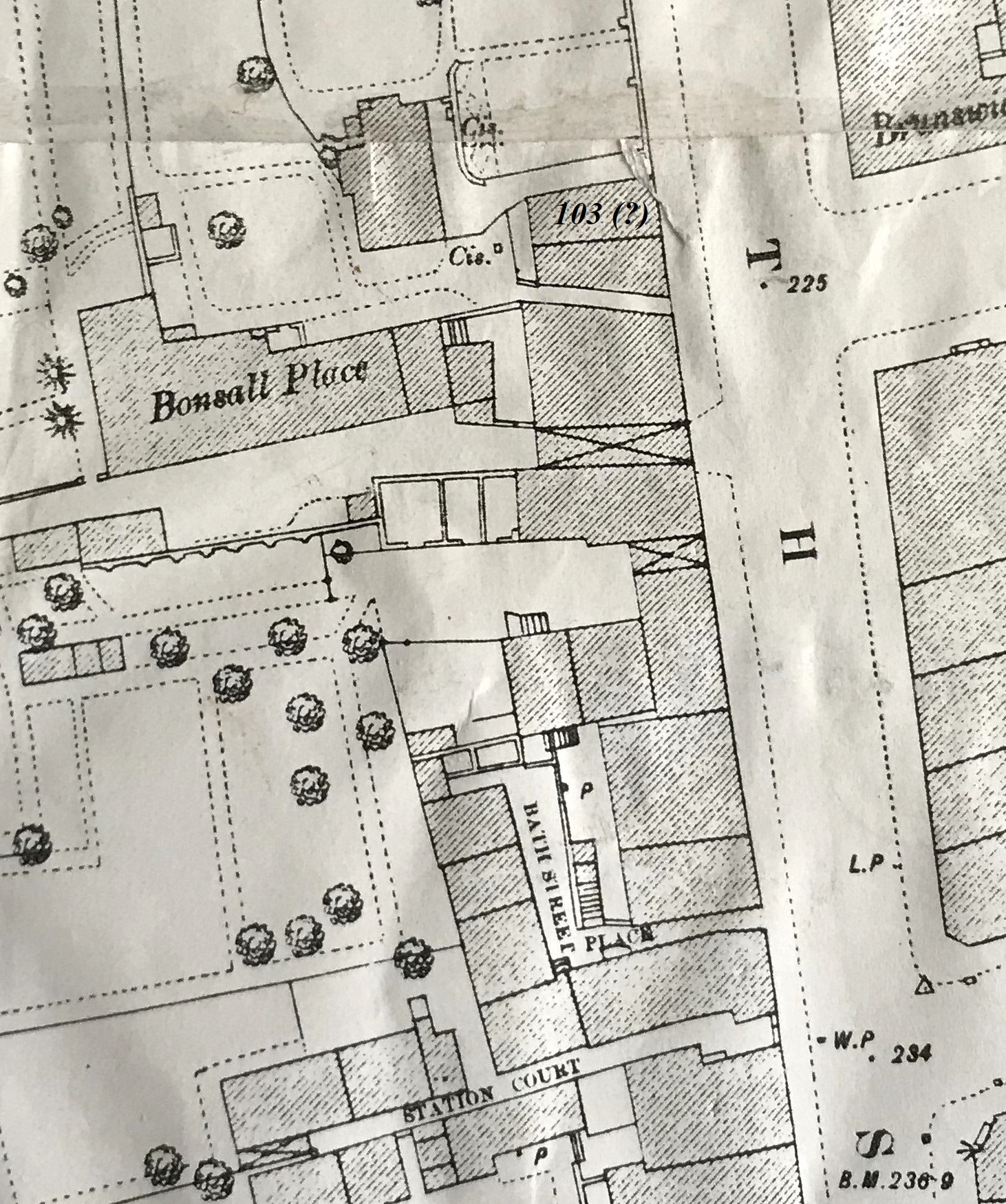

We walk on down Bath Street and come to Adcock’s Yard (later renamed Bonsall Place)

Walking north, down Bath Street towards Cotmanhay, the entrance to Adcock’s Yard (Bonsall Place) is on the left. Opposite, on the other side of Bath Street, are the Wooliscroft premises at the corner of Wilton Place.

Just off the top of the map is the Poplar Inn which we will come to shortly.

“In (Adcock’s Yard) were two houses. Sydney Adcock lived in one. (His brother at one time lived in the other)” … Adeline remembers.

Adcock’s Yard was home to Ticknall-born framework knitter John Adcock senior and his wife Ann (nee Bark) who were married in March 1823 and who had several sons ….John junior (1832), Thomas Bark (1837), Samuel (1838), George (1842)….. but no Sydney.

The property had been owned by Thomas Barke, the father of Ann Adcock.

On the 1841 and 1851 censuses it was occupied by the widow of Thomas, Ann (nee Maddock) and when she died in October 1851, she willed it to her daughter Ann.

John Adcock senior died in Ilkeston from bronchitis in February 1864, aged 64. It was wife Ann (nee Bark) who sold it at the end of 1866.

“At his death the property was sold to Mr. William (should be James?) Bonsall, pit contractor …. and I remember that the occupants did not want to leave the houses, and force had to be used to get them out.”

The origin of the property dispute mentioned by Adeline arose in December 1866 when contractor James Bonsall, then living in Queen Street, bought the properties in Adcock’s Yard at public auction. He acquired the title deeds but did not take immediate possession of the premises, and paid Ann Adcock, John’s widow, £5 to vacate her house — or so he said.

Ann’s sons, Thomas and John junior, disputed the legality of the sale, and with their brother-in-law, journeyman joiner William Cragg – who had married Emma Adcock in May of 1865 — they decided to squat in some of the yard’s houses. This required a little bit of ‘breaking and entering’.

Contractor James Bonsall was having none of this, obtained a warrant for ‘the forcible ejectment’ of the squatters and prosecuted them at Ilkeston Petty Sessions in November 1867.

The accused trio initially pleaded ‘not guilty’, though James was in a forgiving mood — he would not pursue his prosecution if they would ‘deliver up peaceable possession’ to him.

This offer was rejected at which point the magistrates emphasised the serious nature of the offence and threatened committal to trial. This was adjourned for a fortnight, perhaps to allow some sober reflection, while the police were ordered to execute the warrant.

In late November 1867 Ann Adcock felt compelled to write to the Pioneer …

“I beg to deny the statement … made by or on behalf of James Bonsall, of Ilkeston, saying that he had paid me £5 to leave the property. I have never received any money whatever, not even five pence, from him”. So there!!

Despite Ann’s resolute opposition, the dispute was settled in James’s favour. The Adcocks moved out and the Bonsalls moved in .. and the yard was ‘rechristened’ Bonsall’s Yard.

James Bonsall enfranchised the property in December 1867.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

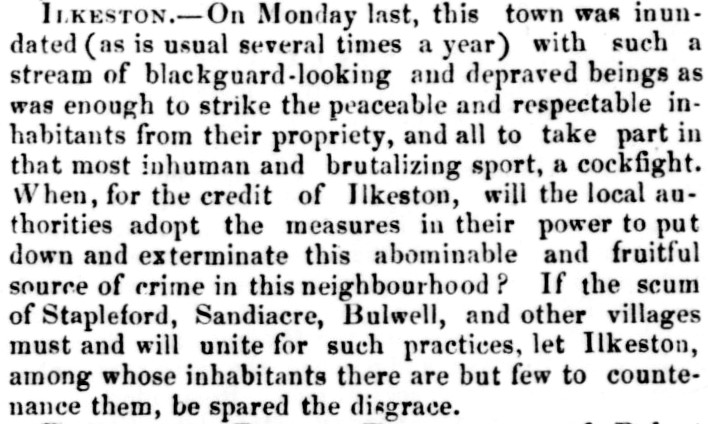

Again, Adeline writes that “Sydney Adcock was a noted cockfighter”.

As we can see from the article in the Derbyshire and Chesterfield Reporter (left: May 19th, 1831) not everyone in Ilkeston accepted the need for cock fighting.

Following this, the Cruelty to Animals Acts of 1835 and 1849 outlawed cock-fighting but despite fines it did persist, especially in coal-mining areas.

Thus, under the heading of “Cocking – Town against County of Derby”, the Nottinghamshire Guardian (August 1850) reported on ‘battles’ held at Sidney’s Cockpit in Ilkeston.

This was the third in a series of such contests held between the breeders of Town who pitted ‘duns and birchins’ against the County who brought mostly ‘pyles’. (All types of fighting cocks).

In this particular contest there were nine battles in the ‘main’ (match) and ‘heavy sums’ of money changed hands.

The County won by one battle.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

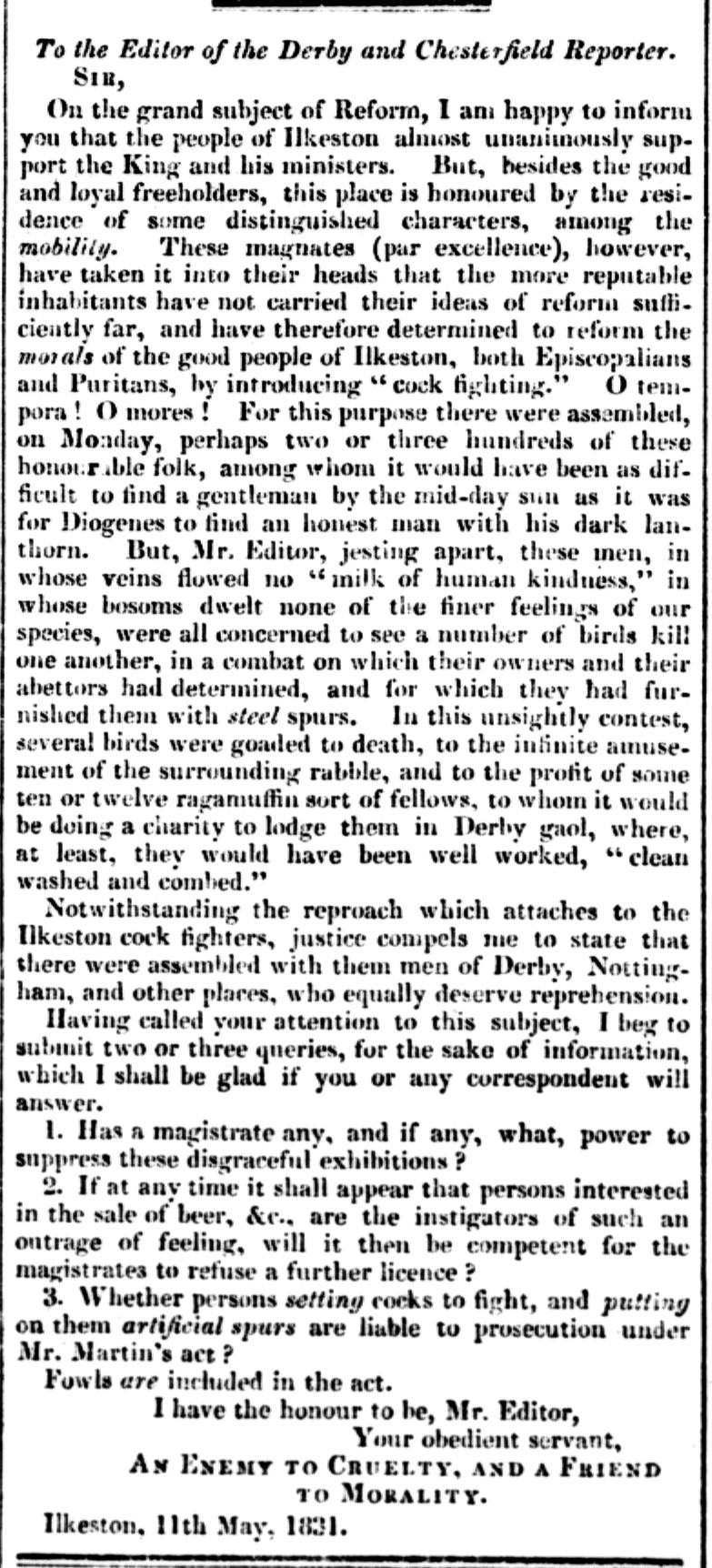

Ben Caunt (1815-1861) … Heavyweight Champion of England

John Cartwright recalled a meeting with Big Ben Caunt, bare-knuckle Champion of England of the late 1830’s and early 1840’s, when the latter had cause to leap over John who was playing ‘ring taw’ — a marbles game — on the Bath Street footpath with his friend Henry McDonald.

“I gazed on that fine muscular form and on the scarred features, and the picture has never been erased from my memory”.

Not surprising! How often is it that a champion of England — ex or otherwise — plays leap-frog with a lad as he plays with his mate?

John goes on to say that Ben was considered a fair fighter, one who would not take a mean advantage of his opponent. “His equally noted competitor for boxing honours, William Thompson or ‘Bendigo’, was always considered ‘tricky’ and was no favourite Ilkeston way”. At the time John saw him ‘Big Ben’ was on his way down Bath Street to witness a cockfight at Adcock’s public house.

He was a big man with a big chest, a booming voice and an international career in bare-knuckle boxing. ‘Big Ben’ Caunt’s name has lived on since he was finally laid out, in St. Mary Magdalene’s churchyard.

Born in nearby Newstead, he grew up in Hucknall. His first recorded knockout was one of his own relatives in 1835. Once spotted, his reputation, like him, just grew and grew. By the age of 19 he stood 6ft, 2 1/2” (1.89m) tall and weighed 14st 7lbs (92kg).

He found fame and a close rival from nearby Nottingham, Bendigo William Thompson. Like Ali and Frasier in the 20th century, ‘Big Ben’ and Bendigo would meet three times and share the title between them. But for Ben there were no gloves and no time limit; and each meeting was a ding-dong battle. Their first bout in 1836 lasted 22 rounds with Bendigo the winner, ‘Big Ben’ got his revenge in 1838 but this time it took 76 rounds; finally losing in 1845 over 96 rounds.

In between these grudge matches ‘Big Ben’ defended his title in London and toured the USA. In retirement he became a pub landlord in London. Towards the end of his life, tragedy struck when a fire at the pub claimed the lives of his two children. Martha and Cornelius now rest with Ben in the north side of the churchyard.

His fame was such that ‘Big Ben’ became a by-word for anything big and loud. One possible origin for the name of the most famous chiming bell in the world. When Big Ben strikes it recalls ‘Big Ben’ in his pub calling ‘Time’.

You can find out more about Ben in church and visit his grave which sits in the shadow of the north transept.

taken from Hucknall St Mary Magdalene Parish Church site.

As far as ‘Bendy’ Bendigo was concerned, “In after years he turned preacher, and held forth occasionally at the Gospel Hall in Derby” (John Cartwright)

A typical bare knuckle fight where any tactic was allowed. This illustration, from ex-booth boxer Dick Johnson’s 1987 book Bare Fist Fighters, represents one of the fights between local heroes Bendigo and Ben Caunt

In January 1885, the Globe newspaper (and many others) reported on a prize fight at Mapperley near Nottingham, between Samuel Hickman of Bulwell, and Thomas Brewin of Ilkeston. The former was a 50-year-old, 14-stone, seasoned pugilist while Thomas, aged 31 and weighing two stones less, was making his début. The fight took place before an audience of about 30 spectators, lasted 28 rounds and about one hour — “both were severely punished” and Thomas emerged victorious when Samuel ‘threw up the sponge’. This is how most reports viewed the result though the Sportsman wrote that the veteran had been declared the winner !!

P.S. There was no interference on the part of the police.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Various directories from 1842 to 1850 list an unnamed beerhouse in Bath Street run by John Adcock.

Was this Sydney ?

The Nottinghamshire Guardian reported in January 1874 that Sydney Adcock of Crichley Street was working as a ‘holer’ at one of the pits owned by Messrs. Barber and Walker near Shipley Gate Station, Eastwood when a quantity of coal fell on his head and upper body.

He was dead almost immediately and ‘five children’ were left orphaned as a consequence.

This was in fact collier John Adcock junior who died of a fractured skull caused by a fall of coal on January 12th 1874.

He had married Olive Clark in 1858, spent some time thereafter in Hoyland, Yorkshire, before returning to live in Crichley Street in the late 1860’s.

Olive died in Crichley Street in January 1873, a few days after giving birth to their daughter Olive Clark Adcock, who then died three months later.

The Ilkeston Telegraph reported that six children were left orphaned when John junior died — I believe that there may have been only four.

One of the orphaned children was son John Adcock the third, born in 1865 at Hoyland near Barnsley. Like his father he too died in a colliery accident — in September 1898 — when a roof at Trowell Moor Colliery collapsed onto him. He lived for about two weeks after the accident but died at Ilkeston Hospital on September 30th.

And thus Bonsall Place makes its appearance on the map of Ilkeston – opposite Wilton Place — when James Bonsall the pit contractor ‘annexed’ Adcock’s Yard in 1867.

James’s second wife Mary (nee Tooth) died at their Bath Street home in November 1885 – she was the half-sister of George Tooth, currier of Bath Street.

James Bonsall died at Bath House in Bath Street in December 1893 aged 75, at the home of his daughter Amelia who was by then married to baker and confectioner Thomas Adlington.

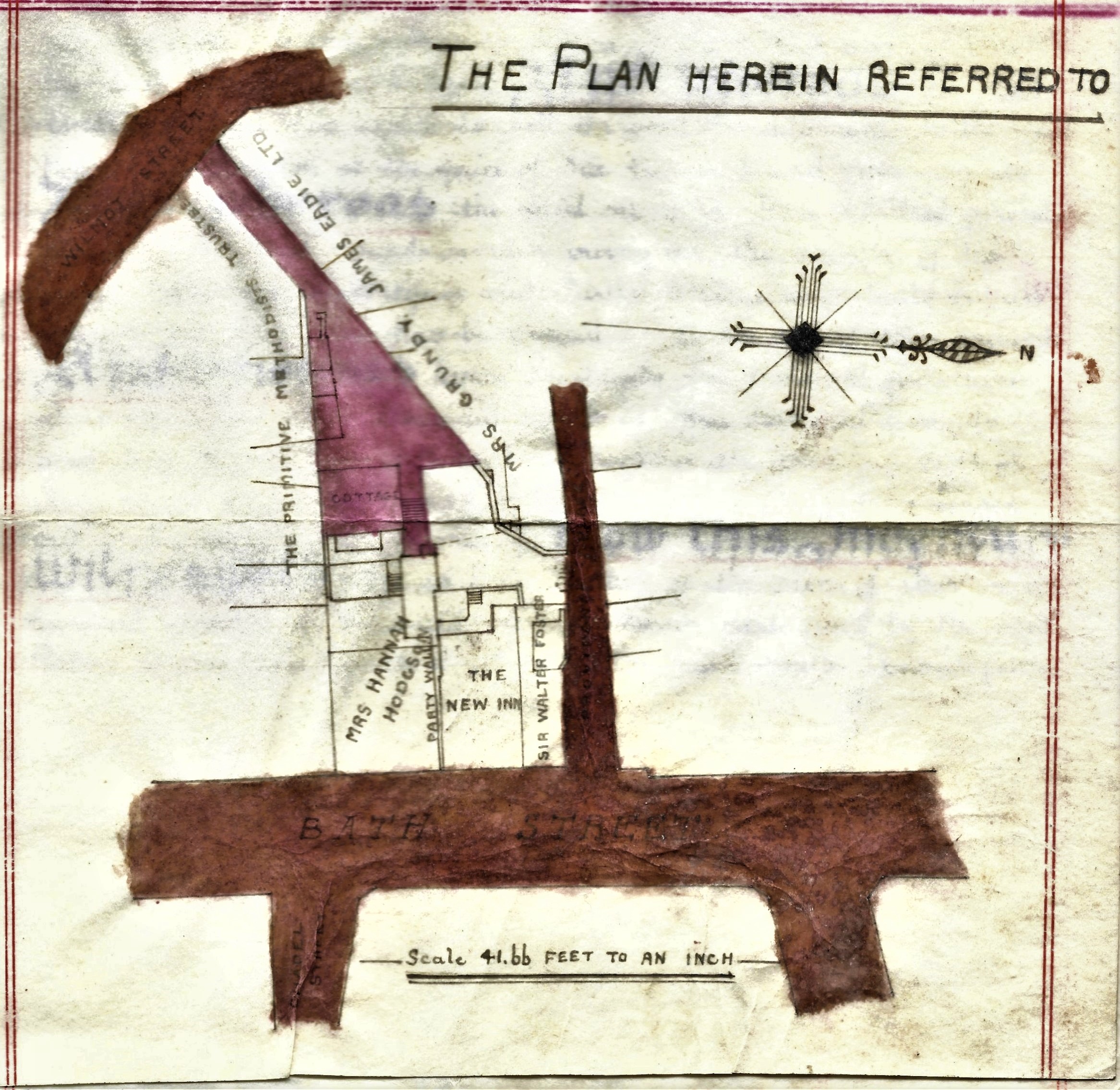

James had acquired the New Inn premises in 1873, and on his death in 1893 the inn was bequeathed to his son Walter, along with a cottage and property to the rear of the inn. Adjoining the same inn were three premises in Bath Street, also owned by James, which he left to his daughter Hannah, now the wife of Frederic Hodgson. All of this can be seen in the plan below which was attached to a Conveyance Agreement of February 4th 1899 (courtesy of the Jim Beardsley Archive)

You can find more detail of James’s other property here

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

My thanks to John Daykin for this press clip.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Isaac Field, tailor and draper

You can see No 103 Bath Street picked out on the map at the top. This was the number since the late 1880s when Bath Street premises had been been renumbered. The properties on the west side were now all odd numbers whereas they had previously been consecutive. On the east side they were, of course, now even numbers.

In 1894 number 103 was the shop of draper and tailor Isaac Field where a serious fire broke out on March 6th and where Isaac lost nearly all of his stock, either through the fire or the water damage.

Isaac had branched out on his own just a couple of years previously, having been employed as a draper’s assistant at the shop of Charles Woolliscroft. He had rented premises initially in Station Road but then moved into Bath Street, to take over 103 from Drs. Joseph Carroll and Leslie Fyfe Walker who were using the property as a surgery and dispensary. It was an old cottage property, owned by the doctor and adapted for the purposes of a shop. Built many years before, it was only two stories high, and Isaac used it as a lock-up, while he and his family lived in a Gregory Street villa. It had chamber floors made of plaster and this feature perhaps inhibited the fire from spreading.

As Wednesday was Early Closing, Isaac had secured the shop at one o’clock; about three o’clock Police Superintendent Daybell walked past, didn’t notice anything to alarm him and walked on, to the Mundy Arms. On arriving there he looked back and saw Bath Street engulfed in smoke, while the alarm had been raised. Headed as usual by Captain Henry Kilford, the Volunteer Fire Brigade was quickly on the scene, though the shop window had been blown out and fire had taken hold of the interior, setting the wooden staircase on fire, the heat smashing the upper floor windows. However within half an hour the Brigade had the fire under control, and had prevented it from seriously damaging the upper storey and from spreading into neighbouring premises. Poor Isaac had now lost most of his stock — thankfully for him it was insured (with Sun (Fire and Life), agent Arthur Cordon !!).

Very shortly after, the Field family left Ilkeston and on the 1901 Census can be found at Town Street in Sandiacre.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

As we walk northwards along Bath Street (just off the north of the above map) we come to a site associated with the influential Potter family of Ilkeston.