And what was it like ? — the church which the Rev. Edward Muirhead Evans ‘inherited’ from the late John Francis Nash Eyre in 1887 ?

Of the actual foundation of any portion of this church or its adjuncts, no direct documentary evidence seems, as far as at present can be ascertained, to exist….

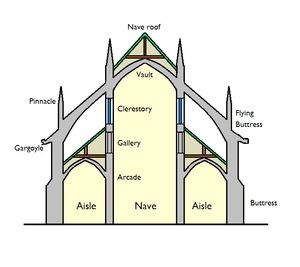

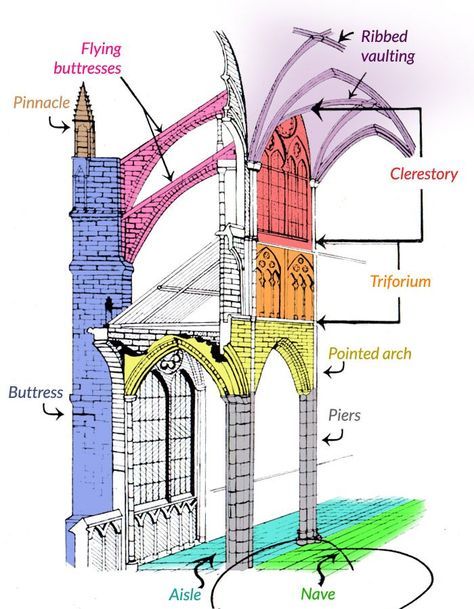

In the 45th year of Henry IIIrd’s reign, about 1261, the Manor of Ilkeston came by marriage into the possession of Nicolas de Cantilupe. One portion of the church now remaining must have been in existence prior to the Cantilupes becoming lords of the manor — namely the south arcade of the nave which dates back as far as Henry II (1154-1189) or Richard I (1189-1199), being of the transitional period (in the twelth century). The chancel is of the early part of the Geometrical and must have been built in the reign of Henry III and founded by Nicholas de Cantilupe, fourth son of the founder of that family and first of that family who was Lord of Ilkeston.

His tomb still remains. The arms on the shield of the effigy correspond with the Cantilupe arms in a tomb at the south end of the South Aisle of the Presbytery of Lincoln Cathederal, where was a chantry founded by Nicolas, Lord Cantilupe who died in 1372, grandson, or possibly great grandson of the founder of the Chancel of Ilkeston Church.

The nave was rebuilt about 1330 by Nicholas de Cantilupe, grandson of the founder of the Chancel, a princely benefactor of the church, founder of the Beauvale Monastery in his park at Greasley. A beautiful Chantry Chapel was added in 1360, by Joan, Relict of Nicholas de Cantilupe.

In 1854 was the last restoration — the rebuilding of the North and South Aisles, the rebuilding of the Chantry Chapel, adding clerestory and restoring the Chancel Arch, recasing the Tower, and adding the Vestry — all at a cost of £4000.

The working classes of Ilkeston gave over £500, the Duke of Rutland £200, and the Vicar and his relatives over £1400.

The endowment of Ilkeston church is so ancient that its origin cannot now be traced. It consists of some 44 acres of glebe, and £100 tithe, paid by the Duke of Rutland’s land.

Adapted from the Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald (September 17th 1887)

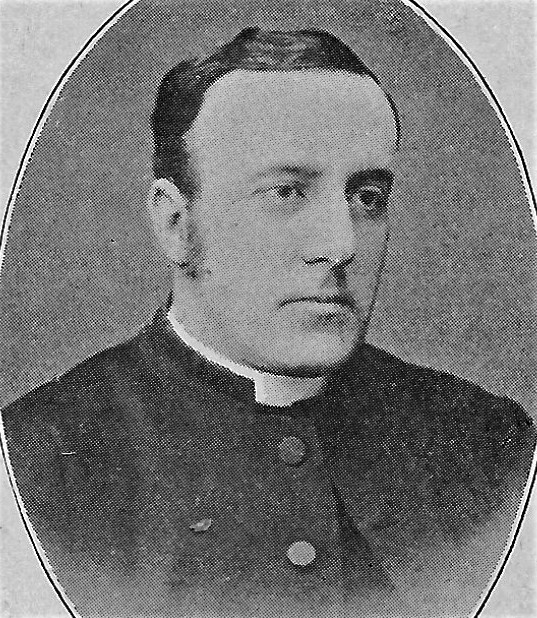

Edward Muirhead Evans, right, (1849-1907) was vicar of St Marys Church, Ilkeston between 1887-1907, during which time there were modifications to his church, the vicarage was rebuilt, and St John’s Church in Nottingham Road was established.

On Sunday morning, May 1st 1887 the new vicar of St. Mary’s Church was formally inducted into the living of Ilkeston. The church was filled and the congregation was treated to a fully choral service. In the evening Edward preached his first sermon to a crowded congregation.

——————————————————————————————————————–

1887: An early controversy for Edward

Within a few months of his arrival Edward was embroiled in a controversy all of his own making. The impetus for this was the death of two-year-old Arthur Bostock, son of Owen and Sarah (nee Trueman), following an attack of croup. Sarah was the daughter of John Trueman who owned the Horse and Groom at Gallows Inn and which was managed by his son-in-law. Edward visited the grieving parents, trying to persuade them to have the child buried at St. Mary’s. However Sarah wanted otherwise — she had written to the Rector of Trowell Church requesting that her son be buried at his church, just as her older son, John, had been buried there two years earlier. (Aged eight, John had drowned in the Nottingham Canal near the family’s Inn). And just as two years earlier, the Rector gave his consent.

At noon on the day of the funeral the Rector received a letter from his counterpart at St. Mary’s Church, threatening to report the Trowell incumbent to the bishop if he buried an unbaptised boy. And Arthur had not been baptised, though neither had his brother John. The Rector bowed to the threat — he couldn’t now permit a service to be held in the church before the burial, but offered the parents alternatives. The boy could be buried without a service, or have a Dissenting Minister conduct the service, or have a burial at the General Cemetery. The parents chose the first course.

The Nottingham Journal was not impressed: “this suggests the Vicar of Ilkeston might be better have refrained from any interference in the matter … the occurrance of such cases cannot fail to excite local irritation, and assuredly do not tend to the spread of true religion”.

And the episode was soon elevated to “Scandal” status !!

1887: Edward begs for assistance

A few days after this episode Edward was shooting off another letter …. this one to the Town Council (September 1887), He asked that the Council illuminate the town clock in the parish church, and that the Corporation ‘assist’ in the repairs to the church bells (estimated at £196). The first request was met with some favourable consideration, but the ‘bell repair’ issue elicited incredulity; — “a remarkable piece of business: people must think the Council is a lunatic asylum to make such a request ” (Councillor Edwin Sutton)

“I presume the Council will be open to receive applications from people who want to build chapels or make alterations ?” (Councillor Charles Mitchell, sarcastically ?)

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1888: A discovery at the Vicarage

In January 1888 work was taking place in the Vicarage grounds when a rectangular brass plate was unearthed. It was about 1ft by 1ft 6in, and at its top was a coat of arms, showing a shield with floral decorations at both sides and above was the head of an animal (a leopard?). Beneath was an insription which read ……

Here are interred the remains of

MR BENJAMIN DAY,

Late of Arnold, in the County of Nottingham,

Who Departed this Life July 6, 1760,

Aged 94 years

Beneath this was a sonnet and then a further inscription …

Here lie also the Remains of Elizabeth, his second wife, a sincere Christian

This plate was to be found in the centre aisle of the Church in 1831 but somehow found its way into the Vicarage garden. There was conjecture that, when the work took place to restore the Church (1853-55), it was removed and perhaps, through carelessness, found a new ‘resting place’. Vicar Edward had it cleaned, intending to restore it to a safer ‘home’.

—————————————————————————————————————————

1888 (and 1892): Unlawful burials ?

In 1862 a new burial ground had been added to the Churchyard at St. Mary’s from land donated by the Duke of Rutland. (This was the churchyard extension, today separated from the Church by Chalons Way).

The Ilkeston Pioneer (April 10th 1862) wrote about it …..

The new ground to be added to the Churchyard is situate at the east end of the Cricket ground, and will be ready for interments in June next. The promoters of this very necessary addition to the burying ground deserve the best thanks of the public, for their efforts will undoubtedly save the inhabitants a heavy yearly rate for twenty years to come, which must have been imposed to make and sustain a Cemetery, as at one time proposed. For several years past increased attention has been paid to the order and neatness of the Churchyard, and we have no doubt the new proportion of the ground will in a short time be rendered a beautiful repository for all that is mortal of departed friends.

The new burial ground had been consecrated by the Lord Bishop of Lichfield on Thursday May 29th of 1862.

‘An Aggrieved Churchman’, who wrote to the Pioneer in November 1875 described it as “more like a dung yard than a grave yard” – the dung being that of the 20 or 30 geese who felt at liberty to wander in the area. In the same paper ‘A Mourner’ had also spotted the geese as well as their companion ducks and a grazing horse in the burial ground.

“A dog is not even allowed in the Dissenters’ Cemetery on the Stanton-road, which is kept in a very tidy state: but in the sacred spot attached to the old Church animals of every description appear to be welcomed”.

Part of the old churchyard had already been closed, in 1856, and after the new burial ground was consecrated, the rest of the old ground was closed — by order !!

However, in the summer of 1888, shortly after Edward’s arrival in Ilkeston, it was reported by Edwin Trueman that the old churchyard was once more being used. In July Dr. Hoffman of the Burials Acts Department of the Home Office descended upon the town to sort matters out. John Fish, the Parish Clerk, was on hand — he admitted that burials had recently taken place but that he was under the impression that the old churchyard had been closed for a period of 20 years only. Now that time was expired and it could be used once more. Dr. Hoffman quickly disavowed John’s claim; the Order was clear, that the closure was absolute and permanent. However John now thought that the matter was triffling and that some people — who could he possibly mean ? — had merely complained for the sake of stirring up a controversy.

Mr Hoffman left the town, promising to report back on his subsequent consultations with the Home Office. This he did in mid-September of 1888 when it was confirmed that no more burials in the old graveyard were to be permitted — except in existing vaults.

However, in mid-November 1892, Dr. Hoffman was back in town. Councillor Joseph Scattergood, a member of the Town Council’s Health Committee, had alerted the Government’s Home Office that the Parish Churchyard was once more being used for burials — the churchyard was already overcrowded and interments were taking place too near the surface. Joseph pointed out that there was now no need to use St. Mary’s burial ground as the new Park Cemetery had just opened for burials. On November 16th, the Vicar accompanied the Doctor, and a group of Ilkeston’s dignataries, to inspect the Churchyard — and Dr. Hoffman was clearly annoyed by what he found !! The Home Office regulatons were still being disregarded, leaving the Church authorities open to financial penalty. Vicar Edward was suitably penitant and promised that no more interments would take place (except where a depth of at least four feet could be guaranteed).

Christ Church, Cotmanhay: a similar problem ? December 1895

Though only indirectly related to St. Mary’s Church, it might be convenient to consider the problem facing its Cotmanhay neighbour.

The closure of the Christ Church cemetery, which was now nearly full, was anticipated at the end of this year. What could be done therefore to extend the burial provision at this northern part of the town ? The Park Cemetery was now open, but distant; getting the dead from outlying parts of the parish to the municipal cemetery would be very costly such that poor people might be driven to the poor law to bury their dead. Perhaps the folk of Cotmanhay wanted a burial ground more close at hand. One suggestion was to approach the Duke of Rutland who might be willing to provide land for a graveyard extension. It was felt that if approached ‘correctly’ the new Duke would be more receptive to the idea than his father ahd been. In nthe past, the Vicar of Cotmanhay, the Rev. Edward Thomas Straton Fowler, had argued without success for extra burial accommodation — now it was up to Cotmanhay folk to take the issue forward. What could be done ??

When in doubt, form a Committee. Which is what was done ….. led by Aldermen Samuel Richards and Frederick Beardsley, both born and bred in Cotmanhay.

————————————————————————————————————————

1888: An eventful Christmas Day at St. Mary’s

Leading up to the Christmas Day of 1888, self-styled ‘Professor’ Alonzo Spencer (really a stationary engine driver living in Belper Street) had been planning a ‘spectacular feat’ to amaze the town’s residents. And on Christmas Day he was ready to carry it out.

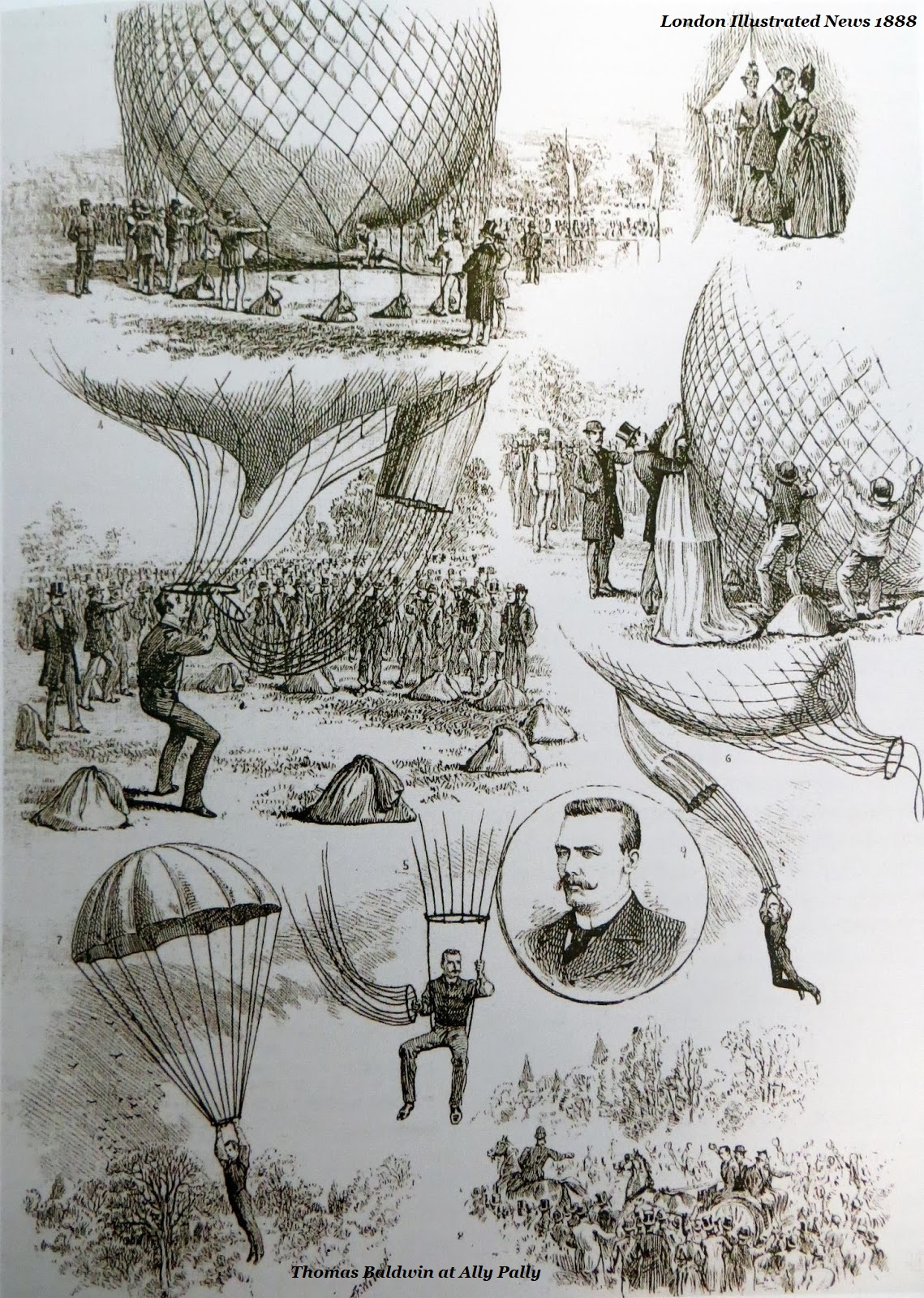

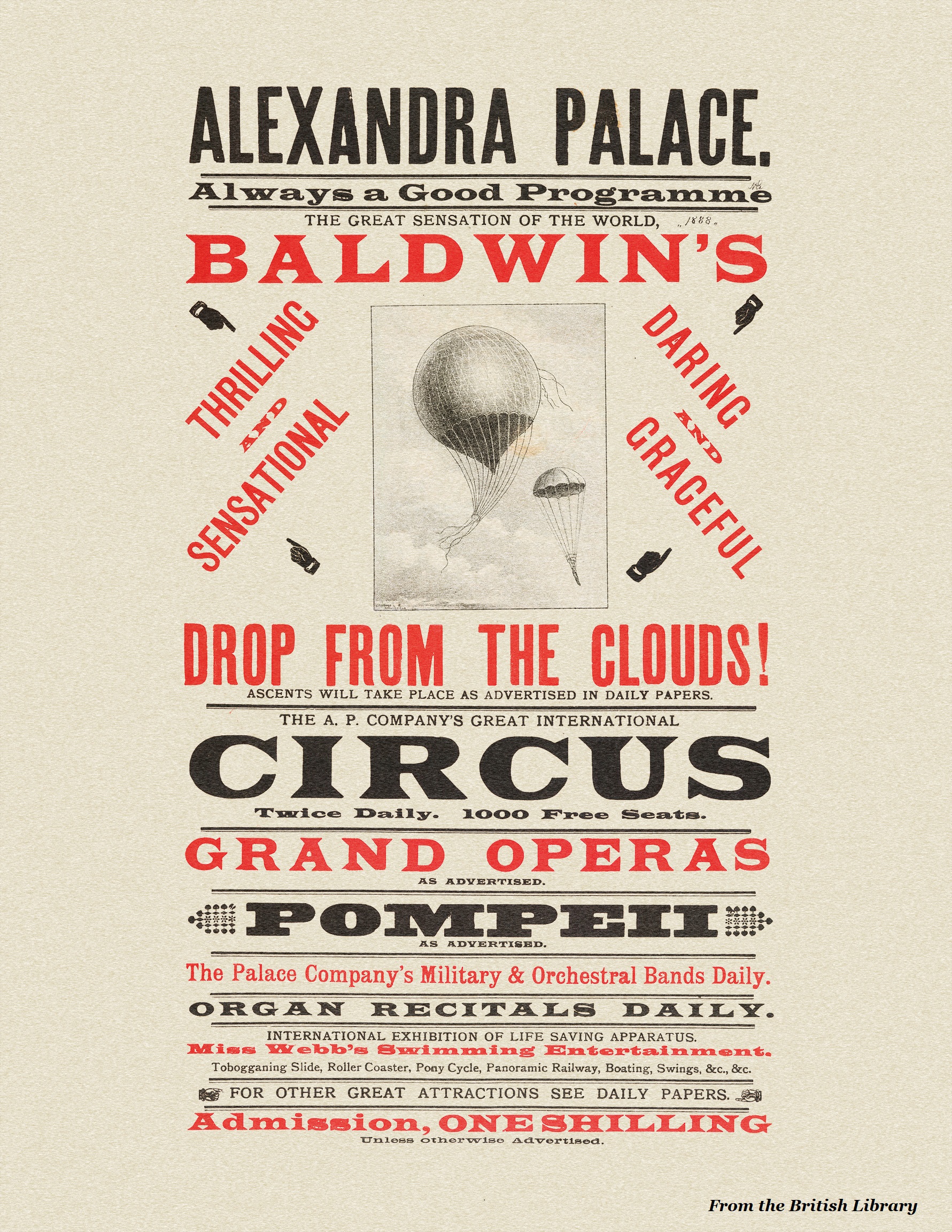

Alonzo would climb to the top of St. Mary’s Church tower, a height of 75 feet, accompanied by his parachute, attached to which was a home-made, wicker-work basket. The plan was to jump out of the tower and float gently to the ground, seated in the basket. He had heard that American daredevil Thomas Scott Baldwin had undertaken a similar feat earlier that year, at Alexandra Palace — surely a hardy Ilkestonian could carry off something more dangerous and dramatic ?

Thomas Baldwin at Ally Pally 1888, from the Illustrated London News … his drop from the sky, the first American to descend from a balloon by parachute, his tenth jump.

When Alonzo got to the top of the tower however, he must have looked down, then glanced at his cobbled-together basket, looked down again, and at that point decided that discretion was the better part of valour. A test descent was needed. Alonzo therefore lowered the open parachute and its unoccupied appendage over the tower’s side and let go — at which point the ‘flying machine’ appeared to demonstrate a will of its own. It ‘flew’ (plummeted ?) away from the tower and became entangled in telegraph wires which crossed the churchyard some 30 yards from the tower.

Alonzo rescued his ‘machine’ with the aid of a scaffolding pole and carted it home — to fly another day perhaps ? The people of Ilkeston were probably not amazed but they were certainly amused.

But how did Alonzo gain entrance to the tower ? —- his half-brother, Silas ‘Silly-Ass’ Spencer, had been a bell-ringer at the church. Did he still have ‘connections at St. Mary’s ? And where was the Rev. Muirhead Evans all this time ? Perhaps positioned at the church gates, selling tickets for a better view ? All proceeds to Church funds !!

Perhaps Alonzo’s eccentric acts of derring-do had an impression upon his children, especially his young sons ? In 1892, twelve-year-old Hubert Spencer and his younger brother Harry, aged 10, were very fond of throwing themselves around and performing acrobatic tricks like circus entertainers — prompted perhaps by the recent visit to Ilkeston of a renowned circus troupe. At home in Havelock Street one Sunday morning in early September, Harry had climbed on top of the fire-range and then onto the table, ready to astound his brother, but then fell onto his left-hand side against the range. His step-mother Alice soon found him on the floor, in excrutiating pain and vomiting, so she lifted onto the sofa where she offered the lad some water. However before Doctor Tobin could arrive young Harry had died. A ruptured liver or some other vital organ being the cause of death.

P.S. Alonzo was still active August Bank Holiday of 1894 when he appeared at Ilkeston’s annual flower show at the Pimlico Recreation Ground .. to close the show with his display of fireworks, namely asteroid rockets, shells and maroons.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1889: Edward pines for ‘the good old days’

In January 1889, at the annual meeting of the Church Institute, Edward gave a speech on “the Good Old Times”. He descibed Ilkeston as a most democratic place, and wherever anyone went they heard the cry ‘Vox Populi’ — the voice of the people was paramount. He lamented that the people would not listen to their betters, nor pay respect to those who were wiser than themselves.

He argued that Conservatives — of which he was one — taught that men should respect those who ruled over them; in the ‘good old days‘ people gave heed to the squire and to those who were placed in positions above them. Thus, it was the duty of the members of the Church Institute that they should teach something better than that the mere people should decide everything.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1889: Grave discoveries at the Chancel

In May 1889 alterations were being made to the chancel at the Parish Church when two tombstones were discovered under the floor. The first, remarkedly well-preserved, was a slate about six by three feet, with an inscription under the arms of the Flamsteed family of Little Hallam.

It read :- “Here lyeth the body of John Flamsteed, of Little Hallam, gentleman, who dyed December ye 15th, 1745, aged 72”

The grandfather of this John Flamsteed was the uncle of the Astronomer Royal of the same name; while his father, of the same name too, was the one who, in his will dated 1684, set up the charity bearing his name.

The second tombstone was another slate slab, about three by two feet, with a brass shield attached to its middle, and bearing the inscription: “Here lyeth the body of Templer Flamsteed, son of John and Ann Flamsteed, who was borne October the 22nd, 1712, and departed this life April the 6th, 1713”.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1889: More Church improvements

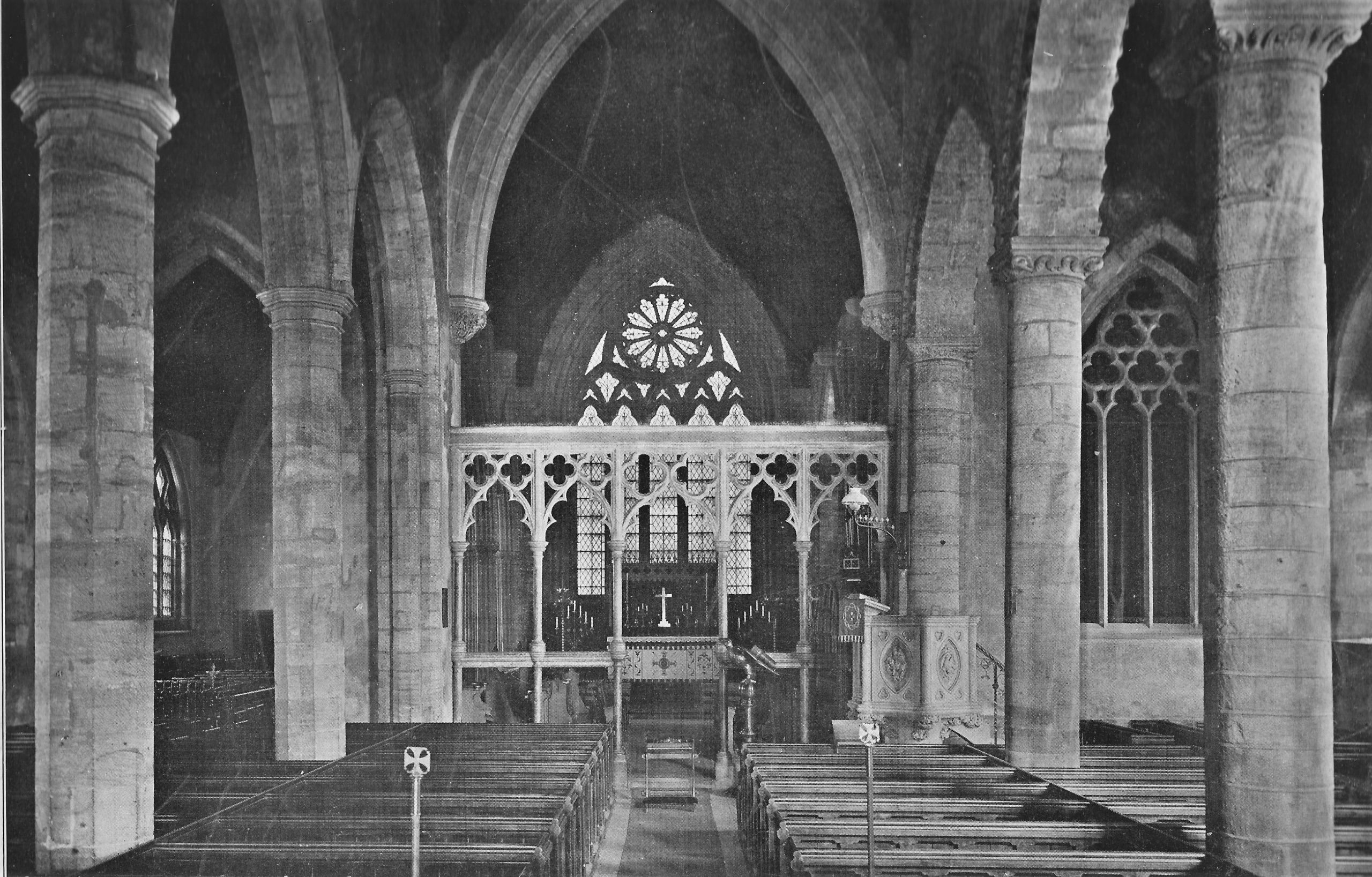

In July the Parish Church was reopened after a partial and temporary closure for refurbishment, the ceremony conducted by the Lord Bishop of Southwell. The old seats in the chancel had been removed, replaced by carved oak stalls for the choir, and chairs put in the rest of the chancel. The stalls had a total of eight carved pinnacles at the ends, courtesy of the Cossall Carving Class.

The Communion table had been raised and was now approached using steps, made of polished Hopton Wood stone. Other parts of the floor had been retiled and there were new alter cloths, carpets and kneeling cushions, several provided by ‘ladies of the congregation‘. A new alter table of Austrian wainscot oak was installed, all the chancel brasswork had been relaquered, and the seating in the rest of the church had been cleaned and varnished.

The church organ had been rebuilt by Messrs Brindley and Foster of Sheffield, on their “patented tubular pneumatic system” for a cost close to £500, and was to be repositioned from the east end of the chantry to a new organ chamber, between the east end of the south aisle and the vestry. For the experts among you, ” it now consisted of 26 speaking stops and 12 accessory movements, many of these being the firm’s patent” (DM) It was to be played by the organist, seated on a console in the chancel, so that he could hear the effects of the music with the choir and observe the movements of the clergy, away from the organ. “The stops are the large open diapason or great organ, harmoni-flute, trumpet, vox Angelica, voix celeste, and pedal open diapason (16 feet), and the agreeable tone of ‘Bourdon’ on pedals” . When it was first installed at St. Mary’s, in 1866, it had come from St. John the Evangelist’s Church in Paddington and had reputedly been played upon by the composer Mendelsshon. Its arrival after its overhaul however had been delayed, so that it wasn’t there for the re-opening service — it was expected in October but was in its final place only at the beginning of November.

By April 1895 the debt on the organ had been reduced to £65.

Looking towards the east end of the Chancel; the South Aisle on the right (from Trueman and Marston)

The Cantilupe Gothic alter tomb had been moved, about four feet, to underneath the east chantry arch.

Percy Currey of Derby was the architect for this work, while John Manners, builder of South Street, did much of the interior building work. The total cost was in excess of £1000, some paid off by subscriptions but a large proportion merely increased the Church’s debt.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1890; another Evans

On January 8th 1890 a son, Harold Gaspar, born to Edward and Sarah Louisa Evans.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

1890: and yet another controversy for Edward

In June 1890 the Rev. Edward stood as one of the four Church candidates for the upcoming School Board election … and in his campaign he made some very controversial remarks about Board Schools.

At holiday times we see young men breaking down the branches of trees and doing other mischief, and young married men brutally ill-treating their still younger wives; and these have been educated in Board Schools.

In reply to Edward’s views, Mr Harvey, the miner’s agent, stated that the Vicar had, by his words, simultaneously managed to insult the town, the members of the School Board and the parents of the Board School’s children …. not bad going !! He personally knew of Church parsons who got drunk and had to be carried home — much worse behaved than these imaginary Board School scholars. Voluntary Church schools educated the snobocracy — all collar, cuff, and tie !!

Mr. Harvey then referred to Edward’s speech at the Church Institute in January of the previous year (above). To the miner’s agent there was no man sufficiently high for another man to demean himself by bowing and scraping to. Church parsons were not the friends of working classes, they were the greatest enemies they had, and, with the Tory Party, had blocked many reforms they should have had. If they had depended upon men like the Vicar of Ilkeston, would they have had the secret ballot, or free press, or the franchise, or compulsory education ?? He hoped that ‘the voice of the people’ would be heard in this election and would leave the vicar at the bottom of the poll.

And of course the Vicar was quick to defend himself. In a speech to his electorate a few days later, Edward declared that he had been totally misunderstood. The standard of education found in Board Schools was excellent, and thus he was so surprised when he discovered that some young people of these schools were misbehaving around the town — especially on Bank holidays. He commended the religious education in these schools and, if elected onto the Board, he would never interfere in this education. At the culmination of his speech, it appears that he had not fully convinced his audience !!

When the election results were announced, close to midnight on June 18th, the wish of Mr Harvey, the miners’ agent, was granted … almost !! Edward was bottom of those elected (that is, number 9), and the Derby Daily Telegraph had some very stern advice for Edward ….

The Vicar, it is to be noted, only got in by the skin of his teeth, although he appears to have been confident of occupying them premier position, and of being elected chairman. The reverend gentleman, moreover, went to the length of indicating the changes he intended to propse when acting in that capacity. In future it is to be hoped he will recognise the wisdom of “never prophesying unless he is quite sure”. (June 20th)

Within a few months, was Edward starting to exploit his new position on the School Board ??!! In March of 1891 he asked for a reduction in the rate of 10s per day charged whenever he used Kensington School for Church meetings; his curate wanted to use that school’s buildings for a weekly Mission until the summer. The Board deliberated and decided that, because the Mission was of a denominational character, a reduction should not be given — it would be unfair to other local religious bodies.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

September 24th 1890: a musical concert.

The refurbished Church organ, installed less than a year before, still had a significant debt attached to it.

Step in, Ilkeston’s leading musical talent, Harry Stanley Hawley. (right)

On this September Wednesday, aided by several artists from the R.A.M., he gave two concerts — afternoon and evening — in aid of the Organ Fund.

And in December 1893 Harry Stanley was back at St. Mary’s Church, doing the same thing … for the same reason.

The debt still stood at £50

—————————————————————————————————————————–

November 1891 — April 1893: a Church extension ?

Members of the Church were now urged to cast their attention to the ‘large and increasing district’ between the Parish Church in the Market Place and Trowell Station at the bottom of Nottingham Road. This area included Gallows Inn, and one side of Park Road and Derby Road, with a population of about 3000-4000. A mission to serve the area had been started in 1888, in a little old shop room at the corner of Pedley Street in Nottingham Road, led by the curate of St Mary’s, the Rev. William Henry Butler. The first sermon there prophetically took, as its text, the parable of the mustard seed (Mark 4: 30-32). William Henry left a short time later and his successor, the Rev. Sydney Robert Noel Rees, was assigned special charge of the district. And he did so with great vigour, enlarging his ‘congregation’ such that the one-room mission couldn’t accommodate them all. What was needed was a new, more commodious, more substantial and permanent church.

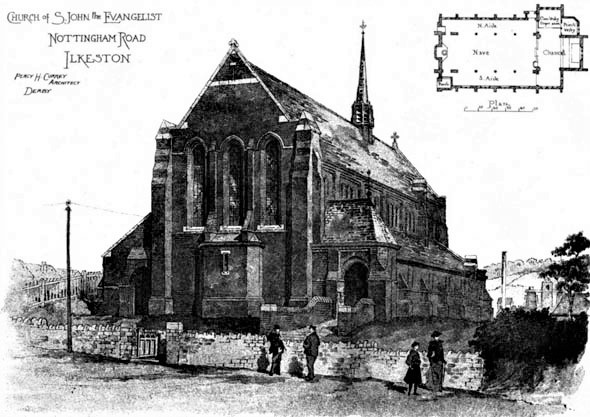

The Duke of Rutland had already a site to offer for the new church; it was on the west side of Nottingham Road but had one significant drawback. The custom of the Church of England was to build a church, running west to east, with the main entrance to the west and the chancel at the east end. A new church built on the Nottingham Road site would have the disadvantage that the congregation would be inconvenienced by having to walk along the whole length of the church to exit by the main west door. Edwin Canner J.P. of Stanley Grange came to the rescue however. He had a piece of land on the east side of Nottingham Road, and so with the Duke’s agreement, he adopted the simple solution of swapping properties. His Grace was thus able to bestow upon the trustees of St. Mary’s Mission Church a most suitable site for their purposes. It was about half an acre, large enough for a church, mission room and parsonage, though funds were not sufficient for the trusteees to finance all of these buildings. Thus plans were prepared by architect Percy Heylyn Currey of Little Eaton, Derby, for a plain brick building, including only a nave and south aisle, and holding a congregation of 300 — further features, like a north aisle, chancel, organ chamber and vestries, could be added later. The building was to be in the Early English style, the front being of plain red heather brick with stone sills. Percy’s name as an ecclesiastical architect was “being recorded up and down the diocese in many monuments of his skilful designing” (Belper and Alfreton Chronicle)

In the meantime temporary plans were adopted to cater for the growing congregation. After a ‘stop-gap’ use of Board School accommodation, in 1892 a new wooden mission room was built, the Rev. Edward turning the first sod and local workmen giving their services free to build it. Its total cost was £85, and it too was a great success, such that thoughts now turned back to the new church for the community. The Rev. Edward, energetically aided by the Rev. Rees and his carefully nurtured band of workers, were fully prepared to start a fund-raising campaign — a first installment of £1500 was needed to get the building ball rolling. However this was a poor area and so financial help would probably be needed from Nottingham and Derby.

Six months later and the name of St. John the Evangelist had been chosen for the new church. As usual, fund-raising activities had to be arranged to finance the venture — like the bazaar held in St Mary’s vicarage gardens on August 3rd 1892 and opened by Lady Laura Ridding, wife of the Bishop of Southwell. At this event the Rev Edward mentioned in his welcoming speech that a predecessor vicar, George Ebsworth, had long held the desire to build a new church in the southern part of the parish. Now, because of the rapidly increasing population in that part of the town, it fell to Edward to push for the new church, thirty years after George’s departure.

On April 19th 1893, the foundation stone of this new church was laid, by Sarah Louisa Evans, wife of the Vicar of St. Mary’s — the only notable local dignatory absent from the occasion was William Merry, the Mayor of Ilkeston, who had been ill for some time.

The total cost was still estimated at £1500 of which £700 had now been raised.

William Vincent Ireson of East Street was employed as builder and he expected to have the project completed for the opening ceremony by November.

And he was spot on !!! (see below)

Joiners Albert Hazlewood and James Marson (Hazlewood & Marson of South Street) were contracted to supply the woodwork.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

June 4th, 1893: Great Ball of Fire !!

Sunday afternoon and a violent thunderstorm visited Ilkeston. And I mean violent !!

Torrents of rain, detonations of thunder, and a great ball of fire, the latter falling directly on the Vicarage, smashing a chimney pot and tumbling down the chimney, into the dining room. Just as the Vicar and his family were sitting down to enjoy dinner. As the electric current passed through the house, Edward’s wife, Sarah Louisa, sitting by the fire, received a violent shock, and then the bathroom was set on fire. The emergency services — in the form of a police constable, an Inspector, and the Fire Brigade — were quickly on the scene. So quickly in fact that there was no need for the water hose to be deployed ‘in anger‘. Burning woodwork was torn out and thrown onto the lawn.

The lightning passed down Bath Street, to visit the home of Dr. Robert Lowry Moorhead at number 65 Station Road, and — would you believe it !! — the house of Henry James Kilford, Borough Surveyor and Captain of the Fire Brigade, at number 68 !! A bird’s nest in the rafters of the doctor’s house was briefly set on fire until Henry James climbed his ladder to extinguish the danger with a ‘hand grenade‘. Little did he know that his own gas meter was on fire, until he was informed by his alert wife. So that, once more, serious damage was avoided.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

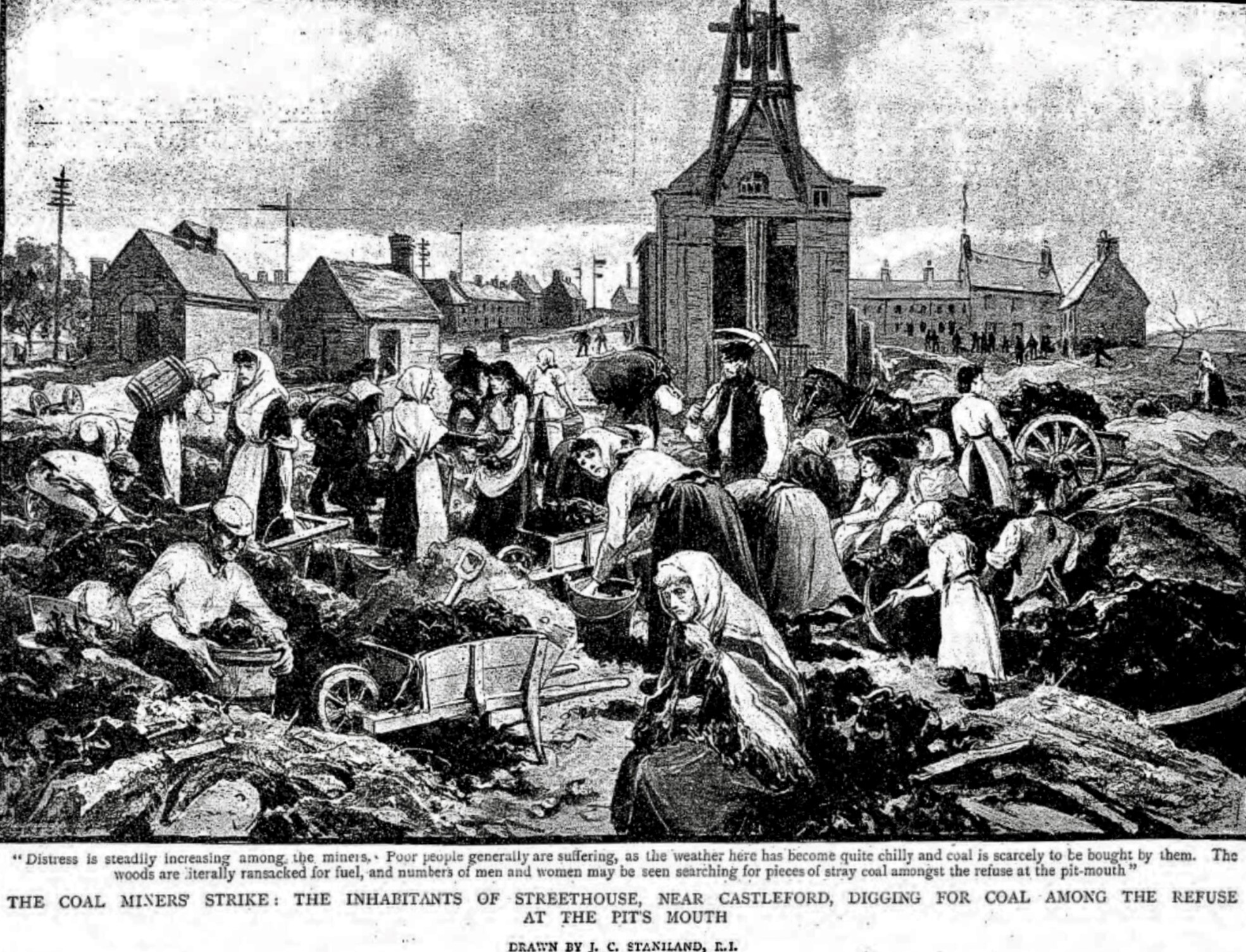

August 23rd, 1893: a soup kitchen at the Vicarage

The coal strike at Ilkeston had entered its fourth week and because over 3000 men were employed in this trade in the area, there was considerable distress in the town. This was exacerbated by the fact that more than half the town miners were not unionised and so got no union pay. In the eyes of the Derbyshire Miners’ Association Ilkeston had long been a “blemish” on their movement and now the non-union workers were reaping what they had sowed by their apathy and indifference. Tradesmen in the town were of the same opinion but everyone was disposed to see that the women and children of the out-of-work men did not suffer. Consequently the Vicar was on hand at his home to dole out bread and soup to a host of wives and their children who besieged his gates, a twice-weekly occurance. He was assisted by the Vicar of Holy Trinity and the curate of Christ Church in Cotmanhay.

The Salvation Army was giving free meals, and many local tradespeople were privately giving bread and soup. A private meeting of the School Board was convened to consider free breakfasts for Board school pupils. As a consequence of the lack of coal, the Bennerley Furnaces were damped down in early August, resulting in 150 more men being out of work. The leaders of the Derbyshire Miners’ Union had collected on behalf of the men among tradespeople for a fund to support the families, though Union funds weren’t expected to last much longer. The Conservative Miners’ Association was in a stronger financial position however, and were expected to finance their members for several more weeks.

By the beginning of September 2500 a week had been given out at the South Street schoolrooms to children in the south district of the town. A similar scheme was now in operation at Chaucer Street schools for children outside that area and 1700 meals were donated. There were also notable examples of local charity by town tradesmen. For example Samuel Wood, grocer and baker of North Street, gave away large quantities of bread, while Bath Street fishmonger Moses Fulwood supplied half a ton of produce,

Most of the pit-heads in the district were being rifled by ‘gleaners’ whose families were running short of fuel.

The strike (or ‘Lock-out’ as some folk referred to it) had been caused by the coal-owners desire to employ miners only after a 15% (at least) reduction in wages. Three months later some pits had opened after the owners had agreed to pay the ‘old wages’; however there were still lots of employers, including the Mundy family (at Shipley) and the Cossall pits, who were not budging. Consequently community aid continued to be given. The Central Relief Fund gave out-of-work married men 1/6d in provisions while single men got half that amount. A free tea was provided to 800 local women who were afterwards provided with entertainment at the Town Hall. And a day or two later, 2000 children enjoyed a similar treat at the Town Hall and in Cotmanhay.

Seeing little prospect of the Cossall Colliery reopening any time soon, a couple of coal contractors arranged to retrieve their tools from the pit. They completed half their task and were returning to the surface riding in a tram along an inclined plane. However they picked up too much speed and when their ‘vehicle’ reached the end of the track it collided with an obstacle, tipping them both out violently. One passenger, Samuel Aldred of Essex Street, escaped relatively uninjured, but the other — young Elijah Evans of Taylor Street, son of Noah (a coalminer and ‘well-known musician‘) — was severely cut around the head. Both were taken by ambulance to the Ilkeston Cottage Hospital though only Elijah was kept there.

The first of the local collieries to be reopened was the Manners Colliery but almost immediately it experienced problems. Perhaps through lack of adequate maintenance during its closure, there was an explosion of gas there (the day after Elijah’s accident). Willoughby Cope of Chapel Street, was badly burned about the face, neck, arms and back, and joined Elijah at the Cottage Hospital.

By mid November 1893 the dispute was at an end.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

October 26th 1893: Edward appears at the Petty Sessions

The Vicar appeared at the head of a very distinguished deputation of 24 ‘Temperance Reformers’ before the Petty Sessions Bench. Behind and supporting him were the ministers of Holy Trinity, Hallam Fields, several Ilkeston chapels, Councillor Joseph Scattergood, and a group of leading town tradesmen. They were present to urge the magistrates “to exercise the greatest vigilance in dealing with the drunkenness and the use of obscene language so prevalent in the town”. They wanted any defendants accused of drunkenness to appear in person at court, as well as the severe prosecution of any publicans who allowed their patrons to become drunk. The granting of music licences to public houses ought to be more strict while the use of obscene language should be dealt with more harshly. The Bench agreed to do what it could to diminish the evils of drink and bad language which they all deplored.

The deputation (later known unkindly as ‘the Vigilance Committee‘) thanked the Bench and withdrew — subsequently to approach the police with a similar request. But this was not the end of the matter !!!

By the end of the year, two plain clothes policemen had visited several pubs in the town, had arrested four ‘drunkards’ and laid summonses against the landlords who had ‘allowed’ the drunkenness. Members of the Licensed Victuallers’ Association were outraged by this clampdown and were determined to oppose this victimisation !! A mass meeting in the Market Place was organised (thanks to the bell-man … no Spotted Ilson on the internet then of course), and at its head was coalminer Theophilus ‘Bob’ Gregory. He attacked the ‘Vigilance Committee‘ vehemently and included a personal verbal assault against many of the clergy involved. He was followed by William Holmes, formerly landlord of the Old Harrow Inn and recently convicted for striking a police officer, who recounted how he had been spied upon by the police !! And finally, amid ironical cheers, laughter and uncomplimentary epithets, brave Councillor Joseph Scattergood, member of the notorious Committee, mounted the platform and attempted to defend his position. He spoke for a few minutes but, perhaps somewhat intimidated by cries of “Chuck him off the platform” the Councillor made a strategic retreat. After a couple of hours of animated discussion, the culmination was the passing of a resolution condemning the actions of the authorities.

It was later understood that the ‘Vigilance Committee’ would hold a meeting to express its support of the police action, and defy any attempts at intimidation — either of the police, the magistrates or the committee’s members. And amid snow and buffeted by a keen wind, 300-400 people assembled in the Market Place to attend this ‘follow-up’ meeting, organised by the Temperance Association, on January 3rd 1894. They stood there for just over two hours. The first speaker was naturally Joseph Scattergood, followed by the Salvation Army Captain and then several of his ‘privates’ … none of them having any success in making themselves heard. Cheers, groans, shouts, laughter, jeers, altercations among the crowd, all combined to make the voices of the speakers impossible to be heard. That is until the anti-Temperance speakers took over the stage, they having some (but not complete) success in being heard. The meeting was brought to a conclusion by Theophilus Gregory (once more !) who shouted from the platform that he would sooner be a publican’s lackey than a teetotal ass.

And then, to add salt to the wounds of the Licensed Victuallers Association, on the following day, John Wheatley junior, landlord of the King’s Head in the Market Place, appeared at the Petty Sessions, accused of allowing drunkenness on his premises and of selling beer to a drunken person. The police, in the guise of two plain clothes constables, had been at John’s premises on two separate occasions in the previous December and swore that they had seen two obviously drunk customers served with more ale by either John’s wife or by John. Both the landlord and landlady disputed this, supported by the two ‘drunken’ customers and several other customers who had been at the inn. Their solicitor, paid for by the LVA, argued that the policemen had perhaps adopted a very unfair way of investigated the premises and had entrapped John by being in plain clothes. Perhaps they had an ulterior motive in securing a conviction and so enhancing their ‘reputation’; they had a strong prejudice and bias. They might even have colluded in presenting an agreed prosecution case. And who could determine whether someone was drunk or sober with any certainty ? The solicitor finally pleaded that the witnesses for the defence should be treated as credible as the police. However it was clear that, whatever the solicitor argued, it was not going to influence the magistrates who, as usual, were inclined to believe the P.Cs

Although the two cases were treated separately the court’s decisions were the same …. guilty of permitting drunkenness on his premises. However the magistrates didn’t think that a heavy penalty was necessary, and thus a fine of £1 in each case was imposed. And nor was John’s licence to be endorsed. The charges of selling drink to drunken customers were withdrawn by the prosecution. As the defence solicitor suggested, perhaps a crusade on ‘unrighteous principles’ was being conducted ?

The police clampdown continued. At the same time, Henry Belfield Clay, landord of the Mundy Arms, was caught in the same way, charged for the same offence, and received the same punishment. However there was a ‘not guilty’ verdict for Arthur Tinsley at the Sir John Warren. The plain clothes policemen visited quite a few pubs during those nights — a good job that they ordered ginger beer on quite a few occasions !!

—————————————————————————————————————————–

November 8th 1893; Edward welcomes St. John the Evangelist

A local newspaper described what attendees would see as they came to the new Nottingham Road church … “a massive stone wall divides the site from the roadway, where a temporary pathway has been made. Passing through the gateway, a sloping, curving walk carries the visitor past the nether regions where the heating apparatus is stored, up to the main entrance at the west end of the south aisle, where a fairly large porch serves as the ante-chamber to the sacred edifice itself. Proceeding inside one takes in at a glance the quiet beauty of the Early English style of architecture, on the lines of which the whole building is moulded. Nothing elaborate, nothing ornate obtrudes upon the gaze to destroy the sense of simple dignity which pervades the whole structure.

The nave is lofty, and well lighted by groups of clerestory windows running along each side; the walls resting upon gothic arches, supported by plain Doric columns.

The roof is carried by massive beams, terminating upon the upper walls, and intervening spaces are boarded over in panels.

At the west end stands a font of simple design, in front of the recess and upon the raised platform which forms the baptistry.

The west wall is pierced by three lofty, narrow windows, and the temporary walls at the opposite end, and between the arches separating the nave from the yet unbuilt north aisle are similarly treated, the former with three lights and the latter with one each. Another series of windows runs along the outside wall of the existing aisle.

The east end is appropiated to the purposes of the choir and chancel, and is divided from the main body of the church by a plain wooden screen, bearing along its upper ridge the text, in white letters on a red ground, “God manifest in the flesh” and “Behold the lamb of God”. The apex of the screen is surmounted with the symbol of the Christian faith. At one end of the screen, affixed to the wall, is a framed picture of the crucified Saviour.

top diagram:https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Basilica

bottom diagram: http://www.culturaltravelguide.com/what-is-a-gothic-cathedral

The pulpit is placed to the left hand side of the screen, and the lecturn on the opposite side, the small organ being nearer the centre of the screen. The alter is of the usual type with the customary ecclesiastical drapings. At the back is a gilt reredos of geometrical contour. The episcopal chair is placed to the left of the altar. The floor is of blocks of wood arranged in neat patterns, whilst up the nave and aisle pathways of red brick bordered with black, and down each side of the central pathway and along the walls of the aisle run the hot water pipes for the heating of the church. The heating apparatus is of the usual low pressure type and was supplied by Davy and Mansfield. The artificial lighting by gas is ample, a long line of burners running along the walls of the nave, and stately brackets lighting the aisle. The ventilation is secured by the opening of some of the clerestory windows. The church is seated with rush-bottom chairs. Besides the main entrances, entrance and egress can be obtained through the smaller doors at the east end of the aisle and at the north-west corner of the nave ( Belper and Alfreton Chronicle, Nov 17th 1893)

St. John the Evangelist Church in Nottingham Road was formally dedicated and opened for service by the Bishop of Southwell and attended by ‘a large and fashionable congregation‘, all seated on their new wooden chairs. The main entrance was close to Nottingham Road, at the west end of the aisle, with several other entrances at both ends. The carved wooden pulpit was the handiwork of the Rev. Rees. while ‘Miss Green‘ was responsible for supplying the bell, made by John Taylor & Co., bellmakers of Loughborough. (This was ‘Miss Green‘ the recently divorced ‘wife’ of Frederick Shaw who had adopted her maiden name of Adela Green since the divorce, and was living at Sough Closeses in the Larklands area).

—————————————————————————–

Obviously the Church of England was prospering in the ‘improving town of Ilkeston‘. In the last 45 years, up to 1893, the town had seen Christ Church built in the new parish of Cotmanhay carved out of the ‘unwieldy parish‘ of Ilkeston, the new church of Holy Trinity with a district allotted to it, and now this church of St. John with a new parish soon to be granted to it. However the man who had contributed so much to the formation of the new church — Sydney Robert Noel Rees — left Ilkeston at the end of the year when he accepted the living at Thorpe Arnold, Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire. He was replaced by the Rev. William Thomas Longman.

By November 1894 there was still a debt of £709 remaining on the St. John Church building … and as a consequence the new (8th) Duke of Devonshire and his wife arrived at Ilkeston for his first visit to the town, to open a three-day fund-raising bazaar at the Town Hall. The arrangements were in the hands of George W. Bridges, a celebrated bazaar decorator of King’s Lynn and Manchester, who had designed an Indian Palace inside the Town Hall. Entering the main hall, the visitor was faced by a scene of Oriental splendour … at the far end, an immense picture of brilliant, vivid colours representing the Ganges Valley, while the other end was dominated by representation of an Indian Palace. The side walls showed scenes through the arches of the palace, while all the stalls reflected luxurious eastern fashion. As if this weren’t enough, your eyes could be drawn towards the large case within which stood a large, inanimate but very life-like tiger with its prey in its mouth. All the stall-holders were dressed in the fashion of the Indian peninsula, their stall appropriately named after Indian provinces.

All the ‘great and good’ were present as the Vicar opened proceedings by recounting, once more, the history of the new church from the days when it was no more than a nascent idea in the mind of his predecessor, the Rev. Ebsworth. Other speakers followed, before the Duchess of Devonshire declared the bazaar open, was then thanked along with the Duke, who then rose to respond and make a speech — a rather lengthy one — before the spending began. Spending which totalled £270 of which £200 was the estimated surplus after expenses.

A pulpit screen and new organ, given by the Stanton Ironworks Company, were added at the beginning of 1897.

By the end of 1898 the Church’s debt had increased to £660 but subscriptions made shortly after reduced this to £515. By now the Rev. John Thomas Bell had arrived as Curate/priest-in-charge (about December 1897). The population of the district was increasing significantly while the church could only seat about 340 persons — not large enough for the expanding congregation. Time to clear off the debt and then turn to finishing off the building !! A north aisle needed to be added and the chancel wanted building on. A provision had been made in the plan for a spire but this would have to wait. Time for another bazaar !! And it came to pass that it was held on February 13th and 14th, 1899, when about £120 was raised

—————————————————————————————————————————–

December 28th 1894: And here is the Weather Report 1

Friday evening and into the early Saturday morning a gale-force wind tore through the town. Inhabitants awoke to streets strewn with slates, chimney pots and ridge tiles.

In the nave of St. Mary’s Church the Rev. Evans peered up to the ceiling and could see the sky outside — a portion of the roof was missing.

His ecclesiastical neighbour at the Independent manse in Pimlico had lost his chimney stack which fell through the roof, causing havoc but no harm to the inmates.

Also in Pimlico the recently-built Inglewood House of Charles Woolliscroft lost one of its stacks resulting in another wrecked roof.

The Nag’s Head and Old Harrow both lost pots and slates, as did several Bath Street shops.

At the Midland Town Station a large advertising hoarding was advertising no more.

Telegraphic services were disrupted … the town was cut off from its football results !!

And Shipley Wood lost several of its ‘inhabitants’, some of them very old indeed.

February 11th 1895: And here is the Weather Report 2

Like most of the area Ilkeston was suffering from the Great Frost of 1894-95, and this had resulted in considerable distress for the working population and those who relied upon it. This was calculated to be about 100 families in total as bricklayers, plasterers and associated labourers were out of employment. The Frost had also resulted in a burst boiler at the Euclid House residence (South Street) of Councillor George Haslam !!! … the boiler shattered to pieces, brickwork and cellar contents were damaged, but fortunately all residents were out at the time. However three-year-old Edward Halfpenny was far less fortunate as the Frost led indirectly to his death on February 21st. Because her tap had frozen up, his mother was forced to leave the house and visit another tap 50 yards away; when she returned Edward’s night-gown was on fire, and despite her frantic efforts and dressing of his burns, he died several hours later.

A very cold easterly flowed across the UK and most of Europe in February, and there were severe frosts with minimum of -13°c at Loughborough and -15°c being recorded at Chester. Heavy snow showers also persisted, with Yorkshire and Lincolnshire getting the brunt. South Shields was severely affected by 15 hours of continuous snowfall forcing the closure of the shipyard. Douglas on the Isle of Man recorded 20cm of snow. As the high pressure over Scandinavia moved over the UK there came a phenomenally cold spell with exceptionally low minimum temperatures of -20°c or less being regularly recorded. At Braemar on Feb 11th, a temperature of -27.2°c was recorded – the lowest ever UK minimum. Also on the 11th a temperature of -24°c at Buxton was recorded, -22.2°c at Rutland, and -12.7°c was the mean average temperature for Wakefield in Yorkshire between the 5th and the 14th. (Royal Meteorological Society)

The Vicar was in the small audience of the February meeting convened by the Mayor and attended by the Town Clerk, several councillors and most of the town’s clergy community. The attendees agreed to set up a Relief Fund, the first £30 being collected that evening. The rest of the town would now be canvassed for further subscriptions.

A Committee and then a sub-committtee were formed to receive donations and then to distribute those funds, granted in proportion to the needs of the applicants. By the beginning of March, subscriptions totalled £95 of which £63 had been distributed in relief.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Spring 1895: the Churchyard needs care and attention

Both of St. Mary’s graveyards were looking very forlorn. It was time for action !!! Unfortunatley there were no funds to finance a ‘spruce-up’. The Vicar therefore called a meeting at the Girls’ National School and …. you guessed it !!! …. a committee was formed, called imaginatively, the “Ilkeston Churchyard Improvement Committee“, to elicit subscriptions from willing donors.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

August 24th 1895: and another new church

“Through the munificence of the Stanton Ironworks Company”, Hallam Fields was to be furnished with “a handsome and commodious permanent Church”

The Company had erected a temporary iron Church in the district in 1880, along with a school and, more recently, a parsonage. Since the first church was built however the population of the area had increased markedly and it was recognised that a more substantial building was needed. St. Batholomew’s Church was thus designed to accommodate a congregation of 400-500 at an estimated cost of £2600. On a sunny Saturday afternoon of St. Bartholomew’s Day, its foundation stone was laid by George Crompton of Stanton Hall — he used a fine silver trowel with an ivory handle which had been presented to him by the workpeople of the firm. On the stone was inscribed the words “Ad dei gloriam” and stated that “the foundation stone of this church, erected by the Stanton Ironworks Company and their friends, was laid on August 24th, 1895 by George Crompton, chairman of the company”. A photograph of the occasion was taken by Seaman & Sons.

Designed by Percy Heylyn Currey, the church was to be of Leicestershire red brick with Coxbench stone dressings; the chosen builder was William Vincent Ireson of East Street (the same architect and builder who were chosen for St. John’s Church). There was to be a nave (64½ feet x 23 feet), aisles (64½ feet x 10½ feet) and a raised chancel (27½ feet x 23½ feet), with an organ chamber and vestries; the style would be early decorative. The seating was planned to be chairs, and the heating was by means of a hot water system, installed by the ironworks company. It was expected to be finished by the Easter of 1896. It should be noted that this ‘first-edtion’ church had no tower — that was added ten years later.

By the beginning of May it was almost complete. A bazaar was then arranged, hopefully to raise £60 for the “East Window fund”; this ‘Congregation’ window was of seven lights. The font was ‘the gift of the children’. The Mayoress was on hand to conduct the necessary opening ceremony, along with her husband, the Rev Evans and several members of the Crompton family.

Two photos of St. Bartholomew’s Church in Hallam Fields taken by Jim Beardsley about 1975

The one below taken from Hallam Fields Road

The one on the right taken from Crompton Road

On May 6th 1896 a Dedication Service was held to herald the arrival of St. Batholomew’s Church, which joined the schoolhouse, parsonage and temporary church, all previously provided by the Stanton Iron Works of the Crompton family.

The Church Army Mission re-erected 1897 (Ilkeston Reference Library)

The original iron church (above), erected in 1880, was now taken down and transported to the junction of Station Road and Alvenor Street, where it was rebuilt at the very end of 1896 and into 1897, on a site granted by the Duke of Rutland at a nominal rent. It was presented to the Church Army Mission (instituted in Ilkeston on March 4th, 1892) and which was worshipping just off Station Road in Bethel Street, in temporary accomodation there. The cost of this removal exercise was £160. In effect it had been gifted by the Stanton Iroworks Company to the Vicar of St. Mary’s Church in whose parish it now stood — it wasn’t rented by him but was now owned by him for the purpose of extending mission work and the Church of England.

The Mission chapel was opened on February 2nd, 1897 by the Bishop of Derby … and with a debt of £120 !! Captain J. Bell was in charge, and it was in September 1898 that Vicar Evans attended the Mission to say farewell to the Captain. He was becoming the van missionary in the Salisbury diocese. Captain Lancaster was replacing him.

By April 1899 the Mission debt was £93 and needed to be reduced. Thus, time for a fund-raising “sale of work” — sweet sales, artwork, refreshment stalls, attracted a ‘moderate attendance’. And Captain Lancaster was moving on, to be replaced by Captain Jones.

By December 1900 the debt stood at £95.

Post script: the Church Army Brass Band (courtesy of John Wood)

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Edward puts pen to paper once more: May 1896

Edward was cross … very cross. He had read in the local press that the School Board had been approached by a “travelling van man“, asking to use the old British School premises in Bath Street for his religious services every morning and evening on Sunday. And that this request had been granted. The Board had considered that these were ‘Church of England services‘ and were conducted with ‘the decorum of the Church of England‘. The ‘van man’ was a member of the Church of England Protestant Mission recently established in Ilkeston, but to the Rev. Edward he was simply an itinerant ‘missionary, a fanatical orator of a Puritan faction’. His name was David Steventon Hyslop — and according to Edward, he was not a parishioner nor in any way connected with the town. David had arrived at Ilkeston a few months earlier as part of the “Anne Askew” van of the Protestant Mission and began to preach a nightly sermon. (Anne Askew was a sixteenth century Protestant martyr). However since his arrival he had cut his ties with the ‘van’ and had setteled in the town where he now conducted regular services. (His son David junior was born in Ilkeston later in the year). The Vicar felt it was his duty to write to the Board (which he did), pointing all this out and adding that these services had not been authorised by the Bishop of the diocese or by himself. Did he then try to overwhelm the Board members by referring to the Canon Law 1603, citing when and how ratepayers property might be used ? The Vicar could understand a Nonconformist of definite principles being allowed the use of the premises, “but when a person poses under the guise of the Church of England principles, and refuses to be subservient to such principles” then the Board should refuse his request. And he added that he had the support of all the clergy of the town.

All of this came at a time of some controversy in the town’s religious atmosphere — when the Rev. Binney of Holy Trinity Church and, to a lesser extent, the Rev. Evans himself, were caught up in charges of ‘excessive and extreme ritualism‘ at their churches.

At the May meeting of the School Board, member George Knott declared that he had visited one of the services complained about and had found it a most decorous Church of England service — nothing for the Vicar to worry about !! And other members offered the same view. To them it seemed that Vicar Edward was perhaps concerned about these services as they did not include the ‘paraphernalia’ and ‘ritual’ found at St. Mary’s and St. John’s. Board Chairman George Dean once more found himself in a minority of one. His view was that school premises should not be hired out for any purpose other than an educational one. When he tried to put a motion to the meeting that they should require the ‘van man’ to stop using their premises, there was no seconder !! The matter then dropped.

The Derby Daily Telegraph didn’t drop it though !! The newspaper was on the scent of Vicar Edward who it called “a red hot Ritualist“. And Edward was on the scent David Hyslop. The latter had secured possession of the old Temperance Hall in Lower Granby Street in order to hold week-night services; he had come to an agreement with the Hall’s agent, William Briggs, to rent the lower part of the Hall — the upper hall had been let to the Rev. Alfred Jackson for his ‘Ilkeston Town Mission’. But Edward was having none of this !! Behind David’s back the Vicar approached William Briggs in an effort to pursuade him to revoke the agreement but the agent refused. Undeterred the Vicar then contacted the owner of the Hall who was persuaded to let it to the Church for a year, over the head of the ‘fanatical Puritan orator‘. David was thus denied use of the premises. Game, set and match to Vicar Edward ??

—————————————————————————————————————————–

An Anniversary Garden Party … in the Town Hall !! June 16th, 1897

Edward entertained over 200 visitors, mainly church and Sunday School workers, as he celebrated with them, the tenth anniversary of his arrival in Ilkeston. The wet weather meant that the planned garden party could not be held on the Vicarage lawn: everyone adjourned to the Town Hall.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Spring 1898: Park Cemetery, a source of conflict

While Edward was always willing to welcome new Anglican churches into the district, and to be present at their dedication, there were other new arrivals he was less willing to accept.

In 1892 the Cemetery Committee of the Town Council invited the Bishop of Southwell to join with resident minsters in a dedicatory service of a new cemetery — Park Cemetery at the end of Park Avenue. However the Council had decided not to consecrate any part of this new cemetery so that, in a letter dated July 19th, 1892, because of this decision, the Bishop declined to take part in this service. Just over a month after the Bishop’s refusal — on Wednesday August 31st — the new cemetery was publicly dedicated, though the occasion was boycotted by the Anglican ‘churchmen’ of the town, including the Church members of the Town Council and Edward, of course. “However, nobody seemed one penny the worse by reason of their absence” (Derby Daily Telegraph).

Several nonconformist clery were present however — Thomas Roberts (Wesleyan), James Bainton (Congregationalist), William Evans (United Methodist Free Church). J. Hardy (Primitive Methodist). It was left to Councillor Joseph Scattergood to declare the cemetery open to interments, and after a final hymn the proceedings terminated.

However, by 1898, it appeared that Park Cemetery was still proving to be a contentious issue between the Council and the town’s vicar. In April of that year Edward wrote to the Council indicating that, from now on, the clergy would no longer attend Sunday funerals at the publc cemetery and asked that Sunday funerals be discontinued. The request was promptly declined and Councillor Edwin Trueman, himself a Churchman, applauded and supported this decision, arguing that the clergy should carefully consider the interests of the ‘working classes’ for whom Sunday was the most convenient day.

February 11th, 1900: St. Mary’s gets a new window

On this Sunday the Rev. Edward was present in church before a crowded congregation to witness the unveiling of a memorial window to the late Janetta Manners, Duchess of Rutland, by Alfred Edward Miller Mundy and situated in the chantry.

Janetta Manners (nee Hughan) 1836 – 1899

Janetta had last been in Ilkeston at the opening of the Lord Haddon Coffee House and Restaurant in December 1898, and when once a visitor to the church, she had remarked on the lack of such memorials as the one which was now to celebrate her … and an addition to the one, also in the chantry, erected some years previously by Edward, in memory of his parents.

All the work towards the window, at a cost of about £80, was undertaken by Messrs. Lavers and Westlake of Bloomsbury. It was the central one of three on the north side, its three main lights representing, left to right, the Incarnation, the Ascension and the Epiphany. Under the first light appeared the words “Emmanuel, God with us“; under the second, “He ascended into Heaven“; under the third, “They presented unto Him gifts” — and each one surmounted by an ornamental 14thC canopy. Small lights at the top were filled in with representations of the dove, angels and a coronet. The inscription at the foot of the window read “ To the glory of God and in memory of Janetta, Duchess of Rutland, this window is dedicated by tenants, parishoners, and friends 1899. R.I.P.“

Seven months later, 0n September 14th, and transported by a special train from their home at Longshawe, the Duke of Rutland and his daughters, Katharine, Victoria and Elizabeth Manners, visited Ilkeston. They were initially entertained by Edward at the Vicarage before being escorted to the Chucrh to inspect the commemorative window. Apparently, all were pleased with what they saw.

May 1900: Derby and Derbyshire Adult Deaf Mission

Edward was present to reside over a meeting at the Church Institute to discuss the establishment of an Adult Deaf Mission at Ilkeston for the whole of the Erewash Valley. It was successfully proposed to hold monthly meetings at Ilkeston. Fred Harcourt Roe was on hand to ‘interpret’. (He was the son of the Headmaster of the Royal Institute for the Deaf and Dumb at FRiar Gate, Derby). “An excellent tea had already been provided for the deaf mutes at the Lord Haddon coffee tavern“.

January 26th 1901: Imprisonment, death and destruction

Tommy Quinn had just been sentenced to spend another month at Derby jail, an event which coincided with a severe gale throughout England … including Ilkeston. In recognition of the death of Queen Victoria the flag on the tower of St. Mary’s Church was being flown at half-mast … but not for much longer, as the violent wind caused the flagpole to crash to the ground. As it fell it knocked off one of the heavy stone pinnacles which crashed into the roof and caused considerable damage. Other flags, on the Town Hall and Rutland Hotel, were torn to shreds, while the plate-glass window of Boots’ Fancy shop in Bath Street was smashed by the errant window blind of its neighbour.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

And so on, to the bell-ringers