Dalby House

Leaving behind Penty Lee’s garden we pause as we look towards Dalby House and to the Vicarage beyond that.

Deriving its name from owner John Dalby in 1806, Dalby House elicited a not altogether complimentary description from local historian, Venerable Whitehead, writing in the Pioneer of 1854.

He complained that Dalby House had an “economy of space on its ground floor” more suitable to a house on the crowded streets of London than the abode of a country gentleman.

However its site was fit for a castle and afforded magnificent views over the meandering Erewash river, over the villages of Cossall and Strelley, and over the hills of Bramcote.

In the same article the Park is described as a “picturesque residence – but its modern Gothic is not the perfection of domestic architecture”. Venerable Whitehead continued: “We love its ivy covered walls and its bowery trees – its English comfort and English hospitality; and the noble specimen of an Englishman presented in the person of its honoured occupant – the chief of his clan”.

That chief would be coal master Samuel Potter, the occupant of the Park.

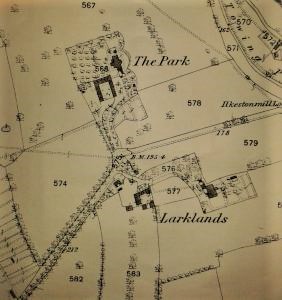

Apart from a labourer’s cottage the only residence other than the Park in that immediate neighbourhood was the Larklands house.

In 1881 this was described as “of peculiar formation, consisting of a number of rooms opening into a long passage. The doors of these rooms being locked on the outside, it is not possible to proceed from one to the other, so that the only mode of entrance (is) by the (sash) windows”. (NG)

The Park and Larklands c1880

In 1897 Larklands was occupied by Nottingham lace manufacturer Samuel Howard and his family, and in April of that year it was put up for auction. It was described as adjoining theErewash Canal and having an extensive frontage to Park Road. On the Larklands estate, which totalled 14 acres, it had been proposed to construct several new streets called Fletcher Gate, Howard Avenue, Andrews Avenue and Chambers Avenue. The Larklands house itself contained three reception rooms, six bedrooms, a large garden, excellent stabling and outbuildings. The auction however was unsuccessful and Larklands remained unsold.

From the lofty Market Place the Ilkeston News (1855) waxed lyrical about the view over the “broad and ample scenery of the valley of the Erewash and the dale of Stanton.

“Rich woods greet the eye, — here and there covering the summits, in the summer season displaying bright green splendours, tinged with the delicate hues of the rainbow. We do not know a more cheering ride than a few miles to, and a little way beyond, the romantic village of Trowell, whose time-worn tower awakens endearing associations of long past days. The country near the old bridge at ‘Gallows Inn’, (ominous name) is truly of a superior character, — the river winds its silent way through rich meadow land, and as the hill rises on the Nottinghamshire side it is right well greeted by the far stretching ascent opposite, on which the Ilkeston church appears with conspicuous front, commanding the scenery around for many miles”.

And twenty years later, from another lofty perch (the top of St. Mary’s Church tower) and with the aid of a telescope, another observer described his view to the south-west.

… to a lovely Derby dale about 4 miles distant … I see the relic of an old Monastery which was in its prime over three centuries ago, in the early days of HenryVIII.

It did not however escape the blind indescriminate persecution of that King’s Minister, Thomas Cromwell, who razed the building to the ground, leaving only one stone arch, which marks the east end of that once splendid Dale Abbey.

For over 300 years this arch has stood in dreary solitude.

It is impossible to give to children of neighbouring schools a greater treat than a few hours at Dale.

The old Abbey is not the only point of interest — there is also the church and the romantic wood — romantic because of the Hermit’s cave, which has existed there in its present state for hundreds of years.

The mad fanaticism of the man who hewed out this humble dwelling resulted at last in the magnificent Abbey mentioned.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Old Park or Old Hollows

At Dalby House we can contemplate a letter to the Pioneer of June 1866, signed by ‘Ilkestonian’ and bemoaning the lack of a ‘People’s Park’ in the town, “where the men, women, and children … can walk and play”. The Cricket Ground was not a pleasant nor safe place, and was only available by courtesy of the cricketers. Ilkestonian’s own solution lay in the field called the ‘Old Park’, part of Church property, east of the Vicarage, which on Sunday afternoons is ‘literally thronged’.

‘Ilkestonian’ described it thus:

“Its sunny banks and enticing slopes seeming to possess a real charm for the various young people who desire to luxuriously bask themselves in the warm sunshine, or run down the mimic hills; and last Sunday afternoon the sight of 70 or 100 congregated there made me wish we could…procure this pleasant place for a perpetual and rightful Park for our townspeople. The land is so overrun by children, and so intersected by footpaths, that it cannot be very profitable to the occupier; moreover it possesses such pleasing variety of surface that half the usual labour necessary for forming a recreation ground would be done away with. It would require only the walks forming, shrubs planting, and a lodge building”.

Taking an early evening walk in this same field, just prior to Christmas of the following year, a correspondent in the same newspaper encountered two drunken would-be pugilists. They were obviously intent upon doing serious harm to each other and the correspondent listened intently to their ‘unintelligent stultilogence’.

“Thae wants to feight mae, dustner?

Ah!

Well, pool off thee coot and feight.

Nay, ah shonner; ahl feight thae weight on.

Nay, poolt off.

Well, hit mae.

Ah wool.

Well, dowt; thae dahner

Ah dah.

The fight then began in earnest as the two engaged in a horizontal wrestling match at ground level, the taller and stronger of the pair eventually wrapping his hands around the windpipe of the other. At this point the observer cried out.

“My good man, come away from that worthless fellow, and don’t take the trouble to hurt him”.

His interjection was sufficient.

The fighters retreated and he was left to contemplate the nature of the town’s social problems:

“What a shame and pity it is that education and temperance do not more effectually and extensively prevail over the manners and habits of the lower classes of Ilkeston!”

Fifteen years later and ‘Rambler’, writing in the Pioneer, was still pleading for this area – familiarly known as the Old Hollows – to be developed as a place of recreation.

“As it commands an extensive and pleasing view of a large extent of picturesque landscape, I know of no place which offers more attractions, or would be more convenient” even though several trees had recently been lost from its hedgerows. (IP May 1882)

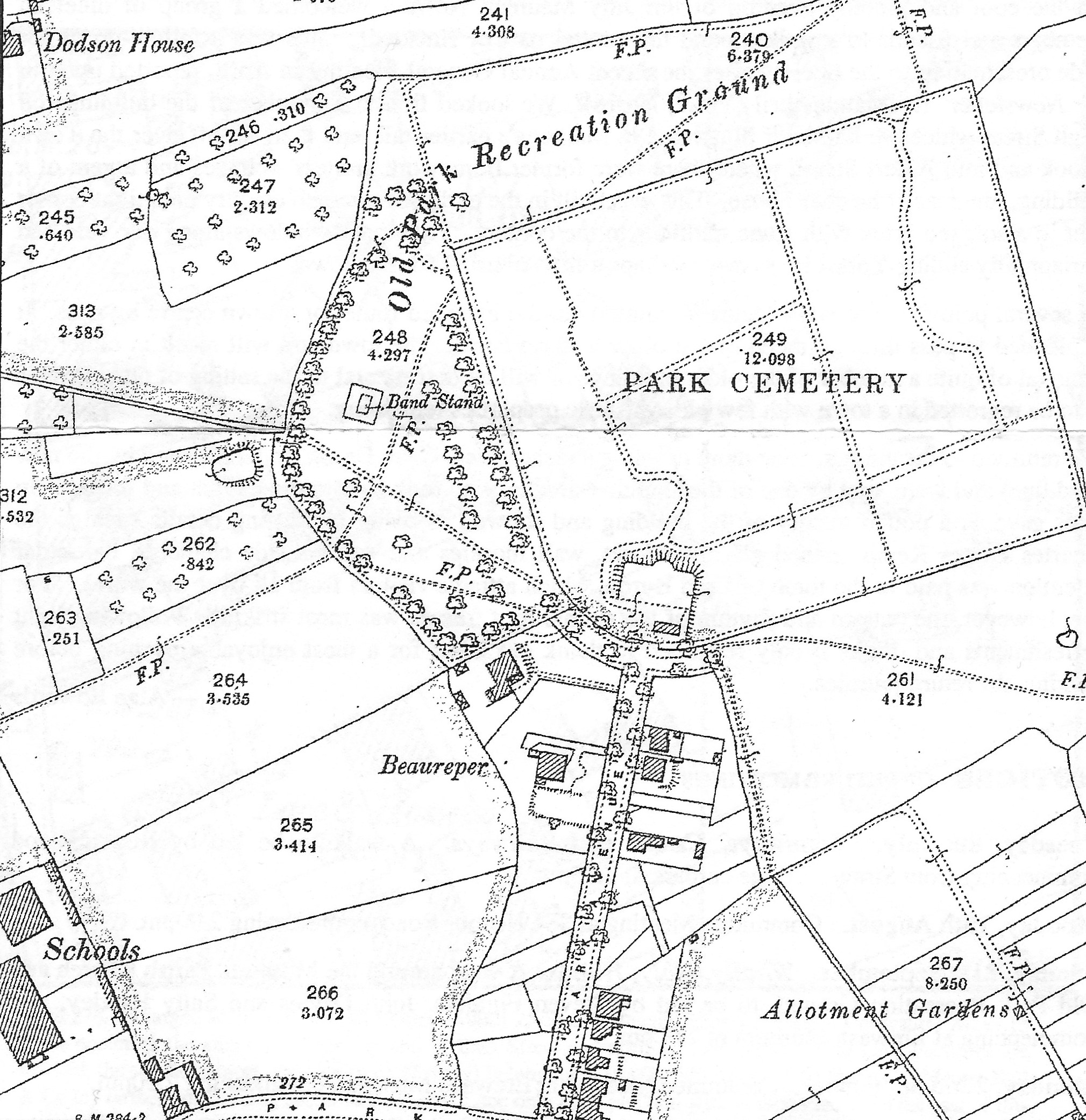

A new park and a new water fountain (almost) … and Park Avenue

And here, below, is what Ilkestonian was wishing for, almost 50 years earlier …. the area at the culmination of Victorian Ilkeston, showing a ‘People’s Park‘, with several clues to the date of the map. You might be able to spot the routes of later roads in the area, while many of the paths shown still exist.

A park complete with band stand, and a recreation area, to rival the Victoria Park and Rutland ‘Rec’ on the other side of the town. It was the venue for many open-air concerts in the late 1890s.

Beaureper was the home of solicitor Charles John Jackson, while the slightly larger house to its NNW was Parkhyrst, home of the family of chemist and druggist William Merry.

And you can see Park Avenue, much less developed than today, one of the town’s more exclusive residential areas, its path from bottom middle up towards the relatively new Park Cemetery.

As the Victorian era was drawing to a close, the Avenue also housed the following …

At number 1, lace manufacturer Charles Alan Sudbury and family. He was a son of Ilkeston’s first mayor, Francis Sudbury

3. architect and Borough surveyor, Henry James Kilford and family

5 (Fenwick), spinster sisters Sarah and Adela Green

7. needlemaker Samuel Bloor and family

9. Sarah Blench (nee Fletcher), widow of farmer William, and her family

19. mechanical engineer David Thompson and his family

23. lace trade pattern maker Joseph Barber and his wife

(?) lace draughtsman Frank Walker Harvey and family

31. carpenter and joiner Francis Herbert Goddard with his spinster sisters Lavinia and Mary Elizabeth

33. lace warehouseman James Butt and his family

You might be able to identify most of these on the map directly above … number 1 is at the bottom of Park Avenue, where it joins Park Road. As the Avenue had not been fully developed at this time the numbers were applied later.

In 1898 a subscription fountation had been ordered for this Old Park recreation area but its placement had to be ‘put on hold’. At the beginning of October an advertised public unveiling ceremony, attended by the Mayor, was cancelled when the fountain did not arrive on time. When it did arrive but before it was installed on the ‘Hilly Holies’, Public Surveyor Kilford inspected it and unhesitatingly condemned it as unfit for its intended use. Even Councillor Joseph Scattergood — who had promoted the cause of the fountain — had to admit that the condemnation was a justifiable one. It appeared that, in order to meet the deadline of installation, the fountain’s manufacture had to be rushed and proper prior and strict inspection had been foregone.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Dr. Norman and family

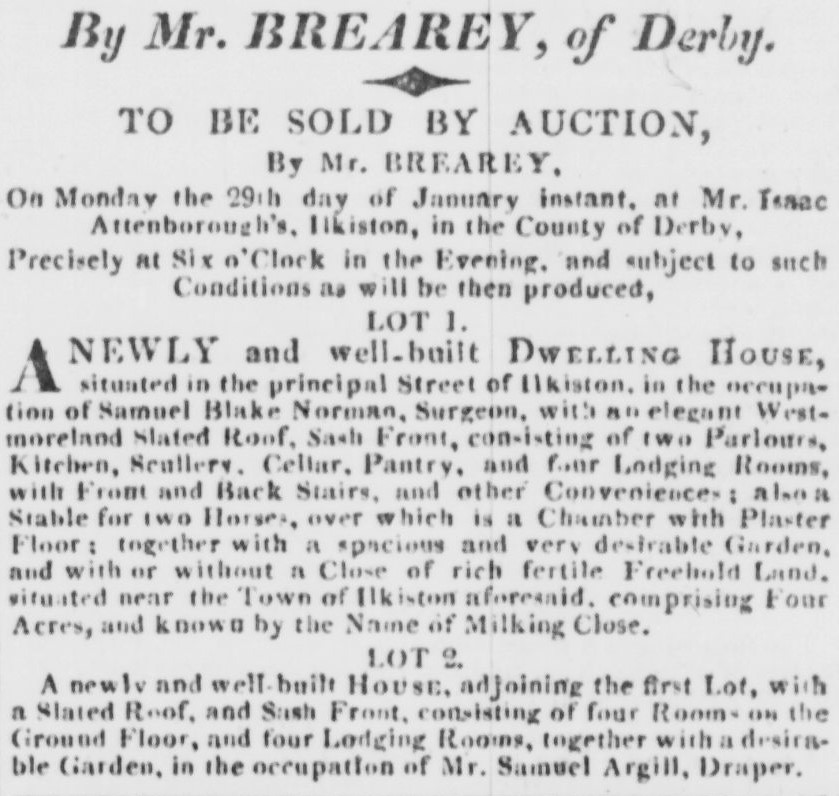

George Blake Norman was born on March 5th, 1800, the first child of Samuel Blake Norman and Fanny (nee Thompson). For many years his father was the town’s doctor and at the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century Samuel owned several parcels of land in, what was later, the lower Chapel Street and Station Road areas, and eastwards from there to the Erewash Canal. Some of this he had acquired from his wife’s maternal grandfather, George Allen (c1718 -1801), the Vicar of St. Mary’s Church. Other parts of his estate were Spicey Close and Northfield Close, and Slade Close (aka Burrows Intake).

Nottingham Review (January 26th, 1816)

In March 1825 Samuel put parts of his estate up for sale as ill-health was forcing him to leave the area (or had he already left ?), The sale included a substantial house, with four rooms on the ground floor, two pantries, a cellar, five lodging rooms, two closets, with a soft-water cistern. Also an excellent garden, large well-stocked orchard, a newly-built stable, coach house, cow houses and pasture, down by the Erewash Canal. It appears that this sale was unsuccessful, as the property appeared once more at an auction in August 1830.

Samuel died at Swansea, Glamorgan on February 10th, 1842.

Adeline remembers that “Dr. George Blake Norman lived at Dalby House. He was born in the old house in the field below the Park, leading on to the present Station Road. He married Miss Potter, sister to the late Samuel and Philip Potter, the noted cricketers.

“The doctor made several alterations to Dalby house, as well as enlarging it. The surgery, which was in the yard approached from Anchor Row, was a dark, cheerless room. When I have gone sometimes on Thursday morning for medicine I have seen women sitting on forms round the surgery, waiting for Dr. Norman, who was the Public Vaccinator, to vaccinate their babies.

“Dr. Norman always rode on horseback when visiting his patients.”

George Blake Norman was born in March 1800, son of surgeon Samuel Blake Norman and Frances (nee Thompson).

He studied medicine in London and Paris before qualifying in 1822, from which year he practised at Ilkeston.

In October 1841 he married Sarah Potter, eldest child of coal-master and farmer Samuel and Sarah (nee East). His brother-in-law, the Rev. Robert Morgan Jones, Incumbent of Cromford, officiated at the wedding.

In 1843 George was re-appointed as Medical Officer for the Heanor District of the Basford Board of Guardians, at an annual salary of £42.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

The children of George Blake and Sarah Norman

Adeline tells us that “Dr. and Mrs. Norman had several children”. In fact they had ten children.

The first identified by Adeline is “Allan, the eldest, who was a doctor. He married Miss Mason, ward of the Rev. James Horsburgh, who was at that time Vicar of St. Mary’s. They went to live at Monmouth, and I believe Mrs. Allan Norman died when her first baby was born. “

The oldest child was physician and surgeon George Allen Norman (1842-1910) — perhaps named after his great-great-grandfather and Vicar of Ilkeston and Kirk Hallam, George Allen (c1718-1801).

In March 1866 he was awarded a B.A degree (Honours) at Oxford University, in December 1867 obtained the diploma of Bachelor of Medicine from the same university and shortly after began to work with his father at Dalby House.

On August 30th, 1871 he married Anne Elizabeth Mason, the daughter of farmer and land agent Charles Adnum Mason and Anne (nee Edwards). In 1849 her mother’s sister Amelia Edwards had married James Horsburgh who was Vicar of St. Mary’s Church (1863-1873).

Anne Elizabeth Norman died in Monmouth just over a year after her marriage and in February 1875 George Allen married his second wife, Mary Emma Moyle Smythe, daughter of army major Frederick and Ellen (nee Johnson).

In 1879 a report circulated through Ilkeston that George Allen and his wife had been ‘lost at sea’ on their way to New Orleans when the steam-ship ‘Memphis’ sank, with the loss of all its passengers. The ship had indeed been wrecked off the coast of Spain, near Corunna, but with no loss of life.

—————————————–

“Blake, the second son, was also a doctor, and was assistant to his father. He married his cousin Florrie Potter, of the Park, youngest daughter of Sam Potter, the cricketer.”

Like his elder brother, second son Alfred Blake Norman (1849-?) spent several years of education at Rossall public school at Fleetwood, Lancashire.

From Dalby House he served as a general medical practitioner and later as medical officer for the Ilkeston District of the Basford Board of Guardians, a post which he held until the end of 1874 when he left the town. (His position as medical officer was then taken by Thomas Arthur Crackle).

Alfred’s marriage to Florence East Potter, second daughter of Samuel and Ann (nee Streets) and therefore his first cousin, on February 2nd 1875, was conducted at St. Mary’s Church by the Rev. Alfred Potter, Rector of Keyworth and uncle to the bride and groom.

Dated on the day of their marriage was an Acrostic written by Edwin Trueman of the Ilkeston Pioneer.

No happier bridgroom and his bride

E’er trod our Church’s aisle,

Or pledged their solemn loving troth,

Beneath that staely pile.

Revered by all, ‘mongst ev’ry grade

In all the ranks of life,

May Heaven protect beneath its wings,

The husband and the wife;

And grant that they who bear the name

Which lives in ev’ry heart,

Ne’er may receive in Fortune’s round,

Adversity’s keen dart.

Prosperity, gild thou their path,

And radiant sunbeams shine

On those whose deeds long outlive

The loudest praise of mine.

“Through all the changing scenes of life”,

May blessings shower upon

“Two souls with but a single thought,

Two hearst that beat as on !”

Ecstatic then will be their bliss,

And joy beyond compare

Reign in the hearts of those who make

Affection’s dwelling there.

After a honeymoon in Paris the couple made their home at the Market Place, Oakham, Rutland where Alfred Blake served as a general practitioner.

—————————————–

“Reginald and Everard, the two youngest sons, went one evening to bathe in the Open Hole at Stanton; Everard was seized with cramp and was drowned”.

Not present at Alfred Blake Norman’s wedding in 1875 was his younger brother, by two years, Everard (1851-1871).

About a mile and a half from Ilkeston and formed from ironstone excavations on the estate of Colonel Newdigate, ‘Open hole’ at Kirk Hallam was a large pond with a depth of up to 100 feet at its centre, a popular bathing place with several private families in the area.

Everard Norman, almost 20, and his brother Reginald, 17, had often been there and were there on Wednesday afternoon, August 9th 1871, with three friends, the sons of the Rev. James Horsburgh, Vicar of Ilkeston.

It seems that Everard was swimming from the bank to reach their boat which was out on the pond, when he became disorientated and sank into the water. James Macdonald Horsburgh was alerted by the cries of his younger brother Lee who was in the boat, and from the far side of the lake he dived in and swam over to Everard, reached him but was then himself pulled under the water by his struggling friend. The two became separated and only James Macdonald reached the surface. Everard had disappeared.

The search for him continued frantically with further fruitless diving and with local people now joining in. Finally the pond had to be dragged but it wasn’t until midnight that Everard’s body was recovered and taken to Dalby House.

At the time of his death Everard was studying at Lincoln College, Oxford, and the Pioneer described a young man “gifted with excellent abilities .. most commendably industrious in his studies. His character was such as to secure the admiration of all who knew him, and his pious and thoughtful habits such as afford great consolation to those who have to deplore his early death… he would in all probability have proved a useful minister in the Church of England”.

P.S. A similar tragedy occurred over 20 years later at Chadwick’s Open Hole at Stanton. Two young brothers, Gerald Henry Longdon and Ernest William Longdon, had come down from Durham to visit their cousins Geoffrey and Arnold Longdon, sons of J.A. Longdon, the manager of Stanton Iron Works. On a cold Sunday morning in September, 1894 the four lads went for a swim in the open hole. Gerald Henry got into severe trouble and disappeared from view. Despite the efforts of the others, they couldn’t find him and his body was only recovered some time later, when a professional diver searched the water. He was 23 years old.

“Mr W. Campbell, the toll bar keeper, made an acrostic on Everard which was printed in the local paper”.

Once more, ‘humble Ilkeston bard’ William Campbell was moved to verse, his poem appearing in the correspondence section of the Pioneer a week after the accident.

An acrostic is a poem in which the first letter of each line spells out a word or message. (We can learn much from contemporary poetry — about the writer, the subject, and the audience ??)

Mysterious change ! most painful to relate !

Pity young Everard met with such a fate!

Compassion bids me touch those tender strings

Which bind our hearts so close to men and things;

Those stronger chords, which form each kindred tie,

Are strangely cut, and yet we know not why;

What the design no mortal here explains,

While reason rules, or GOD his right maintains.

The Great I Am! earth trembles at His nod:

None to perfection ever found out GOD.

His ways are hid, obscure in waters deep,

Down in the sea, or on the rocky steep,

Or in the bosom of that peaceful lake

Where Norman slept, no more on earth to wake.

Calm and serene, down in the deep alone,

Himself unknowing, not to GOD unknown;

An earthly child, beneath His heavenly care

Down in that deep, the eye of GOD was there.

Then be it ours, since we must stand our lot,

To learn to trust HIM, where we trace HIM not;

And while with others we his blessings share,

Let us in friendship feel each others’ care;

Mindful through life a tender heart to keep,

So shall we learn to weep with those who weep;

Deeply regret this sad bereavement here,

And freely shed the sympathetic tear,

Love and compassion both together blend

For such a son, a brother, or a friend

Mourners may wear the livery of death,

Sorrow in hope, and sigh with every breath,

Fountains of tears a thousand eyes bedim,

Yet all the world is nothing now to him.

—————————————–

Everard’s younger brother Reginald (1854-1894) qualified as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons and a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians and subsequently married Matilda Ruth (nee Beardall) on April 14th, 1883 at Manhattan, New York.

They spent some time in the United States and daughter Mary Ruth was born in April 1885 at Longwood, Orange County.

About 1888 the family returned to England to live in the Skegby area of Sutton in Ashfield. By that time Reginald had been through one of the Cape campaigns, had acted as doctor on a liner between India and China, and practised in Denver and Florida.

He and his family were about to go on another voyage when Reginald died at Sutton in Ashfield on March 26th, 1894, aged 39. His widow then remarried to Robert Voss, town clerk solicitor in Bethnal Green, London.

—————————————–

“Edith was the youngest child”. Edith (1859-1883) was the eighth child and died at Oakham, Rutland, aged 24.

—————————————–

“There had been other children, one girl, I think her name was Constance, died in an epidemic when about sixteen years old”.

There was no Constance; this was probably Sarah Jane (1841-1857) the oldest daughter, who died from bronchitis at Dalby House in 1857, aged 13.

Eleanor Gertrude (1846-1848) and Cecil Mompesson (1857-1858) both died in their second year.

Nigel Downes is curious about the name given to son Cecil: “Mompesson is an unusual name, used here as a Christian name. I’m aware it is the surname of the Vicar who was at Eyam during the Plague and moved to Eakring“. His subsequent research led him to establish that “William Mompesson (1638-1708) Vicar of Eyam who arranged for the isolation of the Derbyshire village of Eyam during the plague, (later Vicar of Eakring in Nottinghamshire) was Dr George Blake Norman’s Great, Great, Great, Great Grandfather”.

Youngest siblings Arthur (1861-1862) and Marian (1864-1866, whooping cough) both died in infancy.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Later life

After the birth of the seventh child Dr. Norman and his family could be found taking a holiday at Bangor House, Church Walks, in Bangor, North Wales with wife Sarah’s brother, the Rev. Alfred Potter.

And here Adeline’s recollections may be suspect. She recalls that “Dr. Norman was the first chairman of the Local Board, and at one of the meetings, held at the Cricket Ground Chapel, a quarrel arose, and a free fight took place outside the chapel. It was a sad sight to see men holding prominent positions fighting like savages. The next morning the townspeople were shocked to learn that Dr. Norman had been seized with illness. He was incapacitated and never again followed his profession. It was always thought that the stroke was caused by the disturbance of the previous night”.

Adeline may be conflating two separate incidents when she recalls Dr. Norman’s incapacity.

As we have seen (the Local Board’s formation) the doctor was involved in the 1864 fracas at the Cricket Ground Chapel when the size of the Board was agreed. However he suffered a paralysis affecting his left side in 1869 just as he was to supervise the vote-counting at the annual election of six officers to the Local Board. This was at the time when the Board was meeting at the new Town Hall and not at the Cricket Ground Chapel.

A letter dated July 29th 1869 and written to the Local Government Office by John Wombell, as Clerk to the Board mentions that “the gross insults the Chairman met with yesterday from the partisans of certain candidates have doubtless mainly contributed to his affliction — a severe attack of paralysis”.

It appears that once more Dr. Norman’s character had been impugned and he had been insulted about his preparations for the election; Messrs Carrier and Sudbury were among those responsible, according to the Clerk.

His incapacity led to Dr. Norman’s resignation as Chairman three weeks later.

“Dr. Norman and his family left Ilkeston sometime later”. In fact it was at the end of September 1872 that he left his post as Registrar of Births and Deaths to be replaced by George Barker. Then with his family Dr. Norman left Ilkeston for ‘The Poplars’ in Manton near Oakham, Rutland in 1875.

From his appreciative patients he received a beautifully framed illuminated address. Funds raised subsequent to his departure were sufficient to purchase an elegantly chased silver candelabrum, bearing the inscription …

“Presented to George Blake Norman, Esq., by Ilkeston friends as a token of esteem and affection. February, 1876”.

Three months later the doctor was fêted by members of the Marquis of Granby Lodge of the Ilkeston and Erewash Valley United Order of Oddfellows for whom he had been the medical attendant for more than 30 years, and he was presented with ‘a very handsome testimonial’ or address, signed by Samuel Streets Potter, Herbert Brentnall Chadwick, Henry McDonald and John Parkinson Mee.

“The address was beautifully designed and written by R(ichard) T(homas) Mounteney, Fletcher Gate, Nottingham, on illuminated vellum, and framed in Alhambra gold, by brother I(saac) Cordon, Bath-street, Ilkeston, on whose workmanship and finish, it reflects the highest credit” (IP May 1875)

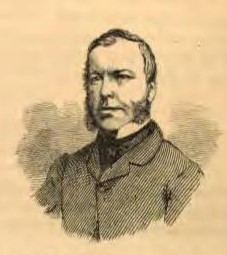

George Blake Norman died at his Rutland home on February 1st 1877, aged 76.

His wife Sarah died there on November 22nd 1880, aged 58.

Both were buried in the family vault in St. Mary’s churchyard, near the east chancel window of the church.

The Norman family tomb at St. Mary’s Church

Commemorated at the tomb are seven of the children and the parents.

“Without doubt, no man was better known in and around Ilkeston than Mr. Norman. He was a native of the town, and practised in it as a surgeon for about fifty years, during which time he won the esteem and affection of all with whom his duties brought him in contact. He has occupied many important positions in the town, and was noted for his earnestness in any good and philanthropic work. As a thorough Churchman and a staunch Conservative he has done good service to the Establishment and to his political party, and but for his death having been preceded by several years of inaction, owing to illness which had been brought on by excitement during a parochial election, his loss would have been severely felt. For many years he was Chairman of the Local Board, and indeed he occupied that office from the formation of the Board until seized by the illness above mentioned. He was also churchwarden for a long period” (NG)

The Norman Family was “of Danish extraction, and therefore of great antiquity, as ‘Burke’s Landed Gentry’ mentions the family at great length, and traces its ancestry to the time of Edward the Confessor”. (DM)

In May 1881 the Trustees under the will of George Blake Norman put up for sale his Ilkeston estate.

This included the ‘commodious and pleasantly situated’ freehold family residence of Dalby House, including stables, large gardens and an adjoining close of pasture land of almost four acres.

Also included in the estate were ..

….. a farm house with garden and orchard, nine cottages with gardens along Cotmanhay Road, and pasture land.

….. premises and land along the south side of Station Road some of which was occupied in 1881 by brick manufacturer Samuel Shaw. Also a dwelling house and garden on the south side of Station Road, occupied by Samuel and extending back to Chapel Street. (see Beyond North Street).

…… a Mill with attached house, gardens, stables and outbuildings, two workers’ cottages, meadow land fronting up to Station Road and part of which was soon to become Mill Street.

….. also building land in this area and along both the north and south sides of Station Road.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Other members of the Blake Norman Family

The only daughter of Samuel Blake and Fanny Norman was Fanny Blake Norman, born in 1805 at Ilkeston. On July 27th, 1841 she married the Rev. Robert Morgan Jones and eventually settled in Cromford, Derbyshire, where Robert was vicar at the parish church and the Rural Dean of Ashover, and where their only child, Fanny Norman Jones, was born in 1843.

Fanny Norman Jones, a spinster, died at Cromford on August 8th, 1884, aged 41. At the burial her father led the mourners but her mother was notably absent, having been ill for some considerable time. And on October 9th, 1884 she too died. Just as with the previous burial ceremony, every place of business within the village community was closed and all curtains were drawn, and once more the Rev. Robert was chief mourner.

Robert later retired to the Dimple in Matlock where he died in October 1895, aged 89.

(to be continued)

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Henry George Brigham replaced Dr. Norman as medical officer for the Granby Lodge on Dr. Norman’s retirement and it is to him that we now turn.