Adeline is very familiar with this area …. “Ball’s Yard with two cottages came next. The first private houses in South Street, on the west side were up Ball’s yard, at the side of the old Post Office. Here lived old Mrs. Ball.”

‘Old Mrs. Ball’ was born Frances West in 1789 at Bulwell, daughter of Edward and Mary (nee Richards) and wife of Thomas Ball, the brother of Francis Ball senior of Burr Lane. The couple married in April 1809.

Adeline continues …. “The next shop was a pork shop, fronting the street. This property was very old. It belonged to the Balls. The shop had been built in the bank, and a flight of stairs led up from the small shop to the house above. When Frances died, her son Adolphus (always called Dolf), went to live in the cottage”.

In 1842 Thomas Ball’s copyhold premises and the two adjoining properties, occupied by lacemaker William Sills and cooper Joseph Gregory, were owned by William Barker but were put up for sale in that year.

———————————————————————————————————————–

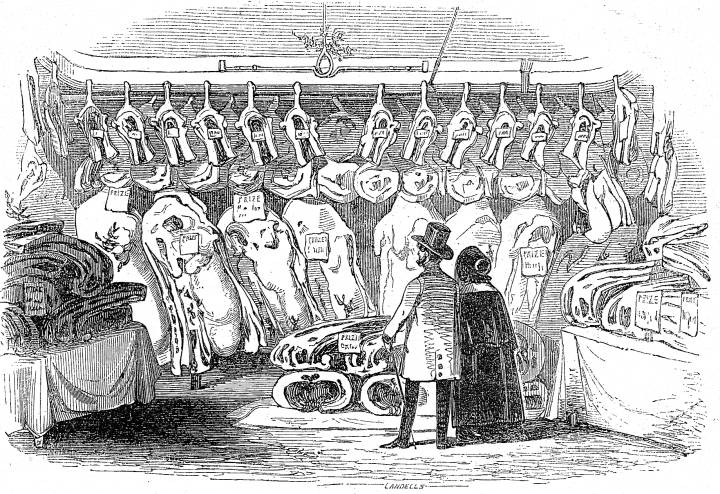

A Victorian butcher’s shop

Prize Meat at Christmas from the Illustrated London News (23 December 1843) … (https://victorianweb.org/periodicals/iln/christmas/3.html)

Step inside a butcher’s shop in the 1800s and what would you find?

Well, according to Thomas Miller (Picturesque sketches of London Past and Present 1852), first you would have to step over the gutter before the door, which literally ‘ran with blood’ (Victorian London). And be mindful of all those carcasses hanging on the outside of the shop! Displays of plucked fowl and the sawn-in-half bodies of pigs and cows pierced on hooks all over the outer shop walls. It was certainly not for the squeamish!

But of course, back in Victorian times, these displays would be a common sight. Unlike nowadays, High Streets of all sizes in the 1800s had butcher’s shops, and often more than one. Many would specialise, and a pork butchers was especially popular due to the fact that almost every part of the pig could be utilised.

Most shops had also been in the same family for decades, if not centuries, earning their reputations. Businesses would shout about where they sourced their meat, and were proud to sell local produce, the animals coming from nearby farms. Indeed, by the end of the century when meat imports were on the rise, butchers would display signs saying ‘No foreign meat’.

Despite many desperately poor people being unable to afford meat and living mainly on bread, scraps, and tea, statistics show that annual meat consumption per head had risen from 87 pounds in the 1830s to 132 pounds by the turn of the century (BBC). Butchers were busy people, and according to Thomas Miller, these ‘knights of the cleaver’ were doing well for themselves, with some even ‘keep[ing] his country-house’ (Victorian London). Even so, it was a gruesome job. In London at the start of the century, farms from all over the country drove their animals to Smithfield market every September and October where they were sold and slaughtered – Dickens describes the horrific scene in Oliver Twist, if you’re intrigued (Vic Sanborn). Butchers were slaughter men, and would kill the animals at their own premises then salt and store the meat in the cellar beneath the shop.

In a time of no refrigerators, salting and smoking meat was a good method of preservation. Yet, Victorians liked their meat a little aged, and sausages, for example, were hung in the windows for much longer than they are nowadays. Apparently, this made them taste better! By the end of the century, ice boxes began to be used.

Inside the shop, you would see a butcher with his ‘bare muscular arms’ (Thomas Miller). You might find yourself a little confused as this butcher conversed with his assistant, for butchers were famed for their backslang. This was a language made up of reversed words (‘boy’ would be ‘yob’, for example) which enabled butcher and assistant to talk without the customer understanding. Why? So they might charge different prices! It was known for butchers to price their meat according to what they thought they could get away with (BBC). Despite this rather salubrious trait, butchers tried to be clean. Fresh sawdust was put down each morning to soak up the spills of blood and cleared away at the end of the day. By the start of the twentieth century at least, butcher’s shop walls were tiled for better hygiene, and chopping boards and knives were scrubbed and washed at the end of each day. (1900s.org)

by Delphie Woods (https://www.delphinewoods.com/blog/posts/2019/july/a-victorian-butchers-shop/)

Ball’s Yard ??

————————————————————————————————————————

The Ball family of South Street

Thomas and Frances Ball had at least 12 children; Adolphus alias Dolf was number ten.

Adolphus ‘Dolf’ Ball (1830-1918)

“Adolphus was a machinist at Ball’s. I remember his two children, Fred and Lizzie; both died when about fourteen or thereabouts.”

Adolphus was born on February 2nd 1830 and married Priscilla Boam, daughter of engine worker Henry and Mary Anne (nee Daykin) of Shipley, in March 1854.

Adeline remembers their son Fred, who died in South Street in February 1867, aged nine, and daughter Lizzie (Eliza) who died, aged 14 during a scarlatina outbreak in the Spring of 1869.

There were younger children, Edwin, Harry, William, Annie Mary, Harriet and Clara Jane, after whose birth, in September 1871, the family moved to Radford where son Walter was added to the family in 1874.

Clara Jane died in Nottingham in August 1873, aged 2 years.

Priscilla Ball died in 1899 leaving a retired Adolphus living in Old Radford with his elder surviving daughter Annie Mary — now married to lace curtain maker John William Adcock — and neighbour to his other daughter Harriett, wife of lace draughtsman Linsey Stevens.

‘Dolf’ died in Nottingham in 1918, aged 88.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Thomas Ball (1827-1910)

Adeline recalls that ….. “The other son Tom lived in the next cottage. He carried on a small pork business. Tom was the only one of the Balls that I remember being an alien to the Lace Trade.”

Number nine and brother of Adolphus was Thomas Ball, born on November 20th 1827; he married Sarah Ann Tatham, eldest daughter of needlemaker Benjamin and Sarah (nee Hardy) in 1859.

Like most in his family Thomas was initially a lacemaker but at the beginning of 1862 started his pork butcher’s shop at Ball’s Yard, in premises recently occupied by William Gallemore and his family.

In November 1872 Thomas was putting up his Saturday stall in the Market Place when charwoman Ellen Hudson (nee Bostock) wandered by. Unfortunately she was too interested in what fruiterer Charles Chadwick was displaying on his nearby stall and accidentally kicked over Tommy’s bucket of water, slipped and fell.

As she was recovering her composure the butcher came over and gave her two kicks for good measure, each of which cost him a fine of half a crown and 8s costs at Heanor Petty Sessions.

In May 1879 Thomas began to detect a slight smell of gas at his premises, a smell which persisted throughout the week. On Friday evening he couldn’t raise a light and so he called in a young workman named Sisson – who was not ‘Gas Safe registered’!! — to check the system over.

You can guess what happened.

Young Sisson disconnected the meter, replaced it, tried the gas, whereupon there was a loud explosion and the meter was now in several pieces…. and not where they should be!!

All present narrowly escaped injury.

On one Saturday evening and Sunday morning in early September 1881 the town crier went around the streets of the town alerting folks to the disappearance of 13-year-old Fanny Mary Ball, eldest daughter of Thomas and Sarah Ann, — a slim girl described by the Ilkeston Pioneer as of “dark complexion, who walks very erect, being tall for her age”. (The Ilkeston Advertiser gave her a slight stoop!! — the rival newspapers could hardly ever agree!)

The girl almost always appeared in good spirits but was prone to fits of temper and on the previous Friday evening had been in a troublesome mood. Consequently her mother had boxed her ears while her father then sent her to bed, saying she had deserved her punishment.

The following morning she once more seemed in a good mood and said that she would like to visit her uncle Adolphus and family at Nottingham in the evening. Thomas however was still annoyed that she had upset her mother and would not let her go. Fanny Mary then went to work at Messrs Tatham’s factory in Belper Street as usual but later that same morning one of her factory workmates brought her wages to her home, saying that she had not been at work since about ten o’clock.

A short time later, around noon, platelayer Henry Booth of Mundy Street was near the West Hallam Ironworks when he saw Fanny Mary walking along the tow-path of the Nutbrook Canal and returned her wave. He was the last person to see her alive.

On Sunday evening her body was spotted in the water and recovered by the canal manager, Charles Pounder.

The inquest jury was unable to determine whether Fanny Mary had committed suicide or had accidentally fallen into the canal, and so returned an open verdict of ‘Found drowned’.

About 1888 Thomas and his family moved out of the Ball’s Yard area and into Bath Street, close to Station Court. That was when the South Street premises were put up for auction. They were described as having a frontage of 40 feet, with a cartway eight feet wide and leading to the rear. They were jointly owned with Charles Potts.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

As Adeline indicates, the men of this Ball family was predominantly but not exclusively lace makers.

Older brothers William, Frederick and Edwin were in the trade, while Alfred and George were engine fitters, and the youngest brother, Isaiah, was a joiner.

The other Ball children

Oldest child William Ball was born in 1809 and married Matilda Fox in December 1838. She was the daughter of framework knitter Joseph and Hannah (nee Paling …. one of the ‘Trowell’ Palings).

Matilda died of pneumonia on February 13th 1848 and William on May 13th 1859.

Oldest daughter Eliza Ball was born in January 1812 and married on October 3rd 1842 to West Hallam born Thomas Lee, a framework knitter at that time — the son of Michael and Sarah (nee Selby).

The childless couple lived all their married life in the East Street/Burr Lane area.

Born in 1814 Mary Ball married blacksmith William Burgin-Richardson on April 3rd 1838 … he was the illegitimate son of Mary Burgin-Richardson of West Hallam who five years after his birth married butcher John Hawley, later of South Street.

William died in 1855 (I believe) and Mary lived the remainder of her life with other members of her family, spending her last years in Basford with her son John, a joiner. and his family.

Mirah Ball was born in 1816 and married on September 19th 1836 to sinker maker John Silvester. He died, aged 36, on May 15th 1847, a couple of months before the birth of their fifth child Fanny Elizabeth. (A sinker maker made lead weights used in a hosiery knitting machine).

In 1852 widow Mirah married stockinger and widower Henry Holland but just over four years later she was once more a widow, and with two more children.

Then she kept a shop in South Street but later served as a domestic nurse … on her death, September 6th 1882, she was described as ‘nurse for William Tatham, needlemaker’ of Stanley House in Stanton Road. (DM)

Frederick Ball was born in 1819 and after his marriage to Eliza Kirk on September 1st 1850 lived the rest of his life in the Burr Lane area. Both died in that street, on November 30th 1895 and March 14th 1899 respectively.

Edwin Ball was born on March 15th, 1821 and before his death in Burr Lane on February 1st, 1895 he married three times.

His first wife was Sarah Crich, daughter of collier Jonas and Sarah (nee Buss) whom he married in 1844 and who died on March 25th 1857, aged 30.

Less than five months later, on August 11th 1857, he married Eastwood-born Hannah Askew, daughter of framesmith George and Susanna (nee Limb), and lived together in the Chapel Street area. … Hannah died at their home of 11 Burr Lane on June 4th 1890.

And in 1892 Edwin married Caroline Robey (nee Frazer) widow of fruiterer John Bower Robey of Robey’s Yard, South Street.

Three marriages and two unnamed children who died in infancy.

His later working life was spent as foreman at the Ball’s Factory in Albion Place/Burr Lane though he ‘retired’ some years before his death, Then he lived in a semi-detached villa, built especially for him, at 10 Burr Lane. (This would be on the west side of the lane, a couple of houses south of Uplands house). He was a Liberal in politics and a member of the Independent Chapel in Pimlico .. the two often went together.

Edwin died on February 1st 1895, aged 73. On this Friday afternoon he had just paid his usual visit to the Liberal Club in the Lower Market Place, got home to spend the everning with his wife and children, playing dominoes until supper time. However not feeling too well he decided to retire to bed. His wife, Caroline, heard a stumble from upstairs. She investigated and was so alarmed at his condition that she sent out for assistance. But Edwin rapidly ‘sunk’ and died shortly after 10 o’clock.

Edwin was buried in Eastwood Churchyard, his previous wife being a native of Eastwood and was buried there.

Born in 1823 Alfred Ball married Sarah Bircumshaw on November 11th 1844. She was the daughter of framework knitter George and Ann (nee Straw) and had been orphaned at the age of seven when both her parents died in August 1831.

The family eventually settled in the Newton-le-Willows area of Lancashire where Alfred died on March 31st 1895.

George Ball was born in 1825 and his first wife, whom he married on April 9th 1849, was Ellen Straw, eldest child of Heanor Road coal miner Wheatley and Sarah (nee Hutchinson).

Ellen died of typhus on September 6th 1859 and on October 22nd of the following year George married Hannah Woodroffe, born in Stanford on Soar, daughter of agricultural labourer Daniel and Hannah (nee Blood).

In the early 1860’s the family moved to Derby where George and Hannah were still living at the end of the century.

Ebenezer Ball was born in 1832 and died in 1835.

Isaiah Ball, born in 1835, married on January 25th 1857 to Elizabeth Tatham, eldest child of lace maker Zachariah and Sarah (nee Hunt).

About 1860 they moved to Kensington, London, where Isaiah died in 1886. Eizabeth was still there at the end of the century.

Between Ball’s shop and the three shops below the present South Street Schools, was an orchard, the hedge standing out from the present building line, and a single flag pavement in front.