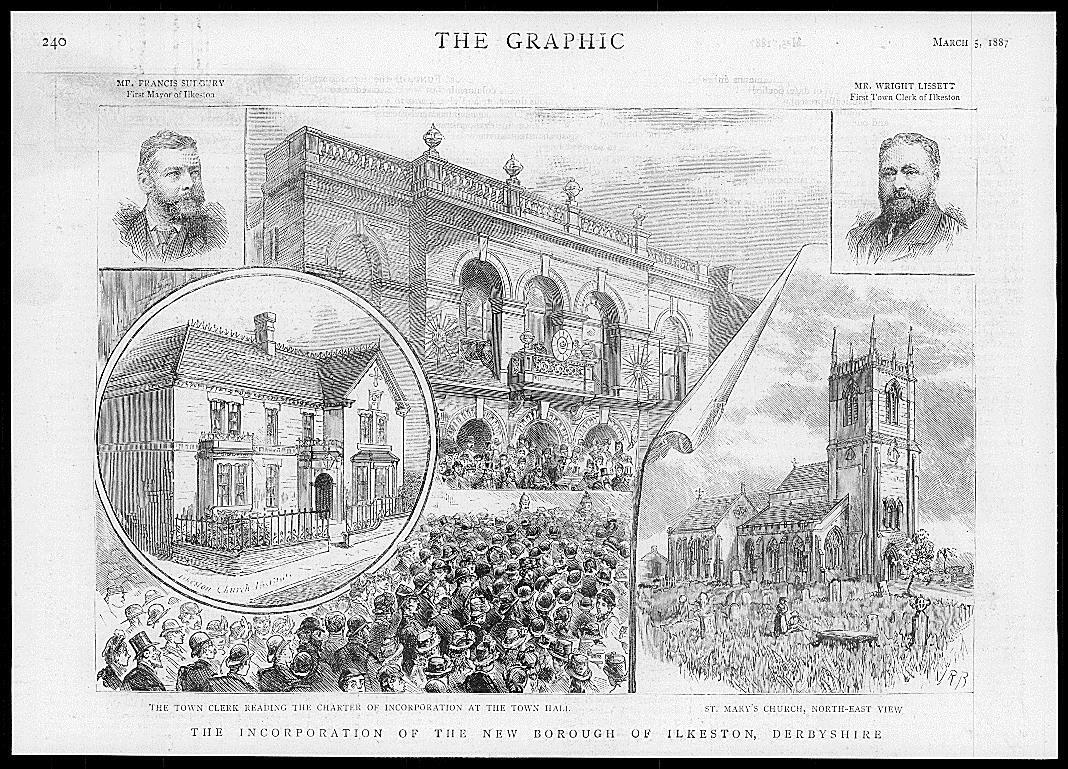

Scene: Ilkeston incorporated.

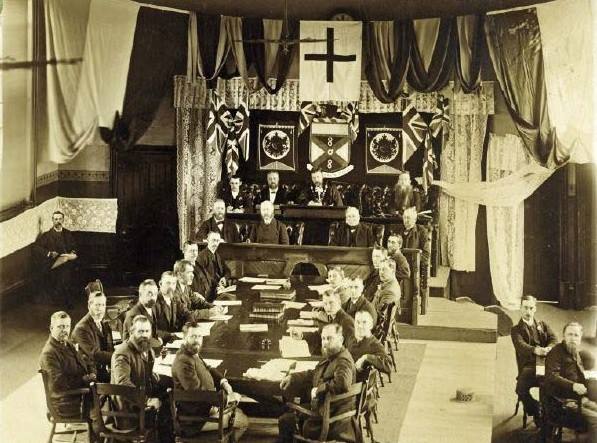

And what has the Local Board ever done for us? …. Well, here is a photo of the last Local Board, as it appeared in 1887 (though it had been elected in 1886 —sort of !!) The very last ‘Local Board election‘ took place at the end of March 1887, but as the Board was only due to survive for a few more weeks, it wasn’t felt necessary for the six retiring members to face re-election. So no contest was staged.

When the Local Board was formed its first year’s income was £507. In its last year that figure had increased to £15,463.

But why wasn’t the Local Board going to survive ? This is explained below.

Seated are front row left to right: Charles Haslam, William Wade, William Sudbury, Francis Sudbury, William Tatham and Isaac Attenborough and unknown. Second row left to right: Walter Tatham, Charles Maltby, Frederick Beardsley, Samuel Richards, Samuel Robinson, George Haslam, unknown, Wright Lissett and unknown. Behind second row left to right: William Fletcher, Edmund Tatham, Joseph Shorthose, Edwin Trueman and three unknowns.

The retiring Board members are shown in red — and as the names of two (William Smith and John Carrier) are missing from the above list, they should be among the ‘unknowns’.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Local Board makes way for the Town Council

At the beginning of October, 1885, the question of applying for a Charter of Incorporation for the town was brought up by the clerk to the Local Board, Wright Lissett. Because there was a possibility of expense, it was decided that the ratepayers of Ilkeston needed to be consulted. When in doubt, circulate a petition — which was what was decided.

The Public Meeting

On January 18th, 1886, following a unanimous resolution by the Local Board, its chairman Francis Sudbury convened a public meeting of the town’s householders at the Town Hall “for the purpose of considering the provisions of the Municipal Corporation Act 1882 as compared with those of the Public Health Act 1875, and deciding whether it is desirable to petition the Queen for a charter of incorporation”.

He prefaced the proceedings of the meeting with the observation that the members of the Board were not there as ‘special pleaders’. Who was he trying to fool?

Wright Lissett, clerk to the Local Board, then set out to a rather sparse audience of town ratepayers the differences in the provisions of the two Acts.

The 1882 Act demanded a more regular and systematic election of representatives, with no person being nominated who had not been consulted. The same act introduced a ‘fairer’ system of voting; “all ratepayers stood on the same level. No person could vote as an owner as well as an occupier; but all persons whose names appeared on the burgess list had one vote – whether man or woman”. The Clerk also explained differences in the auditing of accounts, and in the position, power and privileges of Board members compared with those of a Corporation.

And none of the existing Board’s powers would be lost but new ones would be gained.

A Town Council would be no more expensive than the present Local Board. However the costs of incorporation would depend upon how much opposition there was and how organised it was. No part of any adjoining parish would be asked to be included in the charter so that he could foresee no ‘outside opposition’. Perfect unanimity would incur trifling expense. Ilkeston was now a large and growing town, the most important place in the Erewash Valley, the centre of its own Parliamentary district to which it gave its name, and incorporation would enhance its position in the commercial and financial world. Successful businessmen would be encouraged to remain in the town and not seek greater success elsewhere as was now the case. They would give ‘higher tone’ to the town and others might thus be drawn in. This would produce a multiplier effect of an improved and better class of housing, more work for builders, labourers, artisans, females, more manufacturers would be sucked in, property values and rates income would increase, more gas and water would be used, shops would grow in size to compete with those in Derby and Nottingham, population would grow, and the process would then regenerate itself. (Applause.)

And what were the chances of the Privy Council granting a charter?

In size Ilkeston was the second town in Derbyshire with excellent railway accommodation, numerous factories, collieries and other works, and the Local Board owned the gasworks, waterworks and its town offices. All points which should weigh well with the Privy Council.

With just two dissentients, (Urius Griffiths being one of them), the motion was carried by the meeting.

Charles Dickens said he “awoke one morning to find himself famous”, but what could the feeling of that literary genius have been compared with those of pride,honour and fame, that will agitate the breast of the gentleman, whoever and wherever he is, who will some day in the near future, awake to a glorious knowledge of the fact that he is “Mayor of Ilkeston”. (Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald; Jan 30th 1886)

The Petition

The petition to consult Ilkeston’s ratepayers was got up and circulated around the town. I have tried to add extra detail to identify what was being described, though there are a few gaps and I may, of course, made mistakes.

The Petition listed all the attractions and strengths of Ilkeston ….

It is an important commercial centre.

It contains two banks, (the Nottingham Joint Stock Bank in the Market Place but soon to move to Bath Street, and Samuel Smith & Co Bank in Bath Street)

14 large and important lace and hosiery manufacturing mills (besides two others within 100 yards of the boundary), (Ashwell, Wells & Co. of Abbey Street; William Ball & Son of Albion Place; William Beardsley & Sons of Cotmanhay; Henry Carrier & Co. of Station Road; Henry Carrier & Sons of Bath Street; Samuel Fletcher & Sons of Wood Street; Frederick William Goddard of Market Street; William Hewitt of Heanor Road; George Maltby of Station Road; Pratt, Hurst & Co. of Lower Granby Street; Amos Tatham & Son of Belper Street; Tatham Brothers of Kensington; Charles and Francis Sudbury of Market Street; plus A.N. Other ?… and including, over the border, Thomas Birley and Frederick Draper, both in Middleton Street, Cossall.)

five collieries (as well as seven others in the immediate vicinity, where a great number of the inhabitants of Ilkeston are employed), (Ilkeston Colliery Co. Ltd. of Derby Road; Manners Colliery Co.; Rutland Colliery; Peacock Colliery; Butterley Co. Granby &c of Cotmanhay Road; and in the vicinity, Cossall Colliery Co. Ltd; Shipley Colliery of Miller Mundy; Stanton Colliery; West Hallam Coal and Iron Co.; and four others?)

two extensive iron smelting furnaces (and four similar works within 100 yards of the boundary), (including Erewash Valley Iron Furnaces at Gallows Inn; Stanton Iron Works Co.; West Hallam, Coal & Iron Co.)

one boiler and engineering works, (John Whitehouse of Rutland Street)

one foundry, (Rutland Works in Queen Street)

seven brickworks, (Beardsley & Pounder of Rutland Wharf and Gallow Inn; Joseph Horridge of Cotmanhay Road; Thomas Horridge of Gallows Inn; Manners Colliery Co. of Heanor Road; Oakwell Colliery Co. of Derby Road; Samuel Shaw of Chapel Street; Henry Hobson of Hallam Fields? )

besides numerous wholesale and retail establishments, carrying on a large trade.

It has four churches, (St. Mary’s in the Market Place; Christ Church at Cotmanhay; Holy Trinity Church at Granby Street; St. Batholomew’s Church at Hallam Fields)

17 chapels, (Congregational Chapel in Pimlico; Congregational Mission Room at Nottingham Road; Baptist Chapel in Queen Street; Old Baptist Chapel in South Street; Wesleyan Chapel in Bath Street and at Gallows Inn; Primitive Methodist Chapel in Bath Street, at Nottingham Road and at Cotmanhay; Methodist Free Chapel in South Street and at Awsworth Road; Methodist New Connexion in Market Street; Unitarian Chapel in High Street; New Testament Disciples in Lower Granby Street and at Cotmanhay; Our Lady of St. Thomas of Hereford Catholic Church at Regent Street; St. Mary’s Mission Room at Nottingham Road)

a Mechanics Institution with 140 members, and a Church Institute with 170 members, the latter having a handsome and commodious building. Two weekly newspapers are printed in Ilkeston, and there are the elements of a growing and populous town, which fit it for and require the best form of municiapl government.

By the end of March it had 1500 signatures attached to it. It was then presented to ‘her Majesty in Council’ to be considered by a committee of the Lords of the Privy Council.

However before a decision had been made by the Council, there was a last election for the Local Board. As usual six members had ‘retired’leading to this election in early April … Francis Sudbury, Edmund Tatham, Frederick Beardsley, Charles Haslam, Charles Maltby and Samuel Robinson were elected.

On June 30th 1886 a public inquiry on the proposal of Incorporation was held at the Town Hall — the proposal being opposed by the Stanton Ironworks Company, an opposition which was immediately withdrawn at the beginning of the meeting. After this, Wright Lissett, clerk to the Local Board, set out the case for incorporation which included a list of the recent achievements of the Board and little else. The inquiry then concluded.

On July 17th 1886 the Local Board heard that its petition had been successful. There was to be a Town Council of six Aldermen and 18 Councillors, The town was to be divided into three wards — North, Central and South — and the first elections were scheduled for next November.

Incorporation Day, February 15th 1887

By the end of 1886, the Local Board was still waiting for the Charter of Incorporation to reach the town. It was now expected by the end of January 1887 but arrived a couple of weeks early. Thus, on Tuesday, February 15th there was a public reading of the charter (dated January 31st) in the Market Place. At this meeting the good people of Ilkeston were to be informed that they now had the right and duty to elect a Mayor, Aldermen and Councillors who would then administer their town. These elected gentlemen would raise money, via the property “rates”, to pay for its day-to day expenses as well as providing income for capital improvements for the town. In this way Ilkeston would become wholly responsible for nearly all aspects of its existence — Finance and the Fire Brigade, Gas and General Works, Highways and Health, Roads and Recreation Areas,Waste and Water, Street Lighting and Markets — everything except for Police and Secondary Education. All for the Borough population of just over 14,000 on an initial annual budget of just over £18,000.

The townspeople had felt it necessary to celebrate this momentous event with associated pageantry, illuminations and decorations. Thus, processions, decorations, massed singing of hymns, dinners, balls, illuminations … had all been meticulously plan ned days before. William Gadsby, conductor of the Ilkeston Harmonic Society (and domestic gardener and Parish Clerk at West Hallam) was in charge of the singing. So on the Sunday before the ‘great day’ he had visited every Sunday School in the town to listen to rehearsals.

The day itself was a public holiday. Lace and hosiery factories and collieries closed, shops were decorated, schoolchildren had a day off, and bunting, flags and evergreens were everywhere. The town assumed “a gorgeous and brilliant appearance”. In the morning trains arrived at both town stations, bringing in hundreds of visitors to mingle with the celebrating townspeople. William Barnes, butcher of South Street, reminded them all that “if you want a good Corporation eat Barnes’s beef”.

Weather Report: The sky wore “a dismal leaden hue, but the aqueous element did not assert its superiority over human arrangements”

Thousands of Sunday School scholars marched from Hallam Fields headed by the Ilkeston Brass Band. Similar numbers paraded from Cotmanhay, led by the Cossall Colliery Band. In total 5000 children marched towards the Market Place, each wearing a medal (donated courtesy of F.W. Goddard & Sons of Market Street, and bearing the inscription on one side ‘Ilkeston Incorporated, February 15th, 1887’, and on the other “Queen Victoria Jubilee Year 1887”). Many carried banners and small flags.

And while the youngsters were marching, the members of the old Local Board and Wright Lissett, “one of the chief heroes of the day” — about to be superseded by the Corporation — rode around the town in a large wagonette.

Afternoon came and as the bells of St. Mary’s Church rang out, Ilkeston Prize Band led into the square the first group of marching children. Outside the Town Hall a temporary platform, draped in blue and red stripes, afforded the Local Board members and invited dignitaries a prime view of festivities while the other sides of the Market Place provided a place for the brass bands. On the balcony, William Gadsby took up his position while below Francis Sudbury, chairman of the Local Board addressed the crowd; he made a few remarks and then read out the Charter of Incorporation. Ilkeston was now a borough !! And all this in front of the Market Place filled with what was estimated to be a crowd of 14,000 persons.

Songs were sung, hymns played, prayers prayed, speeches made, flags waved, Queen saved and cheers raised.

Every child left with an orange and a bun (the latter made by Solomon Beardsley, baker of Bath Street) and after dark the streets were thronged with meandering inhabitants taking in the “vividly brilliant” illuminations — “the Town Hall was a gorgeous mass of flame”, the work of Frederick Chilton Humphries, manager of the gas works, who had organised 7000 jets of gas to be employed.

And it was an excuse for a lot of eating and a very big drink. There was a evening dinner at the Town Hall, given by the new Mayor — mock turtle soup, fish, quarter lamb, saddle mutton, sirloin beef, turkey and tongue, jelly and blanc-mange, pheasants, wild ducks and plum puddings. And across the Market Place, at St. Mary’s National Schools, the head teachers (William Frost and Mary Elizabeth Baker) gave an evening dance which extended into the next day. Members of the old Local Board now decamped from their meal at the Town Hall and joined in the festivities at the National Schools, innervated and exhilarated by the food and drink, and by the significance of the occasion.

The Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald observed that ‘several very excellent photographs of the proceedings were taken by a Chesterfield artist’, photographer Alfred Seaman, who is shortly to open a studio in Ilkeston. The same newspaper proudly boasted that “Mr. Seaman was the only photographer who was successful in obtaining good negatives, and his photographs are therefore unique”.

“Mr. Francis Sudbury, the first Mayor-elect briefly addressed the crowd from a platform in front of the Town Hall. Then followed the reading of the Charter which confers upon Ilkestonians for all time the rights and privileges of municipal government “. (Trueman and Marston)

Commenting on the prospects for the town in its editorial section the Nottinghamshire Guardian …..

“From an architectural point of view (Ilkeston) is not, unfortunately, a delightful place and the aesthetic surroundings of the town leave much to be desired. But under the new Corporation all these will, no doubt, in process of time be improved and Ilkeston may even yet take its place amongst the handsomest and best regulated boroughs in the United Kingdom…… Under a Local Board the ratepayers have not the same control over their own affairs, nor such good opportunities of developing the local resources and improving the place”.

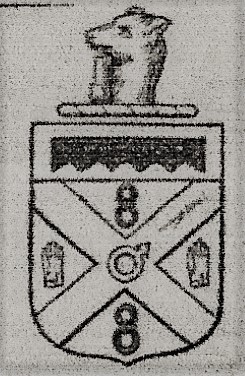

One last task remained … the provision of a Borough Coat-of arms. The outgoing Local Board decided that it fell to their members to design such a badge for the incoming full-blown Corporation. And the Derby Daily Telegraph (April 20th 1887) was mischievous and malicious in its criticism of this decison; “the distinctions in heraldry are so fine, and the etiquette so peculiar, that only a very learned person skilled in that branch of science ought to hazard even and opinion”. The old Board chose emblems to include which it felt best represented the growing town. A sketch was prepared and sent off to the College of Arms for approval, but soon came back a reply that the proposed design was totally unsuitable and contrary to heraldry. “But with a boldness which has perhaps never been equalled in the history of heraldry, the Ilkeston Local Board entirely dispute this allegation, and have asked for the return of the sketch, in order to make some alterations”. The newspaper concluded with its advice that “the Borough of Ilkeston would have done well to leave the matter unreservedly in the hands of the Heralds”

The last meeting of the old Local Board was on May 3rd, 1887 — the day after the election for the members of the new Town Council, the first meeting of which took place from noon on May 9th. Thus, farewell to the Local Board as it passed into history.

R.I.P.

Formed at a time of parochial division and discord it ended its days in an atmosphere of happy harmony and hope.

May 2nd 1887: Election time

Adeline summarises the town at this time (i.e.the 1930s): “Ilkeston of today, with 33,000 inhabitants, its up-to-date churches and chapels, its spacious schools, a Town Hall with a Mayor*, Aldermen, Councillors and officials, its excellent drainage system, and pure water supply. Motor cars and buses, speeding through the streets, well-lighted thoroughfares and brilliantly lit shops.

“All this is very different from the Ilkeston of the early fifties of last century”.

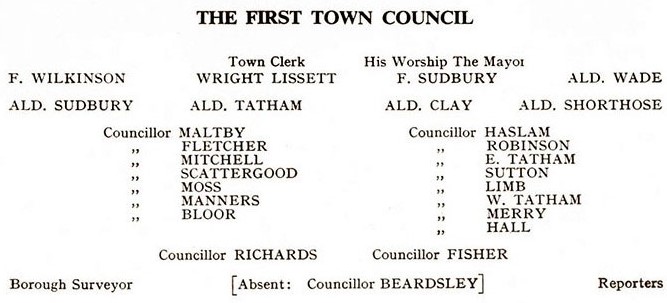

May 2nd, 1887 was the date when elections for the first Town Council took place. The new borough was divided into three wards — North, South and Central — each with the power to send to the Council six elected representatives. This Council would then elect six Aldermen.

The Conservative and Liberal candidates decided together that the contest would not be fought on ‘political party grounds’ …. there would be a friendly alliance. However when the results were known they were a surprise to all but especially to the Liberals. Expecting a Liberal majority in a predominantly Liberal town, that party discovered that they had exactly the same number of elected councillors as the Conservatives. They felt ‘dished‘ and vowed that in future there would be no alliance — strictly party lines would rule !!

The Nottingham Journal (May 9th) theorised that the election was “so colourless and uninteresting to the voters that they did not think it worth while to vote their whole strength upon it. The people of Ilkeston are enthusiatic enough when there is something to fight for, but when there is no principle in the balance they do not think it worth their while to interest themselves very much about it “.

It should also be noted that the so-called ‘Working Men’s candidates’ — like Richard Riley (Central Ward) and Benjamin Howard (South Ward) — fared very badly: both were bottom of their respective polls.

At the first Council meeting on May 9th all 18 members were present. One of their first tasks was to elect six Alderman. Voting thus took place and Francis Sudbury, Joseph Shorthose, William Tatham, William Sudbury, William Wade and Henry Clay were elected. This caused vacancies within the Council which now had to be filled. Thus further council elections in all three wards were planned. These took place on May 23rd and Samuel Robinson, John Lowe Moss, Samuel Richards and Edwin Hall were elected to fill the vacant seats.

Mentioned at the top of this page, Francis Sudbury was Ilkeston’s first mayor. Some Nottingham wit had previously asked if the string of pork sausages hanging in the Market Place shop window of his nephew (and butcher) Arthur William Sudbury, was the Mayor’s new chain of office.

On May 12th, after being introduced to the Bench at the first Ilkeston Petty Sessions since his election, Francis was sworn in and took his seat on that Bench.

This was especially pleasing to two old offenders Frederick Brown and John Daykin, who then appeared before the newly installed magistrate at the Petty Sessions… charged with ‘drunk and riotous behaviour’ and ‘sleeping out’ (respectively). As ‘an act of clemency‘ both prisoners were discharged.

And in the following month, another act of generosity by Francis ….

“The Mayoral chain which (Francis) Sudbury has presented to the town of Ilkeston is a beautiful specimen of the jewellers’ art, and was entrusted to Mr. John J Perry, of Angel-row, Nottingham, to procure.

“The chain, which is of 14 carat gold, is a succession of Roman shields linked together, each shield being surmounted with a coronet. On the large centre link, to which the badge is attached, is a richly-enamelled monogram of the donor, ‘F.S.’ On each side of the link is a beautiful raised cross-bar in front of a civic mace, each one being surmounted with a Royal crown. Hanging from the centre link is the badge. This is the most striking portion of the whole piece, and consists principally of 18 carat gold, on which is enamelled the Town Arms.

“Although the maker was confined to the somewhat sombre colours supplied by the Heralds Office, they form a striking contrast.

“Around the shield is a piece of raised gold work, composed of laurel and oak leaves, and on the bottom in bright enamel the motto ‘Labor Omnia vincit’. On the reverse side of the badge is the following inscription:– ‘Presented to the borough of Ilkeston by Francis Sudbury, first mayor, 1887, Jubilee Year of her Majesty Queen Victoria’.

“The gift has cost £300”. (NEP June 1887)

The photo below was taken on Tuesday June 7th 1887, and marked the first time that the Mayor and Town Clerk appeared at a meeting in their official robes. On the previous Sunday and in a departure from the custom, the Mayor, Town Clerk, Aldermen and Councillors had marched from the Town Hall to the Congregational Chapel in Pimlico (and not the Parish Church) to attend divine service. The police were on hand to keep the route clear.

By May 11th the new Town Council had decided upon a design (left). At the top, a leopard’s head holding a safety lamp in its mouth; the head had heraldic reference to the Cantilupe family of the town while the lamp signified one of Ilkeston’s major industry.

Beneath was the arms of St. Andrew’s Cross, between which were hanks of cotton and silk, and gloves, again indicating local trades, as was the band of lace above the shield.

At the intersection of the cross was the sign of Mars denoting yet another local trade of iron.

The motto was to be Labor omnia vincit (Work conquers all) though it hadn’t been decided how to include this — probably in a scroll under the arms

At the end of September 1887, Mayor Sudbury was in ebullient mood. The Duke of Devonshire, Lord Lieutenant of the county, had just recommended him for appointment as a county magistrate (a position he was awarded in the following month). Speaking at the town’s Agricultural Show dinner, Francis hoped that Ilkeston would extend in size, health, wealth, beauty. cleanliness and intelligence — that it would become a bright and shining light to the surrounding district, and a town of which they might all be proud.

However the Nottingham Daily Express was not so optimistic — “few will live to see such a delightful transformation effected in a town so thoroughly destitute of attractions, either natural or artificial” The Mayor could be forgiven for sounding so ‘up-beat’ however — his speech was a post-prandial one, and of course the usual discount must be allowed.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

At this point we will leave the new Ilkeston Town Council to get on with its work … and we will come back to it eventually to see how it progressed in the first 10 years or so of its existence, up to the close of the Victorian era. (You can, of course, immediately choose to skip to find out how the new Council progressed with its work).

——————————————————————————————————————————-

And now … Onwards, upwards and round the corner