury had a different story to tell, with a different result, questioning the Journal and reporting a win for Thomas by 10 votes. This was followed by a constant stream of recriminatory letters between these newspapers, not affecting the outcome — which appears to have been that Thomas was reappointed churchwarden.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

George Searl Ebsworth

Adeline points out that “there was a succession of curates, Revs. Moxon, J. H. Green, Jowett, etc.”

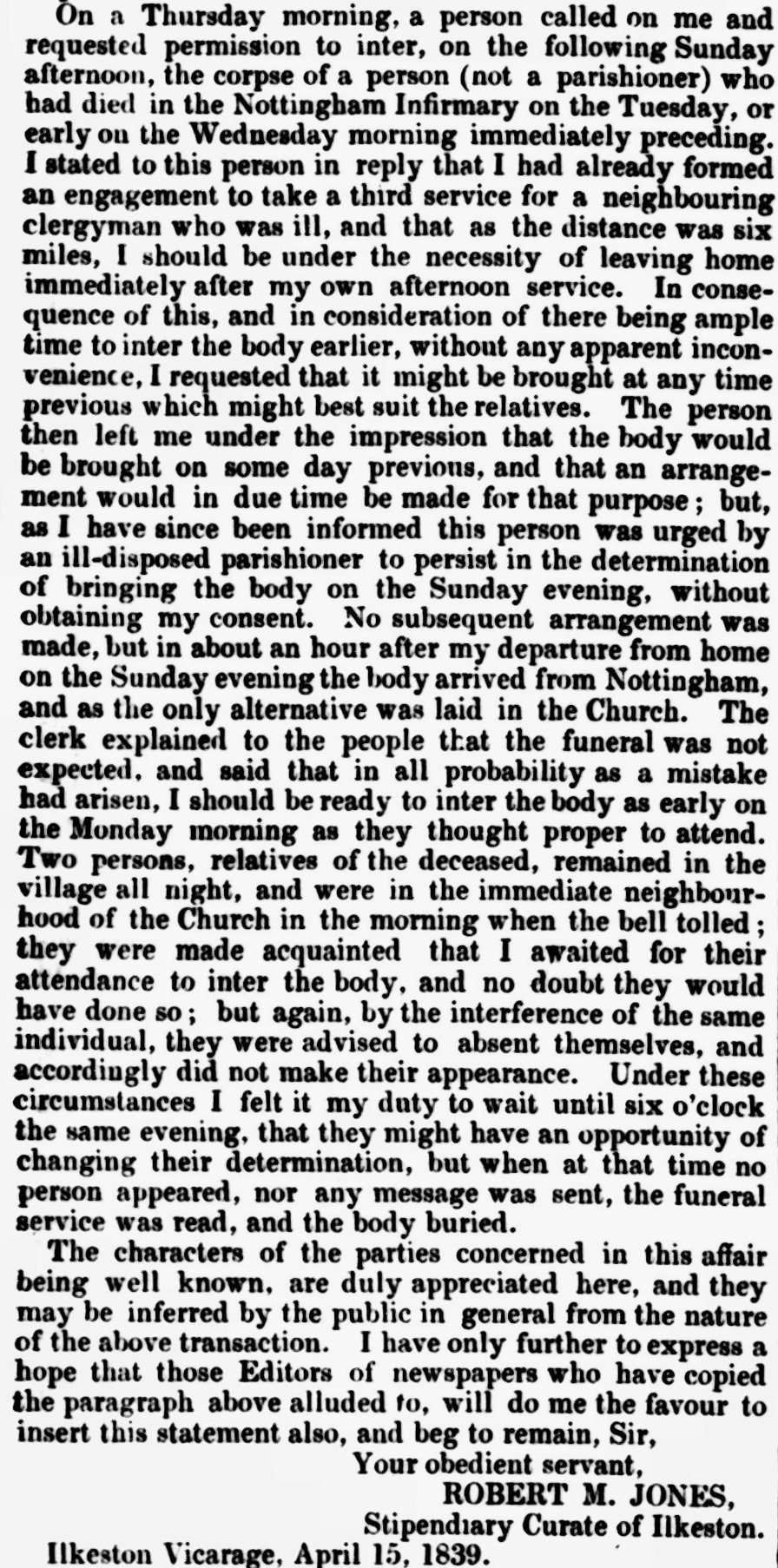

The Curate, Richard Moxon, had died on April 1st, 1836 and his place was taken by the Rev. Robert M. Jones who, three years later found himself being attacked in certain parts of the local press for his behaviour towards a grieving family who wished to bury their relative in the parish churchyard.

Robert felt so anxious to ‘set the record straight’ that he also wrote a letter to the local press (right), outlining what, in his view, had really happened. It appeared in the Nottingham and Newark Mercury (April 19th, 1839)

It would appear from burial records that the body mentioned in the article was that of Mary Paxton (nee Bramley), aged 24, the wife of Samuel, who had died in Nottingham and was buried on March 18th.

1842: George Searl Ebsworth arrives

Although a member of the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, Adeline points out that “our Vicar was Canon Searl Ebsworth. He was well liked by his parishioners, also by many of the Nonconformists. He was a great worker and it was through his instrumentality that the church of St. Mary is what it is today”.

Following the death of the Rev. Jervase Brown, George Searl Ebsworth (M.A. of Clare Hall, Cambridge) was vicar of St. Mary’s Church from 1842 to 1863.

He was born on Christmas Day 1814, in Bethnal Green, London, the son of Thomas and Mary Susanna (nee Crook).

On July 5th 1843 George was married to Sarah Mary Anne Cazalet, daughter of Peter Clement Cazalet and Olympia (nee Cazalet), at St. Nicholas Church in Brighton.

When he arrived at St. Mary’s Church, following posts at Hoxton in Middlesex and then Brighton, shortly before his marriage, he found the Ilkeston church in a very dilapidated state.

In particular the chancel was in desperate need of repair before it fell down.

Not everyone was immediately welcoming of the new vicar. The Nottingham Mercury (January 27th, 1843) accused the Rev. George of ‘perambulating’ the town to spread his gospel, suggesting that he was exceeding his calling. “We wish the vicar to understand that his course is watched“.

A sketch of St. Mary’s Church, c1814 (the year of Rev. Ebsworth’s birth), south view

1843: A fractious Vestry meeting

By September 1843 it was time for the members at the Vestry meeting to set the Church Rates (often a contentious affair), made more so on this occasion because of the run-down state of the church’s fabric. The Rev. George set out the state of affairs, declaring that it was Common Law which bound the parishioners to agree to repair the nave of the church, and he was determined to enforce that law. John Ross, who was then Churchwarden, set out in detail what needed to be done and proposed a rate of 5d in the pound, which wasn’t really a proposal, as George pointed out, but more an order !! And no amendments were allowed !! Dr. George Lucas then pointed out that the issue could not be settled if a majority of those present opposed it. The Rev. Ebsworth was having none of it however — to him, the only issue was whether the rate which was set was high enough. Equally, Dr. Lucas stuck to his guns, while others present at the meeting now joined in.

Dr. George Blake Norman, a Conservative and Churchman, opposed the other doctor’s opinion while Matthew Hobson and Francis Ball, both Liberals and Dissenters, supported Dr. Lucas. Moses Mason then suggested the possiblity of raising the money for repairs by voluntary subscription which the Vicar said he would agree to, so long as the amount raised was sufficient.It was clear that opinion on the matter was splitting along political and religious lines, and after a powerful (and lengthy) speech by Non-conformist schoolteacher William Frederick Milner, the Vicar agreed to test the “sense of the meeting“. Of those present only 12 voted for a church rate (six of whom were joiners or bricklayers !!) while 70 voted against. At this result, Churchwarden Ross stated that he would be reluctant to now set a church rate, and there the matter rested … for the time being !!

“Thus have the parishioners of Ilkeston performed their duty, and achieved another victory over the corrupt practices of our state church” the Nottingham Review judged.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

1843-1853: Years of Preparation followed by Improvement

After this cantankerous Vestry meeting financial contributions were made, though not by a Church rate, and repairs to the church were undertaken in the summer of 1844, under the supervision of Mr. Barber of Eastwood. There were extensive repairs to the chancel (a new roof and east window) and additions to that same part of the church, though not to everyone’s taste. Seventy additional sittings were added by the alterations, all free, with open pews and reading desks with kneeling boards, ornamented with poppy heads. The church was thus reopened in December 1844. However within ten years its condition was again causing concern.

“Not only was the interior unsightly and unsuited for the purpose for which it was set apart, but so damp and dilapidated as to prevent many of the parishioners from publicly worshipping in it”.

The church “had fallen into such a state of decay that the health of the worshippers was endangered by the damp and cold; the walls, originally of very imperfect structure, were so much out of the perpendicular that they were liable at any moment to fall; and there was no permanent provision either for warming or lighting. The parish was also rapidly increasing in population, and the area of the church did not allow of any adequate addition to the number of sittings”. (NG)

Cotmanhay Church

It is 1844 and here are the latest figures — Ilkeston has a population of 5329 people, one church with 448 seats, not one of them being free.

This is one reason why plans for another church were hatched, and by March 1846 a new district had been formed and endowed, consisting of Cotmanhay from the parish of Ilkeston, and Shipley from the parish of Heanor, containing initially 2500 persons. The proposed new church building already had a site, donated by the Duke of Rutland, and subscriptions were now being taken, while a grant of £570 was received from the Lichfield Diocesan Church Extension Society.

By September 1846 a Committee of Mangement had been formed to oversee and augment the fund for this church. The target was £2100 and although the total, so far, was short of that amount it was sufficient to enable the committee to give the architect instructions to apply for building tenders. The chosen tender was that of James E Hall of Nottingham. reflecting a total cost of £2200 (without the restorations)

The plans impressed the Committee, “showing the great professional taste and ability of the architect, Mr. Stevens” though some exterior ornamental stone work and interior decorations had initially been cancelled, to cut costs. This ‘downgrading’ hadn’t pleased several members of the committee; Squire Mundy, the Rev. Ebsworth, the incumbent of the new parish, the Rev Symons, and a few others, all dug deep into their pockets and came up with donations to cover the costs of restoring many of the ornaments and decorations.

On April 26th, 1848 Christ Church, Cotmanhay was solemnly consecrated to its holy uses by the Lord Bishop of Lichfield. As the Derby Mercury described it (May 3rd. 1848):

“It is of the first pointed style, and consists of a nave with aisles, and a small bell turret on the western gable. There is unfortunately no chancel; but the eastern window — a handsome triple lancet — being placed within an arch of construction, this necessary portion of a Christian temple may be added at a future time.

A new church at Cotmanhay (from Edwin Trueman’s History of Ilkeston 1880)

“The church is divided into fine bays by circular columns and pointed arches. The interior arrangements are for the most part exceedingly good, and the effect is ecclesiastical and solemn. The santuary is elevated on three steps and surrounded by very neat rails; but the alter should have a foot place, as at present it is almost hidden. The seats are all open, massive, and convenient for kneeling. The centre avenues are of ample width; a circumstance which adds much to the effect of the high pitched open roof. The font, which is a stone one, is appropriately and correctly placed near the west door.

“The church has been erected by Mr. J. E. Hall of Nottingham, from the designs of Mr. H. I. Stevens of Derby; at a cost of about £2500”

————————————————————————————————————————-

On Christmas Day of 1845 the Rev. Ebsworth formally presented a set of sacramental vessels of pure silver to his church; the chalice was a little out of the perpendicular. It seems the chalice and its paten were restored in 1895, the silver being melted down and reformed. The new vessels were used for the first time on Easter Sunday of 1895. Two years later, in September 1897 they were exhibited at the Church Congress annual ecclesiastical and educational art exhibition, held at Nottingham, by the Rev. Edward Muirhead Evans. The pre-Ebsworth chalice was presented to the church by Thomas Harrison in 1692.

In 1851 – according to the Religious Census of that year — the Church had 512 free sittings.

Total morning average attendance was 400 with 150 in the general congregation and 250 Sunday school scholars. The corresponding afternoon figures were 500, (250 + 250).

In his Derbyshire Church Notes, Sir Stephen Glynne described St. Mary’s which he visited in January 1852.

“A large church with several interesting features, amidst much modern alterations and very bad internal fittings.

It has a large chancel, nave with aisles and west tower and the chancel has had once a north aisle now destroyed. The tower and all the west end are modern and incongruous, having been rebuilt 1737.

The nave and aisles are lofty and of equal height with First Pointed* arcades, each of which consists of three tall pointed arches. (*First Pointed architecture equates with Early English, dated 1189-1307.)

The south piers are octagonal with moulded capitals and semi-circular responds.

On the north the arches are rather curious and plain with flat soffits, but an excellent chevron moulding and a nail headed hood moulding, the piers lofty and circular having square capitals and rude early foliage almost Norman

The ceiling of the nave and aisles is modern and flat”

Sir Stephen continued in similar detail to describe the rest of the church interior and exterior, including….

“The east window(in the picture above) is of an earlier** character and has five lancets surmounted by a large moulded arch, having clustered shafts to the outer arch”.

(** earlier than Middle Pointed or Decorated period 1307-1377).

The full description can be found in ‘The Derbyshire Church Notes of Sir Stephen Glynne 1825-1873’, edited by Aileen Hopkinson, Vincent Hopkinson and Wendy Bateman. (Derbyshire Record Society 2004).

————————————————————————————————————————-

1853: Plans for improvement

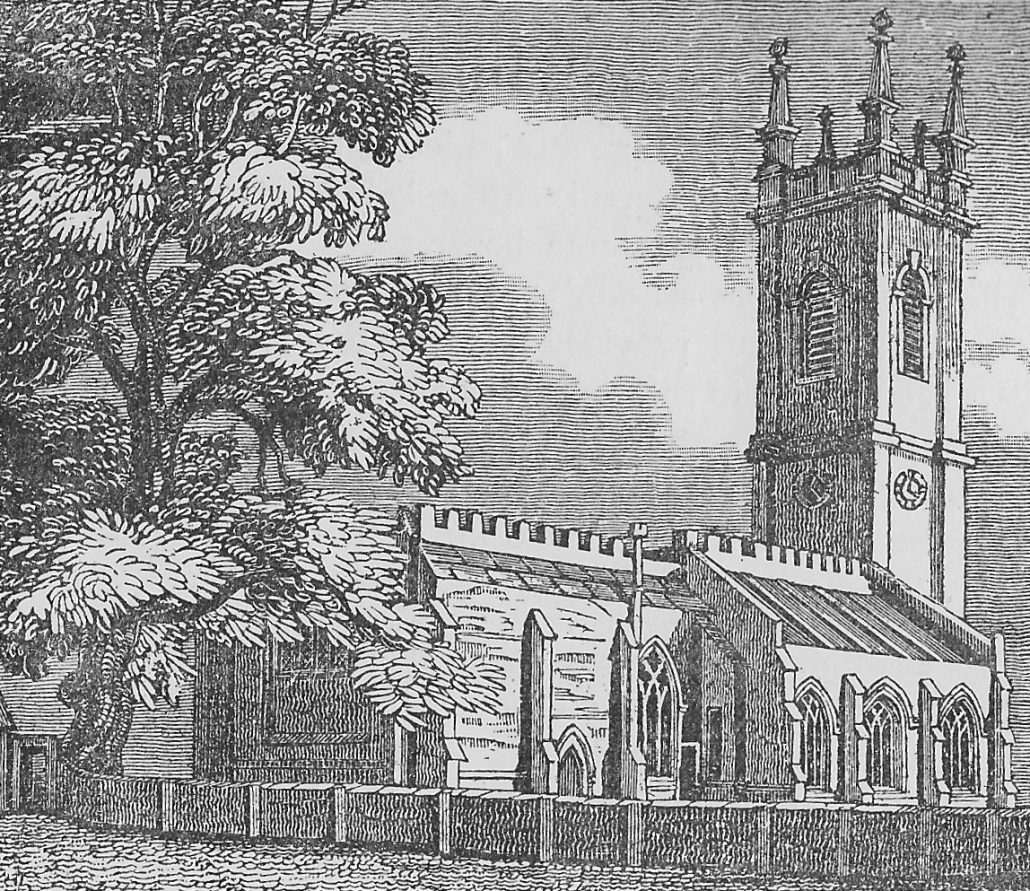

A north view of the church, before improvement

On October 13th 1853 vicar George convened a meeting in the National School-rooms in the Market Place at which plans for improving St. Mary’s were to be discussed. The moments leading up to the meeting were described by ‘the Venerable Whitehead‘ in the Ilkeston Pioneer (October 1853) and he didn’t offer very much optimism …

Two attendees walked to the church-yard … The two lugubrious weeping ashes that stand sentinel at each end of the railed tomb of the beloved Curate (Richard Moxon), looked as much out of place as trees could well look, when our veteran namesake (parish clerk Samuel Whitehead), the half military sacristan of St. Mary’s appeared with the keys. They were admitted by request at the belfry entrance — the Pro-naos of well regulated churches — but here, alas, the coal tub !! The Strangers sighed, the old sacristan sighed, but hoped, octogenarian that he was, to see better things before he said his last Amen. The interior of the church was gloomy beyond description.

It was about five o’clock when four or five ecclesiastics and as many laymen crossed the churchyard on their way to the National School. It was the hour of the meeting. Not a soul had arrived, and for one weary hour did the friends of the church wait for the coming of the ever-tardy-to-come Ilkestonians. Had the travelling theatre, which was standing close by, announced a performance … the case would have been different. As it was, when the long line of gas lights began to twinkle, (people began to arrive).

The Venerable Whitehead (see bottom of the page**) estimated that eventually about 50 persons were present. Chairman George was the first to address the meeting.

“For many years the church of this parish has been suffered to fall into a most deplorable state of decay. Since the year 1734, in which the ancient spire and one of the chancels fell down, and were replaced by the present tower and chancel, little has been done to keep up the fabric. So far however from regretting that little was done during those long years, I think, judging from the unsightly erections of that period, that we have every reason to rejoice that our ancestors withheld their hands, and left us to perceive much of the beauty and admirable design of the original structure, which might not have been the case, had they modernised the building.

“But … many a crumbling mullion, and many a decaying rafter, tells its tale of coming dissolution, and … unless we thoroughly restore this house of God, we shall have more serious accidents than those which have alarmed us of late years”.

He then proposed a resolution, calling upon those present to join him to begin a serious fund-raising campaign and finance a thorough restoration of the church.

West Hallam-born writer Thomas Rossell Potter, who had travelled from his Wymeswold home to lend his support, out of his love for the church, spoke to second the vicar’s plea.

“My heart sinks to think of the wretched state in which this temple of God has been permitted to lie waste. You have here a noble building, with its beautiful sedilia, its exquisitely proportioned arches, unequalled in the Midland counties, its unique stone screen, its high Norman arches communicating with the south aisle, in a state which would disgrace the hut of the humblest mechanic among you. The beauties of the fabric are hidden under the whitewash accumulation of generations of churchwardens, who have no idea of repairing a church beyond covering it with filthy lime. Your pews are like railway trucks, sentry boxes, or pens for sheep; they are good only for enabling one lady to examine another’s shawl and dress. They must all come down; your galleries must come down….

“When we see Ilkeston church in its present state – when we see a board in what was once a most beautiful window – a disgrace to my own house, as it would be to the house of any man: when we see whitewash, cobwebs, and dirt thickly covering the most beautiful carving, it is a sight enough to make a good man’s heart sad”.

Others present added a chorus of support and contributions of nearly £450 were pledged immediately. The fund was started which was to eventually raise £4000 to pay for the extensive building work which began in February 1855.

1853: The Fund

Andrew Knighton writes that “from the 1853 Ilkeston Pioneer (I have a bound volume for the year) a list of donors to the fund. It might have more general interest because of the large number of Ilkeston families listed. Although the print is a bit small to read”.

The chosen architect for the improvements was Thomas Larkins Walker of Leicester, a pupil of the renowned Anglo-French architectural draftsman Augustus Pugin the Elder, and his submitted plans included …

“the re-building of the north and south aisles, and restoring them to their original length towards the west; re-building the chantry chapel… (to)..accommodate 294 school children; restoring the chancel arch; re-casing the tower; adding a vestry on the old foundation of the sacristy, adjoining the south wall of the chapel;.. new seats, new floors, and new steps throughout. His estimate, including the warming and ventilating apparatus, lighting with gas, levelling the ground around the church, and taking in a large addition to the churchyard towards the west, amounted in round numbers to £3,500”. (DM)

The works were to be executed by Messrs. Lindley and Firn, builders and contractors, of Leicester.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

1855: The church is renewed

In March of 1855, when digging the foundations for the new chantry chapel on the site of the old one, workmen removed a solid wall, six feet deep below the surface and six feet wide, below which was a bed of hard solid clay. As they dug this out they came upon a partially decayed ancient oak coffin containing a human body, only slightly decomposed, with flesh still on its bones. “On exposure the stench was most offensive”. The body was carted away in a handbarrow to elsewhere in the churchyard where it was re-interred with appropriate decency. (as recounted in the Nottinghamshire Guardian, March 22nd, 1855)

The burial ground row.

In November 1891 a letter appeared in the Ilkeston Pioneer written by ‘Kensington’ in which he commented on these Church ‘improvements’….

The old tumble-down church was restored about 35 years since, and the (church) yard was extended, taking in a piece of waste ground where rubbish used to be deposited. Wasn’t there a row about it ? But the Vicar was one too many for his detractors, and the Market-place was improved.

The ‘row’ referred to in this letter — which surfaced in March 1855 — centred around extending the present, overcrowded burial ground in front of the church building onto land, originally part of the Market Place — and thus much closer to the population as they went about their daily life. Concerns were raised by some about the ‘health of the town’ suffering as a result, while other residents argued that the appearance of the Market Place would be spoiled — perhaps forgetting that the annexed land was at present being used to house waste and ‘other nuisances’ ?

The old church wall was replaced by a new one, further to the west of the original — some residents looked around for someone, (anyone !!), to blame for this ‘unauthorised’ intrusion. However it was pointed out that the land in question was not public land, owned by the inhabitants of Ilkeston, but was private property, previously owned by the Duke of Rutland but given to the church for the purpose to which it was now being put.

(And it was just a year later, 1856, that an Order in Council arrived, requiring the immediate closure of a portion of the churchyard …. a closure which was to cause trouble for a different Vicar 30 years later.)

The foundation stone to mark the church improvements was laid in the north-east corner of the chantry on Monday, April 8th 1855.

Mrs. Ebsworth inserted a plate-glass box containing coins of the year into the stone, together with an account of the restoration and enlargement of the church, of the day’s ceremony and of the names of the building committee and the subscribers. To mark the occasion a service was held at the Girls‘ National School which had been licensed for public worship during the rebuilding process.

A service of Reconsecration on Thursday, October 18th 1855 saw the re-opening of the church for divine worship. The morning trains from Derby, Nottingham, Mansfield and Leicester brought eager visitors to swell the assemblage.

“At a quarter past eleven, the Lord Bishop of Lichfield was received at the western door, and he entered the church followed by a procession of clergy habited in their surpluses and hoods, the bishop and congregation repeating in alternate verses the 24th psalm, as they walked up the central aisle. (National schoolmaster William Whitehead presided at the harmonium.)

“Having read the exhortation and prayers according to the form, the sentence of consecration was recited by the Rev. G. Ebsworth. It was then signed by the bishop, and duly ordered to be enrolled. …

“At the conclusion of the service, his lordship proceeded to consecrate the burial ground, having done which he pronounced the benediction”. (Morning Chronicle)

In November of 1855 the architect Thomas Larkins Walker presented to the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society an historical account of St. Mary’s, compiled by himself, together with a lithographic print of the church made from his recent restoration designs.

“The peculiar features of interest in the Church consist of the south arcade of the nave, which is a very good example of transition from Norman to early English; the western arch which is pure early English; the chancel which is a transition from early English to decorated; the aisles which are pure decorated, and the south arcade of the chancel which is a transition from decorated to perpendicular. This arcade originally separated a chantry from the chancel; about a century ago the chantry, which had fallen into disuse, was taken down, and a wall built against the beautiful arcade. This chantry Mr. Walker has rebuilt from his own designs, and has given entire satisfaction to the most severe ecclesiastical critics.

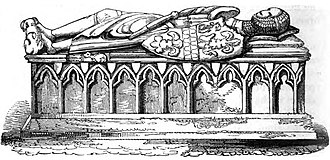

“We understand that Earl Delawarr (sic) has commissioned Mr. Walker to have the Cantilupe (sic) tombs thoroughly restored, his lordship being the representative, as Viscount Cantilupe, of the noble benefactors to Ilkeston from circa A.D. 1330 to 1370”. (NG October 1855)

However it appears that at least part of the tombs was removed by the builders/stonemasons Lindley and Firn and taken to Leicester. It was a “stone effigy of a knight in armour, cross-legged – his head covered with a hood of mail, and mail all over the body, except the knees, which are covered with plates. The effigy is of the thirteenth century. .. It is said to be a Delewar (sic)”. (LC)

When the then Earl of Delewarr (or Delawarr or Delewar!!) learnt of this he agreed to pay for the ‘repatriation’ of his ancestor’s effigy, and Messrs. Lindley and Firn were to undertake that work. And at the beginning of 1858 the Pioneer reported that Lord De La Warr (another alternate spelling !! ) and Cantelupe’s beneficence had borne fruit.

“In the restoration of this monument the most eminent antiquarians have been consulted. They advised that the effigy should remain in its mutilated state, with one or two slight exceptions; but that the pediment should be restored to its original state, since sufficient remained to give a clear indication of what it once was. The manner in which the work has been done, and the correctness with which every detail has been followed, reflects the highest credit on Messrs. Lindley and Firn, who have shown themselves not only workmen but men of good taste”.

The article went on to give a potted (misleading/inaccurate?) history of the Cantelupe family… you might compare it to the account in Trueman and Marston (pp 11 onwards)

The manor of Ilkeston came into the Cantelupe Family by marriage with Eustachia, daughter of Hugh Fitzralph, the lord to whom the charter of the market was granted, A.D.1252. And as the Cantelupes ceased to be lords of Ilkeston in the year 1355, the date of the monument is given within very narrow limits. The tradition is probably true, that the monument is that of Nicholas, who accompanying Edward, eldest son of Henry II, on one of the crusades, died of fever at Malta …… the original chantry was erected by Joan Cantelupe in memory of the crusader. The architecture is of the time of A.D.1330, with the exception of the windows which were removed from the Chancel.

In the spring of 1856, funded by public subscription, an additional alteration was undertaken when the church’s Italian tower was transformed into an early English one. This involved the replacement of the tower’s pinnacles – according to the Nottingham Review, built with the tower 76 years previously – by entirely new ones.

The changes were again designed by Thomas Larkins Walker and completed by Messrs. Lindley and Firn.

P.S. No scaffolding was used during the making of these alterations and no human being was injured !!

…………………………………………………………….

What did others have to say of this ‘renewal’ period ?

Part 1: Extracts from “Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire” Vol.4 (on Ilkeston Churches)

In 1879 J. Charles Cox published his fourth and final volume of “Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire” which “deservedly places its author and compiler amongst the foremost ecclesiastical historians of our time”. (IP June 1879). It contains a chapter on St. Mary’s Church and is far from complementary about the restoration of 1855.

The church underwent a thorough, and, in many respects, most unfortunate “restoration” in 1855*, when the outer walls of the north and south nave aisles were taken down and rebuilt ; and the tower, west end of the aisles, south chancel vestry, and north chancel aisle built new, but on the old foundations. The tower, beneath which is the principal entrance to the church, is a pretentious affair, but singularly poor and bald in all its details. A glance at the carving of the capitals of the shafts in the jambs of the west doorway is sufficient to prove the character of the work. The vestry on the south of the chancel is said to be built on old foundations; and Sir Stephen Glynn(sic), who was here three years before the restoration, remarks that “the priests’ door south of the chancel is set curiously sideways within a large exterior arch, as presented externally.” It would therefore appear that there was also at one time a south chancel chapel. In a pamphlet, issued when the restoration of the church was in contemplation, it is said that there was originally a sacristy on the south side of the chancel. But sacristies are hardly ever found on that side of the chancel, and no such building would require a large archway opening into it.

The lofty arcade of three arches that divides the nave from the south aisle is specially interesting, being of the transition period from Norman to Early English, about the time of Richard I. The pillars are circular, and the arches, which only just partake of any pointed character, are ornamented with the chevron pattern and an outer moulding of the nail-head device. The arcade between the nave and the north aisle is supported on lofty octagonal pillars with plainly-moulded capitals, and is of decorated date, but early in the style. The windows of both the aisles are also of that style, circa 1300, but were rebuilt in 1855. The old patterns were not very carefully followed. The spacious chancel is also of good Transitional character, of the last quarter of the thirteenth century; but the alterations of 1855 were here also apparently of an unnecessarily extensive character.

At the east end of the south aisle is a small piscina niche. In the north wall of the north aisle, near the east end, is a shallow sepulchral or founder’s recess, quite plain. “The font,” says Sir Stephen Glynn, “has an octagonal plain bowl, upon a raised base and kneeling step.” From Mr. Meynell’s drawing (made in 1814), we judge it to have been coeval with the south nave arcade. In 1855, this font disappeared, and we have not been able to trace what became of it. The one now in use is a modern effort, with a good deal of carving about it. The taste or reverence of those who would substitute a new for an old font, however plain the workmanship of the latter, is not to be envied.

Against the south chancel wall is a row of three sedilia, and a double piscina.

There is a remarkable stone screen, dividing the chancel from the nave, having five cinquefoiled, arched compartments, with pierced quatrefoils in the spandrels, and grey marble shafts, of circular form, with moulded capitals and bases, the whole resting upon a stone wall. The doorway occupies the centre arch, and has its shafts rising from the ground. This screen has been repaired at various times. The mouldings of the capitals and bases of one or two of the columns, which are original, appear to be of Early English character, but the general style of the workmanship and the details of the tracery show that it is coeval with most of the chancel work, viz., at the beginning of the Decorated period. It has been thought by some that the marble shafts were not originally designed for the screen, but have been removed from older window jambs ; but we see no reason for such a supposition, which would be entirely contrary to the use of medieval architects.

On the north side of the chancel is an altar tomb, bearing the effigy of a knight, wearing a hood of mail. His feet rest on a lion, and he has prick spurs. The sword-belt is studded. Only part of the sword is now left, and the small lion on which the sword-point originally rested. On the left arm is a large shield, bearing the arms of Cantelupe a fesse vaire between three fleurs-de-lis. The sides of the monument are panelled into a series of trefoiled niches, in the spandrels of which are small, uncharged shields. Nicholas de Cantelupe, first Lord of Ilkeston of that name, died circa 1275-80**, and his son William in 1307. This monument pertains, we believe, to one or other of these knights ; and from the general details and character of the work, we are inclined to think that it is to Sir Nicholas. Previous to 1855, this monument stood in the centre of the chancel, of which Sir Nicholas was probably the founder. Mr. Meynell speaks of it being ” very perfect, excepting that it has been repeatedly white- washed;” adding “a short time since the bones were taken up; they were near the surface in a sort of coffin made of several stones, and the legs were crossed as upon the monument, but no inscription could be found. The bones were very perfect, and the teeth particularly sound and fresh. I had this account from the clerk of the parish in 1814.”

A copy of the sketch made by Godfrey Meynell, of the tomb of Nicholas de Cantilupe. **Trueman and Marston date his death to c1265

The same gentleman (that is, Godfrey Meynell) gives a drawing of another raised tomb on the north side of the altar, the upper slab of which was of Purbeck marble, but the brasses had been taken from it. Sir Stephen Glynn describes (in 1852) the sides of this tomb as being of alabaster, and “having pierced arches, which are trefoiled and hollow within there are three arches on the sides and two at the ends.” This interesting tomb disappeared at the “restoration.”

…………………………………………………………………

Part 2: the disappearing tomb

Let’s just pause here and consider a letter written to the Editor of the Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, appearing on May 18th 1889 — it was written by Charles Kerry, a member of the Council of the Derbyshire Archaeological Society. The letter relates to the last paragraph (above) describing the ‘disappearing tomb‘ at the time of the 1855 Church renewal.

Charles Kerry describes this tomb as found underneath the easternmost arch of the church, between the north chapel and the chancel. It consisted of two large oblong slabs, one above the other, the top one separated from the lower one and supported by an open arcade of stonework. Charles precisely measured the slabs as 8ft 6in by 3ft 7in. At the time of the ‘restoration’ the tomb was dismantled; the upper slab (which appeared to have once had a brass plate attached to it) was carted to the east side of the graveyard, near the wall of the Vicarage garden, while the other slab was placed over the grave of the ‘late vicar’. The separating arcade contained three arches on either side, and one arch at each end; they were removed to within the Vicarage gardens.

A side section of the supporting arcade (from Trueman and Marston p267)

A side section of the supporting arcade (from Trueman and Marston p267)

The slabs, suggested Charles, were made of Purbeck (Dorset) or Petworth (Sussex) marble, while the arches resembled Derbyshire marble. From various clues, Charles deduced that the effigy once found on the tomb, was of a warrior, not a clergyman, and dated it to around 1306 !! Then, looking for a Cantilupe death around that time and associated with Ilkeston, he arrives at William de Cantilupe, son of Nicholas and Eustacia, who died in 1309.

In his letter Charles writes as though the slabs are still complete and not broken up, although the sun by day and the frost by night “will soon have completed the work of disintegration, and in a few years the traces I have so carefully delineated will no longer be visible” He describes long vertical cracks in both slabs, while the lower slab has been cracked laterally. This suggest that both slabs were moved in tact and by 1889, though further damaged, still retained their shape.

In 2001-2, among garden debris in the Vicarage garden, parts of the slabs were discovered … now no longer ‘in tact’

……………………………………………………………….

Part 3: Charles Cox’s account of St. Mary’s Church continues

Mr. Meynell also makes mention of two brass plates to Francis Gregge, gentleman, 1667, and to Robert Gregge, gentleman, 1680. “The church having undergone some alterations the above monuments of the Gregge family are removed, but the brasses are in the possession of the clerk.” Where are they now? He further mentions several more modern inscriptions that cannot now be found, concluding with the remark “These appear to be all the inscriptions now remaining, but many are removed and lately destroyed.” The destruction of monuments in this church certainly seems to have been peculiarly wanton, even for Derbyshire.

In the vestry is an oak parish chest, the carving on which shows that it dates from the Perpendicular period. On the Holy Table are carved the words : ” Ex dono Thome Harrison, qui obiit Octobris Anno Domini 1622.” (donated by Thomas Harrison who died October 1622).

The registers, according to the Parliamentary Return, begin in 1586, but are defective between 1670 and 1679.

*The Pioneer was unhappy about the use of the word ‘unfortunate’ and sprung to the defence of the ‘restoration’.

“The old Church was so thoroughly decayed and unsafe in many parts, that not only was a thorough overhauling of the whole building necessary, but it had in effect to be entirely re-built, and then it became almost impossible to retain its ancient appearance intact, either internally or externally”.

Another defender of the old church – as you might expect — was George Searl Ebsworth, who by 1879 had left Ilkeston and was now Vicar at Croxton Kerrial near Grantham. The day after J. Charles Cox’s book had been reviewed in the Pioneer, George wrote a letter to the same newspaper, which was printed the following week.

“Sir, — I think it will be satisfactory to the parishioners of Ilkeston to be assured that the restoration of their Parish Church was carried out in the most conservative spirit. Nothing was pulled down which could with safety be allowed to remain. The greatest care was taken that the minutest details should be faithfully reproduced. To this end the architect and a very competent assistant spent fourteen days in taking measurements and forms of the mouldings, &c, previous to making the plans. The north aisle walls fell down when the roof was removed. The foundations of the chantry walls and of its buttresses were discovered three feet under the surface, and the new chantry was erected upon them. The arcade separating the chancel from the chantry was about two feet out of the perpendicular. As it was taken down each stone was marked, and afterwards restored to its place.

“The marble part of the screen was copied from pieces found in the old wall which had been built up to preserve the upper portion, which is of Ancaster stone.

“It is to be regretted that want of funds prevented the tower from being completed according to the first design, which was admirable. The present work was determined upon by the churchwardens, who could not bear to see the shabby Italian tower when the rest of the Church was restored.

“ I think it due to the memory of the architect, Mr. Larkyns (sic) Walker (pupil of the elder Pugin, and continuator of his architectural works), that these facts should be known. I am quite prepared to vindicate every part of the restoration for which Mr. L. Walker was responsible; he was a man professionally in advance of his time, and many of his suggestions – received coldly when put forth – are now adopted by our best architects.

I am, Your obedient servant, G. SEARL EBSWORTH, Late Vicar, from 1842 to 1863.

————————————————————————————————————————————–

1856: The Church after renewal

St. Mary’s Church c1856, from the south-west (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library.)

Writing in his ‘Jottings’ column of the Ilkeston Pioneer (December 30th 1932) ‘Rambler’ referred to this painting.

“I have before me a picture of St. Mary’s Church on a summer’s evening, with the parishioners wending their way to church, painted in 1856. It is the more interesting because the figures represent well-known townspeople of that day. A local lady to whom the picture once belonged knew whom the figures represented. Unfortunately she never committed a list to paper and as she paid the debt to nature many years ago, it is not likely now that they will ever be known. In the apparel of these old Ilkestonians tall hats, poke bonnets, crinolines and parasols are prominent. Several of the boys are sporting ‘toppers’. Raising the hat was a custom in 1856, as at least two of the figures are showing this courtesy.

“The Market Place at the Church gates was unbroken by any road or pavement, and on the left is shown a portion of the old building, removed many years ago, and known as the Butter Market”

I believe that the original painting is held at the Erewash Museum.

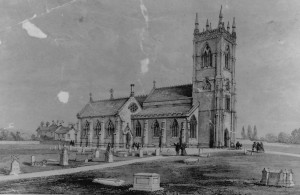

A north-west view of St. Mary’s Church 1856, from a litho print published by John Wombell. (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library)

And a south-east view from the Ilkeston and Erewash Valley Almanac of 1857. (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library)

At Christmas in 1856 vicar George was at the Butter Market (or ’Town Hall’) with his churchwardens and parish officers distributing cloth and flannel to the poor of Ilkeston provided by Gisborne’s charity, set up in 1817. (See the Alms Houses and Ilkeston’s Charities).

On the scene appeared lace manufacturer Joseph Bailey, a Guardian of the poor of the parish to oversee the process and ensure that the presents were given out without favour or bias — but the vicar’s Christmas spirit seems to have deserted him and he took exception to this intrusion. In previous years his deeds had been misrepresented by the Guardians and he wasn’t going to allow that again. He wanted Joseph to leave his room and called for the constable to remove him. Joseph was not a man to be trifled with however, and stood his ground, warning the constable to ‘be careful’. The vicar was also determined and ordered Joseph’s instant removal, promising to support the constable in his action both now and in the future.

Joseph was then ‘collared’ out of the room.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

1863-1894: The Rev. George’s post-Ilkeston days.

George left Ilkeston in 1863 for the vicarage of Croxton Kerrial near Belvoir Castle and was succeeded by James Horsburgh. When the former left, on behalf of the parish Dr. Norman presented him with a silver dessert stand, consisting of a figure of Autumn, 20 inches high, with leaf and tendrils of vine in its hands, standing on wheat ears.

N.B. The departure of George was bad news for future genealogists. In the Parish Records he had almost always recorded the date of birth of any child brought for baptism (as well as the baptism date). That convention was not followed by the next vicar.

Mr Ebsworth made one of his several return visits to the town in April 1866 at the opening of the organ in St. Mary’s Church — the Rev. Horsburgh had been called away to Herne Hill, Surrey, after the death there of his only surviving sister, Jane Frances, the wife of Lieut-Colonel James Horsburgh MacDonald, late of the Bengal Artillery

And a happy event for the Ebsworths, November 1873 ……

From the Ilkeston Pioneer Nov 13th 1873

And in June 1879 the Rev. Ebsworth was making another ‘guest appearance’ at St. Mary’s Church.

Still evidently very popular among his former congregation, the attendance at the morning service was large but the church was packed in the evening. The space before the Communion Table and the pathways of the aisles were full.

George’s sermons were “eloquent and powerful, showing that he had lost none of the fire and energy which characterised his ministry at Ilkeston”. (NG)

George Searl Ebsworth died at St. Leonards-on-Sea on October 30th, 1894, aged 79. He was buried at Church-in-the-Wood at Hollington, Sussex, close to his home at Holly Bank, Hollington Park.

** The Venerable Whitehead wrote several articles for the early editions of the Ilkeston Pioneer, 1853 onwards, and in several of them he gave clues to his identity. They point to the anonymous writer being Thomas Rossell Potter (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Rossell_Potter)

———————————————————————————————————————————————

Let’s move on to the next Vicar at St. Mary’s