Now walking on from James Chadwick and family ….. Adeline leads us to “three or four cottages which were built below Butcher Twell’s shop and field, also Brussels Terrace facing the old branch line”.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

Brussels Terrace and its Victorian inhabitants

George Spowage or Spouge conducted his carrier business from the stables of the Rutland Arms Hotel and 12 Mundy Street. He was declared bankrupt in February 1879 at which time his erstwhile weekly advert disappeared for ever from the front page of the Ilkeston Pioneer. In March his assets were liquidated to pay creditors.

Richard Birch Daykin then replaced George’s trade at the Rutland Hotel stables.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

In May 1873 James Burton was lodging in the Terrace and was relaxing on the sofa when into the house wandered Mary Ann Riley. After speaking to James briefly she left the house, when the lodger noticed that his pocket knife, which he had recently been using, had disappeared. He charged Mary Ann with stealing it but at Ilkeston Petty Sessions she was discharged, primarily because the lost knife had not been recovered.

Less than a week later Mary Ann appeared at Heanor Petty Sessions, charged with ‘wandering abroad, and of having no means of existence at Ilkeston’.

For about a fortnight she and her son, aged about two, had been living ‘rough’, sleeping in outhouses and cabins wherever they could. On several occasions she had been asked to leave the town and now she was to be imprisoned for two weeks.

Prior to her imprisonment Mary Ann had given the boy away to a local watchmaker, “occupying a respectable position in Ilkeston, who had adopted it as his own, so that it was now much changed for the better”.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

This short article appeared in the Ilkeston Pioneer, April 20th, 1882 …

Curious incident — On Wednesday afternoon a large number of people assembled at the Market-hall, Ilkeston to witness a curious spectacle, viz. the sale of a coffin which had been seized for debt, and a singular tale hangs over the coffin which may be summed up in a few words.

Some ten years ago a man living in Brussels-terrace, Ilkeston, was taunted by his friends with the prospect of a pauper’s burial owing to his drunken habits. Determined that his remains should be encased in no pauper’s shell, he procured a good sound coffin and had a plate put upon it with his name and the date of his birth and on which space was left for the date of his decease whenever it should occur. This ghastly article he has cherished for many years, but at last it has fallen prey to the hands of his creditors who, as the money was not forthcoming to redeem it, caused it to be put up for competition.

William Drury Lowe was this old resident of Brussels Terrace who had the foresight to prepare a coffin for his future burial. He was born about 1808, son of Nottingham Road joiner and brewer Christopher and Mary (nee Allen). He was therefore the brother of ….

Mary Lowe, later the wife of Joseph Moss and mother of South Street pawnbroker John Moss.

John Lowe, at one time gentleman farmer of Larklands House.

Ann Lowe, wife of Bath Street lacemaker James McKenna.

Elizabeth Lowe, wife of Bath Street house agent and rent collector William Smith.

Ruth Lowe, wife of Woolstan Marshall White, Samuel Revill and Charles Haslam (for six months).

At one time William Drury Lowe owned substantial property at Gallows Inn and had been a successful wheelwright with a respected reputation as an excellent craftsman. However he seems to have been a black sheep of the family …… his ‘intemperate habits’ had led him into hard times, his property being gradually lost.

Local gossip suggested that some members of his family taunted William that he would never have enough resources to afford his own coffin when he died. The wheelwright was determined to prove them wrong and so before he ‘departed this mortal coil‘ he built his own bespoke coffin, complete with breastplate bearing his name, date of birth and a blank space … to be filled in later!! This coffin was kept in its own wooden box and proudly stood in one corner of his front room.

Further financial difficulties and bad debts for William in the early 1880’s led the bailiffs to his Brussels Terrace door when they carted off his funerary box.

Though not before William had shown his displeasure by ‘pasting’ one of the bailiffs. And this led to even more financial difficulties, as he then found himself at the Petty Sessions with a subsequent fine of £1 with costs.

All of these costs meant that William’s coffin now had to be sold off — hence the auction, in April, at Ilkeston’s Market hall, described by the Pioneer.

Less than two weeks later, on a Thursday early afternoon in May 1882, William took a steady walk down Derby Road towards Straw’s Bridge.

Less than two hours later his lifeless body was discovered in the Nutbrook Canal by miner George Moon of Pewitt Wharf. His jacket and hat lay undisturbed on the tow path there. In his pockets was found a short note … “I am nothing but a murdered old man!” … and one halfpenny.

Unable to record a verdict of suicide, the inquest jury returned an open verdict of ‘Found drowned’.

P.S. William never did pay his Petty Sessions fine.

P.P.S. His prepared coffin was reclaimed and he thus slept ‘at last encased in his own handiwork’. He was buried at St. Mary’s Church on May 13th 1882.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

P.C. William Colton was on duty just before 4am. one Sunday morning in May 1875, patrolling near the Town Station, when he spotted old James Tomasin, horse breaker of nearby Brussels Terrace, approaching some coal wagons in the Butterley Company’s sidings there. Following at a distance, he spotted James break up a few lumps of coal and put them into his basket. When challenged by the law the old man replied that he had no coal at all in his house. For this reason the magistrates at the Petty Sessions felt sorry for James, sentenced him to seven days in prison but without hard labour, though if he had not had a good character and been an old man he would have spent longer in jail. Born in Shardlow John was then 66 years old, had lived in Ilkeston for 40 years, and had initially worked as a groom, but as his family increased along with the financial burden upon him, he had sought more lucrative employment as a labourer. He was thrice married and claimed to be the father of 20 children – ten of each sex – whom he had brought up without any parish assistance. Five of his sons had gone into the army – two had died and three were still serving.

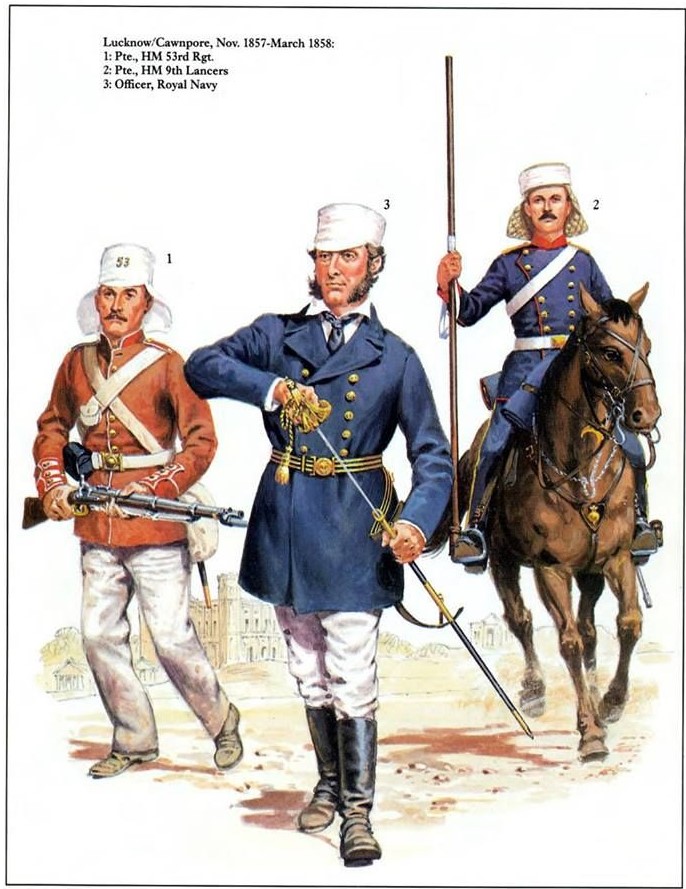

One of the sons was Thomas Banton Tomasin, born in 1831, the son of James and his first wife, Elizabeth Banton. Thomas found himself serving in the 53rd Regiment at India during the uprising there in the later 1850’s. (See first figure, below) In April 1858 he wrote a lengthy, informative letter, full of heroism and battle detail, to his dad: —

Camp before Lucknow, April 17th, 1858.

My dear father, Our Regiment left Calcutta on the 17th of October, and since that time until the fall of Lucknow we had little or no repose.

We commenced by giving chase to a party of the Ramgurh Battalion that had encamped near Chittrae, and they kept us at it night and day for upwards of three months, however they were too wide awake to be caught napping. For ninety-seven hours we were without a halt or breaking our fast –sometimes climbing the hills, then through jungles and crossing swamps, again traversing a sandy plain, until our men were actually falling down worn with fatigue and the burning heat of the sun.

At last we came in sight of the enemy but were not a little surprised when we saw they were something like four thousand strong and a strong body of artillery, and our whole force amounted to sixty men — no ordnance. We got the order to fix bayonets which was soon obeyed, and with a wild hurrah we dashed at them, met by vollies of musketry and cannons playing on us from three different directions; their grape and canister did fearful execution amongst us, but as soon as our bayonets were fairly at play we quickly silenced them, in fact we turned their own big guns on them as they flew pell-mell, and left us masters of the field after two hours hard fighting; they left seven hundred dead on the field.

We took possession of their camp entire, with about two thousand camels, eight elephants, seven boxes of treasure and plunder of every description. Our next piece of business was at the bloody field of Cugewa; here our Colonel was shot through the head in front of his Regiment. This was a short but desperate affair, but the British bayonet was too cold for them and they beat a retreat with great loss; we then reached Lucknow without interruption, and commenced operations for the relief of General Havelock and gained our object in twelve days; then back to Cawnpore, and in a short time we retook that city and chased the rebels for forty-nine hours, and overtook a party endeavouring to cross the river Ganges with some cannon, from whom we took twenty-one pieces without losing a man, and then reached Bithcor, the seat of the once-powerful Nena Sahib.

Our next route was to Furekabad and Futtepore, taking each city as we went along; then to Chaw, where fourteen of our men were blown up by the bursting of a mine; and finally accomplished the destruction of Lucknow, after nineteen days’ hard fighting, which became ours on the 21st of March; but the war is not over yet. So long as a Sepoy remains at large he will do his best to give us some trouble. I have had a many narrow escapes, but as yet, thank God, I retain a whole skin.

The Second Relief of Lucknow, by Thomas Jones Barker

The Second Relief of Lucknow, by Thomas Jones Barker

I was not a little surprised when you mentioned Captain Ash’s name; I was not aware he would have recollected an insignificant object like me so long — I am glad to hear that such is not the case. I well remember his son, Mr. Andrew, also his elder brother, but I forget his name; he used to teach my class at the Church Sunday School with his father — that was the happiest time of my life — I often think of those dear old times; it seems as but a few days since.

I must now conclude with my best and kindest love to you all, as I hope to remain your ever affectionate son and well-wisher. T.B. Tomasin, No. 6 Company, H.M.’s 53rd Regiment. — P.S. Please give my humble respects to Captain Ash.

*’Captain Ash’ was land proprietor Henry Ash (1799-1869) who lived at Beers or Bears Lane, Cotmanhay (later renamed Ash Street). He died at Hope Cottage, Cotmanhay. His son, Andrew, was born in Ireland, about 1831. His elder brother was James Ash, also born in Ireland, about 1826.

Thomas Banton Tomasin died on May 15th 1860, during his return passage back to England.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

At this time, further up Bath Street, on the same side as Brussels Terrace, just past Chapel Street and neighbouring Smith’s Yard, lived hosier John Stocks and his family. His son, Isaac, enlisted with the 90th Light Infantry which also served in India, and Isaac also wrote home to his father, as exampled here ….

April 1858 … Lucknow was taken with ease; we soon got the natives on the run, and kept them to it. We have lost very few men, only 150 since we left home; and I have escaped all dangers so far. We are very comfortable in the city.

I did not receive your letter containing stamps; I suppose it would be in the mail that was robbed by the sweet little Sepoys, who were thought so much of before the mutiny that the gentry had their likenesses painted on the walls. A European soldier was thought nothing of in this country. When on parade, the Sepoys are pretty spectacles, with their charming belts, oiled faces, and bootless shanks. Had our hearts been tender when we were relieving the women and children at Lucknow, they would all have been broken; all the thanks that we got for it was that we were dirty soldiers, and anything but gentlemen, except when they saw us charge, and found their births safe; then they said “Oh, brave Britons !”

———————————————————————————————————————————————

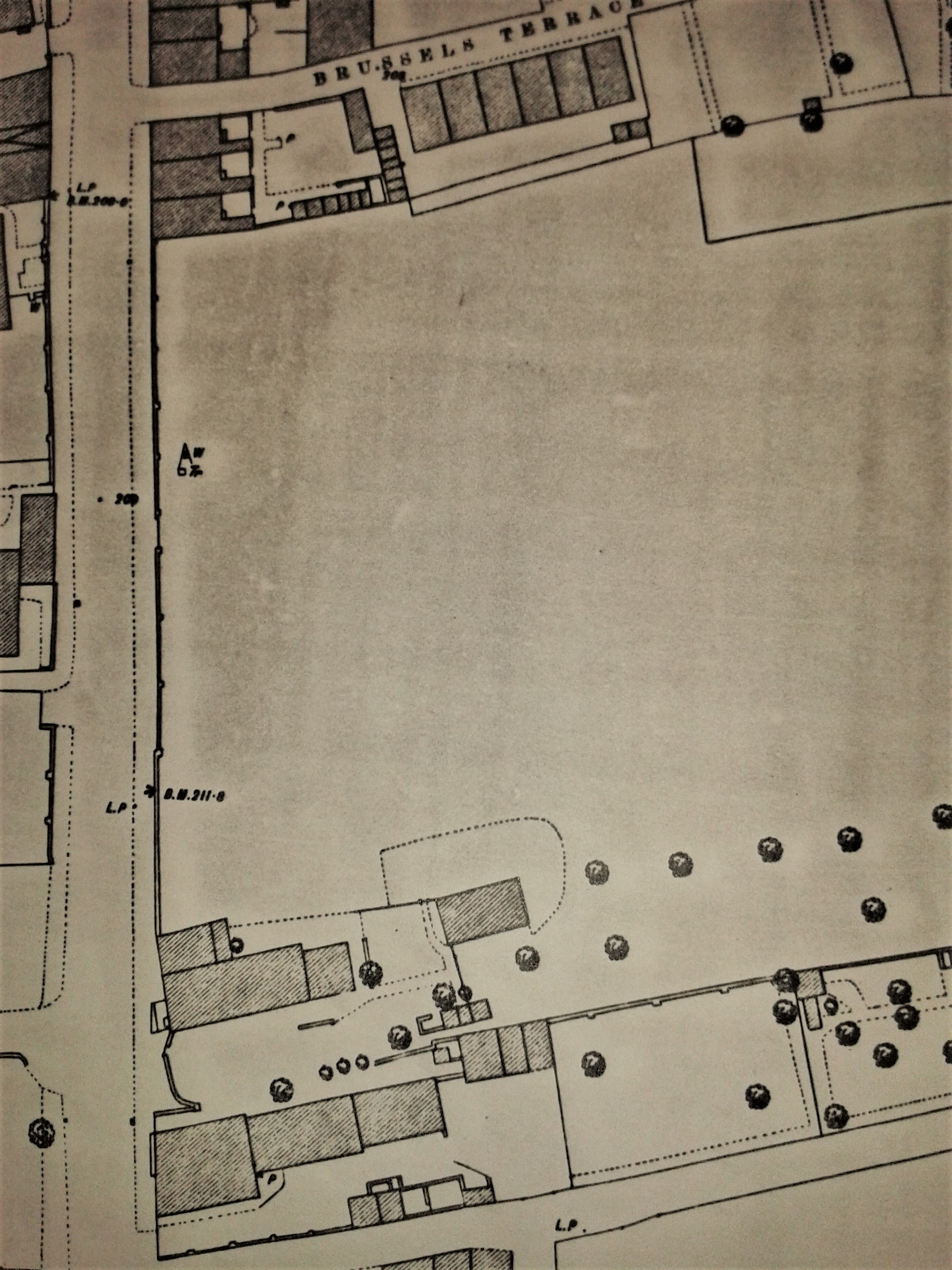

Below you can see Brussels Terrace, together with the cottages, either side of it, mentioned by Adeline (above), and as we walk on, up Bath Street (on the left) there is not a lot to see, except Twells’ Field

———————————————————————————————————————————————

The Victorian era draws to a close

As the end of the nineteenth century came into sight, life for some residents of Brussels Terrace was little improved since Victoria had come to the throne.

Born in Critchley Street, Ilkeston in 1871, Joseph Atkin was the son of brickmaker George and Ruth (nee Bramley). By 1898 he was living in Brussels Terrace and working as a coalminer at Manners Colliery; by this time he had lost a wife and gained four children. Joseph had married Agnes Cope in 1891, shortly after she had given birth to her illegitimate daughter Ruth (on March 13th 1891). The couple then had three further daughters — Hannah, Emily and Agnes junior — before the mother died in 1896, aged 25 and just two weeks after the birth of her last child.

Perhaps struggling to cope with these young children Joseph employed the help of his mother-in-law Emma Cope (nee Stokes) who agreed to supervise care for the children and to take in and look after baby Agnes — which she did until the child was about two years old. During this period (according to Emma !!) they were kept clean and well fed. Then, in late 1897 “housekeeper” Ellen Woolridge, who apparently ‘knew nothing about children and was no good to motherless children’, came into the household and circumstances seemed to change.

Ten months later Joseph Atkin found himself living at 29 Brussels Terrace with housekeeper Ellen and four children, not one of them over seven years old — three of them certainly his children while the other was quite possibly his also. It was at this point, on September 15th, 1898, that he was called to appear at Ilkeston Petty Sessions, along with Ellen, charged with ‘willfully neglecting the four children to the detriment of their health’. When Inspector Cooper of the N.S.P.C.C. had visited their house he found it filthy and poorly furnished, while the children were ill-nourished, poorly clad and dirty. The three elder girls’ heads were thick with vermin and they were sleeping together on a dirty mattress, with just a bit of stair carpet for covering. Only the baby escaped the worst of the conditions, still being protected by her grandmother’s caring shield. Ellen’s defence was that she received only 10s from Joseph to feed and clothe the youngsters, had no soap to keep them clean and had had to resort to pawning their clothes to get food. The court was not sympathetic however, and both defendants were sentenced to two months in prison with hard labour. Meanwhile the three eldest children were sent to the workhouse while, once more, grandmother Emma took care of infant Agnes.

After his release from jail Joseph was facing the same ‘child-care’ problems, and decided upon a similar solution — another ‘housekeeper’ !! This was Ellen Moore (nee Barnes) who had married collier Herbert Cornelius Moore on October 22nd, 1893. In the year after this wedding Ellen gave birth to a son, James Jervis Moore, but this was not before she had been deserted by her husband. The marriage had lasted only two weeks and so it is probable that James Jervis was also illegitimate.

On the 1901 Ilkeston census Joseph Atkin and Ellen Moore are living together, both described as widowed, with three of Joseph’s daughters and Hannah’s (illegitimate ?) son. Unfortunately these details were not correct, and the subsequent deception and conduct were to lead to another court appearance on July 13th, 1905. This time Ellen Moore appeared at Derby Summer Assizes charged with marrying Joseph Atkin on February 22nd, 1902 at Babbington Chapel near Awsworth, while her former husband was still alive.

Ellen vigorously pleaded her innocence and set out her case. She had married Herbert Cornelius Moore in 1893, who had then deserted her two weeks later to live with another woman at Eckington. He briefly returned to live with her before once more deserting her altogether. She subsequently heard that he had married a second time before his father told her that he had died. Thus, for the three years before Ellen married Joseph she had believed that she was a widow — and so (in her eyes) her entry on the census was accurate. She had tried to authenticate her husband’s death but it was not easy to find out, as Herbert Cornelius “was all over the globe” ! It seems that Ellen’s testimony was convincing. A verdict of ‘Not Guilty’ was returned and she was discharged.

Her (original) husband was not so lucky however. The day after Ellen’s trial, Herbert Cornelius Moore appeared at the same court, charged with marrying Hannah Maria Dunmore on August 10th, 1896, at Mansfield, his former wife being alive. And also on August 22nd, 1903, of marrying Sarah Maria Long at Heanor. A double bigamist ?? Of course Herbert told a different story to that of Ellen. He was the one who had been deserted by his first wife who had gone to live with another man, just two weeks after the marriage. He took her back, forgave her, but very soon after she was off again! Herbert then believed that he was free to marry again and did so — twice !! He then pleaded guilty to the first charge of bigamy but not to the second one. The prosecution was prepared to accept this and so, on July 14th,1905, he was sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

The quiet and worthy Twells family.

Just beyond Brussels Terrace we discover “Twells’ field, which ran parallel to Bath Street. Here lived Mr. and Mrs. Twells, and their little boy Willie. Mr. Twells died in early manhood”. We are now almost opposite the Poplar Inn. Twells’ field lay between Brussels Terrace and Northgate Street, north to south, and stretching from Bath Street to the Durham Ox Inn, west to east.

Colliery manager John Twells and his wife Catherine (nee Buckland) were prominent Baptists, “very quiet, worthy people, and had the respect of all who knew them”. (Bath Street). They were married on May 8th 1811

John died on November 20th 1833, aged 47, and his son William – born on October 8th 1821 — continued to live with his mother at the Bath Street home. It is he who is Adeline’s ‘Mr Twells’ who ‘died in early manhood’.

Their son William was apprenticed with John Mellor, butcher of South Street. For his first wife he married Ann West in 1849. She was born into the Baptist family of Market Place drapers William Barnes West and Hannah (nee Twells) in January 1824. Shortly after the birth of their only child, Hannah, in July 1850, Ann died of child bed or puerperal fever, aged 26.

On New Year’s Day of 1861 William married his second wife, Mary Malin of Ashleyhay, oldest daughter of George and Elizabeth (nee Annable) at the Baptist Chapel in Wirksworth. Their son William was born in the same year. William senior died in the following year — on June 3rd 1862 — aged 40, of tubercular pneumonia.

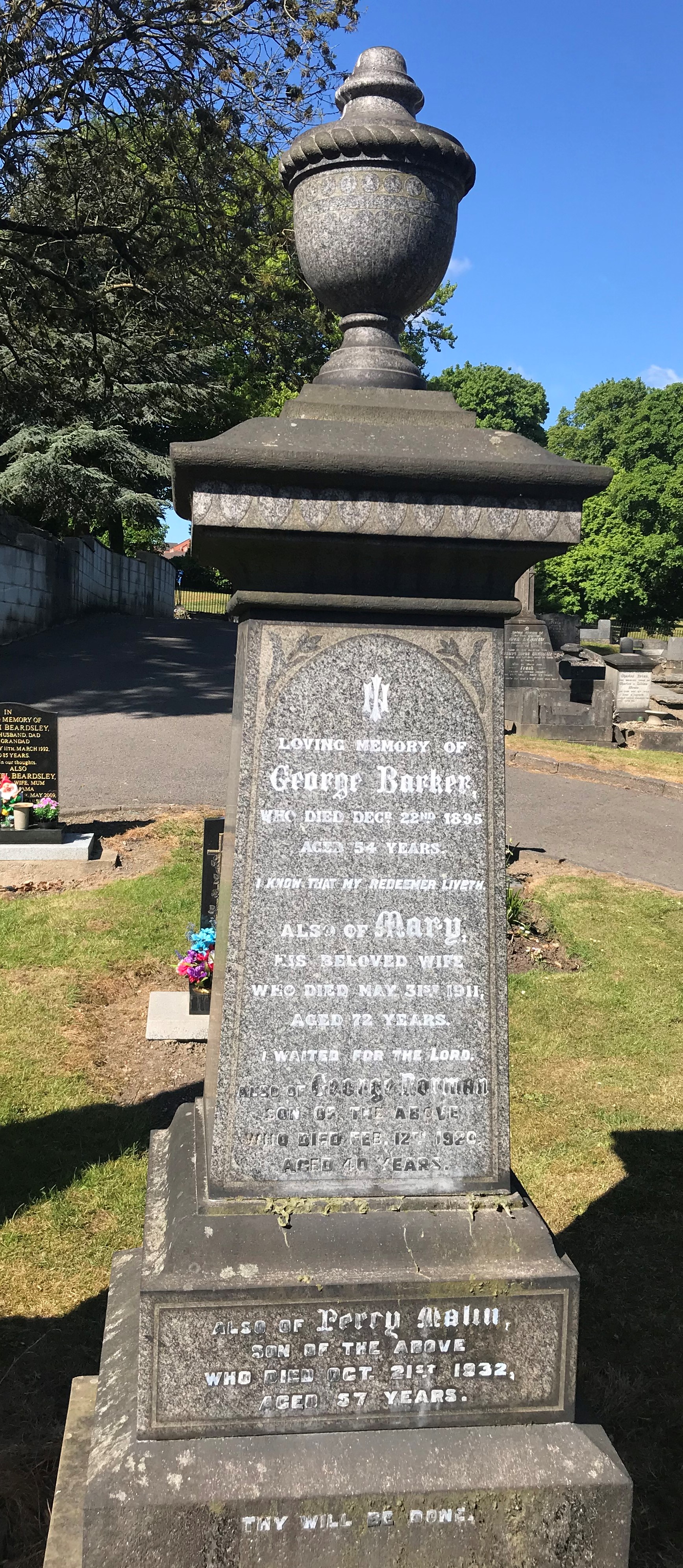

Adeline tells us that “years later Mrs. Twells married her second husband, Mr. George Barker, registrar of births and deaths”. This “Mrs. Twells” was William’s second wife Mary, now his widow. She then went on to marry George Barker, son of lace manufacturer Thomas and Mary (nee Mills) — on March 10th 1868.

George was a small ware and shoe dealer in Bath Street who in 1872 became Registrar of Births and Deaths after the retirement of Ilkeston doctor George Blake Norman. His annual salary was £60. He and his ancestors were all long-term members of the Independent Church; “his family connections date back to the foundation days (of the Church)”. His wife Mary was received ‘by letter of transfer’ from the Baptist Church, Ilkeston into the Independent Church.

George was a teacher and then Superintendent of his chapel’s Sunday school and for many years served as a Deacon. With his family he left Bath Street to live in Malin House, St Mary Street. Here he also had his office as Registrar.

A view of Malin House 2015 … the house name can be seen between the two windows on the right.

George died at Malin House on December 22nd, 1895, aged 54, and was buried in Park Cemetery.

This death left the position of Registrar of Births and Deaths vacant. It was filled by George’s eldest child, Annie Mary. She had often served as her father’s deputy before his death.

George’s wife Mary died at Malin House on May 31st, 1911.

A stained glass window to their memory was placed in the Wharncliffe Road Congregational Church by their family.

“The urn represents a funeral urn and is thought to symbolize immortality.

It is commonly believed to testify to the death of the body and the dust into which the dead body will change, while the spirit of the departed eternally rests with God.”

(Kimberly Powell at ThoughtCo.com)

A false Birth Registration: 1896

If you examine the birth registrations at Ilkeston you will find, in 1896, the name of Henry Spiby … a name cloaked in deception.

On December 17th 1896 registrar Annie Mary Barker was in her office in St. Mary Street when she was visited by Elizabeth Spiby. She was the wife of Charles Spiby, a coal contractor, and the daughter of John Beardsley of Heanor Road. She had married Charles in 1875 and now was living in North Road with her husband and several children. Previous to Henry, her last child had been born in 1891.

Elizabeth arrived at Annie Mary’s office to register the birth of her son, naming husband Charles as the father; thus the child’s name was entered as “Henry Spiby”.

Within a couple of weeks however one of Elizabeth’s daughters appeared in court to affiliate the child — and then it emerged that Henry was not Elizabeth’s son. She subsequently paid a second visit to Annie Mary’s office to try and set the record straight; she said that she was going to adopt the child and so she thought that it didn’t matter … but it was too late. Elizabeth had already been charged under the 1874 Births and Deaths Registration Act for an unlawful registration and she was in serious trouble — the maximum punishment was seven years in prison. Sitting in judgement at the Petty Sessions, Ilkeston Mayor Samuel Richards took pity on penitent Elizabeth and fined her £1 with 10s 6d costs.

It would appear, from subsequent censuses, that Charles and Elizabeth did ‘adopt’ Henry as their son.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Apart from son Willie, John and Catherine Twells had at least four other children.

Eliza died in 1829, aged 17; Ann the First died in 1821, aged 6; Ann the Second died in 1847, aged 19; and John died in 1830, aged 8 months.

All were buried at the Baptist Chapel in South Street.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

We next encounter William Riley, unfortunate butcher