Also in ‘quiet South Street’, Adeline recalls that “the next shop was a chemist’s and druggist, kept by Mr. Richard Potts. It was also the General Post Office.”

This was 64 South Street and ‘the name of ‘Potts’ was to be seen in bold characters over the post office, as it is today’ (a resident, Pioneer 1900) … number 4 in the photo below, taken in 1897 (the Queen’s Jubilee celebration). In the later half of the 1840’s this was the shop of Frederick Daft & Co, grocer and draper, but was then occupied by the Potts family in 1851.

Also in this photo, we see John Mellor‘s butcher’s shop (2), the National Schools’ headmaster’s cottage (3), an alleyway leading to Ball’s Yard (5), a series of shops (6), and the Wesleyan Methodist Sunday Schoolrooms (7)

———————————————————————————————————————————

When Richard Smith Potts left Milton Street in Hockley in Nottingham he brought his wife, Mary (nee Singlehurst), and most but not all of his surviving children with him to Ilkeston. Those left behind and therefore probably unknown to Adeline included…

— the eldest child John who in May 1854 married Mary Ann North, eldest daughter of fishmonger Henry and Mary (nee Davis). He lived the rest of his life in Nottingham where at various times he traded as a currier, licensed victualler and a fish and game salesman.

— the second child Thomas, an under-guard on the Mansfield branch of the Midland Railway, who also remained at Nottingham and died there, aged 20, on April 9th 1853 “from injuries received whilst engaged in his duties at the railway station”.

In the station yard Thomas was assisting in attaching carriages to a shunting train engine and jumped onto the buffers of one carriage as the train made its way to another part of the yard. It appears that he slipped from the buffers and was run over by two of the following carriages. Terribly injured on his legs, abdomen, and right arm, Thomas was taken to the Nottingham General Hospital where he died shortly afterwards.

At the inquest into the death, the accident was entirely blamed on Thomas’s incautious behaviour.

— Mary who was the eldest daughter, born in 1834. She remained in Nottingham until in the 1850’s moved to Lancashire to live with her Singlehurst relatives in the Garston area.

— Shortly after arriving in Ilkeston, the youngest son Robert died in November 1854 aged three.

The Post Office.

Ilkeston Post Office was established in mid-1841, and for which the people of Ilkeston had to pay £42 annually plus whatever the letters, parcels, etc. would cost. In 1843 the annual ‘guarantee’ of £42 was rescinded by the postmaster-general, such that Ilkeston post office now operated like any other in the country. Money orders could now be obtained there though not, as yet, postage stamps !! The postmaster didn’t keep them, and the town’s booksellers couldn’t make a profit from their sale.

Paul Walker was appointed post master. At his death in 1851 the position passed to John Wombell.

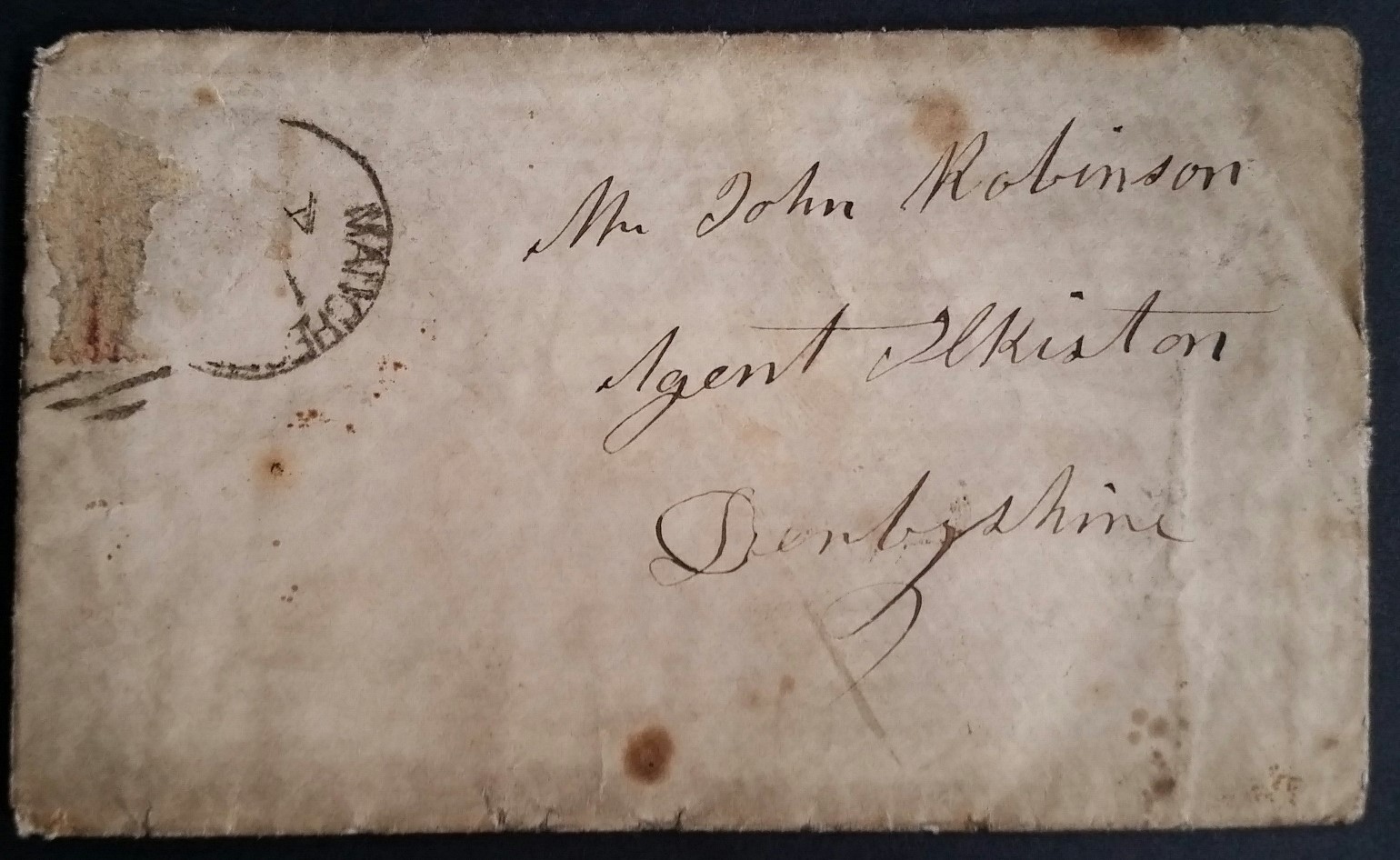

From his personal collection, Andrew Knighton found this envelope, “containing letter addressed to John Robinson (my great great great grandfather), mine agent, Ilkeston, with a postal cancellation of 13th April 1859”

In 1858 there was a ‘Post Office’ in Bath Street …was this just a post box ? It is mentioned in the Ilkeston Pioneer as being situated “two doors below the shop of Isaac Gregory, near the Queen’s Head Inn”. It was opposite the premises (Somerset House) occupied by the Tapley family in July of 1858.

And it was in September 1859 that Richard Smith Potts was appointed as sub-postmaster of Ilkeston but not without some controversy.

Initially the position had gone to lace manufacturer Alfred Sudbury of Anchor Row and this had incensed the Pioneer as well as several prominent Ilkeston tradesmen. Alfred’s appointment was severely criticised because, it was claimed, he could not read and write and was thus unable to perform his duties….. poor Alfred had to read — if he could — that the newspaper regarded him as “notoriously deficient in every necessary qualification as postmaster for 10,000 inhabitants”.

What further inflamed the Pioneer was that ‘political jobbery’ was evident in the appointment. The lacemaker had been nominated and appointed through the influence of his Liberal and Whig cronies.

The subsequent campaign to nullify the original choice was successful and Richard Smith Potts was chosen to replace Alfred.

And what relief the Pioneer felt !!

“All classes of society will agree that a more suitable person (than Mr. Potts) could not be found: his well-known promptitude and business habits are a sufficient guarantee that the interests of the public will not be neglected in his hands”.

Criticism of postal services and deliveries is not a 21st century phenomenon.

Sheddie Kyme described the General Post Office as a ‘standing disgrace to the town’. He had seen ‘better accommodation provided in this respect in very small villages’. The people of Ilkeston had put up with this situation for many years and perhaps the small size of Mr. Potts’ shop reflected ‘the business capacity at this time’.

The Ilkeston Advertiser described it thus …

“The shop is not large, one side of it is occupied by drugs, the other by groceries, and at the end of the passage betwixt the two sets of goods in which the proprietor deals is a small window or hole, opening on to a small desk, where Her Majesty’s agent receives telegrams and deposits, distributes stamps and affords information”. (IA 1881

Sheddie Kyme also records the names of two postmen both of whom “were familiar figures in town, and what they did not know in the matter of news concerning the town and district, was not worth knowing”.

— John Tomlinson of Rutland Street was born in Stapleford in 1819 and worked as a shoemaker in Shardlow. There he married Rosetta Gilbert, daughter of Thomas and Jane (nee Shardlow) in 1847 and moved to Ilkeston about 1854. He traded here as a cordwainer but was also a letter carrier and newsagent of 4 Rutland Street. Sheddie Kyme also recalls him as a lamplighter.

“Those who remember Mr. Tomlinson will doubtless recall his shuffling gait, his short walking stick, and his manner of looking at you over the top of his spectacles”.

— Henry Harrison of Nottingham Road, and later of Market Street where he died in 1903. Born in 1827 he was the son of framework knitter Joseph and Elizabeth (nee Stables) and from about 1869 his occupation was recorded as ‘postman’. In February 1887 — perhaps in icy or snowy conditions ? — Henry slipped off the pavement and broke his leg in two places.

In 1863 the Pioneer was quietly outraged that the Postal authorities had made alterations to the collection and delivery of post without any prior warning for the public. Letters now arrived in Ilkeston on the eight o’clock morning train which of course was generally 10 to 15 minutes late, meaning that deliveries would not begin much before nine in the morning, two hours later than previously. Evening despatches of letters to the ‘North’ were now at 5.15 instead of 7pm as before, though the despatch to the ‘South’ was now at 8.15.

“In these days of improvement and reform, we look not for retrogressive measures from the post-office. We expect, therefore, that very soon the public will embody their complaints in a memorial to the Postmaster-General; and it is hoped that the officious officials who have curtailed our postal advantages will soon be taught how to improve upon the system they have just initiated and imposed upon this town”.

In August 1867 Post Office deliveries were now to begin at 7am and not 8.30am as before.

“This will be a great advantage to the public” (IP)

Two months later and the Post Office Surveyor was asking all correspondents to address their letters and other items to ‘Ilkeston’ and not to ‘Ilkeston, near Nottingham’ as the latter was confusing the sorting officers.

Mail was being misdirected and thus arriving late at its true destination.

On August 1st 1873. by order of the Post Master General:

“With the view of diminishing the temptations to which servants of the Post Office are exposed by the practice of sending articles of value in unregistered letters, and in order to give greater security to correspondence of that class, the regulations respecting letters containing coin will be extended to all inland letters and packets not tendered for registration which unquestionably contain any of the following articles, viz, banknotes, postage stamps, jewelry,(sic) and watches. Any such letters or packets will, therefore, be subject to a double registration fee of 8d”.

In 1877 Richard Smith Potts retired as postmaster, the role taken up by his son Charles.

In 1878 a general afternoon delivery of letters to Ilkeston replaced the previous much-restricted one.

Also two additional letter boxes were placed at the premises of shopkeeper Frederick North Tummon of Gallows Inn and grocer William Skeavington of Church Street, Cotmanhay. This saved residents of those areas a walk of about a mile to post their letters.

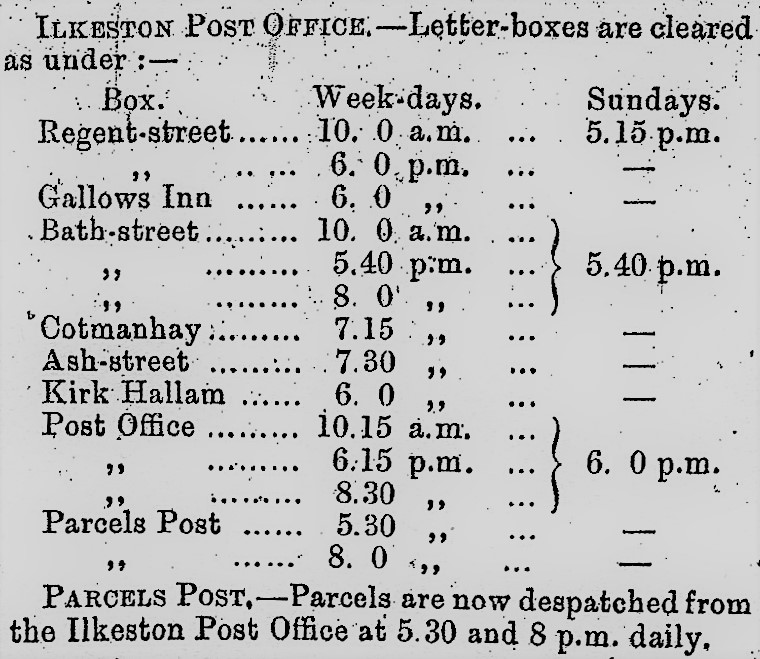

And when could you expect them to be collected ?? … up to three times a day, and a Sunday collection !! (1884)

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Potts family.

Adeline tells us that “”when Mr. R. Potts retired, he went to live in Robin Hood’s Chase, Nottingham”.

Richard Smith Potts and his wife Mary left Ilkeston for Nottingham in the early 1880’s.

Mary died at Berkeley Villas, Robin Hood’s Chase, on January 21st, 1883, aged 73.

Richard Smith Potts died at 82 Robin Hood’s Chase on July 17th, 1890, aged 83.

“The Potts family consisted of two sons”.

“Smith, the eldest was a chemist, and left Ilkeston when a young man”.

Son Smith was younger than brother Charles and initially assisted his father at South Street while serving as a pupil teacher at the NationalSchool.

Old Resident recalls him joining the 16th Regiment Volunteer Rifle Corps about 1860, when he would be about 16.

Smith was “full of it and so bubbling over with enthusiasm that he must needs put us lads through our facings in the school. That was my first experience of soldering”.

The same writer recalled an incident about 1861 when he was about nine or ten years of age.

“Young as I was, I also served as a monitor for some months, for which my remuneration was 1s 2d per week, out of which 2d was deducted for my ‘school wage’. Some time before I left I was injudicious enough to tell the boy who sat next me in the first class that I could write as well as the teacher. The information was duly communicated to Smith Potts, who was in charge of the class. In my mind’s eye I can see at the present moment the disdainful curl of his lips as he wrote in my copy-book, ‘the great boasters are little doers’.

“ I had to fill the whole page with that text, and I believe it taught me a salutary lesson”.

In the 1870’s Smith left for London.

Mystery alert!

Smith appears on the 1881 census as an accountant’s clerk in Hackney, London with his ‘wife’ Margate-born Marion, although there doesn’t appear to be a marriage for him before that date.

Ten years later and he is still in London as a law solicitor’s clerk, but now is single.

Another ten years pass and Smith is in East Ham, a china and glass commercial traveller, living with spinster Edith Britton the Elder and her two illegitimate children, Harry aged seven and Edith the Younger, aged two.

Edith the Elder was the illegitimate daughter of Emma Britton who was the illegitimate daughter of Eliza Britton, all three born in Nottingham.

The 1911 census finds Smith Potts still in East Ham as a commercial traveller, with ‘wife’ Edith and children Harry and Edith Potts, and showing that they married about 1892. Again there appears to be no record of this marriage.

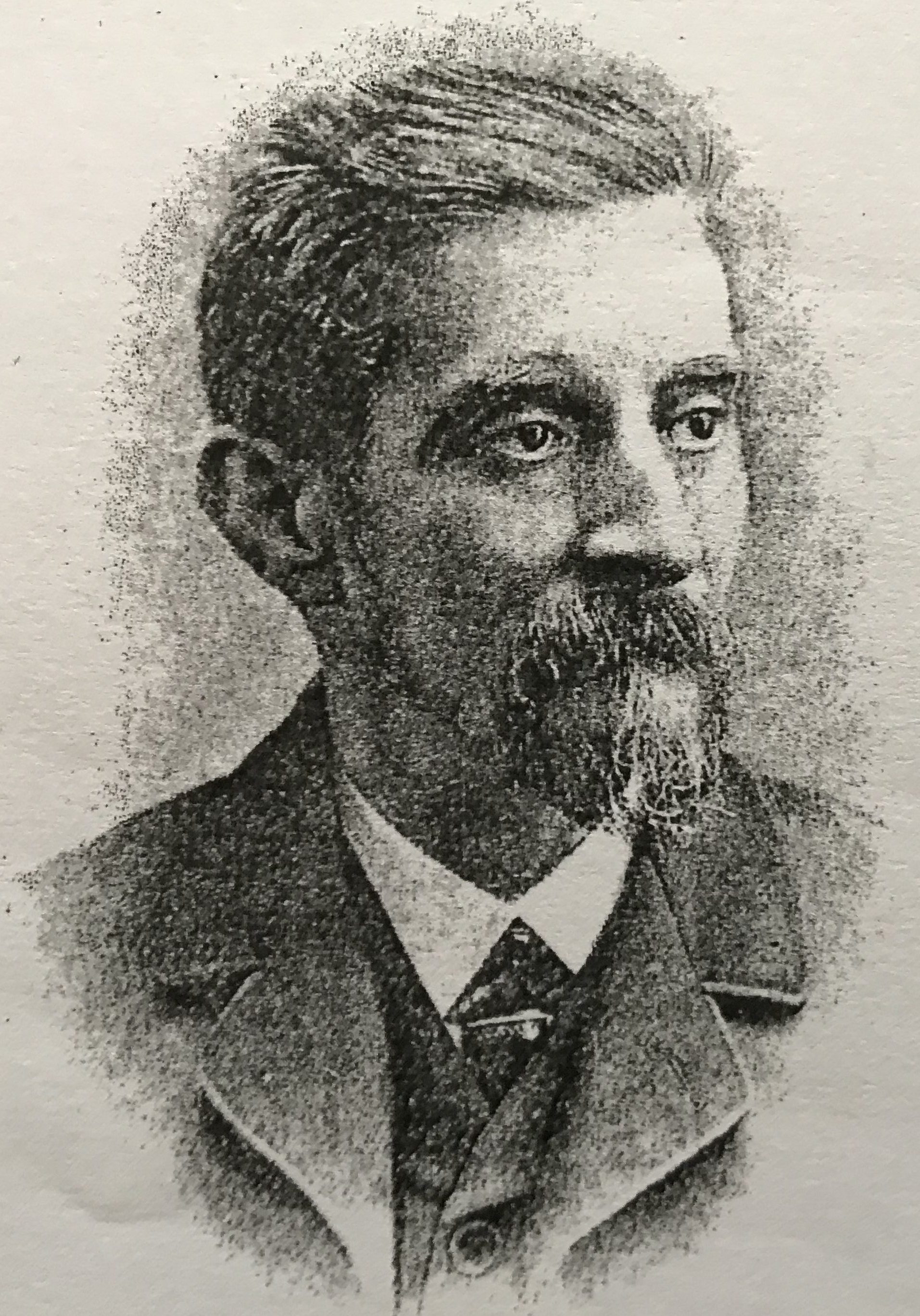

“Charles was also a chemist. He started in business, in a new shop at the bottom of Bath Street”.

Born at Nottingham in April 1842, Smith’s brother Charles also learned the druggist trade with his father before establishing himself, first at Pimlico and then in his chemist shop at the corner of Granby Street and Bath Street, which he opened in May 1872.

By 1879 he was describing himself as a ‘Homoeopathic Chemist’, and in the early 1880’s he moved to trade in Bath Street

In February 1870 he had married Amy Henshaw, eldest child of William and Sarah (nee Aldred). William had been the landlord of the Rose and Crown Inn at Cotmanhay, along with his father-in-law Joseph Aldred.

Charles became postmaster on the retirement of his father in April 1877 by which time his father had been in the business for 26 years.

In September 1882 Charles applied for three licences… a wine, a spirits, and on ‘off’ licence. He argued that the latter licence would enable him to sell better quality beer than could be found in many of the local public houses. Many brewers had recently been buying public houses to help them establish a monopoly and then sell inferior beer. The ‘off’ licence however was the only one refused as there were several public houses near to Charles’s shop.

So in the following month, Charles returned to ‘what he knew best’ ? … and in the Pioneer was advertising his post-office work …. Emigration, Shipping, and Forwarding Agent for the United States, Canada, Cape, Australia and Zealand, and all other parts of the world. Assisted passages are granted to Canada — Farm labourers, £5; Female Domestic Servants, £4. Every information given free of charge.

By the late 1880’s Charles was at 166/168 Bath Street (see photo below). He was described as a dispensing and family chemist, tea merchant, shipping and retail tobacconist, wine and spirit merchant, and a shipping and emigration agent for settlers in America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and The Cape booking the best lines at the lowest charges … and of course, he was also Postmaster of Ilkeston. His three storied premises had a frontage of over 50 feet (very generous indeed !!) and housed a very large stock of goods

In September 1887 the Market Place Post Office used by Charles was put up for auction; it was the copyhold property of the Manor of Ilkeston, Charles bought it for £820 !!

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

“There were four or five daughters. One assisted Miss Hannah Horridge in her dressmaking business. Jane and Kate, the two youngest, managed the Post Office.

The daughters were Susannah, Elizabeth, Hannah Jane and Kate, the last one being the only child born in Ilkeston, in 1852. It was Susannah who helped Miss Hannah Horridge until she married William Joseph Raven in June 1877. Elizabeth worked with her father in the shop. Hannah Jane remained unmarried.

“Kate, I believe, was the only one of the daughters to be married. She married William Smith, eldest son of Mr. William Smith, draper, Market Place”.

Kate had married in September 1876 and after the birth of daughter Ethel Beatrice in 1878 moved to Beeston for a time with her tobacconist husband, William Harding Smith, son of Market Place draper William and Elizabeth (nee Harding).

The family later returned to Ilkeston.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Charles Potts died on Tuesday morning, September 24th 1902, at his Bath Street home, aged 60. The burial ceremony, at Park Cemetery, was attended by postmen in uniform, Post Office officials, employees, Council members, members of the Church Institute, Masonic brethren, and members of the Basford Board of Guardians. The wine and spirit dealership was transferred to Amy Potts, widow of Charles, along with the chemist and druggist shop at the bottom of Bath Street.

The Potts shop is on the extreme right, opposite the Rutland Arms Hotel

The shop of Charles Potts was at 166 and 168 Bath Street.

To help you get your bearings, here is the site of the two premises in 1959.

Opposite the Rutland Hotel, and situated between Rutland Street to the north and the redundant Town Station to the south.

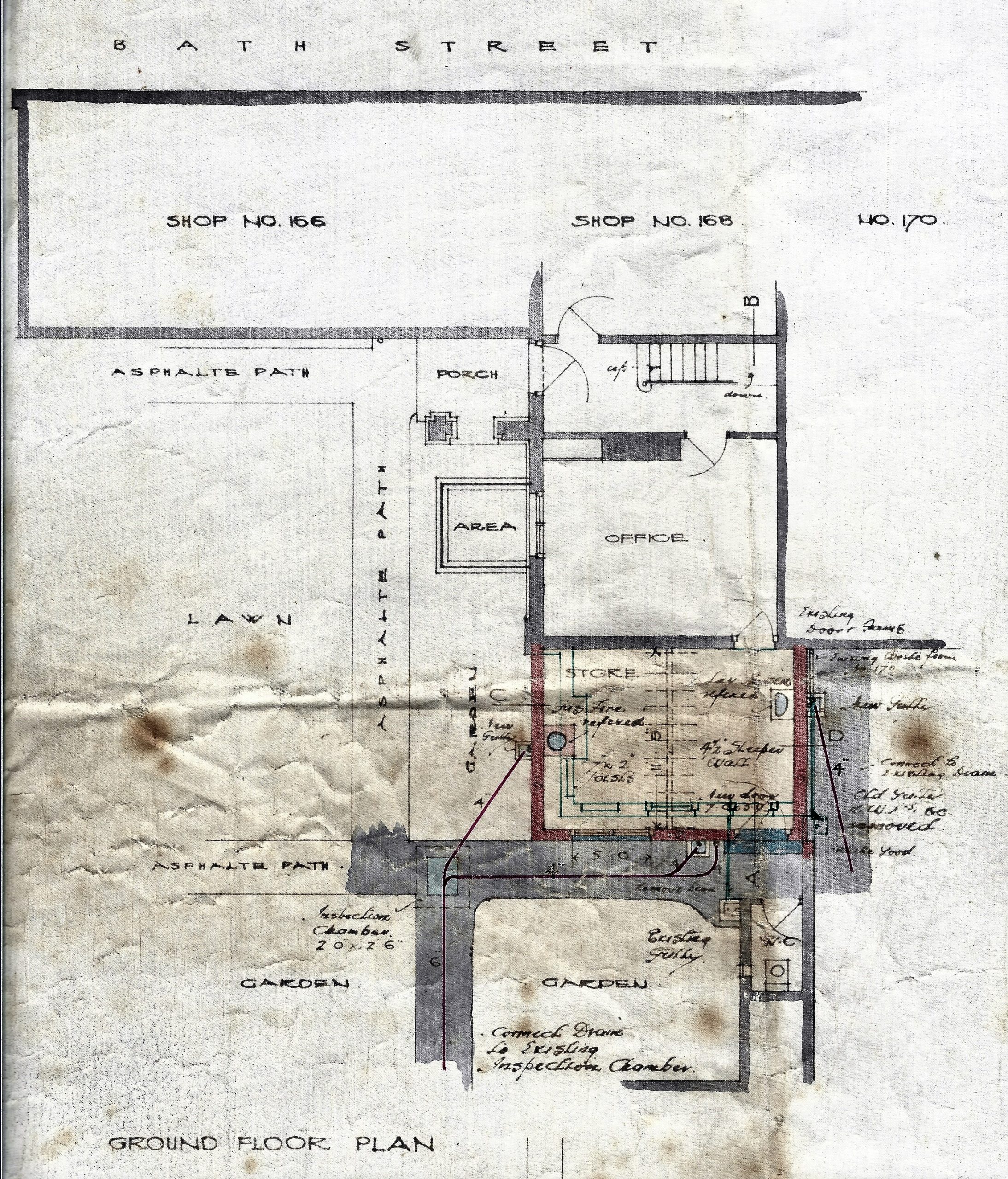

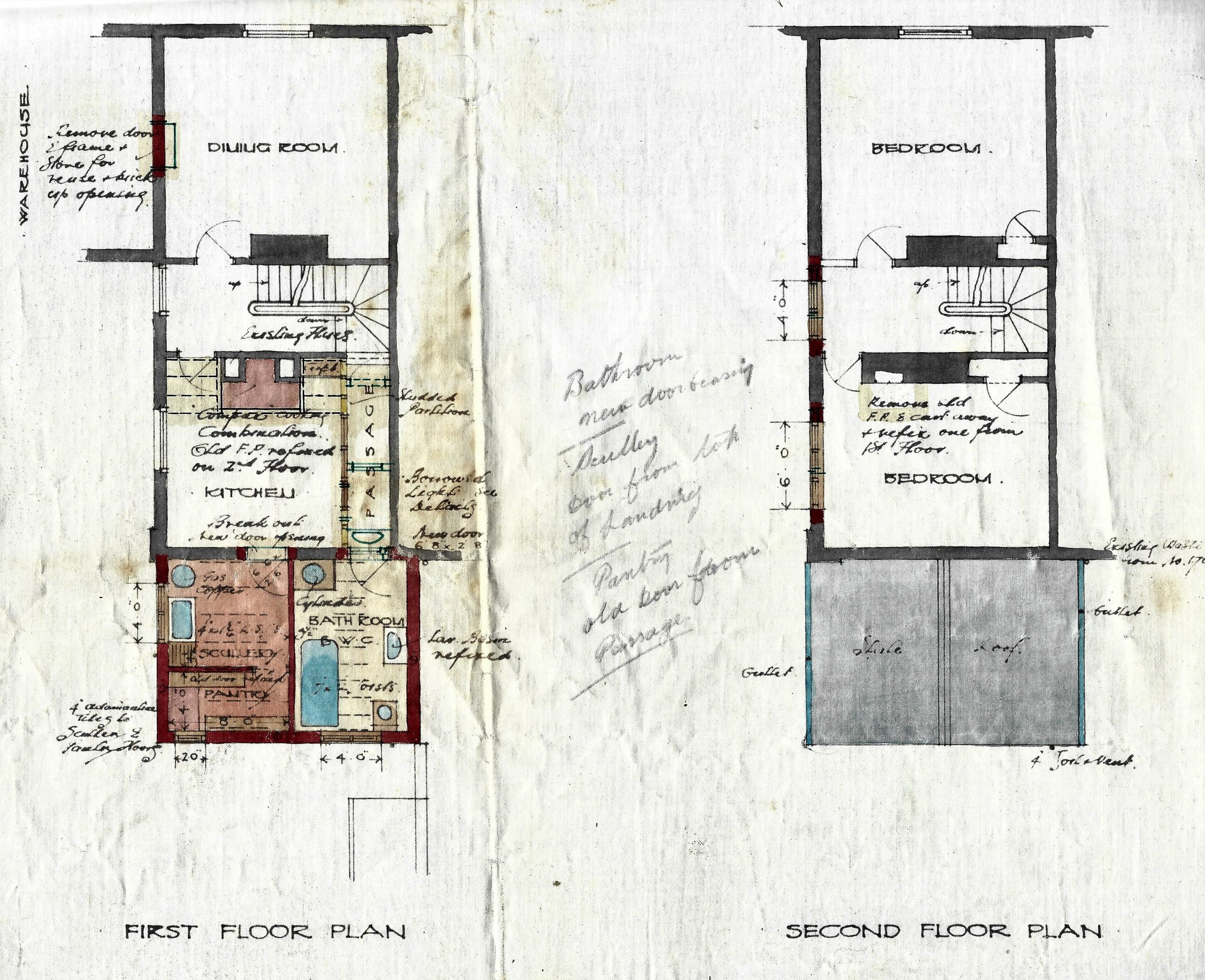

In 1925 the executors of the late Charles Potts proposed alterations to the rear of the Bath Street shop premises, and plans were drawn up by Frank Hobson, an architect and surveyor of 158 Bath Street. Parts of them can be seen below; you will probably find it difficult to distinguish what changes were proposed but I have included the drawings so that you might form an impression of the interior of the property. (Try to ignore the stain … old age !!). Note that Bath Street is at the top of each plan.

Dated February 1925 (from Jim Beardsley’s document collection)

Born in 1900, architect/surveyor Frank Hobson was the only surviving son of Frank and Sarah (nee Flinders) and could trace his Ilkeston ancestors back to Matthew Hobson (his grandfather of Field House) and Benjamin Flinders (his great grandfather of the White Cow beerhouse). He was living at 158 Bath Street with his parents but was articled to Messrs. Starr and Hall of Nottingham. (Frank was first cousin once removed to one of the partners, Edwin Benjamin Holmes Hall).

Shortly after midnight on September 1st, 1935, Frank was riding his motor-cycle combination along Derby Road in Stapleford when he was in collision with an unattended, horse-drawn night-soil cart. He was very badly injured (compound fracture of the leg and fractured arm), immediately taken to Nottingham General Hospital, but died shortly after.

Although the cart had warning lights on it, the driver (and by extension, his employer the Rural District Council), was admonished at the inquest for leaving the cart unattended on a main road.

Frank was buried in Park Cemetery, Ilkeston, on September 4th.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Charles and Amy Potts at rest, Park Cemetery.

After the cross, the urn is one of the most commonly used cemetery monuments. The design represents a funeral urn and is thought to symbolize immortality.

Cremation was an early form of preparing the dead for burial. In some periods, especially classical times, it was more common than burial. The shape of the container in which the ashes were placed may have taken the form of a simple box or a marble vase, but no matter what it looked like it was called an “urn,” derived from the Latin uro, meaning “to burn.”

As burial became a more common practice, the urn continued to be closely associated with death. The urn is commonly believed to testify to the death of the body and the dust into which the dead body will change, while the spirit of the departed eternally rests with God.

The cloth draping the urn symbolically guarded the ashes. The shroud-draped urn is believed by some to mean that the soul has departed the shrouded body for its trip to heaven. Others say that the drape signifies the last partition between life and death.

From ThoughtCo.com …. an article by Kimberly Powell (https://www.thoughtco.com/photo-gallery-of-cemetery-symbolism-4123061)

Ball’s Yard came next.