Peculiar remarks

As successor of George Searl Ebsworth, James Horsburgh was ‘a man who made peculiar remarks’.

Whilst he was Vicar of St. Mary’s he accompanied the choir to Wingfield Manor, where stands a tower in a field, upon which the choirmen climbed with the vicar and his party, the latter standing on one side of the tower and his choir on the other.

“William Flint remarked, “Birds of a feather will flock together!”

“The Vicar heard the remark, turned round, and said “Who made that remark?”

“” Mr. Flint”, said one of the other choristers.

““I thought so”, said the vicar, “because I saw him going down Bath-street with a donkey the other day”. (Gisborne Brown)

—————————————————————————————————————

A new organ

In April 1866 James received the sad news from Herne Hill in Surrey that his only surviving sister, Jane Frances, had died. In January 1835 she had married James Horsburgh Macdonald, later Lieutenant Colonel of the Bengal Artillery, Indian Army.

It was not surprising therefore that James was absent for a joyous event on the following day, when a ‘new’ organ, placed near the east window in the Chantry of St. Mary’s Church, was opened.

It stood about 30 feet high and had been built by the renowned organ-builders Messrs. Bishop and Starr of London, originally for the Church of St. John’s, Paddington. There, shortly after its installation, it had been ‘tried out’ by Felix Mendelsshohn — his verdict was that it was the very best that he had played upon in England. When a member of the congregation of that church offered a new organ costing £800, the ‘old’ organ was thus surplus to requirements — and so found a new home in Ilkeston, but only after it had been altered and extended. In the opinion of Charles Augustus Bishop, son of the firm’s founder, these changes improved the organ such that it was in every way in a far more efficient state than when it was built.

At the service for the opening, the organ was played by Thomas Dixon of St. Wulfram’s Church, Grantham, and the sermon was preached by the Rev. Ebsworth, late Vicar of Ilkeston and now of Croxton Kerrial. This was followed by a luncheon at the Boys’ National Schoolroom and a musical concert in the evening at the same venue.

More sad news for James in November 1866 when his mother-in-law Amelia Edwards, the widow of John Stuart Edwards, of Stanton Lacey, Shropshire, died at Ilkeston Vicarage while on her customary winter visit with her daughter Amelia and her family.

Church outings

In 1867 the Pioneer noted that “of late, treats by the Clergy to Parochial Choirs and Sunday School teachers have become general in this locality, and we hail the step as one in the right direction”.

In this recent spirit the Rev. Horsburgh invited St. Mary’s choir members and teachers to join him for a day trip to Alton Towers, seat of the Earl of Shrewsbury and Talbot.

Alton Towers (https://www.altontowers.com/about-alton-towers/heritage/)

Thus one Friday in late August, the pious band, 45 in number, took the early train, arrived at AltonTowers just before noon and quickly settled down to a picnic dinner. Usual viewing days were Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, but this party had been granted a ‘special pass’ by the estate steward and now set off to view “a most charming scene of grandeur, resembling a miniature paradise”.

What was in store?

They were over 140 years too early for ‘The Blade’ or ‘Nemesis’ in the Forbidden Valley but they were not seeking such attractions.

The Pioneer provided a lengthy description written by Scottish garden designer John Claudius Louden of what might be expected.

“Earl Charles began to ornament the spot with garden buildings about 1814. On visiting Alton Towers, by the road leading from Uttoxeter, we came unexpectedly close to the house, and near the head of the north side of the valley, which contains the chief wonders of the place. The first objects that met our eye were the Gothic bridge, and the embankment leading to it, with a huge imitation of Stonehenge beyond, and a pond above the level of the bridge alongside of it, backed by a mass of castellated stabling. Further along the side of the valley, to the left of the bridge, is a range of architectural conservatories, with seven elegant glass domes, richly gilded, designed by Mr. Abraham; further on, still to the left, and place on a high and bold native rock, is a lofty Gothic tower or temple, consisting of several tiers of balconies round a central staircase and rooms, the exterior ornaments are numerous, and resplendent with gilding. Near the base of the rock is a cork-screw fountain of a peculiar description, which is amply supplied by an adjoining pond. Behind, above, and beyond the range of conservatories, are two lakes, and beyond them is another conservatory, curiously ornamented; below the main range of conservatories is a paved terrace walk, with a Grecian temple at one end, and a second terrace, containing a second range of conservatories. The remainder of the valley to the bottom, and on the opposite side, display such a labyrinth of terraces, curious architectural walls, trellis work arbours, vases, statues, stairs, pavements, gravel and grass walks, ornamental buildings, bridges, porticos, temples, pagodas, gates, iron railings, parterres, jets, streams, ponds, fountains, seats, caves, flower baskets, waterfalls, rocks, cottages, trees, shrubs, beds of flowers, ivied walls, moss houses, rock, shell, and root work, old trunks of trees, &co., that it is utterly impossible for words to give any idea of the effect”.

An afternoon spent in this environment was followed by an excellent tea, and a visit to the Nunnery.

The weary group then headed for the station and reached home by the last train.

—————————————————————————————————————

It’s Christmas time in 1867 and the Pioneer is far from being in festive mood and wishing good cheer to all men!

“On attending the Church of late, it has been a matter of deep regret to notice the disgraceful behaviour of the children who assemble on a Sunday evening. Laughing, talking, and even whistling is practised with impunity, to the perpetual annoyance of the congregation, many of whom repeatedly leave their seats to remove the delinquents to some conspicuous part of the Church, where they may be more exposed to the view of the congregation, in the hope of shaming them, but so incorrigible have they become that such a course has not the slightest effect. We would recommend that some of the offenders be brought before the magistrates, which might perhaps deter others from repeating such proceedings in a building set apart for such sacred purposes, and where solemnity alone should be observed. It is to be feared that many parents disregard the words of the wise King Solomon, in not exercising that chastening love which is absolutely requisite in “training up a child in the way that he should go”, and thus, by sparing the rod, spoil their son”.

—————————————————————————————————————

A religious census

The agitation by Liberationists for the disestablishment and disendowment of the Church of England was heightened in the late 1860’s and early 1870’s. As part of this debate and to show that the nonconformists were numerically the stronger in the country, the Dissenters of Ilkeston conducted a ‘Religious Census’ on the first Sunday in April 1871.

This was a local and unofficial ‘counting of heads’ and not one organised by either Central or Local Government.

The returns showed that over three times as many people attended nonconformist chapels as attended the Established churches in the town. However in a rebuttal to these conclusions Edwin Truman wrote to the local press, pointing out what he perceived to be several flaws in the statistics and methods of collecting them, viz.,

1 …. the Dissenters had kept the taking of the census a secret from ‘Church people’ whilst encouraging their own followers to attend chapel on that day and ‘bring half a dozen more with them if they could’.

2 …. only worshippers going in via the main entrance were counted at the Established churches.

3 …. children attending the Church Sunday schools seem to have been overlooked.

Edwin’s own estimate was that evening attendance at St. Mary’s Parish Church, at Christ Church in Cotmanhay, and at the two Church Missions was almost twice what the Dissenters had calculated, “and this without the slightest exaggeration”.

—————————————————————————————————————

a forced departure

In August 1873 the Rev. Horsburgh was forced to resign “in consequence of domestic affliction” — his wife Amelia’s protracted illness — and his congregation, through Richard Smith Potts, expressed “deep and wide-spread regret at losing so dear a friend”.

“His liberality, his spirit of forgiveness, together with his familiar manner of discourse both in public and in private endeared him to all who came within the circle in which he moved”.

He was ‘rung out’ by a merry peal of the church bells, “a somewhat ambiguous, if not incongruous, mode of taking leave”. (IT)

James received parting gifts from the Church Mutual Improvement Society, of which he was then President, (a Queen’s Reading lamp), from the National Girl’s School and teachers (a silver inkstand), from the Boy’s scholars and teachers (a carved oak reading-desk), and from the members of his church community who presented him with an epergne ‘of a very chaste design’. (Google?!!)

James had asked to exchange benefices with a clergyman in the South of England, and thus, with the consent of the Duke of Rutland, he became vicar at the Church of St. George in Waterlooville, Hampshire, exchanging livings with the next vicar at Ilkeston parish church — John Francis Nash Eyre.

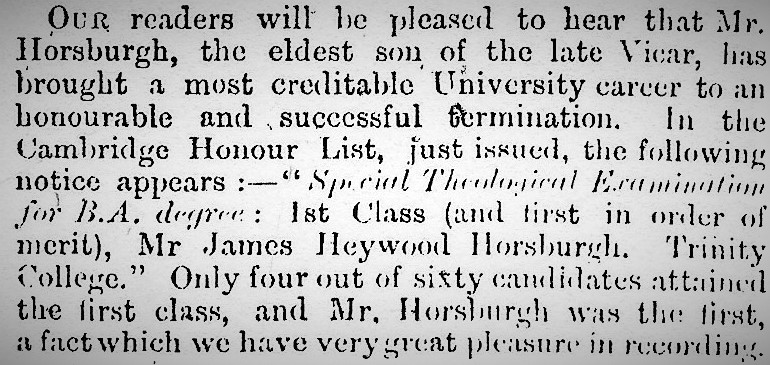

James’s eldest son was James Heywood Horsburgh who, as a young man, achieved great academic success, recorded in the Ilkeston Pioneer (Dec 18th 1873) …

James junior then was the curate of St. Pancras in 1876 when he was admitted to the priesthood at an ordination by the Bishop of London in St. Paul’s Cathedral on St. Thomas’s Day (December 21st).

While still at Waterlooville, James Horsburgh senior died, aged 77, on February 13th, 1899 at Blackwater House College, Eastbourne, the residence of his youngest son. His wife Amelia had died there in January 1881, aged 57.