The Lower Market Place

In the centre of the old (lower) market place and in front of the Butter Market stood at one time the last Maypole, halfway up which was a figure of King Charles II embosomed in branches of oak.

If you would like a little more detail, try this from Edwin Trueman‘s History of Ilkeston (1880) …..

….. an antique stone cross of exquisite workmanship — it was coeval, perhaps, with the oldest portion of the Church. To decorate this on all festal occasions was accounted a pious duty. The base of this stone cross was still standing until the early part of the present (nineteenth) century. It was hollow, and in this hollow was inserted a tall pole. The decorations consisted in weaving round this pole a pyramid of oak boughs, beginning with a base of several yards in diameter, and ending in a point surmounted by a flag. In the centre a little waxen figure was latterly placed called “Charles in the oak”, evidently a comparatively modern substitute for the infant Saviour. Many of the leaves of the column were gilt wth tinsel, and the effect was inexpressively pleasing.

Perhaps Edwin had been reading the Ilkeston Telegraph of 1871 before writing his ‘History’ .. in that newspaper, a letter-writer, ‘Rolling Stone’ , described a stone cross in the centre of the (lower) Market Place as the focal point of the May-day revels known as ‘Illson Cross Dressing’ — held on May 29th or Holy Thursday.

The base of the cross** was still present in 1809 and in the base ‘a receptacle in which it had been customary to insert a tall pole on this festival and around it to form a pyramid of oak boughs surmounted by a flag. In the centre a small figure was placed called ‘Charles in the Oak’. When or how the cross was removed history does not state’.

** In the Ilkeston News of December 21st 1857 there is an account of a civil case for damages, held at Belper County Court, between the plaintiff John Poole and the defendant Edwin Wragg (the case described elsewhere).

It involved a dispute over premises opposite the Butter Market and neighbouring the Old Harrow Inn.

Within the testimony it mentions that the “ancient Cross-stone stood about 10 feet from the plaintiff’s back door” … the Market Cross was shortly thereafter removed. ….

…. Suggesting that at some time in the first half of the nineteenth century the Cross was moved from outside the Butter Market and across the Market Place to the rear of the shops opposite.

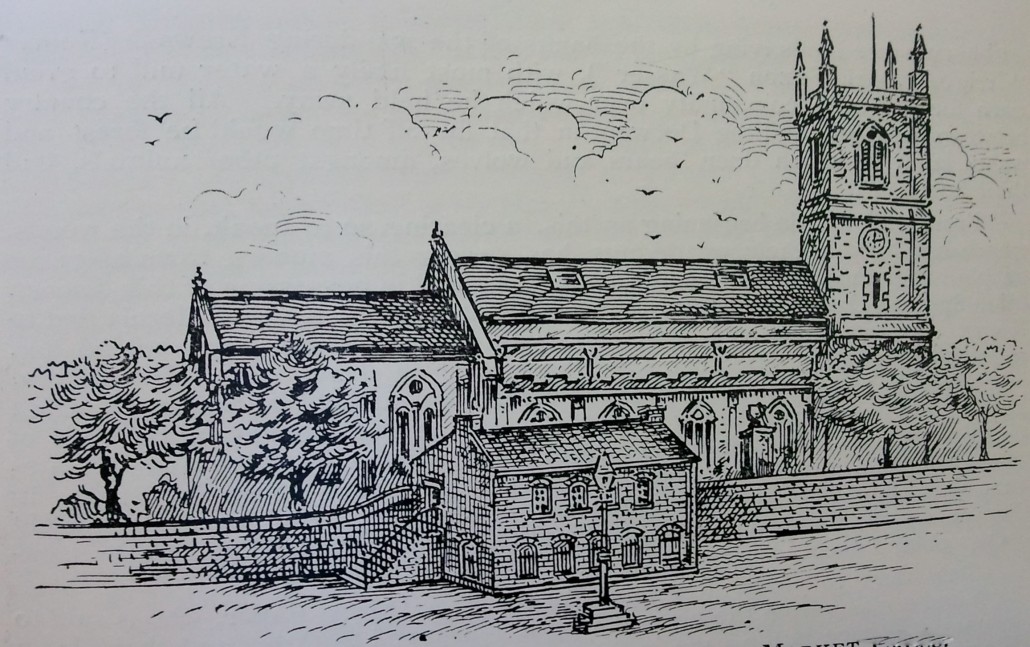

Trueman and Marston (1899) locate the base of the Old Market Cross in the Garden of Dodson House in Burr Lane. The base was later moved into St. Mary’s churchyard. (above)

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Gisborne Brown recalled an alternative structure.

“I will now say a word about a lamp-post that stood in the centre of the Market-place, in front of the Butter Market. It was elevated on four stone steps, the post itself being some 10 or 11 feet in height, with arms extending east and west, with a lamp at each end. These gave a very good light, which was very much appreciated by the public, and there was much grumbling when the post was pulled down”. (IP 1917)

Writing in 1854 Venerable Whitehead let his imagination wander as he pictured what the lower Market Place area might look like in 100 years’ time.

The unsightly and useless Butter Market would be gone, to be replaced by ….

“a covered colonnade the whole length of the Church-yard north wall, skreening the brick walls, forming a dry and pleasant promenade for pedestrians in rainy weather, and a convenient shade and shelter for the market people on market days. It will be in fact in the Paxtonian or Crystal Palace style, having iron pillars of Gothic pattern harmonizing with the style of the Church, and forming as it were a basement to that then perfectly restored fabric – and then people will wonder that the ugly old Market House had been tolerated so long”.

And was he correct?

What had replaced this ‘ugly old’ Hall by 1954?

One evening in the 1860’s Old Resident was standing in this area, opposite the shop of Thomas Merry, the attraction being a couple of itinerant quack doctors, selling their pills and potions from a wagonette under the northern side of the churchyard wall. Suddenly they were drenched by a bucket of water which cascaded over the churchyard wall. Their audience was highly amused but the quacks were not! One of them vaulted the wall, pistol in hand, chasing a gang of rapidly retreating youths who escaped capture — or worse? — by hiding in the heating chamber underneath the church.

On another occasion, the same youths, from the same vantage point, managed to attach a rope around the support of a visiting and temporary shooting gallery. A sharp heave and the whole structure collapsed.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Upper Market Place

The Market Place in 1850, from an oil painting. (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library).

As we now walk into the upper Market Place area towards South Street, we would note that in the 1840’s and 1850’s it was not the open space that we see today.

In front of the church, on its west side, was a homestead, the property of the Duke of Rutland. In the latter years of the eighteenth century this was tenanted by farmer Richard Hawley who died in 1793. Just over a year later his widow Elizabeth (nee Beardsley) married blacksmith and farmer Robert Burgin-Richardson and the homestead was now tenanted by Robert.

Writing a letter to the Pioneer in 1891, Bath Street described what he recalled of the area in 1838 …

“Mr. (William?) Skeavington’s farmhouse and yard stood in the centre of the present Market-place; Mr Frost’s house (in South Street) was not yet finished. Mr. Skeavington was its first occupier after its completion and then the farmhouse and buildings were pulled down”.

We shall shortly visit Mr. Frost’s cottage.

Further building in this area was to follow, as we have seen. (see Education in Ilkeston).

In 1851 the Girls’ Church School was built in the upper Market Place, followed in 1861 by the Boys’ School.

The time is October 1867 and the place is the ‘Junction’, that part of the Market Place in front (north) of the Boys’ School and in line with St. Mary’s Church tower.

Ilkeston is visited by ‘an itinerant vendor of goods’ rejoicing in the name of ‘Ready’ John Stokes of Sheffield who rented a pitch there, at 6d a day, and spent a fortnight doing a roaring trade from his caravan.

He was also ‘hacking off’ the local tradesmen who moaned about their weekly takings being considerably reduced as a result. ‘Moan/hacking’?

On the Saturday he was given his notice to quit by Samuel Pounder, the Surveyor to the Local Board, because the dealer was now causing an obstruction of the highway and people were complaining that they couldn’t get their carts through the Market Place. As he couldn’t pack up immediately, John decided to stretch his luck and trade for another day.

And there he was, about eight o’clock at night, still ‘pursuing his calling’ when the attack on him began.

The ammunition was rotten eggs and rotten pears, raining down on him and his stock, breaking his glass cases, damaging his merchandise.

“One of the eggs fell on the back of a man named Wilkinson from Little Hallam, and it was deemed advisable to immediately put him into quarantine, the aroma arising from the smashed egg being the reverse of pleasant”.

Through this barrage, the valiant vendor was able to identify the point of attack — the church tower — and he summoned reinforcements in the shape of railway porter Henry Blatherwick, greengrocer John Robey, framesmith Alex Cordon and Police Inspector Brady, who were later to be joined by PC William Colton, the Churchwardens and George Blake Norman.

This intrepid band then began their assault on the blackguards hiding in the Tower but their counter-attack on the Church proved futile … it was soundly locked !

Clearly the keys were needed.

But who would have them ?

The Parish Clerk and Church clock-winder John Fish was the obvious man to find.

But where was he?

Why not try the obvious place at this time of night ! ?

But John wasn’t in his ‘local’.

By about 11 o’clock the Vicar had put in an appearance and somehow access was gained to the church, candles were lit, the doors to the tower forced open and up went the fearless adventurers.

Henry Blatherwick led the way and found a basket, empty of ammunition save for one rotten egg and a few pears. He also discovered a bootless William Trueman sitting among the bells. His accomplice, James Aldred, had already been discovered, lying in a corner of the tower.

Both men were quickly escorted to their ‘lodgings’ at the Town Hall lock-up and charged with being in the church for an unlawful purpose.

William Trueman was soon remorseful; “we have been led into it for a lark, and now we have got ourselves into a mess”.

The two also got themselves into an appearance at Smalley Petty Sessions a week later.

Part of their defence was that it was all ‘Ready’ John’s fault. He had been ordered to leave the site at the ‘Junction’ and had failed to do so, on time. The defendants were therefore provoked into stimulating his departure.

And it was all an amusing lark anyway!

Unfortunately the three magistrates had all had a ‘sense of humour bypass’.

William and James were convicted, fined 12s with 16s damages and £1 2s costs.

The Pioneer printed a contemporary account of this case and it was also recalled by Old Resident, an eye-witness to the hostilities, in the same newspaper 50 years later. The latter suggests that there was a wider conspiracy to run the hawker out of Ilkeston, that numerous clandestine meetings plotted his ejection from town and that several people were involved in the collection of ‘ordnance’. William and James were just the two chosen to put the plan into action.

Old Resident identifies William Trueman as ‘the professional cricketer’ and James Aldred as a lace hand and relative of William.

Born about 1827 James Aldred was the son of cordwainer Samuel and Lucy (nee Scattergood) and was living in Bath Street in 1867 with his wife Eliza (nee Thompson) and their children.

Eliza was the youngest child of framework knitter John and Fanny (nee Chambers) and had been born just a few months before the death of her father in 1827. Two years later her mother married widower Thomas Scattergood – he already had at least 11 children during 22 years of his first marriage – and they had three children, one of whom was Emily Thompson Scattergood, born in 1832.

Emily married Hassock Lane lacemaker William Boam in May 1852 but within months she was a widow when her husband died of typhus. Three years later she remarried to widower William Severn Trueman who was born in 1832, the illegitimate son of wheelwright William Severn and Ann Trueman and whose first marriage was less than a year old when his wife Mary (nee Beardsley) died.

Emily died in Calais in April 1867, a few months before the assault from the tower and when she was described as ‘wife of William Trueman, cricketer late of Ilkeston’.

Now — if you have followed all of that — you will recognise that James Aldred was related to William Severn Trueman — he was the half-brother-in-law of William’s late wife !!

Mind you, with that pedigree, he was also probably related to half the population of Ilkeston !!

Gisborne Brown (in the Pioneer of 1917) writes of “a man named Bill Trueman, standing some 6ft. in height and well-built, … called the ‘big-hitter’, because he once knocked the ball over the Parish Church and was allowed extra runs for it. I heard men say that he only took six strides to run the length of the wicket”.

By the end of 1883 the footpath and carriage-way in front of St. Mary’s Church and over the old Cricket Ground had been improved.

There was thus now a direct link from the Market Place to Nottingham Road.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Junction

In a letter to the Pioneer, dated September 8th 1870, an Old Ilkestonian complained that a new schoolmaster’s house for the two National Schools located in the Market Place was to be built “on the Junction in the Market-place beween the two schools”

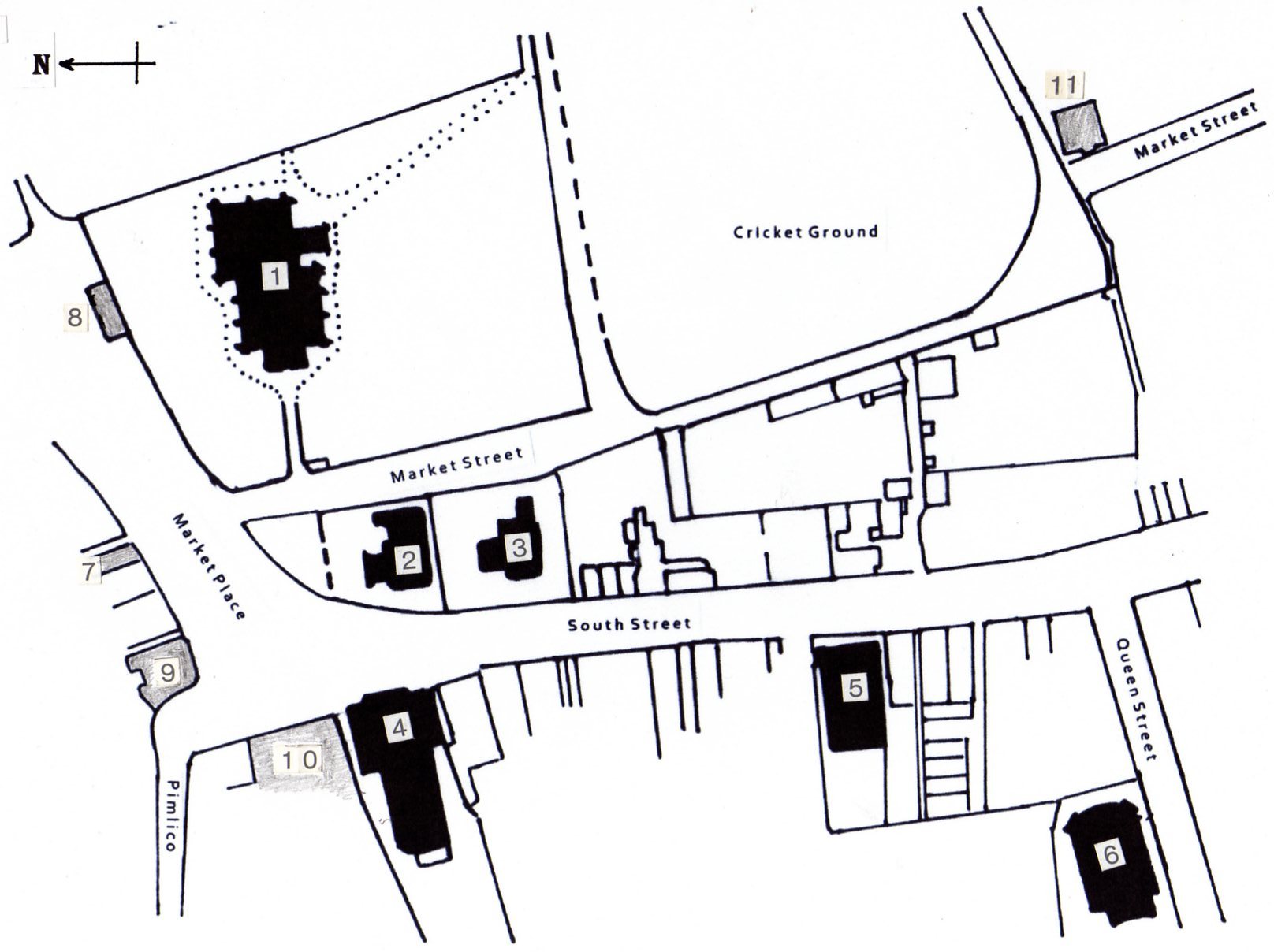

This would place it between the two sites labelled 2 and 3 on the map (right). A detailed key to the map can be found here.

In the same letter, the writer suggested that “the Junction ought not to be appropriated to the erection either of schools or cottages, but for markets, fairs and other public purposes”

The ‘Junction’ was also the area chosen by Noakes’s itinerant theatre when it made frequent visits to the town in the 1860’s, eschewing Aldred’s Yard. There it set up its tent, inside which the audience, seated on bare boards and enduring a keen wind through the canvas, spent an enjoyable evening at the ‘Rag show’.

“I can well remember being taken to Noakes’s show by my father on a particular night, probably in 1859, when the play was ‘Three-fingered Jack’, and I heard sung for the first time that good old-fashioned song I should like to hear again, ‘Ever of thee fondly I’m dreaming”. (Old Resident)

Samuel Taylor … the Ilson Giant

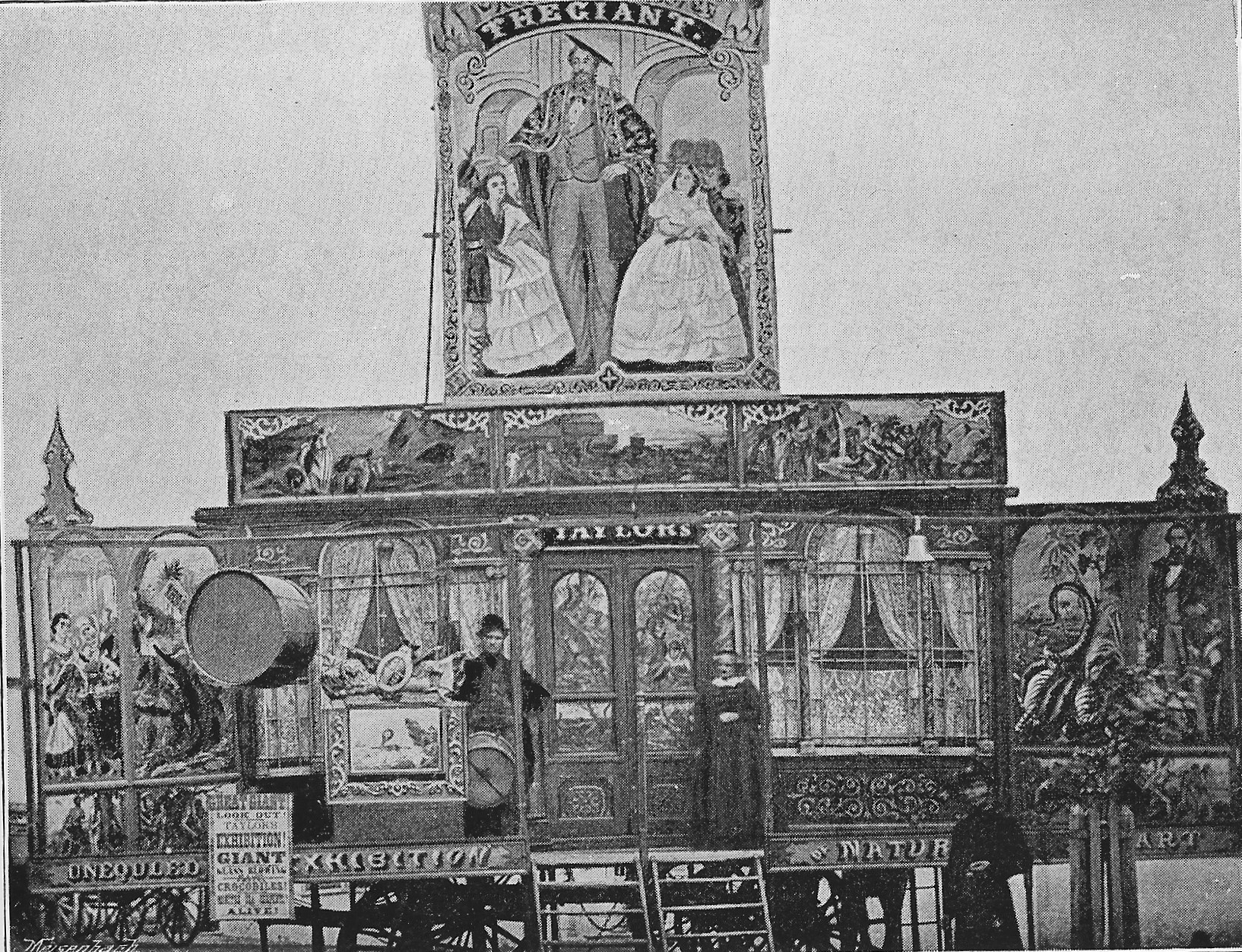

And the same writer cast his mind back again, to 1860, or thereabouts when for several winters in succession Ilkeston was treated to “the exhibition of Samuel Taylor, the Ilkeston Giant (which) was located on the ‘Junction’ for three or four months. During that time his horses were utilised in doing team work for the Stanton Iron Co., which was a very modest concern then …

“The ‘show’ was open two or three times a week, and was well patronised. The programme consisted of glass-blowing by Mrs. Taylor (who looked like a pygmy when standing beside her husband), the showing of a number of more or less wild animals, followed by dissolving views mainly descriptive of the Crimean War, and last, but not ‘least’ by any means, by the appearance of the giant himself. His height was 7f.t 4in. and the ‘tallest gentleman in the company’ was always invited to come forward and stand beneath his outstretched arm. Most of my spare pennies – and they were very few in those days – went into the giant’s coffers … This remarkable man is buried in the Stanton-road cemetery, Ilkeston, where there is a handsome granite monument over his grave”.

Perhaps Samuel’s entertainment career was ignited when the Nottinghamshire Guardian (November 14th 1846) noted that there was a man at Ilkeston, seven feet and six inches tall, employed at leading ironstone from the pits, at Stanton, to the furnace. The article expressed incredulity at his size but nevertheless reported it, and added his name — Samuel Taylor — and his place of brth — Little Hallam, in the parish of Ilkeston. And now, that carrer had ended. At the time of Samuel’s death, in 1875, the Ilkeston Pioneer repeated a few details of his years before …

He was born in Little Hallam in the year 1816. Son of a farmer, he stood 6’9” in height, his own mother being only 5′. His father died when he was 18 months old, so his mother had to provide for the family.

Due to his extraordinary height, he found it difficult to obtain a situation in his native village. One day he visited the Castle Donnington Statutes, offering himself there for a situation. A giant was being exhibited in a show there, and as Samuel had never seen such a show before, he paid his penny to see the man. (Judging by the painting on the outside of the van, he expected to see a man about 14′ tall, and much larger than himself.)

In Samuel’s own words, “I entered the exhibition — a curtain was drawn — and I discovered a man about 6’3”. All eyes turned on me, I stood beside the giant and made him look insignificant. He did not seem much to like the comparison. When I was leaving the showman tapped me on the shoulder and asked if I would accept an engagement to travel, and be exhibited as a giant. I laughed at the idea”. However the offer was so good that Samuel accepted the situation…”

And the rest is history.

Samuel Taylor’s Exhibition (from Trueman and Marston)

Samuel Taylor’s Exhibition (from Trueman and Marston)

Another visitor to the exhibition was Sheddie Kyme who concurred with much of what Old Resident could remember and added an up-to-date magic lantern display, two reptiles and a crocodile.

‘Tilkestune’ (IA 1929) recalled the show’s waxworks and the Giant’s brother, who exhibited some enormous snakes at the front of the show, where Samuel “stood in the doorway and everyone who entered could go under his arm…. Taylor was so tall that he harnessed his horse completely while standing on one side of it. He simply bent over the animal while fastening the harness on the other side”.

Samuel Taylor (from Trueman and Marston)

One day in early 1875 while packing up his show at Oldham, Samuel slipped from the roof of one of his caravans and later died from his injuries.

“I well remember the news reaching the town of Sam Taylor’s death, and Ilkestonians were generally pleased to learn that it had been decided to inter his remains in the town of which he had spent, at any rate, a great portion of his younger days….

“….. So the career of one who had played a prominent part in the Statutes of Ilkeston for many years, was brought to a close”. (Sheddie Kyme)

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Though the exhibition did not die with Samuel.

It was remodelled “on more modern lines, a mechanical arrangement, representing a storm at sea, being the principal feature. This disclosed a ship in distress, going to pieces, as it were, on the rocks – and all to the strains of ‘The White Squall’, that song which sets forth so realistically, the roll and pitch of the vessel, as it rises and falls with the billows”.

The Pioneer described this area as a temporary home for ‘the filthiest exhibitions, designated shows, shooting galleries, steam screeching roundabouts, and caravans innumerable’. (1882)

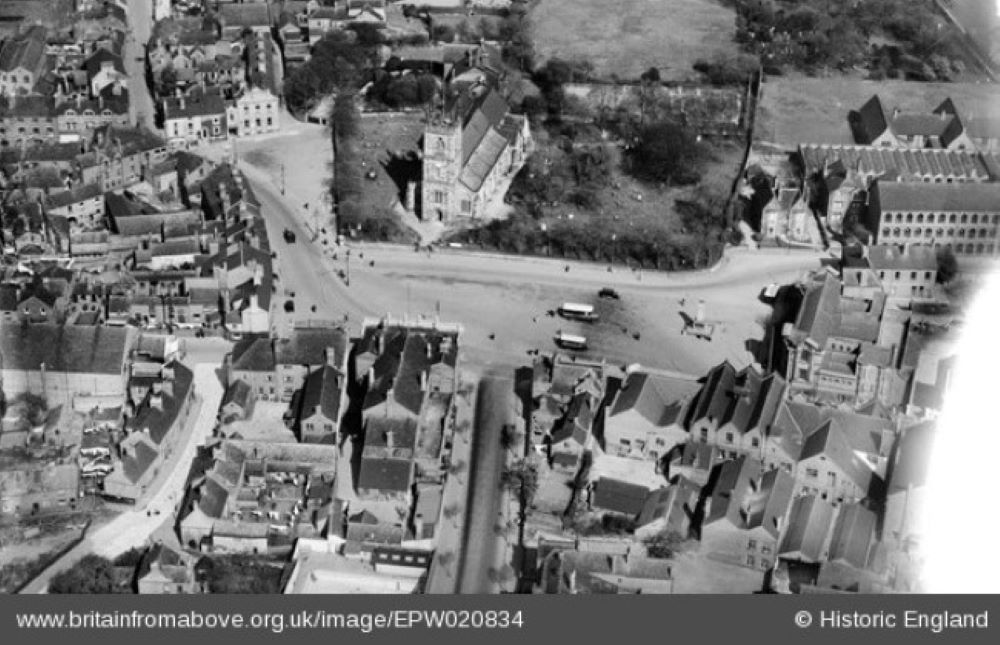

The Market Place in 1928

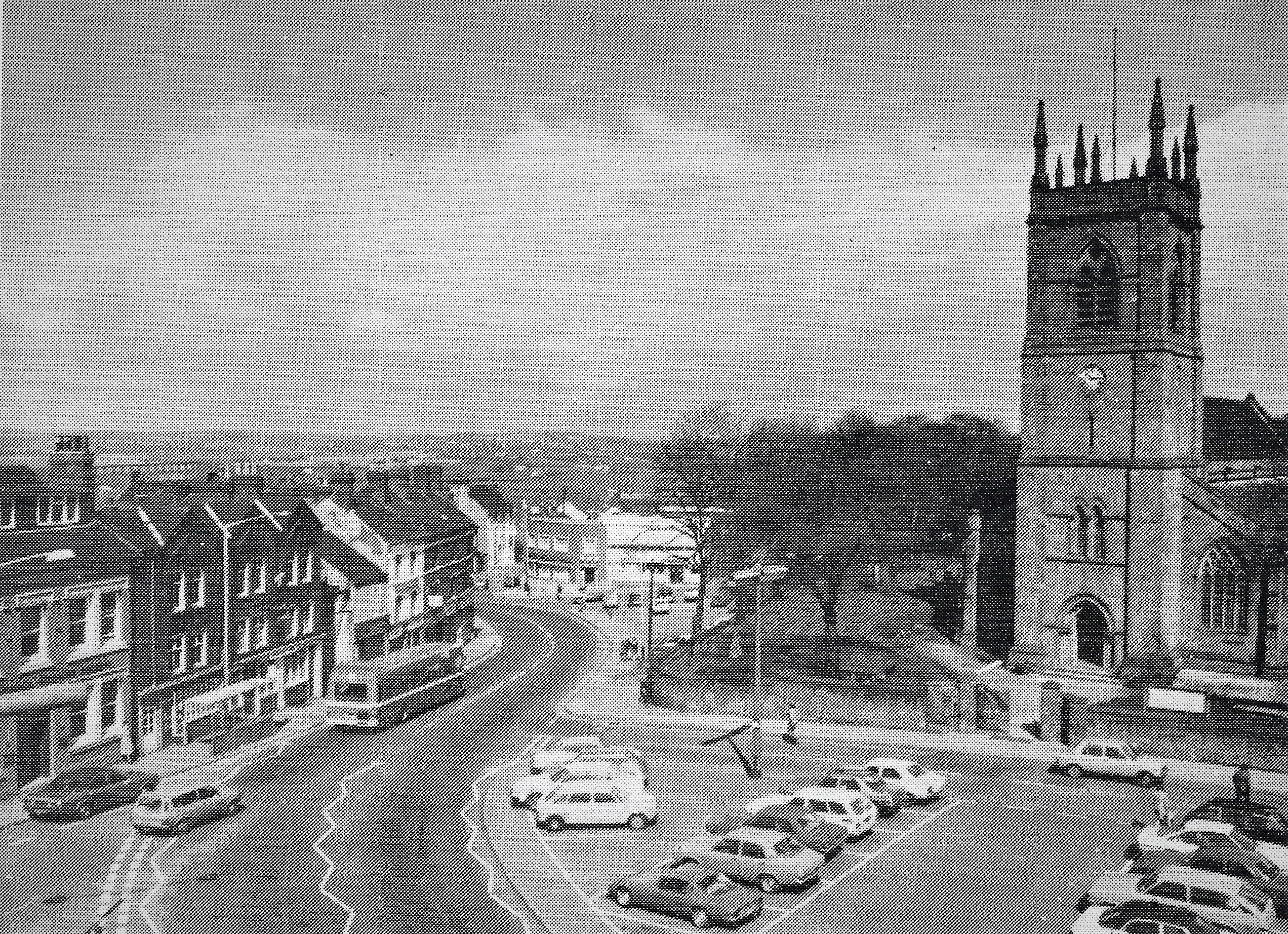

The Market Place in 1980

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Before we move on, into South Street, we can take a lengthy pause and consider how the town was locally governed, after the demise of the Local Board in 1887. Adeline doesn’t have much to write about the Town Council, which took over the responsibility of managing the affairs of Ilkeston — this is because she had several years ago, left the town for and had subsequently married.

So let’s walk into the Town Hall, behind us, and see what is happening there. What are the Councillors up to ?

Or, if you are not interested in local politics, then are you ready to wander down the west side of South Street ?