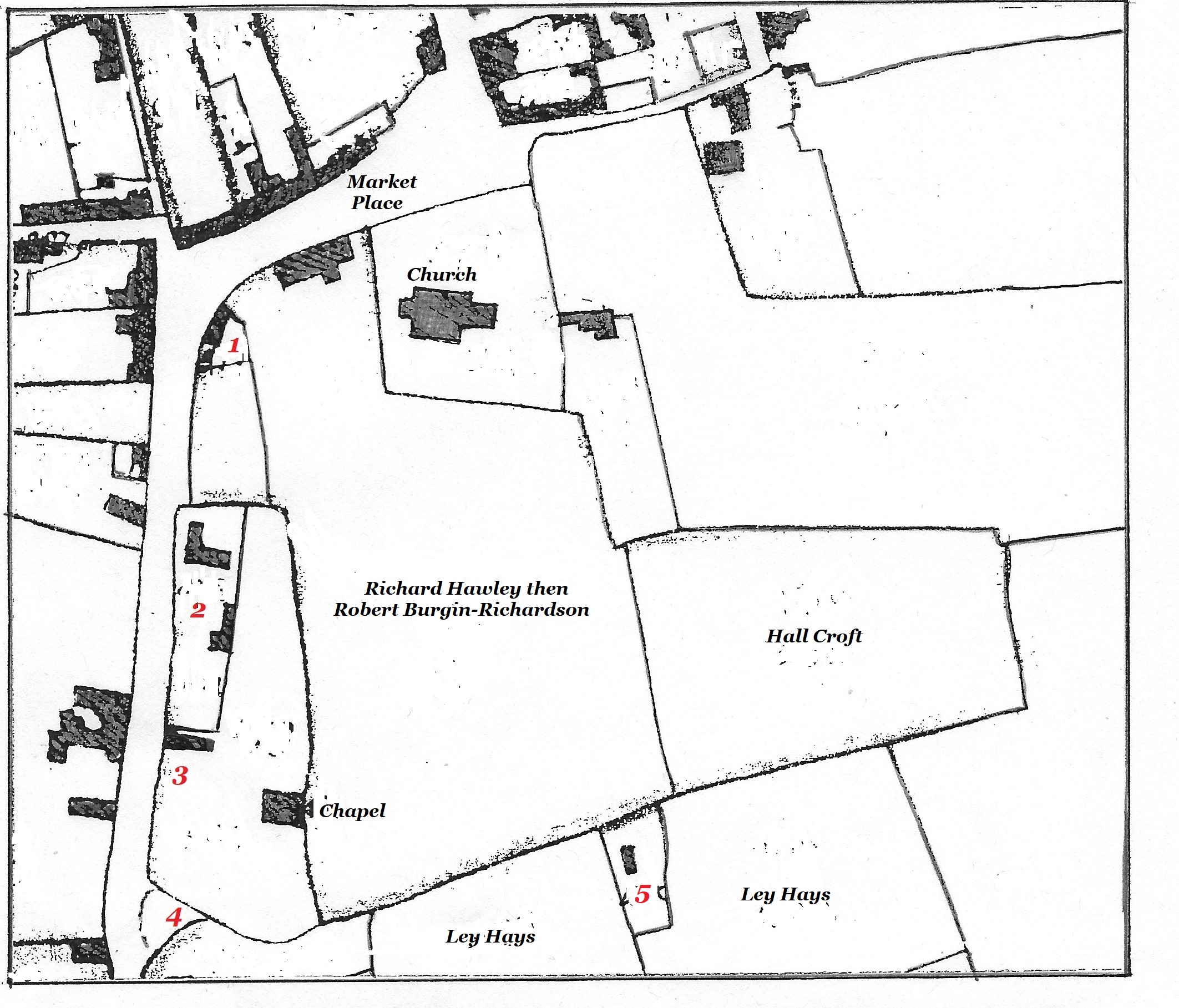

Ilkeston Market Place area about 1800

The above is a sketch made from William Gauntley’s maps 1795-1798, showing this part of the town at the end of the eighteenth century.

Notice how the Market Place in confined to what we today might call the Lower Market Place — the Upper Market Place, to the west of the Church, was then the homesteads of private individuals. And notice how sparse and scattered are the houses.

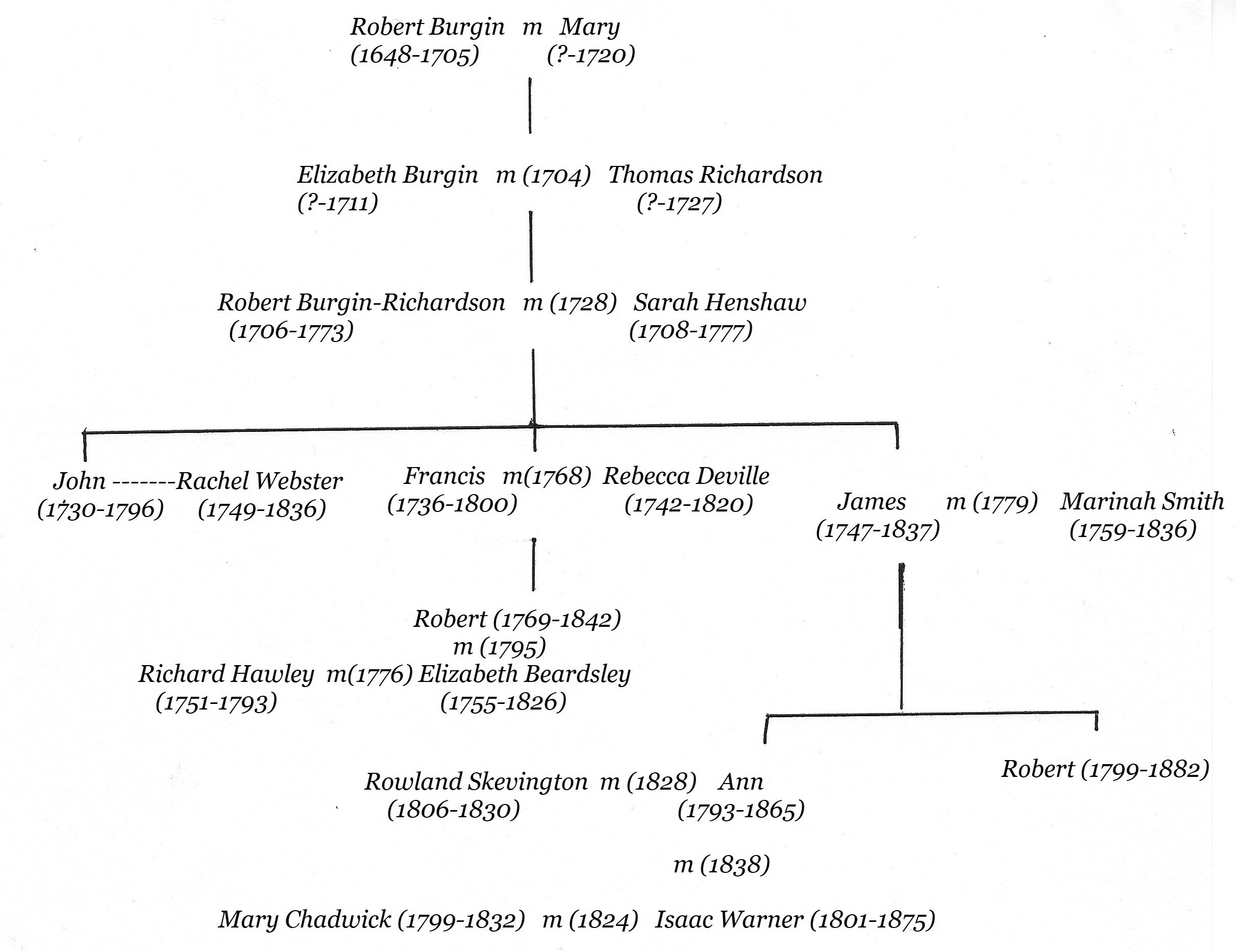

The following account is compiled from the notes of the local historian, the late Edgar Waterhouse, as well as from 18th and 19th century wills, Manor Court Rolls and St. Mary’s parish registers. It concentrates upon one family and you may (?!) find it extemely confusing … if so, move on very swiftly to the next page !!

————————————————————————————————————————————————

A short history of the ‘Market Place’ lands of the Burgin-Richardsons

Here is a much simplified family tree of the Burgin-Richardsons. Not all children are shown — only those who appear in the account — and dates are subject to question. However, hopefully you will find it useful as you navigate the ownership of the crofts in the Market Place …. or give up trying.

In the 1680’s and 1690’s blacksmith Robert and Mary Burgin of Ilkeston had several children but only one of them — Elizabeth — survived. When Robert died in April 1705, he willed his estate, including copyhold land in the town centre, to his wife and when she died, to his daughter who, in June 1704, had married blacksmith Thomas Richardson. When Mary Burgin died in March 1720, the land duly passed to her son-in-law Thomas Richardson (now Burgin-Richardson) — his wife Elizabeth (nee Burgin) had died in January 1711.

Thomas Richardson died in 1727 and the town centre lands then passed to his eldest son, blacksmith and farmer Robert Burgin-Richardson, born in 1706. Shortly after his father’s death, Robert married — April 6th 1728 — Sarah Henshaw, daughter of James and Alice (nee Bullock) of Ilkeston.

Robert died in December 1773 and his widow Sarah in January 1777. The estate then passed to their eldest surviving son, blacksmith John Burgin-Richardson (born in 1730). On the map, this included the crofts numbered 3 and 5, as well as the two crofts named as Ley Hays (or Heys) …. Ley means grassland used temporarily for hay or grazing.

On July 21st 1786 John sold a small part of the croft numbered 3 so that a Methodist meeting place could be built upon it. This was later known as “the Old Cricket Ground Chapel“

John died in January 1796 and he bequeathed to his housekeeper Rachel Webster, the house he was living in with her (numbered 5 on the map), together with other buildings and land. After her death (which occurred on February 14th 1836) the property was to pass to John’s nephew Robert Burgin-Richardson (born in 1769), son of Francis and Rebecca (nee Deville). His brother, Francis, father of Robert, was to receive another portion of the estate while the same nephew Robert was to inherit land adjoining that of his father. The residue of the estate was passed to James Burgin-Richardson, a younger brother of John — this included the croft numbered 3 on the map.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

So, at the turn of the century, much of the land at Ilkeston town centre (and beyond !!) was in the hands of the Burgin-Richardson family.

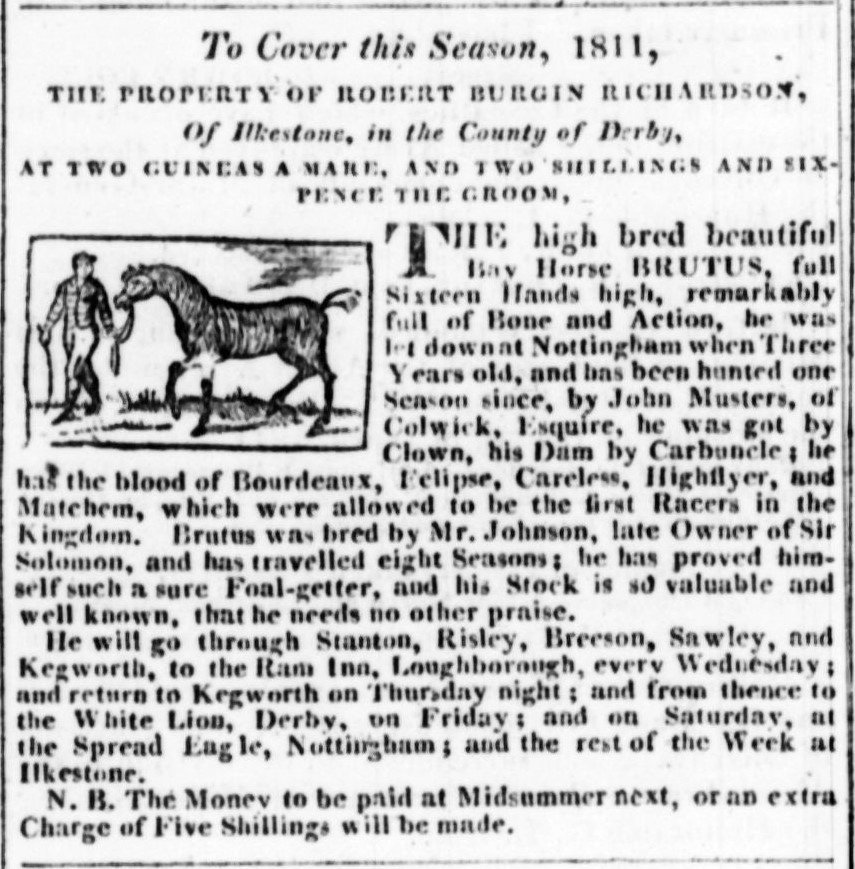

The croft in the possession of ‘nephew’ Robert Burgin-Richardson is marked, along with his homestead within that croft. The crofts at 1 and 2, and the houses within them, were also owned by Robert with his father Francis Burgin-Richardson, a wheelwright. Is this where Robert kept Brutus ?!

A busy boy (Nottingham Review, May 10th, 1811)

Francis died in July 1800 and left to his son Robert, his Ilkeston copyhold property in the town centre, granting his wife Rebecca two rooms to live in for the rest of her life … if she so wished … as well as an annual stipend. If Robert were to die without heir then the land would pass to Francis’s two daughters, Sarah and Alice. (At this time Robert was married to Elizabeth Beardsley, widow of Richard Hawley; their only child, Francis, had died in infancy in 1796. Richard Hawley, who died in December 1793, had tenanted this homestead before Robert Burgin-Richardson).

Francis also left to his son Robert his freehold estate at Hunger Hill, together with three houses there, yards, gardens, etc, plus rights to a well on Richard Beardsley’s croft — very important !!

Francis’s daughter Sarah and her husband, John (also called Burgin-Richardson just to make things a little more complicated !!), were bequeathed an estate, Little Hare Close, down Moors Bridge Lane (Derby Road), and two houses in Burr Lane.

There were several other bequests and regulations about inheritance.

Robert’s uncle, James Burgin-Richardson, still owned the croft at 3, and the premises within it, which included a blacksmith’s workshop. And remember, on the eastern border of this croft was the old Methodist Chapel, later known as the Cricket Ground Chapel.

In April 1801 and some years after his marriage to Elizabeth Beardsley (on February 16th 1795), ‘nephew’ Robert, with his wife, had taken possession of the croft, numbered 2 on the map. This included three dwelling houses, in one of which lived Robert’s widowed mother Rebecca, until 1820 when she died. By 1817 there were six houses on this site. The residue of the estate which had not been named specifically in the will passed to John’s brother James, also a blackmith, as well as that part of his premises numbered 3.

James Burgin-Richardson died on June 30th 1837, aged 90, and in his will he bequeathed to his son Robert, his house and his part of the blacksmith’s shop … all numbered 3 on the map. To his daughter Ann, now the widow of the late Rowland Skevington, James left a homestead and two other houses, plus outbuildings, yards and gardens, also in the croft numbered 3.

On October 14th 1838, Ann Hawley (nee Burgin-Richardson) married Isaac Warner.

4 is the approximate site of Weaver Pool

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

So let’s now move on in time to see how the area had changed as we enter the Victorian era