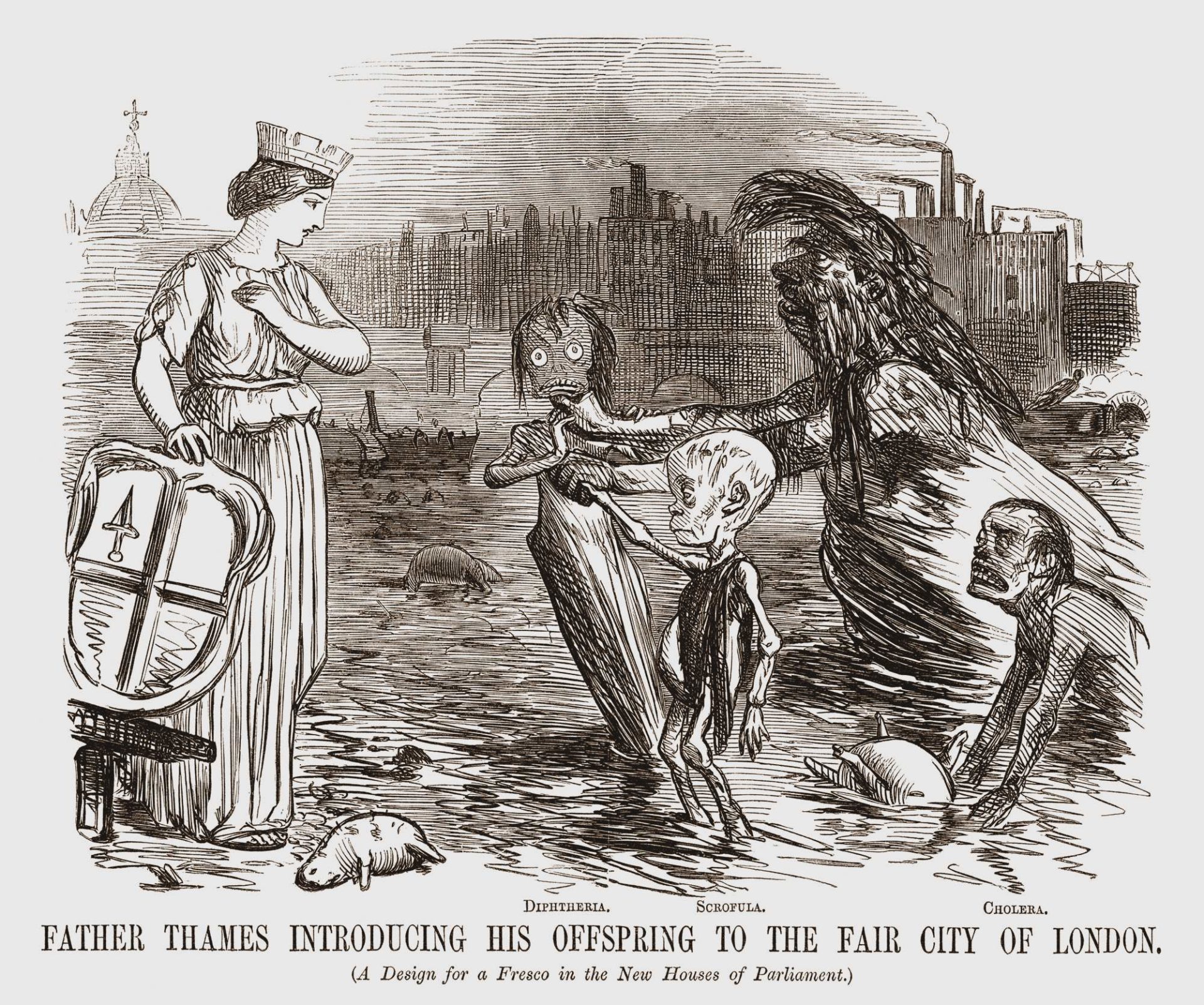

Connected with Ilkeston’s water supply, Adeline recalls the deficiencies of Ilkeston’s sanitation system.

“The drainage of the town was a very primitive affair. True, there were grates in the streets, but as there was no carrying water, anyone going through the streets after the midday meal, especially on Sunday was assailed by the unpleasant smell of cabbage water, etc. But people were glad to have this way of drainage, inefficient as it was, rather than the old cesspools.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————

The Buchanan Report of 1870

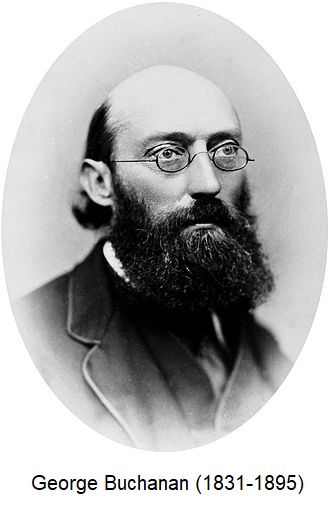

In 1870, in connection with a fatal epidemic of scarlatina, which in the previous year had caused 81 deaths, and the prevalence of enteric (typhoid) fever, the inspector for the Medical Department of the Privy Council George Buchanan produced a report on the Sanitary Condition of Ilkeston.

He discovered that ‘excremental pollution’ was widely diffused in the water of the town and cited ‘ill-kept roads and unclean channels’, overflowing ashpits with filthy refuse, and pig-styes far too close to cottages.

(See Mrs. Joseph Scattergood).

His complaints were many …

There is no place in the town to which persons, other than paupers, could be removed to prevent the spreading of contagion. ….

In my not small experience of stinks, I have never met any to surpass the privies and ash-pits of Ilkeston. There are no public arrangements for attending to the same….

There is a certain sort of drainage in the town, by brick and pipe drains … but open brooks and ditches carry pollution to the Erewash Brook and Canal …..

The drinking water is both from private and public sources. Private wells vary in purity. The public water supplies are given by the Ilkeston Waterworks Company and are from two sources. The one at the south end of town is a special water shaft, 140 feet deep, into coal measures, yielding 17,200 gallons daily. The other, on the north side, consists of drainage from a working coal-pit. The supply is constant in winter and for 12 hours daily in summer.lEss than half the houses get the Company’s water. As for quality, the water at the south end is good, except for excess of mineral in it. That at the north end is very bad, with excessive impurities. It passes from the pit pumps to two smaller tanks. with an abundance of frogs and newts in them. It is then strained through large gravel blackened with a little burnt wood, to which a magical efficacy — for it can have no physical or chemical effect — appears to be attached. The gravel keeps out bodies of larger animals from the supply pipes.

Thus it appears that in air and water there is in Ilkeston widely diffused pollution. … (and) there is no-one with the function of an Officer of Health. The Local Board has one officer who combines in half his person the function of Surveyor, Inspector of Nuisances, and Rate Collector. He has 2500 collections to make in 156 days. Of systematic inspection, there is absolutely no trace whatever. (In 1870 Joseph Scattergood was this person and look what a mess he got into !!)

In other words, Ilkeston needed an isolation hospital, improved disposal of night-soil, better and closed sewers which didn’t empty into local water courses, and a more widespread water supply, better filtered and offered to more, by the Local Board. Compare this with the recommendations of the Blaxall Report of 1881 (below) and see how much progress was made in those ten years !!

However, this is not to say that the Local Board didn’t bother to respond to the Buchanan Report, nor try to put its recommendations into effect. In 1872 the Board approached the Duke of Rutland (via his agent Robert Nesfield), asking for the use of farmer Robert Noon’s clay-hole at Gallow’s Inn — Robert being a tenant of the Duke. It was needed to ‘store’ night-soil. The agent initially refused the request, especially as he wasn’t sure where this site was. This followed a similar refusal from Messrs. Potter for the use of land at the top of Grass Lane (Norman Street), and for the use of an old brickworks on Awsworth Road. The Board was trying !! But so far, the only night-soil depot was down Derby Road, on a piece of land belonging to the Attenborough family.

Some effort was made to improve the system of drainage too. For example, in the Spring of 1873 the Local Board Surveyor was asked to prepare plans for an improved drainage in the North Street area (known locally as Pigstye Park) though an illness to Thomas Shaw, one of the principal property owners in the area, thwarted immediate action and problems continued therefore.

However, in 1872 and 1873, when several cases of smallpox were discovered in the town the Local Board revealed its weaknesses once more. No households were isolated, drainage was still very imperfect, and inhabitants continued to throw stinking refuse into open channels and streets (according to the Pioneer’s letters column whose mysterious contributors were always eager to have a go at the Board !!). And as the smallpox outbreak continued into the next year, officers of the Local Board went to inspect a covered cart, belonging to draper Charles Woolliscroft, to ascertain if it might be converted and used as a temporary hearse, or to convey patients to the Basford workhouse. Perhaps some action more far-sighted was needed ?

There were continued examples of bad practice in the town. In 1875 an outbreak of typhoid fever occurred in Sisson’ Row. The residents got their water from a well which was found to be contaminated by leakage from the nearby privies. The Inspector of Nuisances recommended that the sewer drains there, going to the main drain, should be relaid but deeper, and this time the appropriate action was taken.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Street scents and disease.

Small pox had visited Ilkeston on several occasions in the early Victorian era. For example in the second quarter of 1845 the town recorded an above-average number of deaths from the disease — 74. The disease then reared its ugly head again in England in the early 1870’s. Perhaps this is what inspired a letter to the Pioneer, written by young Albert Moss, a pharmaceutical chemist and son of John Moss, the pawnbroker of South Street. Albert wrote of the use of disinfectants, particularly Chloride of lime (bleaching powder), either dissolved in water and then stood in rooms as a fumigating ‘perfume’, or sprinkled as a powder on floors. Neither of these methods of use was attractive to Albert.

For him the best method was to dissolve a pound of the powder in two gallons of water, leave for twenty four hours, shaking occasionally. Thereafter rags should be soaked with the liquid and then hung as high as convenient — to infest the room with the smell of chlorine. For drains and cesspools, sulphate of iron or ‘green copperas’ would be suitable to fulfill its purpose. In all cases the aim was to eradicate smells.

And it was shortly after the smallpox outbreak of 1872/73 — in May 1873 — that the Pioneer returned to one of its popular themes – ‘have a go at the Local Board members’.

The newspaper believed that the actions and premises of several members of the Board were responsible for some of the more foul smells bedevilling the town at that time – smells which the Board was conveniently overlooking.

“STREET SCENTS, as patronised by members of our Local Authority, are becoming quite fashionable and noteworthy, on the approach of summer days and sunny weather.

“Houses have for some time past been pretty well fumigated with strong scents by the illustrious sub-medical officer (Dr. Robert Wood) and sub-inspector (Woolstan Marshall), with a view to prevent the spread of disease. The streets, it appears, are to undergo a different process, under the management of certain members of the Board, uncontrolled of course, by the Medical Officer, Surveyor, and Inspector of Nuisances. The scent most approved is produced by a concentrated mixture of house refuge and slops, and pig and stable manure, which is carefully deposited on the causeways, in the channels, and on the carriage ways in the Market-place, Bath-street, and other chief thoroughfares of the town. The delightful fragrance of this mixture is most frequently scented near the residence of some members of the Local Board, and generally at mid-day, when people are going to or returning from the factories, or taking their evening walk. The right of these particular members to monopolise the distribution of this scent in their respective localities is spiritedly preserved and patronised, and attempts to create the same sweet fragrance in quarters not inhabited by members of the Board, are promptly repressed and the parties punished or threatened with punishment.*(below)

“Many ratepayers have an idea that these scented muckheaps in the town streets do not emit a very pleasant odour, and are not less hurtful to the public health than the pigstyes and cesspools in the gardens of the poor, about which the richly-paid officers of the Board indulge in much tall talk, and to suppress which, the iron fangs of the law are often needlessly applied.

“When and wherever street scents are patronised by members of the Board, it might not be amiss if the said members would place themselves in the centre of their mixture, and there remain until its sweetness has fully evaporated”.

* For example, see what happened to John Woodroffe in Mount Street. And you could have a look at how Local Board member Solomon Beardsley’s Burr Lane pig sties might have been a target for the Pioneer.

In 1874 the Local Board announced the ‘discontinuation of free removal of night soil’.

It would no longer organise the emptying of privies, privy cisterns, ashes pits, etc. gratuitously as heretofore. Householders could now do this independently or apply to the Inspector of Nuisances who would organise removal for a fee.

Perhaps this is what led one resident of Lee’s Yard (or Albion Place) to take matters into his/her own hands at the beginning of 1875. That resident emptied the contents of a cistern into the street, contents which had been allowed to fester there for several weeks !! The furious Pioneer was quickly ‘on the case‘ of course…. “a stinking unsightly mess of night-soil — the ground all around saturated with its reeking contents. The filthy state of that yard … is a disgrace to the Local Board…. a pity that we have not got a Government Inspector from the London Board .. to prosecute the Local Board for neglect”.

However one was shortly to arrive !!

In June 1879 there was another outbreak of enteric fever in Ilkeston, followed by one throughout 1880, with a total in that year of 191 cases and 17 deaths.

In July 1880 a resident in Station Road wrote to the Local Board, stating that he and his wife had both been exceedingly ill recently and blamed this on the bad smell caused by the blocking of a sewer near to his house. To support his claim he enclosed a medical certificate stating that the unsanitary condition of the neighbourhood had certainly caused his illness, but the writer’s claim for compensation – he had been unable to work for several days – were duly noted by the Board and duly ignored.

In his report to the Local Board at this time the Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Robert Wood, wrote…

“I have visited several cases of fever in the town, and in every case but one have found the grates untrapped, and I believe the foul smells from the drains are the principal cause in producing zymotic diseases, especially fever. I recommend a freer ventilation of the sewers and drains of the town”.

In November 1880 a(nother) Local Government Inquiry was held at the Town Hall, this time to consider the Local Board’s application for a loan of £12,000 for sewage works, and an additional loan of £2000 for improvements to the water supply.

At that time the Pioneer included a résumé of events so far.

- various sewage disposal schemes had been put forward in recent years.

- plans by Mr. Brundell, civil engineer of Doncaster, for yet another scheme, were recently prepared but set aside.

- the Local Board’s surveyor George Haslam had then prepared specifications for a sewage works at Little Hallam.

- land had been compulsorily purchased to accommodate the works.

- since the last Board elections in April the newly elected members called for a reconsideration of the surveyor’s scheme.

- the Erewash Canal Company has called upon the Local Board to cease the influx of sewage into its canal and asked the Board to pay for the cleaning of the canal between Barker’s Bridge and Babbington Wharf.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Blaxall Report of 1881

The Buchanan Report of 1870 (above) had made several recommendations to improve the sanitary condition of Ilkeston.

In 1881 the then inspector for the Local Government Board, Dr. Francis Henry Blaxall, produced another report in which he noted that since the previous report Ilkeston’s Local Board had “not been altogether unmindful of the duties imposed upon (it) by the Legislature. At the same time, through the want of sustained effort on (its) part the measures undertaken have not fulfilled the desired end, while there has been a total want of remedial action in respect of certain conditions which exercise a very prejudicial effect upon the public health”.

In other words, get your finger out!!

Dr. Blaxall’s report searched for the causes of the enteric fever and its spread in Ilkeston, and identified the town’s privies, water supply and sewers as the most likely sources of fever. He examined each one in turn.

Privies

“As regards excrement disposal, the privies from their extreme unwholesomeness were highly condemned by Dr. Buchanan, who advocated the substitution of earth closets for the midden privies in vogue. But no improvement has been effected in this important particular, the atmosphere in and around the dwellings continuing to be polluted by emanations from decomposing excrement stored in large pits, which serve also as receptacles for refuse”.

Middens was basically open holes leading to a cesspool, which could leak into the water supply. They were emptied by ‘night-soil’ men, employed by the Local Board who charged 1s 6d per load … the Board then sold them on at 1s per load. The charge created a disincentive for householders to have their privies emptied at frequent intervals.

In an earth closet — a form of composting toilet — excrement was covered with, and broken down by, earth and could then be used as fertiliser.

However the Blaxall report pointed out that the privies in the infected houses in Ilkeston were no different to those of healthy families in the same area or to those in unaffected parts of the town. They were all generally unwholesome!!

So they could be ruled out as a cause of the fever.

However once infected, these privies were a danger to the people using them and to the water supply which may happen to be in their near vicinity, and so could contribute to the spread of the disease.

Water Supply

The report noted that the Local Board’s three public sources of water were said to be supplying 170,000 gallons per day, to slightly more than half the town’s houses as well as to its trades. This was calculated to work out at less than 20 gallons per head for those persons using the public water supply. Altogether 1531 houses were supplied with the town water and within these houses there were 31 cases of fever spread throughout the town.

The report would not therefore impugn the town water.

The remainder of the town was dependent for its water supply on private wells and rain-water tanks.

“The (private) wells are sunk in a soil befouled of filth from privy pits, refuse heaps, and other contaminating conditions…. Further, owing to a faulty arrangement connecting these (water) tanks with the sewers by means of overflow pipes, the water is exposed to dangerous contamination by sewer air. In two or three instances … the effluvium arising from them was very offensive… while in one instance a black line indicated that sewage had found its way into the tank by means of the overflow pipe. The tank water is complained of as being very black, the people stating they can write their names with it”.

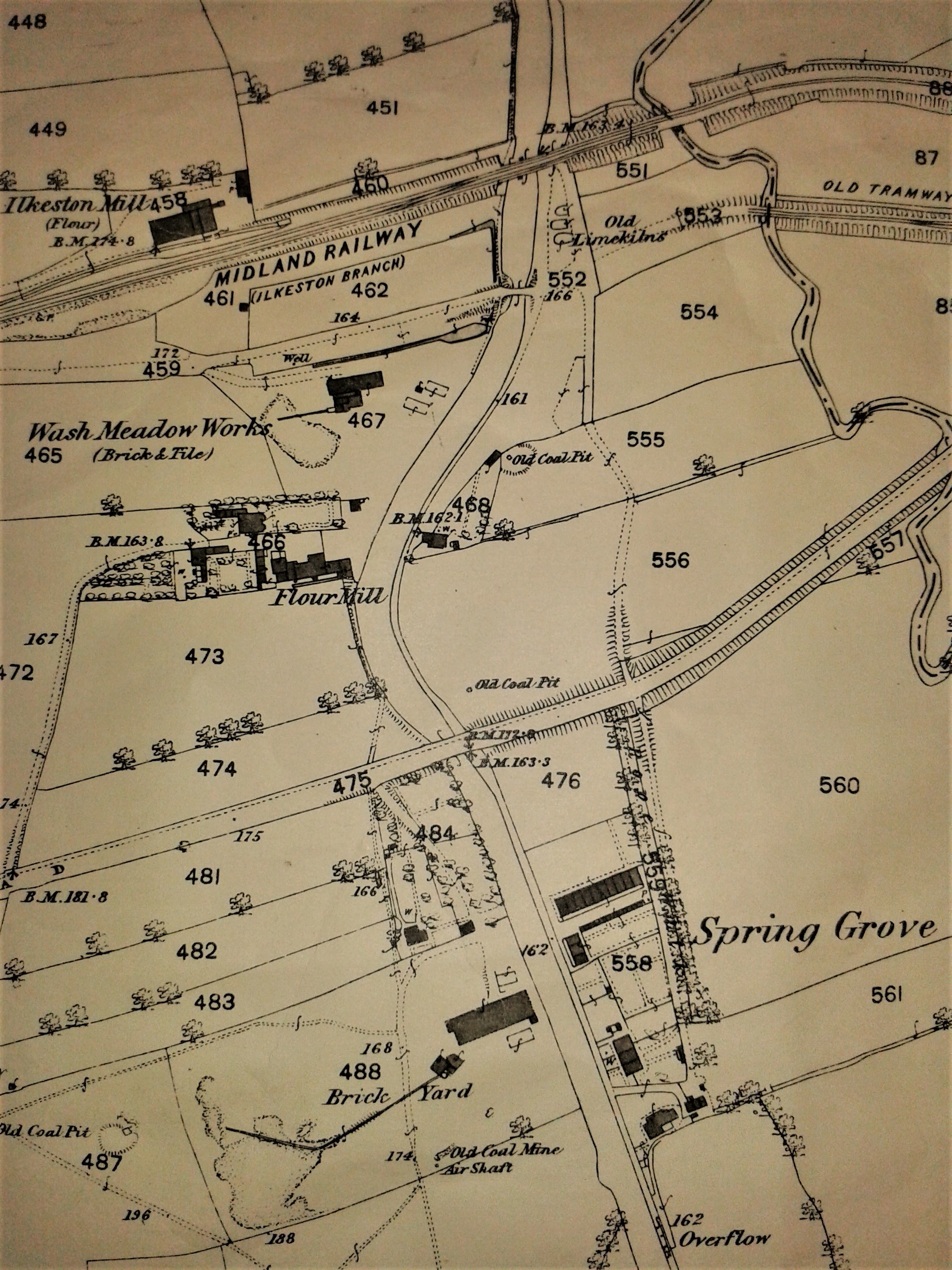

A total of 1340 houses relied on these private sources of drinking water and here there were 74 infected families, 46 dependent on wells and 28 on tanks. All the wells were exposed to pollution and one particular well in Spring Grove Terrace was used by several people who later became infected.

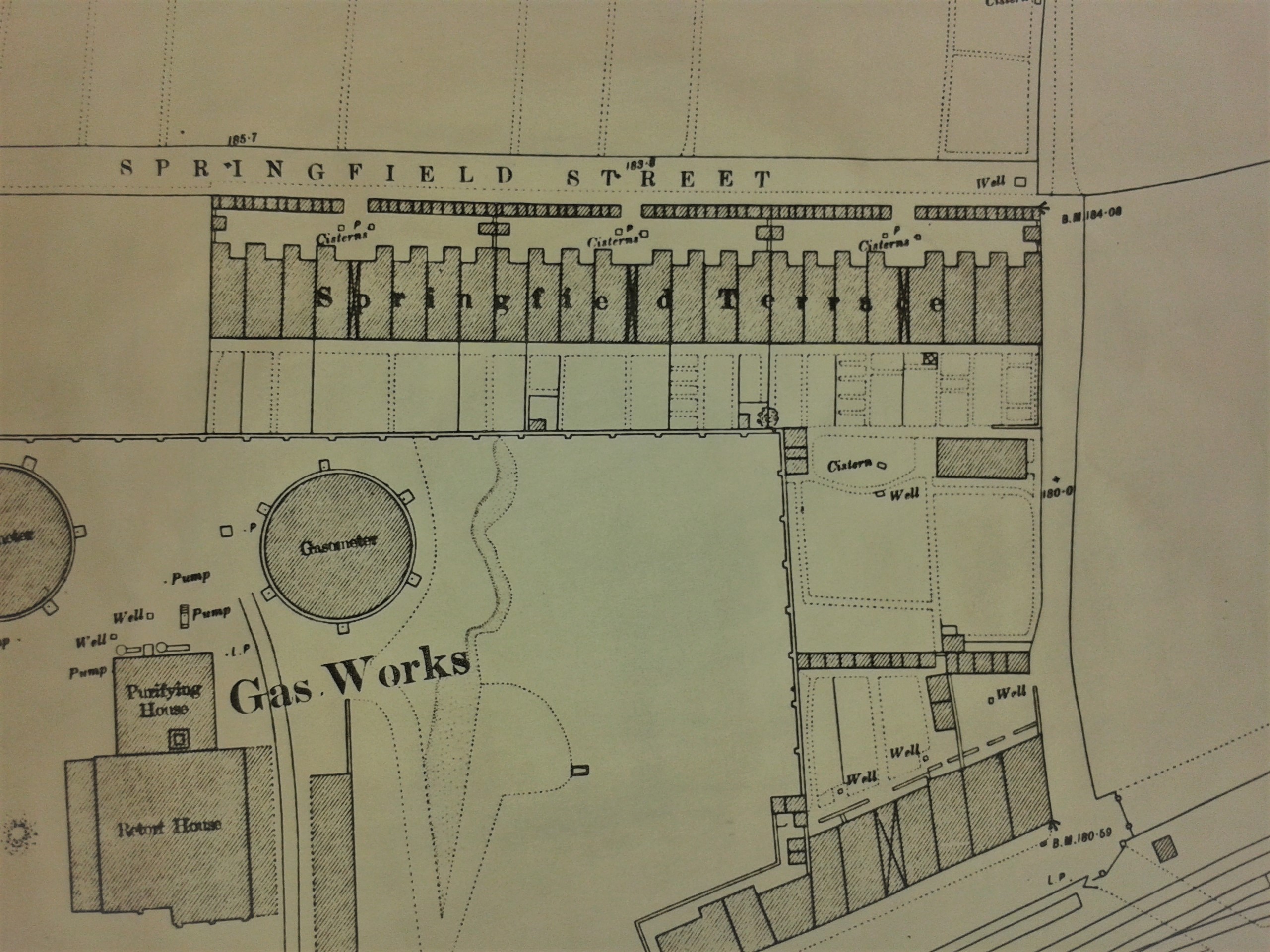

Spring Grove Terrace was a row of ten cottages, close to the Rope Walk by the canal, supplied by one well. You can see them, opposite the Brick Yard, in the map … an isolated, remote and tiny community.

Just 15 feet from the well, standing on a higher level, was the nearest privy, while a slop drain carrying the terrace’s sewage to a ditch, ran close by. In September 1880 the terrace recorded its first case of fever and in total, seven affected families suffered 15 cases of disease there. Of the seven families, six got their drinking water from the well. The remaining three unaffected families got water from other wells.

Inhabitants of houses nearby with separate privies, drainage and water supply were also unaffected.

The report’s conclusion was that the water from this particular well certainly contributed to the contagion in this terrace, though the privy and drain might also be implicated.

Attention then shifted to Springfield Terrace (map below), at the rear of the Rutland Street Gas Works, a row of 24 cottages of which 14 were affected, giving rise to 31 cases of fever. Its well was at one end of the row (at the end of Springfield Street) with a slop drain and privy pit very close by, and with surface drainage seeping into it. The well was closed down and town water was thereafter provided.

There was a similar examination of a row of cottages in Ebenezer Street. Six families had obtained their drinking water partly from a well and partly from a rain-water tank, both in close proximity to a filthy privy pit. Five of these six families went down with the fever. As the tanks had an overflow pipe into the sewer, the question as to whether the sewer air was causing the fever arose.

Sewers

“It is satisfactory to report that the (Board), after long opposition on the part of some of its members, (will) provide intercepting sewers, which, after collecting the contents of the various sewers, shall convey the sewage to land, there to be disposed of by infiltration”.

The Local Board had been given permission to obtain a loan to carry out this sewage scheme and Dr. Blaxall noted the urgent necessity for the work to be carried out without delay.

In the meantime, “the sewerage continues very imperfect and defective, and all the sewage finds its way … into the river or canal. There is no provision for the ventilation or flushing of the sewers. The heads of them are closed and the street gullies trapped, while the outlets are left open, allowing the air to blow freely up the sewers…..”

In the first half of 1880 the cases of fever were not confined around one particular sewer.

However in July and August of that year the area around Granby Street, William Street and Brussels Terrace suffered particularly. Here there were 250 houses, of which 47 were affected giving rise to 90 fever cases, many of them occurring at the same time. The rest of the town accounted for 2500 houses where only 47 families were attacked.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Report’s conclusion

The report looked for a link to account for the 90 cases of fever and found it in the infected air of the sewers.

“The simultaneous appearance of cases in different streets in a specified area around Rutland Street pointed to a common centre of origin, and the only condition to which the sufferers were alike exposed was the infected air of the sewers escaping either within or around their dwellings.”

It was also of the opinion that the cases found in Springfield Terrace were caused by infected sewer air rather than by polluted well water.

Taken from Dr. Blaxall’s Report…..

| Year | Deaths (all causes) | Smallpox | Measles | Scarlatina | Whooping Cough | Fever | Diarrhoea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 167 | 4 | 6 | 9 | |||

| 1872 | 208 | 23 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |

| 1873 | 240 | 20 | 1 | 9 | |||

| 1874 | 270 | 5 | 3 | 19 | |||

| 1875 | 300 | 2 | 35 | 8 | 7 | 16 | |

| 1876 | 285 | 13 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 23 | |

| 1877 | 241 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 13 | ||

| 1878 | 321 | 3 | 47 | 8 | 14 | ||

| 1879 | 239 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 8 | ||

| 1880 | 328 | 15 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 28 | |

| Total | 2599 | 43 | 40 | 97 | 39 | 50 | 147 |

*Note that there were no deaths from diphtheria in this decade.

From the figures in the above table, the report deduced that Ilkeston’s death rate from these diseases compared unfavourably with that of England and Wales in the same period…. and the health of the town was declining rather than improving!!

Another table showed also that the annual death rate of Ilkeston was also worse than that of 50 large towns in England and Wales.

Dr. Blaxall stated that “the increase in the mortality here exhibited is a matter for serious consideration by the (Local Board), and should impress them with the vital importance of taking immediate steps to improve the sanitary state of their district, experience teaching that a high death-rate goes hand in hand with prevalence of such preventable conditions as are met with in this town.

“With regard to the frequent recurrence of epidemic disease of a highly contagious nature, such as smallpox and scarlatina, the (Board) have made no provision in the way of an infectious disease hospital, and have thus neglected a measure of the first importance, in attempting to arrest the progress of infectious disease, with reference specially to scarlatina, to which this town is peculiarly subject, and against which there is no known prophylactic, such as that afforded by vaccination in regard to smallpox”

Dr. Robert Wood of the Market Place, Medical Officer of Health to the Local Board, had already advised the Board that such a hospital should be built, as well as suggesting the ventilation of the sewers and a more regular removal of privy contents.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Recommendations from the Blaxall Report.

- The necessity of adopting an improved system of privy accommodation by the adoption of the dry earth or water carriage principle.

- The systemic removal at short intervals of refuse and manure from the vicinity of houses.

- The use of town water instead of that obtained from wells and rain-water tanks, and especially to see that the communication between tanks and sewers no longer exists. And to increase the supply of such water.

- The ventilation of all sewers and drains, the proper trapping of drains in the vicinity of houses, and the prevention of direct communication between indoor sinks and waste-water pipes and the sewers and drains.

- Sewage should be no longer permitted to flow into and pollute the river and canal.

- The completion of the proposed sewerage works, with means of flushing the sewers.

- The provision of a hospital for the reception of cases of infectious disease.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

1880s: Smallpox in the town

In May 1882 a case of smallpox was reported in Belvoir Street and the female patient had to be taken to Nottingham Hospital, the latter institution accepting her with great reservation and complaint.

Two months later and another case of the same disease appeared in Eyre’s Gardens.

Now the Local Board decided to convert its cart sheds in Pimlico into a temporary isolation hospital, by which time the patient was ‘improving’ and didn’t wish to go to the hospital anyway!

Plans for a more permanent sanatorium at Little Hallam were now prepared and accepted by the Local Board in July 1882.

Meanwhile the selection of the premises in Pimlico as a temporary smallpox shelter had not gone down well with local residents who promptly organised an outdoor protest meeting in the Market Place.

And it was local resident, draper William Smith of the Market Place, who took the responsibility upon himself to send the crier around town announcing the meeting at which he argued that “foul miasmas would arise from the ill-constructed sewers leading to the house”.

Many also pointed out that an ‘isolation hospital’ should obviously be in an isolated spot and not in the centre of town as Pimlico was.

And it was not lost on many at the meeting that the Board members had chosen a site sufficiently well away from their own domestic dwellings!!

In August 1883 the Nottingham Corporation presented Ilkeston Local Board with a bill for £7, being the cost of admission and maintenance for the Belvoir Street smallpox victim. It was promptly paid.

A second ‘wave’ of the disease occurred in January 1888. At first there were only a couple of cases, one of which was Harry Chadwick, manager of the Samuel Robinson’s Music Hall at the Poplar Inn. He had contracted a mild dose of the disease when he went to see some juvenile ‘stars’ at Nottingham who had already come down with smallpox — Harry found out too late !! Harry also found out later that he was to be prosecuted by the Town Council when it was discovered that he had been out and about in the town when at his most infectious; the prosecution was reduced to a warning however — though others would not be so lucky !! The other, more serious case was coalminer John Wright, living in Providence Place.

When the disease claimed a third casualty — Irishman Martin Scully, a coalminer living in Nottingham Road — there were serious discussions within the Town Council about re-opening the temporary isolation hospital in Pimlico of the early 1880s. Also present at the meeting were all the local doctors — Robert Wood and John Joseph Tobin of the Market Place, Joseph Carroll of Bonsall Place, Harry Potter of Bath Street, and Robert Wilkinson of Cotmanhay .

The dangers were not as great as the outbreak suffered in 1872 and 1873 — all the present cases so far were mild — but several councillors were loath to take chances. An isolation hospital was needed !! So it was decided to erect a temporary wooden building on an exposed and isolated site of Corporation land at Little Hallam, at the junction of what was (later) Quarry Hill Road and Longfield Lane. Designed by the Borough Surveyor Henry J Kilford, it was to be large enough to accommodate ten patients, five of each sex — though that number could be increased in an emergency. The residents of Little Hallam were not amused !! — they conveyed their displeasure via a letter to the Council. The Council responded by agreeing to apply to the Local Government Board for a loan of £1000 to build the ‘offending‘ structure — so sod the Little Hallamites ?!

By the first week of February 1888 the number of smallpox cases had risen to 11, including Alderman Henry Clay’s son, Henry junior, at the Mundy Arms. Another member of the Council, Samuel Robinson, was fending off accusations that his music hall manager had introduced the disease into the town –“it’s a lie ! it’s a lie” he claimed. And before the temporary hospital could be built, a 21-year-old coalminer, Thomas Martin Wate Mellor of Chapel Street, died from the disease. He was buried the following day in St. Mary’s graveyard. And his wife of less than two years, Harriet (nee Walker), was taken to Basford Workhouse, suffering from the disease.

A few more days later and with the isolation hospital almost at completion, there was another death — an infant of three months in Victoria Street. By the end of the month Henry Kilford’s wooden structure was in operation and two existing sufferers were moved out of their homes into the hospital. They were quickly followed by a sister of Thomas Mellor, the hospital’s first fatality.

None of the patients received into the hospital were asked, beforehand, whether they were in a position to pay for their treatment — it was not thought appropriate. However it was then discovered that none of the three could afford to pay and nor could their friends or family. The Council Health Committee therefore sent a ‘begging letter’ to the Basford Board of Guardians, asking if they would cover the expense. The letter was received favourably, though the Guardians would not pay for any patient who was not a pauper — if they didn’t pay then they would be sued !!

By March 20th 1888 the Town Council was able to announce that Ilkeston was now free of the smallpox disease. Though that was not quite the end of the matter.

A year later Dr Joseph Carroll, now the Medical Officer of Health for the Council, presented his report for the year 1888 — and included within it were some inflammatory remarks about Samuel Robinson and his role in the spread of the smallpox disease. Samuel threatened legal action against the doctor if the report was published with the remarks included. It was thus decided that these ‘personal details‘ should be excluded — anything for an easy life !! At the same meeting the positions of the master and matron of the infectious disease hospital came under review; most councillors now thought them superfluous and thus a drain on the Council’s finances, though Charles Mitchell (who else !!) expressed a wish to keep them employed. Eventually, both employees were either to be ‘let go’ or retained ‘at a reduced sum’

A Cottage hospital.

In the early 1880s injured persons in Ilkeston were still being transported, over rough roads, to be treated at Nottingham or Derby hospitals. Then in February 1884 a Town Hall meeting discussed the desirability of building a Cottage Hospital at Ilkeston. This was supported by Drs. Henry Potter of Wilton Place and James Frederick Digby Willoughby of Dalby House. Opposing it were Drs. Robert Wood of the Market Place and Charles Alfred Cooper of Bonsall Place who both thought that the hospitals at Derby and Nottingham were sufficiently near as to make the need for a local hospital unnecessary.

Those at the meeting decided to form a committee — what else!! — the purpose of which was to identify a suitable site where a local hospital might be built.

By the end of August 1884 a couple of cottages in Station Road were fitted up and ready for the reception of patients, so long as there were not more than ten of them at one time!

The premises were owned by John Wilson, a shoemaker, who lived in an adjacent property, and the Local Board agreed to pay 13s per week in rent for the hospital accommodation.

In 1886 a Building Fund account was set up, in the hope (expectation ?) that a larger and more commodious property with much better facilities could (would ?) be acquired.

Meanwhile, in its first three years of the Station Road premises, 128 in-patients were treated and 168 out-patients, nearly all completely cured. However in 1887 three patients died, one of them being four-year-old Alfred Henry Eaton, son of coalminer Alfred and Eliza Ann (nee Beardsley). The lad had been bitten by a stray dog, developed head and abdomen pains, and was initially treated as an out-patient. His condition worsened; he turned black and began to foam at the nose and mouth. Shortly after this Alfred Henry died. The cause was determined as blood poisoning occasioned by the dog bite.

However, at the end of those first three years, although the Cottage Hospital was becoming increasingly ‘popular’, its income was declining while its expenditure was increasing — not a healthy state of affairs. The scheme for a new hospital building was deferred once more, and a new three-year lease was taken out on the existing building. This served as ‘Ilkeston Hospital’ until March 1894 when a new one was opened in Heanor Road.

By the time of its closure, the old institution had treated 462 in-patients and 1559 out-patients.

Throughout its ‘life’ Miss Martha Alice Dean, native of Ilkeston, was the matron; Dr. Robert Wood was its consulting surgeon and Dr. Harry Potter was a serving doctor there.

In 1893*, Mr. E.M.Mundy. J.P., of Shipley Hall, generously offered a splendid site worth £800, on the west side of Heanor-road; and subscriptions came in so rapidly that the new hospital was paid for by the time it was completed.

In November 1893 the chairman of the Hospital Committee, Councillor Charles Maltby, received a generous cheque of £100 from the Duke of Rutland towards the building fund. Local collieries had also given or promised donations such that the hospital was then on the way to being debt-free.

Both the laying of the foundation stone by Mr. Mundy**, on April 26th, 1893, and the opening by Lord Belper, on Feb 28th, 1894, were celebrated by a general holiday, and witnessed by many thousands of people. The main streets were decorated with flags, and that near the site by triumphal arches of evergreens. Processions, headed by the brass band and the volunteer Fire Brigade, and including the Mayor and Corporation, the local magistrates, clergy and ministers, the Mayoress, and many others in carriages, paraded on the first occasion to the site and on the second to the completed building. The collection at the former ceremony realised £135 16s 1d, and the latter £125; and the working classes “exhibited extraordinary zeal and energy,” as Mr. Mundy remarked in his speech. A public luncheon and a public tea were held after the two ceremonies. The hospital was built by Mr. W.E. Shaw***, of Ilkeston, of Shipley and Gallows Inn local red-faced bricks: the stone is ‘Farley Darley Dale’, the roof covered with brown Broseley tiles. It contains 26 beds, an operating room, matron’s room and nurses’ room. &c. (from Trueman and Marston)

*It was in fact in March 1892 that A.E.M.Mundy offered a site for the new hospital.

**The Duke of Rutland had originally been approached to lay the foundation stone.

*** George Andrews was responsible for the hospital plumbing.

Above, Ilkeston Hospital in Heanor Road 1894 (from Trueman and Marston), and below, the hospital in 1902.

The plans (from which the above drawing was taken) were drawn up, free of charge, by Charles William Hunt, A.R.I.B.A. (Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects), of Station Road.

By the end of 1894, at the hospital’s annual general meeting, it was reported that one out of every 45 of the town’s population had been treated at the hospital. There was still £100 outstanding from the promised subscriptions of the previous year, though the building fund still had a £75 credit.

By July 1899 an isolation ward had been added to the hospital, at a cost of £400 .. the whole amount having been raised by a gymkhana in the previous summer.

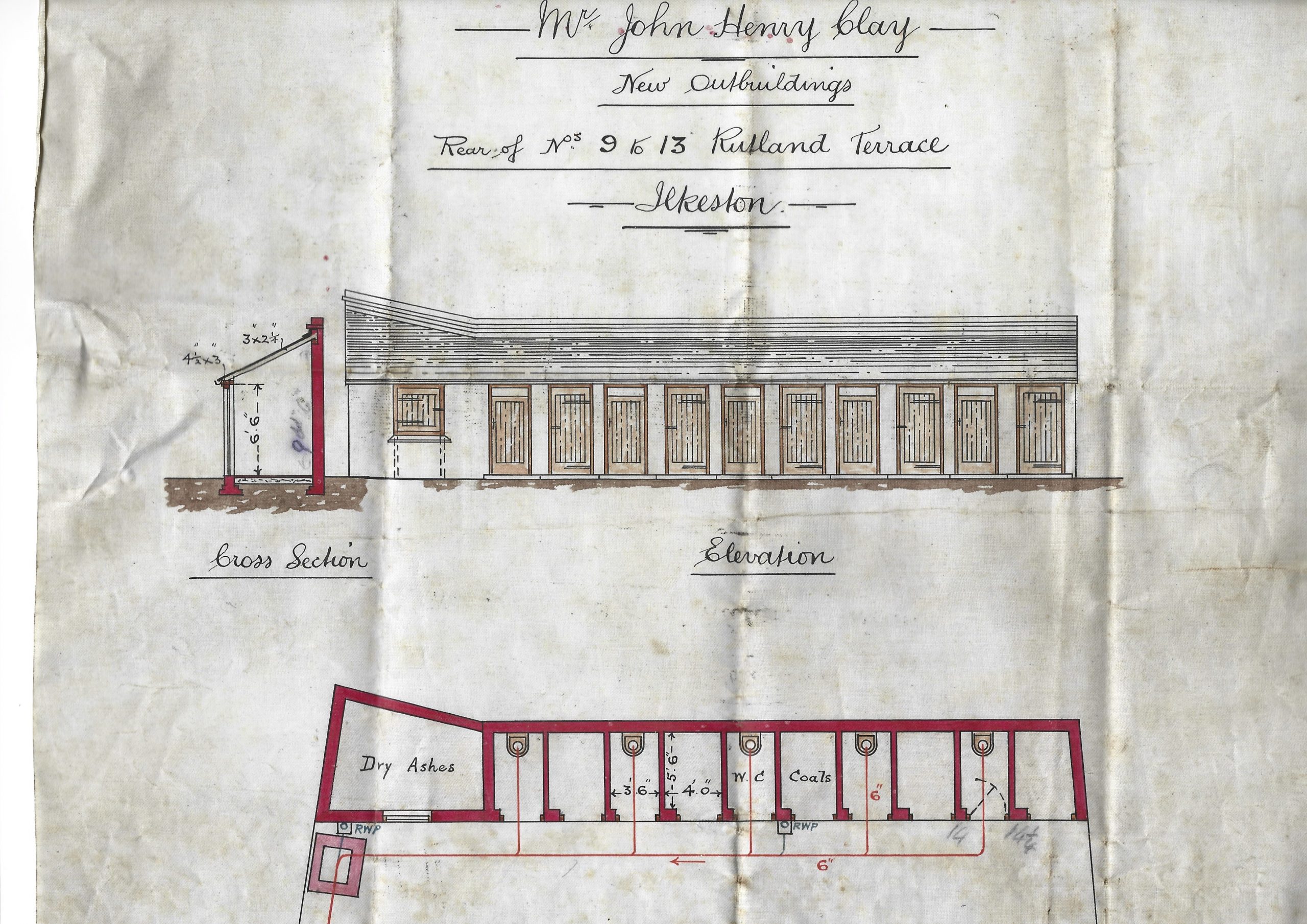

And here, below, is another, more mundane example of Charles William Hunt’s work … dated June 1915. (Jim Beardsley collection)

Rutland Terrace was a group of houses off Rutland Street, close to Ilkeston’s Gas works, while John Henry Clay was the grandson of Henry Lever Clay, landlord of the Mundy Arms. As you will see the planned ‘outbuildings‘ included a communal shed for the dry ashes and a coal-house and toilet (each with a 6 inch waste pipe) for every of the houses.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Vaccination.

The word ‘vaccination’ was first used in connection with the work of Edward Jenner at the end of the eighteenth century when he used a cowpox virus to help develop a smallpox vaccine. You can see him in the cartoon (above) showing ‘the wonderful effects’ that his treatment had on patients.

In 1853 the Government’s Vaccination Act made vaccination for all infants compulsory although it was not strictly enforced and gave rise to much resistance.

A provision of this Act was that any vaccinated child had to be examined a week later to determine the results of the vaccination.

And this is what landed coalminer Willoughby Francis Cope and his wife Emma in trouble. Their son Willoughby was vaccinated by George Blake Norman, public vaccinator, in October 1866 but the child was brought for his re-examination a week too late. The doctor felt the need to take the parents to court, as an example. There had been a public cost and inconvenience, although Dr. Norman hoped that the court would be lenient with its fine. The magistrates concurred and imposed a penalty of 6d with costs — the full penalty was 20s (forty times that which was imposed).

After this judgement it was stated that in future cases of such neglect the full penalty would be enforced — and parents were also reminded that they were liable to the same penalty if they did not have a child vaccinated within three months of its birth.

This ‘compulsion’ was extended by a further Act in 1867 and more opposition ensued.

With further Acts in 1871 and 1874 compulsory vaccination was more strictly enforced, although fierce opposition continued and anti-vaccination propaganda grew. (sound familiar ??).

One Thursday morning in June 1881 a rumour spread throughout Ilkeston that four black doctors were in town to carry out a compulsory vaccination programme on all school children in the area. Parents besieged the schools to protect their children from these unknown vaccinators and many were taken out of school as a precaution. Two or three schools – normally with more than 600 scholars – had to be closed as a result. The rumour had no foundation.

In November 1882 the Ilkeston Advertiser printed a letter from the secretary of the Derby Anti-compulsory Vaccination League detailing a recent case in Darley. A three-month old girl was vaccinated in September of that year and subsequently developed abscesses and rashes on her arms and neck; she died a month later, her parents convinced that the vaccination was the cause of her death.

After an investigation by the Local Government Board it was decided that in this case the public vaccinator was at fault in using dirty and contaminated instruments which had caused septicaemia in the infant.

The Advertiser was not convinced that this was an exception. Such cases were ‘seriously numerous, and are pretty certain to increase’.

The newspaper then outlined its case against compulsory vaccination and its simple solution…. let those who believe in the efficacy of vaccination be vaccinated — as often as they like. If their belief is correct, they are then immune to any infection… they can have no fear of ‘misguided creatures who will not admit the prophylactic poison into their bodies’.

Let those who fear vaccination more than the chances of contracting smallpox remain unvaccinated.

The latter may be ‘centres of infection’ but they cannot infect the ‘wise ones who have guaranteed themselves by Dr. Jenner’s process’.

The Vaccination Act of 1898 allowed parents to become ‘conscientious objectors’ and obtain a certificate of exemption (from vaccination) for their child, so long as it satisfied at least two magistrates. There were four magistrates present at Ilkeston Petty Sessions in April 1899 when several parents were facing ‘vaccination prosecutions’. Their defences varied — Charlotte Adams of Ebenezer Street flatly refused to have her two youngest children vaccinated (ordered to have them vaccinated immediately, and pay costs of the case); John Morley had a certificate of illness of his child, signed by Dr. Clarke (adjourned for three months until his child was well and could be vaccinated); Fred Aram had a similar defence (and a similar result); Henry Percy Mitchell had his child vaccinated the day before appearing in court (case dismissed): Phillis, the wife of George Daniels, had tried desperately and on several occasions to get an exemption certificate — she said !! (ordered to have her son Arthur vaccinated within one month, and pay costs)

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Miasma.

In the 1870’s Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch established the Germ Theory of Disease, arguing that a specific organism caused a specific disease.

Before this — and even after their work — one theory put forward was that ‘miasma’ or bad air — poisonous vapours — was a cause of disease. (Is this the theory which led to Albert Moss’s letter to the Pioneer, mentioned at the beginning ?)

To many people – and many in Ilkeston — this would seem to make sense in the newly industrialised parts of nineteenth century England with its filthy and stinking slum areas that bred disease.

The levels of disease and epidemics decreased when the sanitation and housing in these areas were improved, tending to confirm the ‘miasma’ theory.

For example in 1881 the neighbours of butcher Elizabeth Hawley of South Street were convinced that the fever, diarrhoea and other diseases in their area were caused by the stench of decaying matter coming from her premises — from the offal, blood and garbage of the slaughter-house thrown onto her manure heap. The Local Board’s medical officer Robert Wood, supported by the Inspector of Nuisances, successfully canvassed that the ‘nuisances’ should be immediately taken away in properly- constructed boxes.

In the month before Adeline Columbine was born in East Street – September 1854 – over 500 people had died in agony in the Broad Street area of Soho, London, when it was struck by an outbreak of cholera, the most deadly and swift outbreak of the disease to strike Britain.

The London weather had been hot and to many doctors the cause of the epidemic was obvious – the air was poisoned.

John Snow, a local physician, was not convinced by this explanation however, and believed that it was an infected water supply which was spreading the cholera.

Through a careful study of the disease victims and a thorough collection of data, John – the ‘father of modern epidemiology’ — was able to show a link between a possible contaminated water source and the deaths.

Though at that time the germ theory of disease was yet to be demonstrated, John’s suggested action to counter the cholera outbreak was to take the handle off the Broad Street water pump.

It seems that 26 years later a similar solution to the outbreak of fever in Ilkeston’s Springfield and Spring Grove Terraces was adopted.

And 50 years after the cholera outbreak in Broad Street, Soho, what do we find in Pimlico, Ilkeston?

“Death from English cholera at Ilkeston –the sanitary condition of the town.

Considerable anxiety was occasioned in Ilkeston on Sunday morning (July 1883) when it became known that a child named Bostock, aged about four years, had died at 8.20 a.m., in Pimlico-place, from English cholera.

“It appears that the child, who belongs to the ordinary working class, was taken suddenly ill on Friday. It became by rapid degrees very much worse, soon after it was first seized with illness, and suffered from vomiting, purging, cramp, and convulsions.

“Dr. Wood was sent for, and upon attending the child, was satisfied that it was afflicted with English cholera. He applied all the remedies within his power, but in spite of the most skilful and careful medical attention the child died. Very soon after death the body turned completely black.

“It may be explained that Pimlico-place, where the child lived, although occupying one of the most elevated positions of the town, and within a stone’s throw of the Town Hall, the headquarters of the Local Sanitary Authority, is one of the most foul spots in the place. It appears that in addition to a general state of very bad sanitary arrangements the neighbourhood of the house where the disease in question was contracted and the child died is rendered additionally obnoxious and unhealthy by people keeping pigs, Refuse, it is stated, has been allowed to accumulate until it forms a large heap, and the liquor runs down the small yard immediately facing the door of the house where this fatal case of disease has occurred. The deceased was playing about this spot during Friday before it was taken ill.

“Recently the dreadfully obnoxious exhalations of sewer-gas from the gratings in the Market-place, at the corner of the thoroughfare known as Pimlico, and in Bath-street have formed a fruitful topic of comment, and some letters have been addressed to the local newspapers on the subject, but at present there is no change.

“The smells continue, and it is stated that there is some cause to fear, although precautions have been taken to prevent any further result from the deplorable case that has already occurred, that unless some decided steps are taken by the proper authorities to speedily prevent the constant uprising of the noxious gas that is now daily encountered in the town, something more alarming than a solitary death through bad sanitary arrangements will take place”. (IA July 1883)

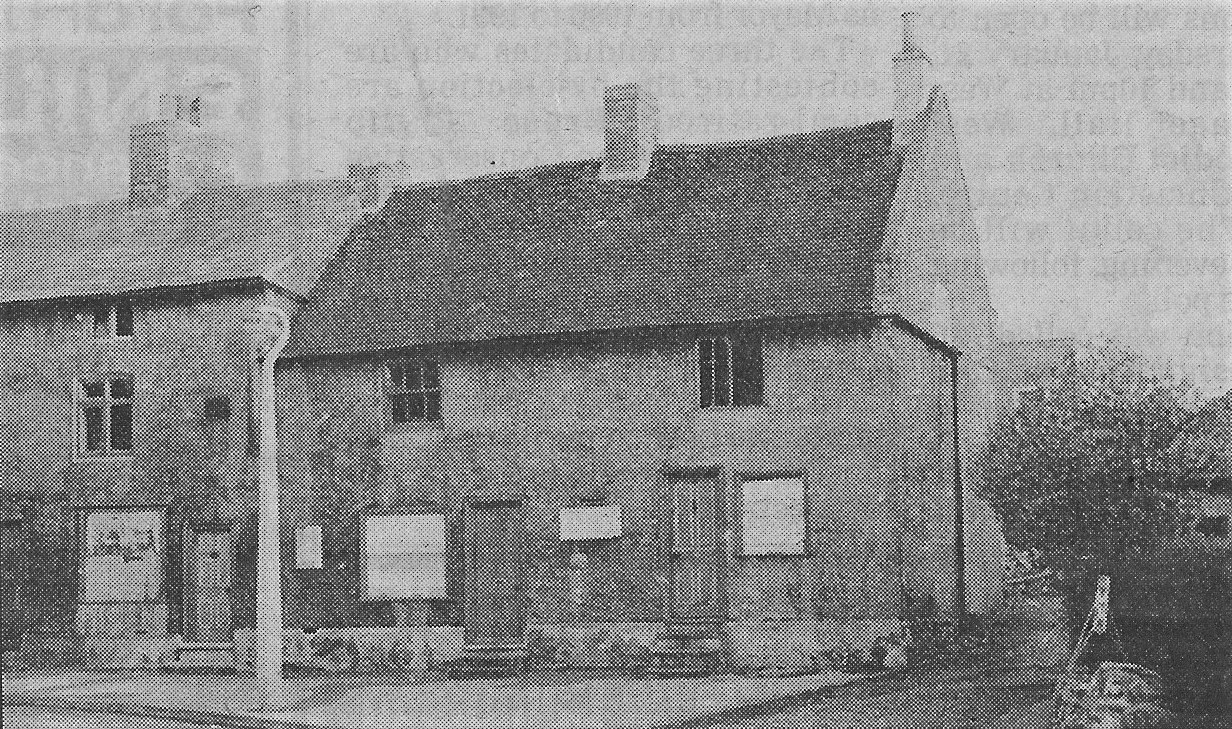

Cottage in Pimlico (late 1950’s – early 1960’s) part of the ‘complex’ making up Pimlico Place. The Sir John Warren back yard is on the left. The premises have been demolished to make way for a Council carpark.

*Pimlico Place was a cluster of cottages off the south side of Pimlico and located behind the rear yard of the Sir John Warren Inn which itself was contributing to the unhealthy environment.

Members of the Local Board were satisfied that ‘offensive accumulations from a pigstye’ had led to this case of cholera. The surveyor was sent to examine the premises of the deceased and ‘a more efficient system of disinfecting the public sewer grates was decided upon’.

The Board ordered Isaac Attenborough, owner of the Inn, to improve its sanitation. More and better privies were needed as well as improved drains and cesspools.

But six months later Isaac was at the Petty Sessions, summoned by the Board for allowing a nuisance to exist on his premises. The inn’s urinals and drainage were still in need of improvement. Isaac was not best pleased; over the last few years he had made several alterations to satisfy the Board’s surveyor — they could not always be expecting him to be altering everything, could they?

Oh yes they could !!

And “considerable anxiety was occasioned in Ilkeston” yet again, just over 10 years later when a supected case of cholera was declared after the death of Benjamin Lay of Morris Row in Cotmanhay. He had been employed as a night-soil collector and became ill in early September 1893, dying of ‘choleraic diarrhœa’ very shortly after. Joseph Carroll, the Council Medical Officer of Health, informed the Local Government Board immediately.

A week later and another death. Annie Adkin (nee Frost), the 20-year-old wife of coalminer John Henry Adkin, living at 51 North Street, died on September 19th after a bout of severe ‘choleraic diarrhœa’, lasting 18 hours. She had recently visited her parent’s home in Nottingham Road where her brother Robert was dying of typhoid fever. Within 24 hours of returning to her own home she was dead. Once more Joseph Carroll was called, this time accompanied by Sidney Barwise, medical officer of health to the Derbyshire County Council. The former’s view was that the death was caused by true Asiatic cholera though no definitive decision could be made until Annie had been examined by Dr. Klein of the Local Government Board in London (Her intestines were forwarded to him for examination). Once more suspicion fell on Ilkeston’s water supply, ‘not the best for purity’ !!

This was followed by a visit from an Inspector of the Local Government Board who recommended that all the relevant premises in Morris Row, North Street, and Kensington be thoroughly cleansed and disinfected. Also all privies and ashpits were to be emptied, free of charge, the contents burned and the privies etc. be disinfected with Bi-chloride of Mercury (which of course could lead to acute kidney failure, stomach ulcers, intestinal damage, and death if acute exposure to it occured !!). Extra men were hired to increase the removal of night soil and local doctors were warned to keep an eye out for cases of acute diarrhœa. When the Inspector called a month later he was pleased with the way the Council had responded and the measures it had put in place. Relief !!

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

1887: Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee legacy ?

In the later 1880s and after the damning medical and public health assessments of Ilkeston (above), several of those in a position to influence town events were cognisant of the the town’s deficiencies. Consequently, as the time to celebrate the Queen’s Jubilee approached, ideas were floated and discussed by both the old Local Board and the new Town Council. Public baths (proposed by Walter Tatham), recreation grounds, free libraries and a cottage hospital were included in the list but all discarded. The latter idea received warm support but, when examined, was thought to entail far too much expense to build (at least £1500) and then to maintain (about £400-£500 per year).

So, a fund of £100 was allocated to subsidise the Sunday Schools’ provision of children’s treats on the day, to help Odd-fellows’ lodges organise amusement for the adult population at the Recreation Ground, and to provide something like roast beef and plum pudding for the aged poor. And later, opening hours for all the town’s inns and beerhouses were extended until 12 midnight.

Under beautiful weather, Ilkeston’s Jubilee Day of June 21st included a telegram to the Queen, much street decorating, divine service in the parish Church of St. Mary’s and then hymn-singing in the Market Place, a photograph taken from the Town Hall, teas for all school-children in their own schools followed by evening out-of-doors amusements. Adults meanwhile were treated with a free fete and gala on the Recreation Ground, while they could listen to the Ilkeston and Cossall Brass Bands. An in the evening the Town Hall was brilliantly illuminated. And then a large number of sheep were sacrificed, roasted and their meat distributed around the thronging populace.

The Old People’s dinner treat was held on June 22nd, in both the South Street schoolrooms and in the new part of the Mayor’s factory in Market Street, to accommodate the 600 recipients.

The total cost of £196 1s 1d, twice what was originally estimated, was covered by the public subscription which amounted to £206 6s 6d. The £11 4s 8d which was left over was paid into the Cottage Hospital Account.

And a Wonderful day was had by all !! (except the chosen sheep)

——————————————————————————————————————–

Disease in the town at the end of the century

A] In November 1896 Priscilla Fensome was a 15-year-old lass who lived in Belvoir Street and worked in a factory at Ilkeston Junction. One Monday evening at quarter past seven she returned from work complaining of feeling ill. Over the next few days she remained at home while her condition deteriorated, There were several visits from the doctor inbetween her bouts of vomitting, choking and semi-consciousness. By Thursday morning Priscilla could hardly get her breath and now lapsed into total unconsciousness; she died at half past eight that morning.

The inquest into the girl’s death, held at the Mundy Arms, revealed that some progress had been made in Ilkeston into understanding infectious disease, its causes and its prevention. The state of the drains to the house were discussed and the location of the tub closet relative to her house. James George Willis was now Medical Officer of Health for Ilkeston Corporation and he had visited Priscilla the day before her death. In his testimony he mentioned his suspicion of typhoid being the cause of her symptoms, had ordered her to bed — she had previously been lying on a sofa downstairs– and had suggested the liberal use of carbolic soap around the patient’s bed chamber. After her death the autopsy and the symptoms he had witnessed revealed to the doctor a very virulent attack of the fever. That in his opinion was the cause of death. The jury returned a verdict of “death from natural causes, viz., typhoid fever”.

B] In May 1899 the Town Council was struggling to combat an outbreak of typhoid fever and called a special meeting to discuss what measures needed to be taken. Edwin Trueman wanted regular bacteriological testing of all the town’s water supply. Frederick Chambers offered a less wide-ranging system, suggesting the Town’s three water sources, Stanley Brook, the Nutbrook, and the pumping well, be tested. Dr. James George Willis, the Council’s Medical Officer of Health, confirmed that the Stanley Brook water had long been a source of concern to him, and after he had spoken the Council erred on the side of caution and adopted Edwin’s resolution.

A deputation had just returned from inspecting a system of high pressure water filtration near Leeds and had been most impressed. Hence the Council then ordered that a similar Reeves patent filter be ordered for Ilkeston. Further measure were suggested and adopted — ventilating grates to the sewers in the middle of the roads at the centre of town were to be removed and the opening sealed, while ventilating shafts at the side of selected buildings and reaching up to their top, were to be built. To encourage isolation, Charles Mitchell wanted all admissions to the sanatorium to be free, and on the simple order of a qualified doctor; Town Clerk Wright Lissett pointed out that this would be illegal and so that idea was quietly dropped !!

C] In February 1900 typhoid struck the town again. There was a strong feeling that the town’s water supply was responsible and so the Council had it “bacteriologically examined“. The conclusion was that “no typhoid was discovered“. However as a precaution offered by Alderman Charles Maltby, chairman of the Health Committee, Ilkeston residents were encouraged to boil the polluted water !! … the bacilli of typhoid would not stand 212ºF. This encouragement was circulated around town via a handbill. Worried townspeople subsequently met at the Town Hall where a resolution was adopted:- “That this meeting of ratepayers and inhabitants of the borough of Ilkeston, being dissatisfied with the present water supply, which has been condemned by an inspector from the Local Government Board and the medical officer of health, urges upon the Town Council the necessity of obtaining a sufficient supply of pure water, and also urge that the opinion of a leading professional expert should be immediately obtained, dealing with the whole question of the water supply“.

The Council responded almost immediately and called in George Hodson of Loughborough, a civil engineer of some repute, to advise on the supply of the town’s water.

1899-1901: The St. John Ambulance Association in Ilkeston

On January 18th, 1899 a well-attended public meeting at the Town Hall was held, to promote an ambulance corps and nursing division for the district. As well as dignitaries from Ilkeston, Shipley, Stanley, Stanton, Mapperley and Cossall, the meeting was visited by a section of ambulance men in uniform along with four nurses from the Tibshelf Corps who together gave a display of stretcher and bandaging work.

Ambulance work at the turn of the century (BBC Archive)

The Chairman Edward Miller Mundy explained the movement’s advantages, stating that less than 3% of the 2081 men working at his collieries were certified to render first aid. He wanted to raise £150 to meet initial expenses and he would start the ball rolling with a donation of 20 guineas (much applause). Further donations of over 30 guineas were then promised. Of course, a committee had to be established.

On December 14th 1900, at the Rutland Arms, the town welcomed home returning ambulance and other volunteers from the war in South Africa. They were Messrs. S Beniston, J Beardsley, S Burgoyne, S Rowland, C Rowland, T Sinfield, J W Read, and Corporal G Syson of the South Notts. Yeomanry.

——————————————————————————————————————–

And now Adeline takes us on, to meet the Sudburys