Before we go any further, let me give you a list of all the Mayors in Victorian Ilkeston. ….

1887 (part of) Francis Sudbury

1887-1888 Francis Sudbury

1888-1889 William Wade

1889-1890 William Tatham

1890-1891 William Tatham

1891-1892 John Moss

1892-1893 William Merry

1893-1894 Francis Sudbury

1894-1895 Frederick Beardsley

1895-1896 Charles Maltby

1896-1897 Samuel Richards

1897-1898 Samuel Richards

1898-1899 Samuel Robinson

1899-1900 Charles Mitchell

1900-1901 Richard Hunt

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1887 – 1888

Francis gets a second term 1887-1888

On November 9th, 1887, at the first meeting of the new Town Council, Francis Sudbury was elected as Mayor once more, but this time to serve for a full year. He was the only Gladstonian Liberal mayor in Derbyshire at that time, and the Conservative Derby Mercury (never a fan of Liberals) conceded that he fully deserved his re-election.

It was also resolved to hold quarterly meetings on the first Tuesday in February, May, August and November.

And why not appoint a Town Crier, complete with hat and coat ? — James Henshaw was later chosen out of the nine applicants.

Selecting the membership of the various Council committees however was far from an easy task, with claim and counter-claim, dissent and a few insults thrown in, and complaints (many, but not all, coming from Charles Mitchell — though now he had more allies to argue along side him).

Troublesome Councillors

It was the North Ward which housed the majority of the “troublemakers”. Both the newly elected Councillors there, Enoch Limb and Isaiah Fisher, were chosen to serve on Committees which were not to their liking and which they thought were of the least importance. So, along with Samuel Bloor, Charles Mitchell and William Manners, they vehemently expressed their displeasure. They later called their own meeting at the Wesley Street School in Cotmanhay to address their ‘constituents’ and there was strong support from all attendees for the actions of their representatives. There was also condemnation of the ‘up-town’ party and their councillors — perhaps reminiscent of 1864 when the Local Board was first formed amid similar conflict between the ‘up-towners’ (the posh folk who lived in the centre of town) and the ‘down-towners’ (the Cotmanhayites).

————————————————————————————————————————————————

Public Baths for the town ?

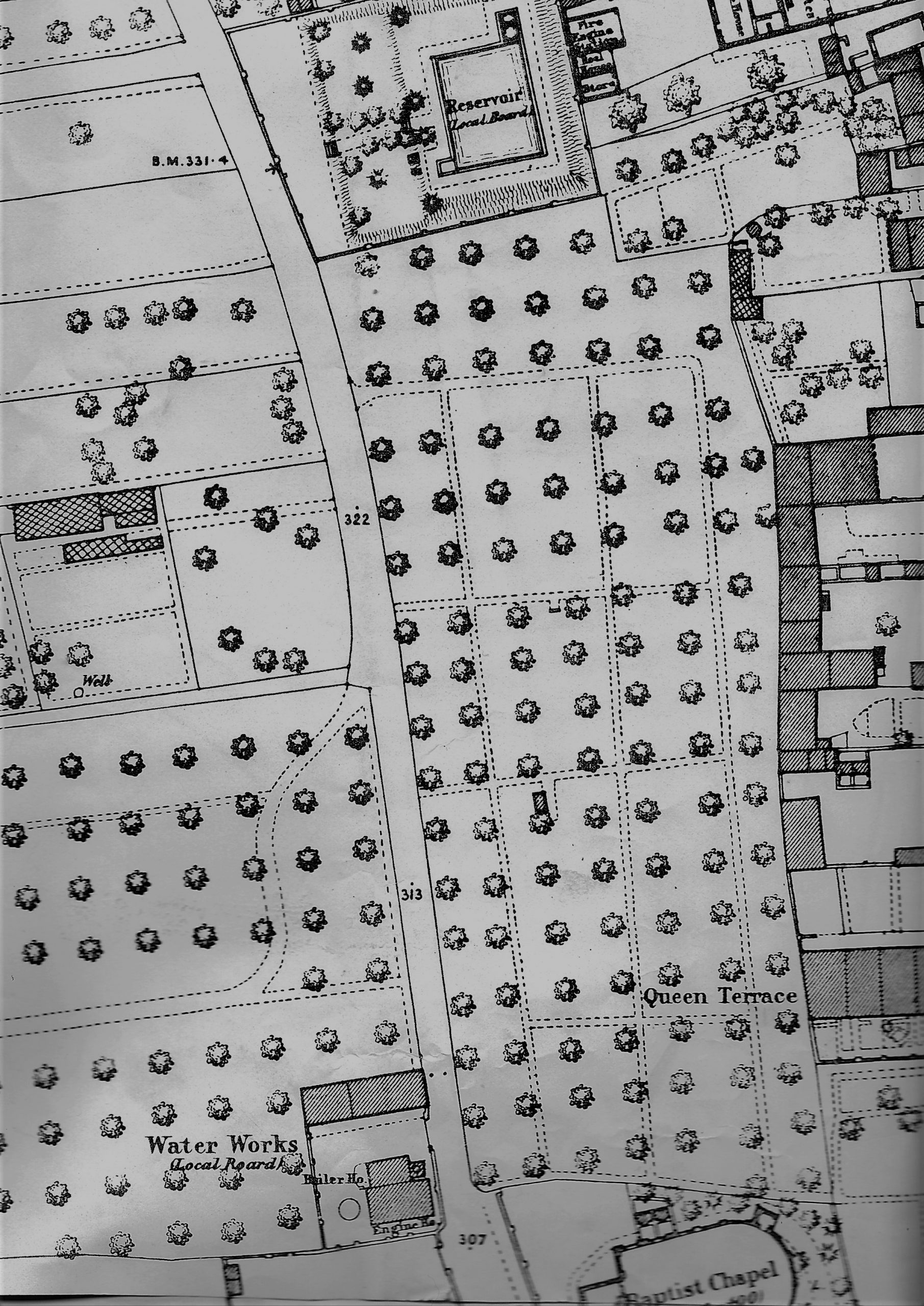

By June 1887 the Council had decided to sell off the Water Works Pumping Station at the bottom of Queen Street, with its “engine, boiler, pumps, engine house, dwelling house and surrounding land of 900 yards“. It suggested that the property would be ideal as a brewery or an aerated water manufactory; the pump, fixed in a shaft, was able to extract 1500 gallons and upwards of water per day.

But then, also in that month, Charles Mitchell raised an idea originally put forward by Samuel Beardsley, for erecting public baths on the site; it was supported by Walter Tatham and George Haslam. A committee was formed and the whole area of the old Waterworks was carefully examined as a possible site. More land around the waterworks would be needed and this was owned by the Duke of Rutland and the Trustees of the Cossall Hospital. The Duke gave his permission to use his piece of land but the ‘red-tapeism’ of the Cossall trustees was holding up the process.

On the map (right) the Water Works stood on the site of the Flamsteed Centre in Albert Street’

The reservoir (at the top) stood behind the Town Hall and, as you might see, was close to the Fire Engine Station, with a Coal House and Store to its right. Also there, just off the map, was a Hose House.

Below … and we are looking down Albert Street from Wharncliffe Road.

A is part of the Congregational Church. B is the Derbyshire Army Cadet Force Centre, hidden behind which is the Flamsteed Centre, site of the old Waterworks. C is the corner of Queen Street where the new Baptist Church stands

A very short time later, a public meeting was held in the Market Place (I presume at the Market Hall) at which Councillor Joseph Scattergood presided. He pointed out both the physical and social benefits of public swimming baths, while the danger and nuisance of canal-bathing, especially by juveniles, could be avoided. He explained the progress (or lack of it) made by the Council but was very confident that every obstacle could be overcome. Others then spoke about possible sites (in Bath Street or behind the Church Institute), and who should get the credit for thinking of the idea in the first place !! (loudly claimed by Walter Tatham). Finally a resolution was passed:– “that this meeting is of the opinion that public baths should be erected in Ilkeston in as convenient a position as possible”.

However, as the Mayor at the time pointed out, “these sort of things take time” … and how accurate he was.

The issue did raise its head again, in 1895 when Edwin Trueman suggested that the Borough Surveyor should be instructed to draw up plans and estimates for a Public Baths at the rear of the Town Hall, possibly utilising the disused water tank there, and the land around it. It would be economical and convenient, and even if only temporary, would serve the town for maybe 20 or 30 years. The suggestion was adopted, and the Council would wait for the report before pursuing the idea — or not !!

And again in 1899 it was further discussed.

The town had to wait until August 31st 1921 before the swimming baths (just up the road from Albert Street) in Wharncliffe Road were opened — on the site of the Town Hall reservoir would you believe.

The Town Hall about 1980, viewed from Wharncliffe Road with a new extension buildings at the rear. (C. I. Parry of EBC)

The site of the reservoir, mentioned above, which later was the site of the new simming baths, was at the end of the extension, behind the trees on the left.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

And on into the year 1888

1888 marked the tricentenary of the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the bicentenary of the Glorious Revolution, the centenary of the Regency Crisis, and was the year in which the people of Ilkeston could inspect their first two Mayors … though not simultaneously.

Who owns the Market Place ?

As early as July 1887, the newly-formed Town Council had discussed the Market Place issue.

Some councillors were keen on reviving the Thursday market held there, and the idea of purchasing the area from the Duke of Rutland therefore surfaced. However the price which he demanded was far too high for the Councillors, and so their negotiations turned towards renting the Market Place.

At the end of February 1888, the Duke of Rutland offered the use of the Market Place for an anual rental fee of £100; the Market Hall, which stood there (it used to be the Girls’ Church School) was now the home of John Fish, the Market Superintendent, and the Duke asked that he should be allowed to continue to live there, rent-free, for the remainder of his life, and be granted a compensation of £150.

And just in time !! … the Duke died a few days later, on March 4th.

Thus, on March 26th, 1888, the Council became the tenants of the Market Place and its rights. (It wasn’t until 1920 that it managed to purchase outright the area).

When the October Statutes of 1888 arrived in Ilkeston, it was the first time that the Market Place was in the hands of the Corporation. Market Street was shut off for three days and shows were allowed to set up there….. “and there were plenty of shows — some of questionable character, roundabouts, etc., and judging by the throng and din on Thursday night they must have reaped a good harvest”. (Long Eaton Advertiser Oct 27th)

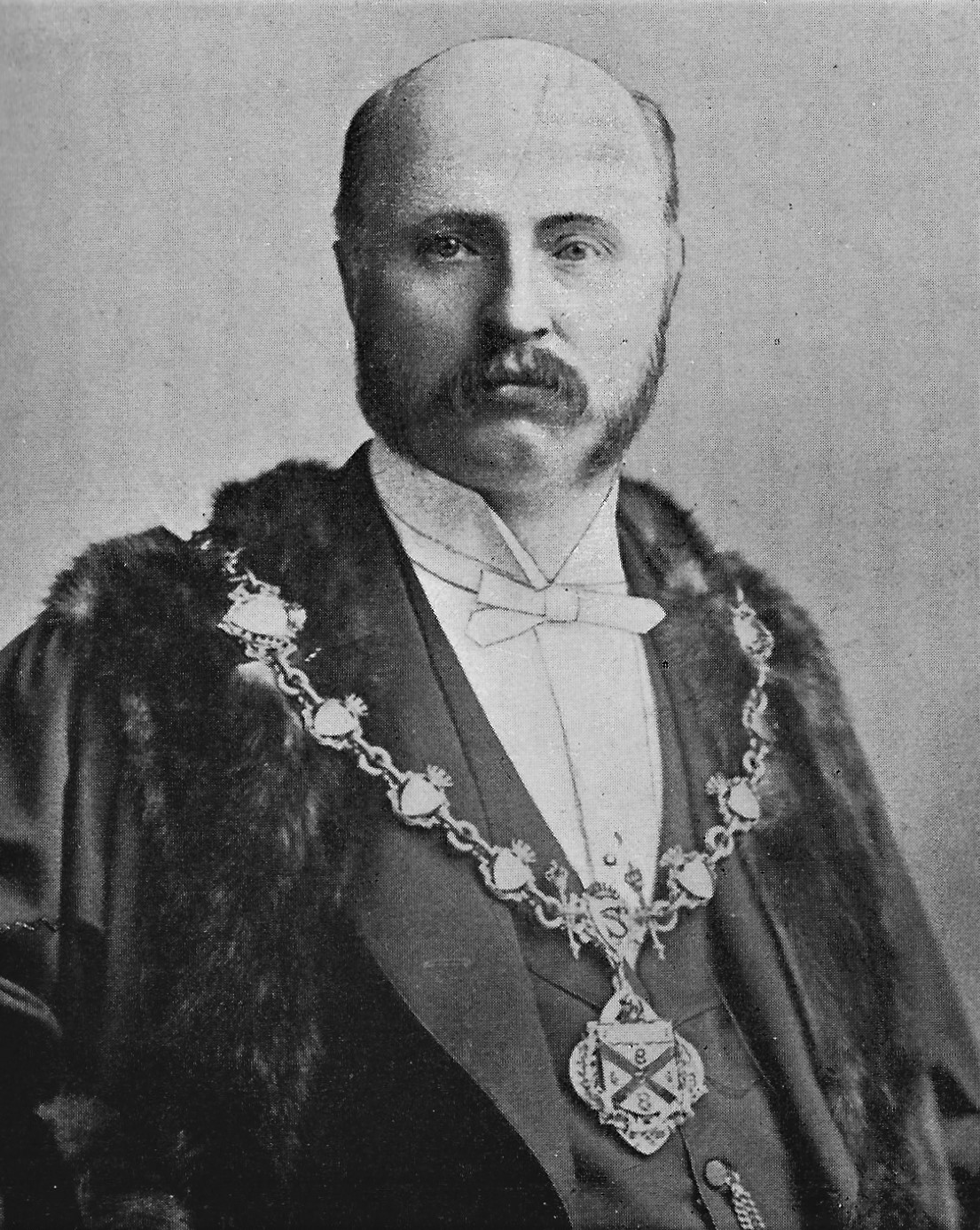

Portraits

The Derbyshire Courier (Dec 8th 1888) reported that — A movement is on foot at Ilkeston to present the Town Council with a portrait in oils, from the brush of Mr. Redgate, of Nottingham, of the first Mayor of Derbyshire’s newest borough, Mr. Alderman Francis Sudbury, J.P., to wit. This gentleman was one of those who worked the hardest in getting the town incorporated, and the compliment it is proposed to pay him is as graceful as it is well-deserved.

A committee was formed — (as always ?!!) — to collect subscriptions to pay for the portrait which was destined to hang on a wall of the Town Hall.

The result you can see left.

In March 1889, at a complimentary dinner attended by all of the town’s ‘great and good’, the finished portrait, by Nottingham artist Sylvanus Redgate, was presented to the municipality.

It was accepted by the second Mayor of Ilkeston, William Wade, on behalf of the people of the town.

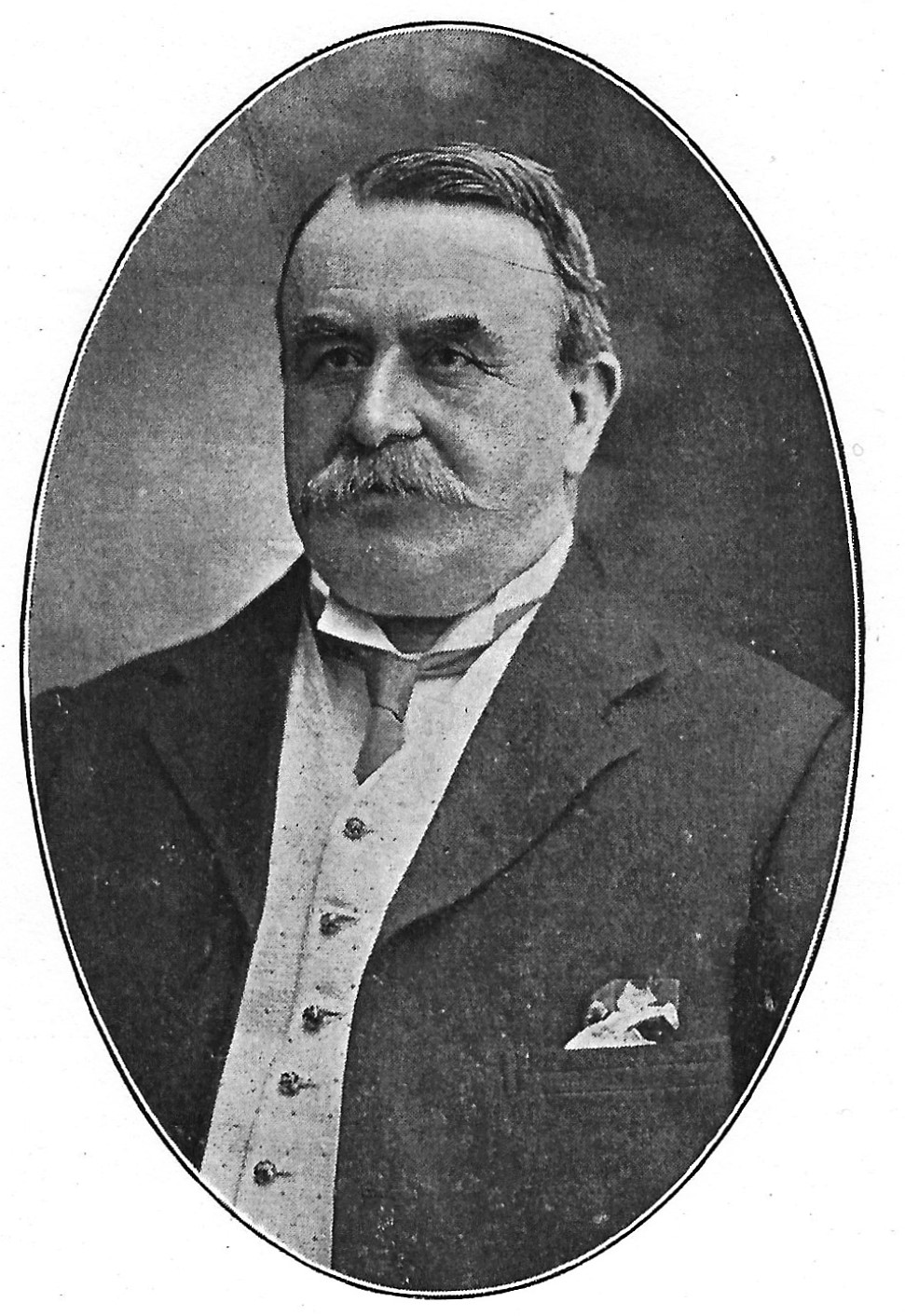

On Friday, November 2nd 1888, in a private meeting of the Town Council, William Wade was nominated to succeed Francis Sudbury as Mayor of Ilkeston — and a further portrait now had to be commissioned.

Alderman William Wade, second mayor of Ilkeston (1888-1889) by Sylvanus Redgate (held by Erewash Borough Council)

An article in the Derby Mercury (Nov 28th 1894) described the desire of some of the Council members to show off their plumage … “The Mayor and Aldermen are gorgeously attired, and wear their robes regularly at the monthly meetings. The Mayor has a scarlet robe, profusely trimmed with sable fur; he also wears a gold chain and a cocked hat, whilest the Aldermen are attired in robes of a rich mazarin blue, trimmed with sable. The Town Clerk, too, has a handsome gown of black silk, beautifully trimmed, and also wears a cocked hat. The common Councillors, unlike their brethren in some of the old towns in the West of England, do not wear any distinctive garb”.

Street Improvements.

In October 1888 the Council put forward plans to improve some existing streets; several of the pavements were made of bricks which, over time, had become very uneven. Parts of Cotmanhay Road and Granby Street, Bath Street, South Street, Market Street and Nottingham Road were all listed for a ‘make-over’ with Victoria stone, new gutters and gullies.

Secondly the Council wished to better connect Hallam Fields to the centre of town, via Nottingham Road; this would involve building a new road from that outlying district to the bottom of Nottingham Road, at Gallows Inn. It would be curbed and channelled, fenced in by iron railings on both sides, and would be lit when the gas mains had been laid. The scheme had been supported by the owners of Stanton Ironworks and by the residents of Hallam Fields and Nottingham Road.

The Council wished for permission to borrow £4000 to finance the work and so had to apply to the Local Government Board.

This was the birth of Corporation Street.

Seven years later and Hallam Fields, the Stanton Ironworks Company, gas pipes and the Town Council were once more a topic of conversation. By June 1895 the Stanton Company had made an offer to supply gas to every house in Hallam Fields and to pay for the consumption with a lump sum …. so long as the Town Council laid the gas mains in the streets. The Gas Committee of the Council had rejected this offer and Wright Lissett, the Clerk, had to explain why this seemingly generous offer had been refused, to the rest of the Council. His reason was that the Gas Committee did not lay gas pipes in streets which were not public or had any reasonable possibility that they would become public. For example, if a pipe needed mending in a private road, the Council would need permission before it could access the problem. Edwin Trueman pointed out that about 150 houses were affected — surely the Council could lay mains in the streets ?!? The Clerk replied that they would gladly do this in public roads and then supply a large gasometer to the Stanton Company for their houses.

See how the story of Hallam Fields’ gas supply develops … here

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Not more elections ?!

On November 1st 1888 the annual polling took place for the Council seats of the six ‘retiring’ councillors — two in each of the three wards — and by 9am of the following day the results were known.

In the Central Ward, Samuel Robinson (Liberal) and Edwin Sutton (Independent) both retained their seats, the latter only just !!

In the North Ward, Samuel Bloor (Independent) kept his seat, although Frederick Beardsley lost his to Henry (?) Tomlinson (both Independent).

In the South Ward, Edwin Trueman (Independent) and John Moss (Liberal) were both elected as ‘new’ members of the Council; the one retiring member trying to retain his seat was Joseph Scattergood (Liberal) who was defeated by a clear margin.

Some of those standing for election chose to display clearly their political affiliation, while the Independents standing were those who decided to keep ‘party politics’ out of the contest. For example Edwin Trueman was a recognised and staunch Conservative but campaigned on the platform that he would serve as ‘a citizen of the borough’ and not of a political party. He headed the poll in his district — and after his victory was declared at the Town Hall, he was carried on the shoulders of his cheering supporters into the neighbouring Sir John Warren for a celebratory pint … or three.

The Local Government Act 1888

This Act of Parliament established county councils and county borough councils in England and Wales. It came into effect on 1 April 1889, though the first of the triennial elections for the new County Councillors took place in January 1889.

In Derbyshire, of the 60 elected members, 32 were ‘old and tried‘ magistrates, gentlemen of ‘capacity, energy and independent character’.

In Ilkeston, North Division, John Bamford Slack, a Gladstonian Liberal and solicitor of Netherlea in Pimlico Lane, defeated Councillor Edwin Sutton, auctioneer, standing as an Independent. In the South Division, Alderman William Tatham easily defeated Councillor Charles Mitchell, grocer of Hallam Fields.

By the time of the next election, in 1892, John Bamford Slack had long left the area, taking up a post in London (though he still was an active member of the county council). He did not stand in 1892 — the contest in Ilkeston’s North Division being between Conservative Edwin Trueman, who probably knew he stood no chance of success and so encouraged the electorate ‘to choose the best man for the job and keep politics out of the election’ and Gladstonian Liberal Dr John J Tobin, who was returned handsomely.

———————————————————————–

Under the heading of A Local Notable Wesleyan Methodist, the Long Eaton Advertiser published a short profile of John Bamford Slack, taken from another publication (August 12th, 1893).

He was born on July 11th 1857 at Green Hill House, Ripley, where he lived until he was married on March 15th, 1888 to Alice Maude Bretherton. His father was a Wesleyan Methodist and became a local preacher in 1826. John entered Wesley College, Sheffield in April 1868 and left in October 1876, when he was head of the school (and captain of the cricket eleven). Aged 16 he had matriculated at London University in 1874 and two years later took his B.A.degree there. In March 1877 he was articled to an eminent Derby solicitor, Samuel Leech, and was admitted a solicitor in 1880, having passed his final examination with honours.

In October 1880 John purchased a solicitor’s practice in Ilkeston and was there until December 1889. As we have seen (above) he was elected a member for the Northern Division of the Borough of Ilkeston, of the first Derbyshire County Council. In January 1890 he left for London and the firm of Messrs. Monro, Slack & Co. He had been a local preacher since 1877 and maintained his Wesleyan connections and duties on his arrival in London.

“We may add that Mr. Slack has been a life-long total abstainer”

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

The town’s pubs (Part 1)

On numerous occasions throughout this year, the Council’s attention and deliberations were drawn towards the town’s Public Houses and liquor trade. I have listed a few here.

The Durham Ox … John Trueman, who operated the brewery in Durham Street called the Durham Ox Brewery, with James O’Hara, paid his Council bill for the making up of Durham Street.

The Anchor Inn (owned by the Crompton Brewery Co.) and the Bull’s Head (owned by William Small) were both found to be without a proper supply of water. The problem with the latter would be solved when it was agreed that a water main should be laid from the Bull’s Head to the new isolation hospital (the Sanatorium), a short distance away on Little Hallam Lane.

The Queen’s Head … the Council had ordered landlord John Trueman (again !!) to install two water closets at the pub. However John had provided an ash pit and two privies instead. After some discussion, it was decided to accept John’s alterations.

The Old Harrow Inn … William Small (again !!) also traded as a butcher and had a shop under the Inn, at 1A Bath Street. The Council resolved to lay on a gas supply for William. And just a short time later, the landlord William Holmes was to be taken to court for non-payment of his gas bill !! (It is unclear whether the two resolutions were related).

The Trumpet Inn … Situated on Cotmanhay Road, it was owned by Messrs Shipstones & Sons and tenanted by James Bromhead. It came under close scutiny by the Medical Officer of Health who discovered that it was in such a filthy and unwholesome condition, as to be a serious danger to anyone within its walls !! He suggested therefore that the walls should be whitewashed and the whole premises be thoroughly cleaned, before it recommenced trading. The Council adopted his suggestion.

The Sir John Warren … the Council agreed to erect a drinking fountain opposite the Inn (below)

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

1888 – 1889

The Town’s pubs (Part 2)

Throughout this year the Council continued to scrutinise drinking establishments.

The New Inn … The Inn’s water bill hadn’t been paid !! And so, either the owner (James Bonsall) or the tenant (William Trueman), or both, would be taken to court.

The White Lion … The part of Nottingham Road from South Street to the White Lion Inn was to be renamed as White Lion Square.

The Royal Oak Inn … The Inn’s landlord William Booth was fed up with the Salvation Army members and their band gathering opposite the Royal Oak on Primrose Hill. Their playing and singing were created such an annoyance that he was driven to write a complaining letter to the Council. I don’t think that this was the same William Booth who helped establish the Salvation Army !!!

The Needlemaker’s Arms … Wright Lissett, the Town Clerk, was directed by the Council to investigate a charge made by Annie Limb of 58 Wesley Street against Joseph Tatham of the Needlemaker’s Arms (Was he the son of the landlord Herbert ?). It was claimed that on January 15th, 1889, at just after 10pm in the Market Place, Joseph felt the need to urinate on Annie’s dress.

The New Inn … It was resolved that “if the material and rubbish on the footpath against the Inn” was not cleared away pretty sharpish, legal procedings would be taken against the contractors, Messrs Keeling and Shaw.

The Rutland Hotel … Bath Street was widened in front of the hotel

And also, at the end of this period, a memorial was sent to the Lincensing Committee, asking for the licensing of premises to take place at Ilkeston rather than at Heanor, as had been the case until now. These were what were referred to as the ‘Brewster Sessions‘.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Votes for Women !

At the monthly meeting of the Town Council in April 1889, it was decided that the Mayor, on behalf of the Council, should sign a petition to Parliament in favour of extending the franchise to women.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

A new water fountain 1889

In the spring of 1889 the Council financed an iron fountain “of handsome design” in the open space in front of the Sir John Warren hotel.

The base was of Aberdeen granite while the iron work was suppied by Andrew Handyside & Co of the Britannia Iron Works in Derby.

It was approximately 18 feet tall and surmounted by three lamps, with a basin for the use of the people and a trough for horses and cattle.

On Saturday afternoon, April 20th 1889, in a very formal ceremony, the fountain was switched on for the first time, by Alderman Francis Sudbury. No speeches were made.

Right: the fountain at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library)

And it was nearly a very short-lived life for the fountain !!

About two o’clock in the afternoon of January 27th 1890, Arthur Tinsley, the proprietor of the Sir John Warren hotel, went down into his cellar and struck a match to light the gas jets; the result was a loud explosion. Outside, in the Market Place, some men were blown off their feet; part of the paving outside the hotel, close to the fountain, was damaged; its lamps were shattered; its base stonework shifted several inches; and for a time smoke could be seen coming from a crack close to the fountain’s gas tap. Since the beginning of the year people had detected a smell of gas in this area and this explosion appears to have been the result of a build-up of gas in a reservoir under the fountain.

The Borough Surveyor, Henry James Kilford, was soon on the spot, along with his workmen, who set about dismantling part of the fountain. The definitive cause of the accident was never really established but it was thought that lighting the gas jets in the cellar had perhaps ‘communicated‘ with the escaped gas in a hole going from that cellar, underneath the Market Place and known locally as ‘John o’Gaunt’s Hole’ (and said to pass under the Church and into fields several miles away !!) That fire might then have ignited gas under the fountain and caused the explosion. A lot of ‘mights’ and ‘perhapses’, but no-one was seriously injured and the fountain sustained only temporary damage.

And a new water supply ?

As we have seen above, by June 1887 the Town Council had decided to sell off the Pumping Station at the bottom of Queen Street

In August 1889 the issue of Ilkeston’s water supply once more reared its head. At this time the town’s residents got their water from either the artificial lake at Little Hallam (‘the Beauty Spot’) or from a disused colliery at Kirk Hallam which had been brought into use at a time of difficulty and shortage, or from the pumping station, erected in 1878, near the Peacock Colliery in Heanor Road.

The Beauty Spot at Little Hallam in later life … no longer a water reservoir

Then the Borough Surveyor, Henry Kilford, produced drafts to show that his new plans, based at the Kirk Hallam Pumping Station which, if fitted with new engines, would use less coal, would need to be working fewer hours, with fewer workers, to supply more inhabitants, assuming larger mains would be laid. A sum of £7500 would need to be borrowed to finance these improvements … a loan which the Local Government Board would have to agree to.

The loan was soon sanctioned by the Government and the town could then move to a system of water supply based around one source — at Kirk Hallam. Not slow to spend the borrowed money, a large pumping engine was bought for Kirk Hallam by the Council, and, as ‘back-up’, a new engine house was proposed for Little Hallam. By this time the pumping station at the end of Queen Street was no longer supplying water, while the one at Shipey had also been discontinued — the neighbouring Peacock Colliery had been taking away the water and in the process, contaminating it.

But by February 1891 the water supply to the town was still a very contentious issue, attracting many critics, including several members of the Town Council !!

A public meeting of ratepayers at the Town Hall was convened at the end of that month, to consider what needed to be done to improve Ilkeston’s water, and what action should be taken by the Council. The meeting chairman — the Unitarian minister, Leopold G. Harris Crooke — who had had the water analysed by experts, had before him several bottles of the liquid, ranging in colour from fairly clear to downright filthy. All the samples had been collected from streams which ran into the Little Hallam Reservoir, and from which it was supplied to the town as ‘drinking water’, despite the fact that it was contaminated with sewage.

The Rev. Crooke damned the Corporation. It was legally obliged to provide pure and wholesome water, and in sufficient supply. In neither point did it meet the requirements, he argued. The ratepayers needed to take action !!

What to do ? Why, pass a Resolution, of course !! At least it would alert the Council to the strength of feeling felt within the town, especially as it was supported by Dr. Robert Wood, the vicar of St, Mary’s, and Councillors Scattergood, Mitchell, Trueman and Samuel Wood. If the Council simply ignored their concerns, a complaint would be made to the Local Government Board … and then an Inspector would call !! There would be some startling revelations.

The following Town Council meeting, at the beginning of March, was devoted to the ‘Water Issue‘ discussion and was led by Edwin Trueman. He argued that, because of the rapid growth in the town’s population, Ilkeston had had been forced to develop a system of multi-source water supply, both expensive and unsatisfactory. The Council had been moving towards relying upon the Kirk Hallam source as its main supply, but Edwin argued that this source would never give sufficient supply for the town — he calculated a 100,000 gallons per day deficiency — and nor was the quality adequate, as proved by the analysis of experts.

He continued that it was not up to him to suggest an alternative supply, but the Council needed to take its head out of the sand and be open to alternatives.

When Edwin’s resolution (in amended form) — that the Kirk Hallam scheme should be abandoned as soon as sufficient supply could be found at an alternative source — was put to the Council, it was narrowly defeated. As the Nutbrook river was the source of much of the town’s pollution, Francis Sudbury then put forward an alternative resolution, to cease drawing water from the Nutbrook as soon as an alternative could be found, and this was passed.

And then the Local Government Board got involved once more — when it asked for the Council’s comments upon two complaining letters which the Board had received; one from the Hallam Fields Water Committee about the quality of its water, and a second one from the Rev Leopold Crooke. The latter was condemning the town’s present water scheme, and asking for an inspector to be sent to inquire into the whole matter. In reply, a defensive letter was duly drafted and approved by the Council, though not without some resistence. Within it, the Council argued that both the quality and quantity of the town water supply had successfully passed rigorous examination, and that the recent criticism was unfounded. So there !! Let’s move on !!

Rather than wait, I now summarise ‘the Water Issue’ up to the culmination of Victoria’s reign …..

Events did move on, but frustratingly, very slowly. The following years were occupied by false starts and dead ends, when various water sources were considered and/or investigated — at Mapperley, Stanley, Morley, Dale Abbey and at Meerbrook Sough. For example, in June 1894 the water at the New Stanley Colliery at West Hallam had been analysed and the results published. It was considered excellent for dietetic purposes with a very high degree of organic purity. Free from animal pollution, it was a bit too hard for washing and steam purposes though it could be softened using Clark’s process (cold lime softening) … all very promising except that the price charged for the water supply was too high for the Council !!

In the Spring of 1895 the Derby Mercury was pretty confident that Ilkeston Borough was going to secure “one of the finest sources of water known to be in existence in the County of Derby” — the Meerbrook Sough, which makes its surface appearance on the main Derby road from Matlock to Whatstandwell, though other towns like Belper and Wirksworth had their covetous eyes on it. The paper then went on to desribe the water source’s dimensions …. 8 feet deep, 6 to 7 feet wide, about 250 feet above sea-level at Whatstandwell Bridge; the undertaking was commenced in 1780 to relieve lead mines of surplus water. That water was calculated to be 16,750.000 gallons a day, with excellent quality.

Thus by the Spring of 1897 the town had two pumping sources to rely upon — at Kirk Hallam (to raise the water from the shaft there) and at Little Hallam (to raise the water up to the town). But both pumps were facing problems of a conflicting nature. There was not sufficient water at the Kirk Hallam shaft to keep it going constantly; it required about 500,000 gallons per day (for all the town’s collieries, railway companies and breweries) while only half that amount was being supplied. The other pump at Little Hallam was being worked for 19 hours each day !! The town’s shortfall of water was being made up by drawing from the River Nutbrook, an unsatisfactory and dubious source. Over £1000 had been spent by the Council on the Little Hallam bore-hole to a depth of 1202 feet; a further £700 was needed to extend that depth to 1800 feet. In addition more money was needed to sink a shaft and provide a plant to test the amount of water that would be available. The Council therefore applied to the Government Board for a loan of £6000 to cover these costs. (If granted, this would raise the Council’s total indebtedness to about £94,000.)

Extensive boring was undertaken at Little Hallam until 1900 when the Council finally accepted that this location was not the anwer to Ilkeston’s need for good quality water. By the following year Ilkeston had joined with Heanor in purchasing the Meerbrook Sough Company, thus ensuring the supply, to the two towns and their districts, of sufficient water for the foreseeable future. Thus, by the end of the Victorian era, Ilkestonians could sleep soundly at night in the knowledge that the town’s water supply would be secure.

P.S The Unitarian Minister, the Rev. Cooke, left Ilkeston in 1893 to settle in Wolverhampton. While supervising the erection of a new schoolroom there, he was soaked by inclement weather and caught a severe cold. He went away to recuperate but was then seized with inflammation of the bowels. He died in February 1895, aged 32.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Characters

1889: Who’s next ?

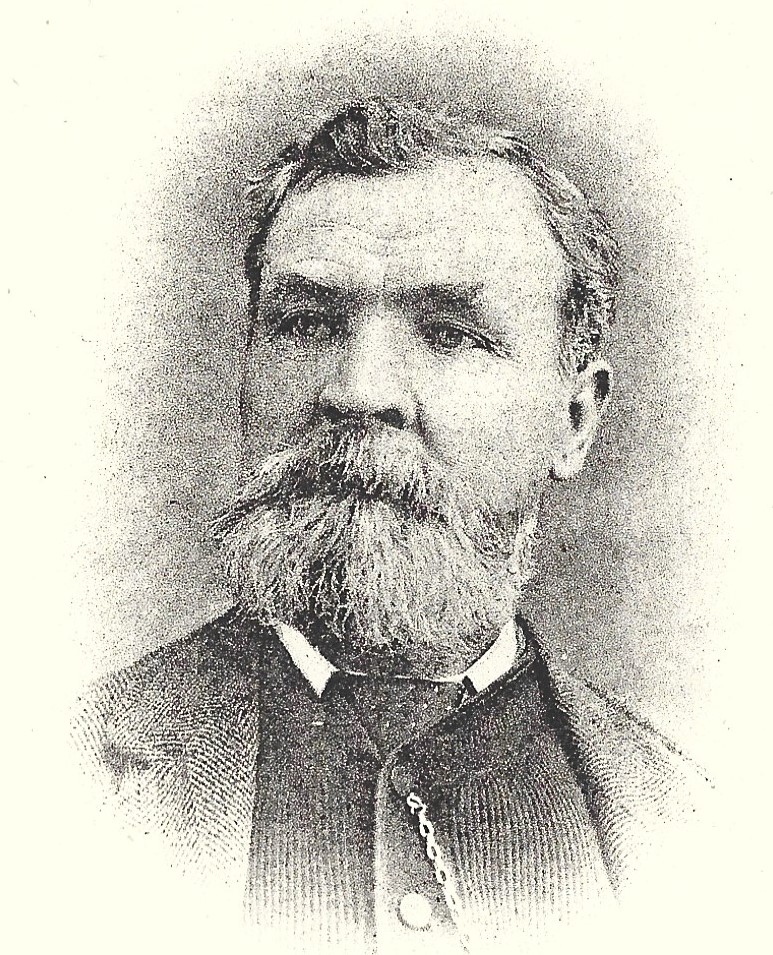

Just as in the previous year, in a private meeting at the beginning of November, the new Mayor of the town was chosen — this time it was William Tatham (left).

The choice was confirmed at a full meeting of the Council shortly after, though not without some ‘choice words‘ being uttered !!

William was a member of the United Methodist Free Church and at his confirmation as Mayor, the Church bells of St. Mary remained stubbornly silent. (His predecessor, William Wade, was a ‘Churchman‘ and had thus been afforded the honour of a ‘vigorous peal’ at his confirmation)

And because he was doing such a fine job, William Tatham was unanimously re-elected Mayor by his colleagues, in November 1890.

1889; And a very merry Christmas to you all !!

Councillor Edwin Trueman (right) was not a member of the council’s General Works Committee but for the last 12 months had been allowed to attend the Committee’s meetings and view proceedings, — so that he could later inform his constituents of what matters had been discussed. Throughout that year he had not interfered in any way and had the permission of William Tatham, the chairman.

Suddenly, at the last meeting — in December 1889 — he had been asked to leave ! — and he refused !! — he claimed that it he had the right to be there !!! However the members of the Committee then voted to exclude him, and when he once more refused to go, a policeman was sent for. But they couldn’t find one !!

Edwin wanted the whole matter to be recorded in the committee’s minutes but this motion was defeated — Edwin did have allies, but not enough !!

And if you think this is not illustrative of the way the members and officials of the council often worked ‘together’ then just read on !!

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

1890

In a minority of one … again !!!

The hostility between Councillor Charles Mitchell and Wright Lissett, the Town Clerk, had been simmering quite nicely for several years, when in May 1890, it bubbled over vigorously.

At the quarterly Town Council meeting Charles moved several resolutions, all aimed at curbing the role of the Town Clerk, several of them also implicitly criticising him, and one of them accusing Wright of ‘tampering’ with the Council Surveyor’s accounts.

Several other Councillors and the Surveyor came to the Clerk’s defence but they were too late.

Wright Lissett (addressing Mr. Mitchell, heatedly): I have been a public servant in the town for 20 years. Now I am charged with tampering. What do you mean ? Tell me this minute, if you please, what you mean by the word ‘tamper’, or else hold your peace and let me alone !

Charles Mitchell: to alter the figures in a man’s books is ‘tampering’.

Wright Lissett: ‘tampering’ means nothing of the kind. It means to do something in secret. The figures were altered openly and put in red ink before the auditors in that way.

Charles Mitchell: did the surveyor ‘scrat’ them out again ?

Wright Lissett: he did so, improperly.

At this point only the last of Charles’s resolutions had been seconded (by Edwin Trueman) and so it was the only one that could be put to a vote. Charles found himself, once more, in a minority of one — even his seconder voted against him !!

There was more to-ing and fro-ing before Councillor Edwin Sutton suggested (tongue in cheek) that perhaps Charles should be the Town Clerk for the next year !! (much laughter, but probably not from Charles)

And now, Wright Lissett was given the opportunity to reply to the accusations made by Councillor Mitchell — and he did so, in a lengthy and at times impassioned address.

He suggested that the four resolutions were aimed directly at him, and were the culmination of a series of attacks upon him over several years. Their object was to hold him up to hatred, ridicule and contempt, and it had all arisen from malice and spite. Charles had long held a grudge against him, and was now using language of a defamatory character, if not actually slandering his good name — and he had never done Charles a single injury or wrong !!

Tampering with the accounts was only the latest charge — in the past he had been accused of trying to influence an election , and with misappropriating the public water, all charges without a single foundation in fact.

But where did all this malice eminate from ?

Wright then recounted a ‘little incident‘ several years previous, when his servant had taken a cart down to Hallam Fields — where Charles lived and owned a grocer’s shop — and had sold some potatoes at 2d a peck cheaper than Charles was selling them in his shop. And Wright’s servant was doing this without his knowledge. But since that time Charles had vowed to do everything he could to get him out of his office !! Wright then concluded by stating that his patience was now at an end — if Charles persisted in his attacks then he would be taken to court. Be warned !!

“Mr. Lissett sat down amid loud cheers”

So there you have it — several years of festering animosity caused by a few cheap potatoes ??

June 1890; new County magistrates for Ilkeston

Both the Mayor, William Tatham, and John Ball, lace manufacturer, were appointed as County magistrates … an announcement which “gave general satisfaction in the town, not only on account of the increase in size of the local bench, but also on account of the gentlemen upon whom the honour had devolved”

They both took their seats as County magistrates at the Petty Sessions of the following month.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

Changes

September 1890; a momentous decision … two into one does go !!

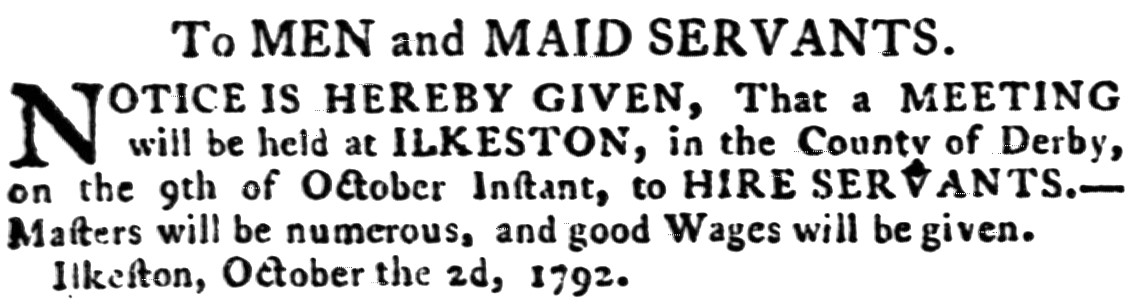

Derby Mercury October 2nd 1792

On the evening of September 10th a public meeting of townspeople was held at the Town Hall, to consider holding the Wakes and Statutes pleasure fairs in the same week. This would therefore abolish the custom of holding them separately, one in the middle and one at the end of October. The proposal was to begin the joint holiday on the first Thursday after October 11th and to end on Saturday. This would mean three days of holiday, followed by a Sunday day of rest, and then ready for a new working week on Monday !!

Many spoke out in support of this resolution, though there were suggestions that the three-day holiday should begin on a Monday and back to work on Thursday. But then, after three days of ‘merriment’, would workers feel like going back to the factory or down the pit ? And if they did, how productive would they be ? Most felt that it would be much better to get three days work done and therefore have some wages to rely on, for their family and for the ‘holiday’.

This was an important issue, discussed at length, by those of political and economic influence within the town (but how many others ?) and eventually the meeting passed the resolution … “that all the employers of labour close their places of business during the last three days of the week called the Wakes Week, and that the Statutes and Wakes be observed on those days”

October 1890 : Ilkeston goes automatic

The Town Council gave permission to Balfour Co. Ltd. to install automatic machines supplying stamps and postcards by the side of pillar letter-boxes .. at £1 per year per machine rent. They were not P.O. machines.

“The Postcard and Stamped Letter Company in being granted a licence in 1884 had to agree to have a plate affixed to their machines stating that they had no link with the General Post Office. A later machine from c1890 was known as the Balfour and for one penny could dispense either a 1d stamp with paper and envelope or a onehalf penny stamp and a stamped postcard. To effect a dispense it was necessary to pull a handle until a bell rang”.

November 26th 1890: the quest for a new cemetery

In 1881 the town’s population was recorded at 14,119 and now, almost ten years later, it was estimated to be over 20,000 and growing !! More births, but more deaths too.

The provision of a new cemetery for Ilkeston had been raised at the beginning of 1888. Various sites around the town were considered — at the rear of South Street (where Albert Street was later laid out), at Hilly Holies, and in Heanor Road (behind the Brick and Tile Inn). And guess what ? A Committee had been formed to assess them all. It worked very slowly so that it was still deliberating by June of the following year. Now, more sites were identified and examined, the number wittled down until an area at Pewit, where West End Drive and West End Crescent now stand, was chosen. The land was owned by the Duke of Rutland who was prepared to sell the 15½ acres for a total of just over £3000. Together with the cost of a new road to the proposed cemetery, a loan of about £4000 would be needed by the Council and this was duly requested.

In November 1890, the request was considered at a local government inquiry which heard that the old parish churchyard was closed about 40 years ago, the new extension was so overcrowded that its walks and paths were being used for burials, the graveyard of Christ Church in Cotmanhay was full, while the General Cemetery in Stanton Road was two-thirds full.

At this point the Derby Daily Telegraph pointed out that the proposed site of the new cemetery drained into the Nutbrook which was the source of a public water supply. And because of this, the request for a loan was denied.

The quest went on into 1891 with a successful conclusion

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Council and the town’s pubs (Part 3)

Mostly via the Borough Surveyor, Henry James Kilford, the council of course continued its work, examining the drinking premises.

The Derby Arms Inn … The inn was owned by John Trueman (yes, him again !!) though he wasn’t the landlord. The Council now ordered asked him to make the covering to the entrance of the cellar on a level with the pavement.

Great Northern Hotel … Henry James Kilford was asked to explore the advisability of removing the lamp standard outside the Great Northern, situated in Cotmanhay Road

The New Inn … Adkin Toplis was landlord of this beerhouse. It wasn’t the one in middle Bath Street at the corner of Providence Place, but the one opposite the Old Harrow Inn, at the corner of East Street. He asked if he could use the Borough Arms on the painted sign outside the beerhouse, and presumably rename the premises as ‘The Borough Arms’. Permission was granted.

The Brick and Tile Inn … the agent for the Duke of Rutland was approached to quote a price per acre for land at the back (east) of the Inn. It was presently being farmed by Robert Skevington and the Council saw it as a possible site for its new cemetery (see above)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

We now move on to continue the work of the Council