After the premises of John Moss …

Gladstone Street.

Adeline recalls that “Gladstone Street was merely a track, very muddy in bad weather, and as there were no houses in it, was avoided as much as possible”

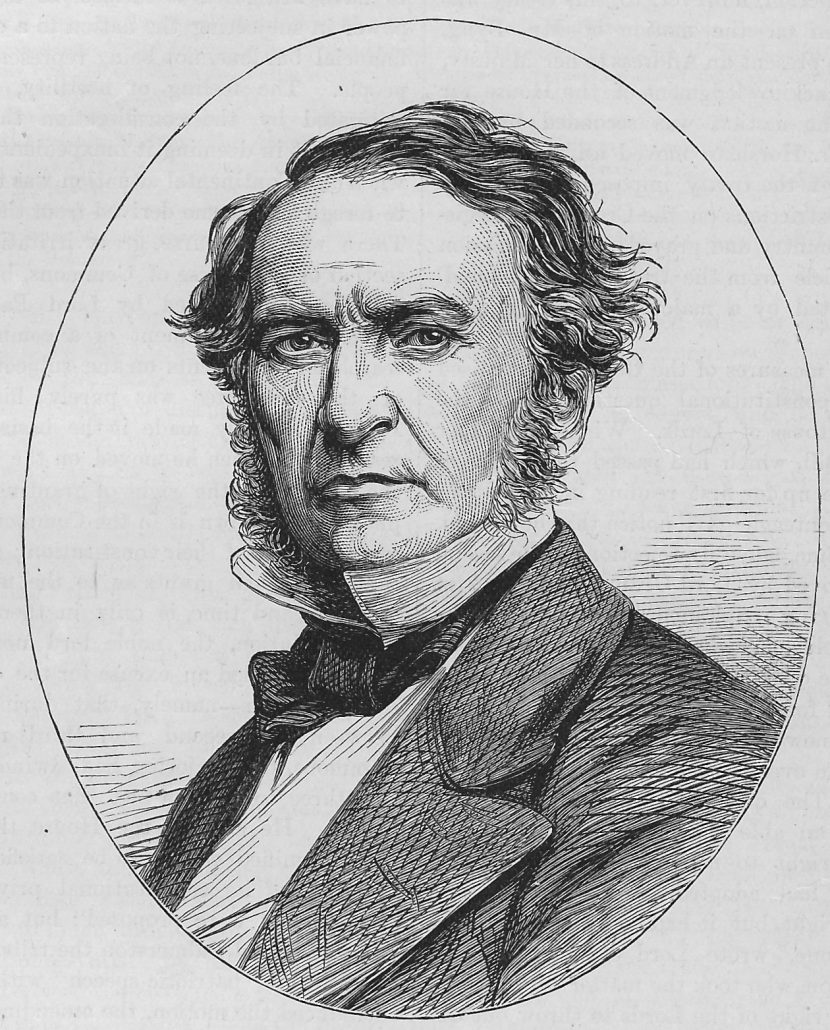

Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone (left) first became Prime Minister in 1868.

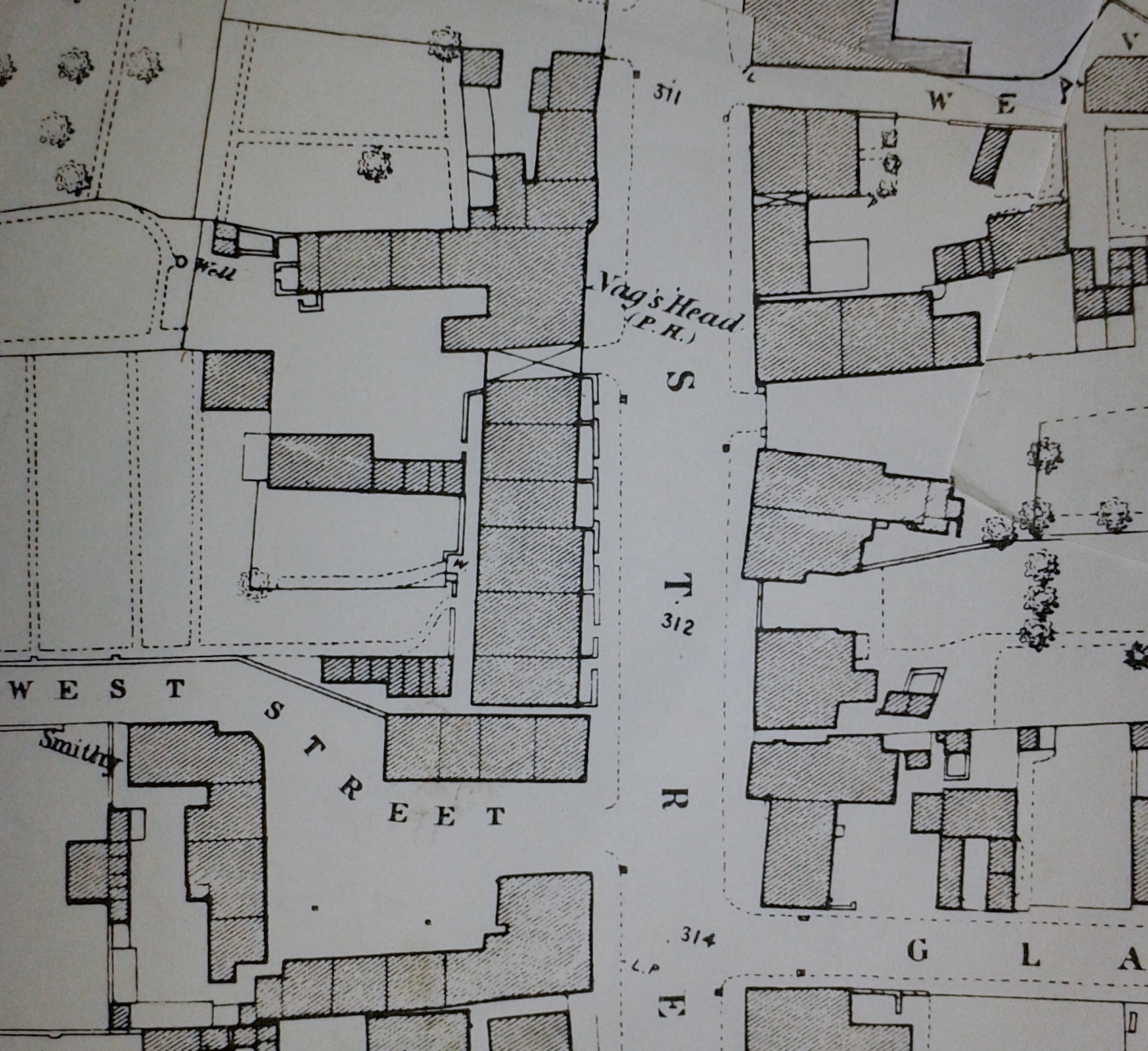

On the 1866 Sherwood Newman map, drawn up for the Local Board, Gladstone Street is named as Pledge Street.

Perhaps the origin of this name — which didn’t last long — lay in the fact that on the southern corner of this street as it entered South Street we find the pawnbroker’s shop of John Moss !!??

(Pledge: noun … a thing that is given as security for the fulfilment of a contract or the payment of a debt and is liable to forfeiture in the event of failure.)

The change of street name in the late 1860’s may have been as a result of Gladstone’s elevation to the post of Prime Minister and the Liberal majority on the Local Board.

Adeline believed that “Mr. Paling, wheelwright, of Trowell, was the first to put up a building in Gladstone Street.”

Gladstone Street — along with Market Street and Albert Street — was sewered, levelled, paved, flagged and channelled by Reuben Shaw in 1874.

In the following year he did similar work at Havelock Street, Oxford Street, West Terrace, North Street, Crichley Street, Slade Street and North Gate.

Samuel Paling was the Trowell wheelwright. He came from a long line of carpenters and wheelwrights of Trowell and Lowdham.

Right is a photo showing the remains of a wheelwright’s forge, last belonging to Henry Paling, once to be found in Gladstone Street, and in use after the 1939-45 War. (from the personal collection of Jim Beardsley)

Henry’s father John was born in Lowdham and came to Ilkeston just after his marriage in 1872 to live in Gladstone Street.

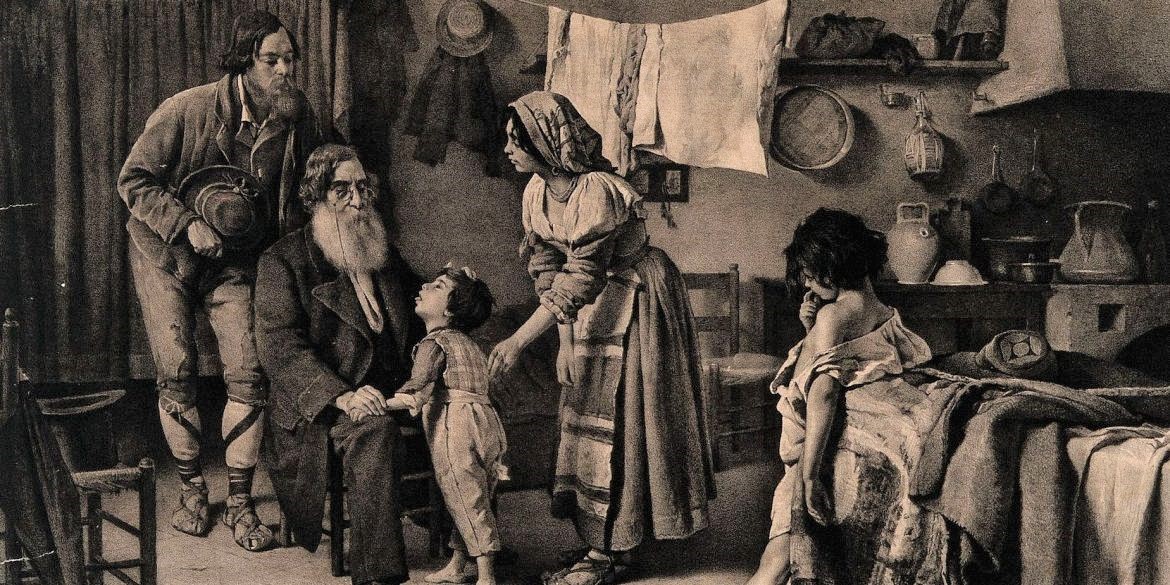

Destitution in the street, 1885.

About ten years after Reuben Shaw had ‘improved’ the fabric of Gladstone Street, Wright Wallace and his family arrived there. Previously from Liverpool they had lived in Park Road, Ilkeston, before moving into Gladstone Street at the beginning of 1885. There had been eight children in the family, though two had died and one was working away from home. The father had just secured a job, down Nottingham Road, as a warper with Messrs. Tatham Bros., at their Kensington Works, earning from 30s to over £2 a week.

In February 1885, the mother, Caroline, was heavily pregnant and was being attended by a neighbour, Elizabeth Doar, who lived a short distance away in Weaver Row. One day, Elizabeth brought round some clothes for the anticipated baby as Caroline had nothing for it to put on. At that time the neighbour noticed that the six-year-old daughter, Sarah Ann, was curled up on a mattress infested with vermin, by the fireside. A short time later, on February 28th, she visited again, and this time Sarah Ann was upstairs, wearing an old black jacket and lying on a putrid, dirty mattress on the floor. There was no furniture at all, no fire in any room and as far as Elizabeth could see, no food in the house. And almost as soon as Elizabeth arrived Sarah Ann died quietly. Her filthy body, which weighed only two stones, was then washed carefully.

It transpired that the daughter had been ill for about three months, initially with a whooping cough. Because the family was on the medical relief book, she had received some medicine from Henry Potter, medical officer to the Basford Union, who had recently taken over that role from Robert Wood. The medicine had seemed to revive Sarah Ann temporarily, but when her mother asked for more, the doctor refused — the husband was now in regular employment and so was not entitled to a free medical service. The doctor thought that it was want of food more than lack of medicine which was causing her discomfort. Perhaps what the doctor did not know was that most of what Wright Wallace earned was spent on drink for himself; Caroline never saw him until he arrived home drunk at night. He provided some groceries and flour but when they were gone the family was allowed no more. They had meat to eat about once a fortnight and Sarah Ann had had no more than apples to eat when she was ill. However the doctor might have been alerted by the fact that the only foord he saw in the house was a bit of bacon and a herring; and the house he saw was utterly destitute — the most destitute that he had seen in his life.

At the inquest on March 2nd, 1885, held at the Nag’s Head Inn, the Coroner and his jury were appalled by what they now heard. The dead child had almost been allowed to waste away — her weight was half of what could be expected and, at 3 ft 3ins, she was six inches less than the average height. Her bowels, left kidney and lungs were diseased, there were signs of old standing pleurisy, but acute tuberculosis or the ‘galloping consumption’ was fatal — and once it had taken hold, could not be stopped. There had been shameful neglect but the Coroner could find no sufficient evidence to conclude that this solely had contributed to Sarah Ann’s death; consequently a charge of manslaughter against both parents would probably fail. However he made clear to both of them that they were morally responsible for the death. The father, who by then was too intoxicated to be sworn in, tried to pass on the blame to his wife who was also ‘under the influence‘ — despite bringing home 35s in the week, he had had to pay down debts owed by Caroline. To this the Coroner voiced the opinion that he was a disgrace to humaity.

Two days later Sarah Ann was buried at St. Mary’s churchyard, after passing through a large crowd assembled at the church gates — another, similar crowd had earlier gathered at her home in Gladstone Street — and at both venues the police were conspicuously present. Feelings were running high against her parents.

Shortly after, the Wallace family left Ilkeston for Nottingham. But the parents escape from the town did not mean their escape from the law. In May 1885 the pair appeared before the Ilkeston bench of magistrates, charged under the 37th Section of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1878 — that they did on and since the 1st January last, at Ilkeston, wilfully neglect to provide Sarah Ann with proper and sufficient food and clothing, whereby her health was so impaired that she died.

Suffer the Children, from the Social Historian

Their prosecution was taken up by the newly-established Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SPCC), and the case was duly proven. Both the culprits were sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour, the maximum that the law would allow, and a punishment that ‘they richly deserved; they had narrowly escaped being charged with a much graver offence’.

Within the Wallace family, young Charles, aged 2, had died just before Sarah Ann, and baby Joseph who had been born in Ilkeston in early 1885, died in Nottingham just before the trial of the parents.

More child abuse: 1894

Within the next decade the SPCC had become the NSPCC and pursued several other examples of abuse occurring in Ilkeston. By 1894 the Children’s Charter (The Prevention of Cruelty to, and Protection of, Children Act 1889) had been passed. This allowed the authorities to prosecute parents who, whilst not physically mistreating their children, were neglecting them and thereby putting them in danger. Thus in November 1894 the Society raised the case of coalminer William Fretwell, a resident of Bridge Street, living there with his wife Sarah Ann (nee Clower) and their eight children, six of whom were under the age of 16. The father was an idle drunkard, who did very little work but relied upon the income of his two grown-up coalminer sons, John (aged 21) and Robert (18), to bring in 12s each per week. This was handed over to their mother to pay for rent, food and clothing, though some went to William for him to buy drink. When this was not enough he resorted to pawning the children’s clothing and the family furniture. There was no food, fire or coal in the house, very little furniture and almost no bedding, when it was visited by Inspector Cooper of the SPCC — just three sheets and a lot of very old clothing.

When William Fretwell appeared in court, he asked that he ‘be given a chance’. Well, what he was given was three months in jail. Being led away he promised that he would be damned sight better when he came out !!

the end of Gladstone Street, taken in 2000 … the South Street end is behind the photographer.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Amos and Elizabeth Burrows

Back into South Street and “Mrs. Burrows had the first house past Gladstone Street” — at 51 South Street (East Side).

“She did a good trade with her public mangling” recalls Adeline.

Elizabeth Garton, daughter of John and Mary (nee Carnall) was born in Stapleford about 1810 and married Amos Burrows, general labourer and the son of Robert and Mary (nee Tatham) in March 1829.

The couple lived most of their lives together in South Street where Amos died in December 1878.

Elizabeth continued to live in the family home but later moved to Lawn Terrace to live with her daughter Jane who had married George Shaw, coalminer, in August 1864.

Elizabeth died at 6 Lawn Terrace in 1891, aged 82.

Robert Burrows was an older brother of Amos. He was born about 1803 and also lived in South Street were he operated an omnibus running between Ilkeston and Nottingham. He died of chronic bronchitis on September 5th, 1844, aged 42.

South Street, from Gladstone Street to Weaver Row, about 1880

We are now walking along the east side of South Street, from south to north (bottom to top) towards the Market Place. On our right we pass Gladstone Street (spot it at the bottom ?) and walk towards Weaver Row (top right ?)

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Flint Hawley.

Adeline leads us on, to “the next shop which belonged to Mr. Flint Hawley, butcher”.

The members of this family were prominent in the Congregational Church.

Edwin Flint ’Ted’ Hawley, the only son of South Street butcher John and Mary (nee Burgin-Richardson), and Elizabeth Ann Stanley, daughter of engine worker James and Ann (nee Slack), married in August 1851.

From that time Ted traded in South Street as a butcher.

“The front room of the house had been converted into a butcher’s shop, which was approached by several steps. The window was an ordinary house one and I think the shop had been added on to the house, for it stood out from the two buildings on either side”.

Flint Hawley’s converted shop had a window which opened up onto the street and within which the butcher would display his wares — and at times would leave it open. This could be a great temptation for passers-by …. as it was to Mary Harriman one Saturday evening, just before the New Year’s Eve of 1865.

Leaving a couple of lads in charge of the shop at about five o’clock in the evening, Flint had just left, sauntered across South Street and was parked about 25 yards from his shop. From there he saw Mary wander past the window, stop, turn and return …. whereupon she lifted a joint of beef from the window board and then walk on towards White Lion Square.

Time for Flint to step in.

He caught up with Mary to confront her … and suddenly the joint appeared at their feet. Mary denied any knowledge of it, though Flint was quite certain that he had seen it fall from beneath her shawl. The butcher insisted that Mary go with him — and the beef — to Inspector Brady who seems to have believed Flint. He had known Mary for four or five months — living in Grass Lane, she was the wife of miner James Harriman, and had been in Ilkeston for about two years, having come over from Canada with her husband.

Still positively denying the theft, Mary appeared at Smalley Petty Sessions on New Year’s Day and thereafter spent the first three months of 1866 in jail.

“Mr. F. Hawley died in middle age, leaving a widow and four children”.

Flint died in South Street on May 9th, 1868, aged 37, by which time four of his five children were still alive – the youngest, Harry Stanley, being a few days short of his first birthday.

Their mother, widowed for almost 40 years, died at 1 Gladstone Street on April 4th, 1907, aged 80, suffering from influenza.

The Hawley children

1. “Mrs. Hawley carried on the business until Ted, the eldest son, was old enough to help her”.

Widow Elizabeth Ann and son Edwin Flint continued in the trade. The latter married Lydia Henshaw in April 1874, she being the daughter of Cotmanhay labourer and one-time innkeeper at the Rose and Crown William and Sarah (nee Aldred).

2. “Annie, the eldest daughter, married Philip Bacon, grocer”.

Just across the street – at 42 South Street in 1881 — was daughter Mary Ann, married on February 16th, 1880 to grocer Philip Bacon, the son of Dale Abbey labourer Daniel and Mary (nee Cotton). She remained there after her husband died in 1903.

Bacon’s Grocers, Flour, Corn and Provisions .. and a drop of beer too. (taken after the shops and houses of South Street were renumbered in the mid-1880s and No.42 became No.54)

To the right of the shop (photo above) you can just see the entrance to West Street, formerly Wide Yard.

3. “Florrie married a head gardener and left the town”.

Born on October 22nd, 1864, daughter Florence married Charles John Terry, gardener, in 1889 and eventually moved to Cambridgeshire where the couple kept a rural post office and garden nursery.

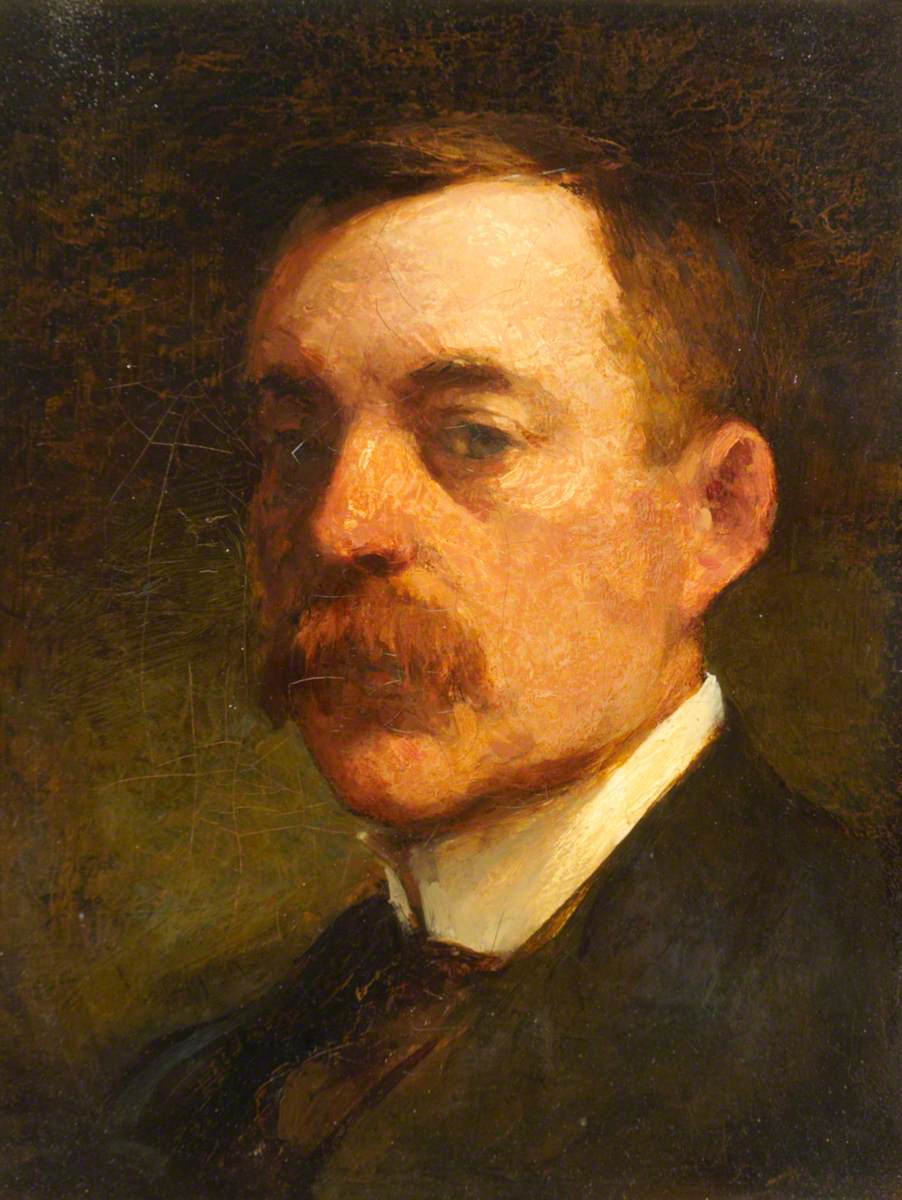

4. “Harry, the youngest, became a clever pianist, and was known as Stanley Hawley. (The name Stanley probably came from the maiden name of his mother) Unfortunately, death cut short a very promising career”.

Born on May 17th 1867, Harry Stanley attended the British School in Bath Street and then moved on to Derby Grammar School where in 1881 he obtained a Rowland scholarship of £25 per annum to cover the cost of two years’ tuition at the school.

In January 1882 he was appointed organist at the Independent Chapel in Pimlico, succeeding his older brother Edwin, and fulfilled the same role for the Ilkeston Harmonic Society.

“It seems but yesterday since he was lifted onto the music stool at a Christmas school concert, to take part in a duet on the pianoforte with his sister Florrie”. (Sheddie Kyme)

At the age of 16 Harry Stanley won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music where, in July 1885, he was awarded the bronze medal for pianoforte playing, as well as honours in other departments of music. “Mr. Hawley has performed with considerable successat the Inventories Exhibition”. At that time he was tutored by Professor Arthur O’Leary.

Earlier that same year he had been engaged by a firm of organ builders to display its new instrument at the International Inventors Exhibition in the capital.

And later that same year he was back in Ilkeston, conducting an afternoon programme of musical entertainment at the Town Hall, helping to raise funds for the Cottage Hospital in Station Road.

In July of 1886 it was announced that Harry Stanley had now been awarded the Academy’s silver medal for piano playing and the bronze medal for harmony.

Throughout this period he was performing in local concerts, often with the Ilkeston Harmonic Society, before departing, around 1890, to live in London.

There he joined the ‘concert circuit’, whilst composing songs for fellow musicians. He was also employed as the organist at St. Paul’s Church at Winchmore Hill, London, a post he had taken up in 1885 … and was now being described as ‘a sub-professor of the Royal Academy of Music‘.

In April 1890 Harry Stanley returned to Ilkeston to play upon the newly ‘restored/renovated’ organ of St. Mary’s Church. (Before the recital the newly ‘installed’ Vicar, Edward Muirhead Evans, encouraged the audience to donate liberally towards clearing the organ debt of around £300). The recent deaths of William Sampson Adlington J.P. and the wife of George Searle Ebsworth were the occasions to preface his recital by playing the ‘Dead March in Saul‘. There followed several organ pieces by Harry Stanley as well as choir music — “Mr. Hawley’s manipulation of the instrument gave the most eminent satisfaction” — ‘he may be congratulated on having enhanced his already high musical reputation’. (Long Eaton Advertiser April 12th)

In the following month, the Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts engaged him to play an organ recital at St. James Hall, London, to the guests of the Emin Pasha Relief Committee who had been invited to meet journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley. At this event and on the arrival of the Royal family, Harry Stanley played the National Anthem while he greeted the explorer musically with ‘See, the Conquering Hero Comes’.

And then Harry Stanley moved amongst even more exalted company …

Court Circular, July 1890. OSBORNE, Friday

The Queen drove out yesterday afternoon, accompanied by Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein.

Their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Connaught and their children, attended by Lieutenant Colonel Becher arrived at Osborne in the afternoon from London.

Mr. and Mrs. Standish had the honour of dining with her Majesty and the Royal Family.

In the evening the following gentlemen had the honour of performing the following selection of music in the Drawing-room before the Queen and the Royal Family:–

…..Piano solo; ‘Album Blatt’ (Greig) … Mr. Stanley Hawley, Royal Academy of Music …(etc)

This was possibly a ‘treat’ for the Duchess of Connaught whose birthday it was on the following day. It was also a treat for Harry Stanley who was later presented to the Queen.

And honour followed honour .. in the same month, at the annual prize-giving of the Royal Academy, through ‘the kindness of the Worshipful Company of Musicians‘, Harry Stanley was the first recipient of the new silver medal, awarded to ‘the most meritorious’ student in the (Royal) Academy… that is, not necessarily the most gifted but the one who had shown the most attention and punctuality combined with talent, and had assisted the managers of the Academy by setting an example in the important matter of general good conduct’.

On one side of the medal was displayed the arms of the Musician’s Company while on the reverse was a draped figure playing a lyre. (see below)

The Derbyshire Courier (Aug 1890) concluded that ‘Mr. Hawley’s career … has so far been a brilliant success‘. (https://www.wcomarchive.org.uk/–ramrcmgsmd-silvers)

In a column from the Nottingham Evening Post (September 1890), sandwiched between the Midget Minstrels, Vento the ventriloquist, and Lily Langtry, Harry Stanley was announced as the pianist at the formal re-opening of the renovated Nottingham Mechanics’ Hall organ … the organ itself was played by Edwin Henry Lemare.

And, in late September 1890, Harry was back, once more, at Ilkeston Parish Church, trying again to reduce the debt on St. Mary’s Church organ. Aided by several artists from the R.A.M., he gave two concerts — afternoon and evening — in aid of the Organ Fund. And in the following year (June 1891) he was once more playing on the renovated and enlarged organ.

In the summer of 1892 Harry Stanley was appointed organist at St. Peter’s Church, Belsize Park in London, a post previously held by the aforementioned Edwin Henry Lemare.

Into the 1890’s and he was composing more of his own music including his work in ‘musical recitations’. These were interpretive accompaniments for several well-known poems (eg. ‘The Bells’ and ‘The Raven’ by Edgar Allan Poe; Charles Kingsley’s ‘Lorraine, Lorraine, Lorree’; ‘Riding through the Broom’ by George John Whyte-Melville), and described as ‘a drawing-room form of light melodrama, lately in favour’ (Manchester Courier July 1895) and which some critics felt was a pleasure enjoyed by only a minority of music lovers. Like it or not, all Harry Stanley’s work was available through ‘Messrs Robert Cocks & Co, New Burlington Street, London, Music Publishers to Her Majesty’.

This was however a style of composition to which Harry Stanley seemed well-suited and which was to continue throughout his musical career. Generally his work in this genre was highly-regarded though there were dissenters !!

Music Reviews…

A musician who is rapidly and deservedly coming to the fore .. Morning Post, May 1896

A pianist of repute … Cardiff Times July 1896

Mr. Stanley Hawley … has made (the rage for recitations with musical accompaniment) immensely popular, particularly in concerts and entertainment of the better class ..Merthyr Times January 1897

Stanley Hawley is well up to the work of adaptation .. London Daily News February 1897

The clever musical illustrations of Mr. Stanley Hawley .. The Era January 1898

and a layman’s view ….‘one of Ilkeston’s greatest musicians’ .. Charles Maltby of Dalby House March 1899

January 28th, 1898 and Harry Stanley was back in town, to conduct “one of the most excellent and high-class concerts ever given at Ilkeston“, at the Town Hall. This was the first concert on his own behalf given in his native town and the crowded house included Ernest Terah Hooley (obviously keen to patronise the electorate who would return him as their M.P. at the next general election, he expected). This was followed, just over a year later, by another appearance, this time at the new Wesleyan Church in Bath Street — an organ recital in aid of the building fund. No-one would argue that Harry Stanley neglected his birthplace !!

In May 1905, after Harry Stanley had been composing his works for many years the music critic of the Manchester Courier dissected his most recent work … the composer having usually succeeded in supplying an appropriately tonal background for the reciter .. it seems to us, however, that the artistic quality of Mr. Hawley’s musical accompaniments would gain much by a less lavish indulgence in chromatic harmonies;and certainly the avoidance of such a prodigal display of accidentals in the musical score, would render the music much more readable and less formidable to the average pianist.

It seems that Harry Stanley took heed of this criticism — at least eventually. By 1914 he was producing and editing the ‘celebrated series’, ‘Hawley Edition of Pianoforte Classics’, the primary intention of which was to reduce the difficulty of reading the compositions by altering the notation to cut the number of accidentals to a minimum. As he explained, ‘It merely clears from the pages all the trifles; what you see is certainly different, though what you hear is quite the same’.

By the end of 1908 he was Director of Music at the Kingsway Theatre in London….. and by 1915 he was ‘one of the best-known musical personalities in London’ (Reading Mercury March 1915)

In the late spring of 1916 Harry Stanley was taking part in a concert given by the Three Arts Club when he was taken ill. He had developed a blood clot on his brain and accompanied by ‘his faithful friend’ John Mewburn Levien — Professor of Singing and director of the Positive Organ Co. Ltd. of Mornington Crescent, London — he was returned from London to ‘Depedale’ in Ilkeston, the home of his sister Mary Ann, in Derby Road. There he was solicitously attended by Mary Ann and his other sister Florence who had arrived from St. Neots but he died at 2.30pm on June 13th, 1916, aged 49.

The burial took place on June 17th and the cortege travelled from Derby Road along South Street to a service at the Parish Church. “Many reverent spectators en route to the church witnessed the sadly impressive procession, and a great many blinds were drawn in token of respect and esteem for the memory of a beloved townsman who, although his great gifts had called him away to more brilliant spheres of usefulness, never forgot and was always proud of his native place. The high position he occupied in musical circles in London was evidenced by the beautiful floral tributes from every leading organisation and from a number of well-known artistes in various walks of life. Many local wreaths were sent, the total reaching fifty. Mrs. Fletcher, Albert Street, who assisted Nurse Bowker for the funeral, placed a bunch of forget-me-nots on the body as a last tribute’.

Harry Stanley was buried at Park Cemetery. In 1907, at the funeral service of his mother at St. Mary’s, he had played at the Church organ. Now that same organ was played at his own funeral service nine years later.

In the following month the Musical Review included an appreciation of Harry Stanley.

It noted that “as far as the musical profession, everyone in West London circles knew and loved him”.

“Living in chambers close to West End concert halls, Mr. Stanley Hawley was able to put in appearances and to answer calls upon his time with all the willingness that so well became him. He never spared himself to do a kind action. If he found a student or friend who specifically wanted to go to a concert, a ticket was at once produced. He never thought of himself when there was an opportunity open for his generosity. Nor was there any jealousy in his nature where fellow-musicians were concerned. Good humour and the desire to make life pleasant and to be of service were his ruling passions”.

Adeline’s memory of son Harry Stanley is echoed by that of Richard Benjamin Hithersay in 1933 who recalled…..

“a promising young product of Ilkeston. He must have had musical attainments of a high order, for after creating a considerable local reputation as a pianist and organist when quite a boy, he came to London, and was for years a prominent member of the Philharmonic Society. But the Metropolis, unfortunately for individual aspirations, contains a multitude of capable and gifted musicians, and it’s a wonderful place for knocking the conceit out of youthful genius. Many years ago I chanced to see a brief obituary notice of Stanley’s death at an early age, (adding somewhat cruelly) so he passed away without ‘setting the Thames on fire’”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Finchs.

“Mr. and Mrs. Finch lived in the double fronted house next to Flint Hawley, the butcher. Mrs Finch was formerly Miss West of the Market Place”.

‘Miss’ Mary West was a daughter of William Barnes West and Hannah (nee Twells), drapers of the Market Place. When William died in 1831, his widow continued to trade at ‘West’s General Drapery Establishment’ assisted by several members of her family, including daughter Mary.

In 1859 Mary married William Finch and the couple appear on the 1861 census as neighbours of Flint Hawley and family.

Eventually William and Mary went to live in Basford where they were joined by Mary’s younger sister Martha.

Mary died in 1876 and in the following year William Finch married his sister-in-law Martha.

And in the following year William died.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Raynes’ residence.

“Next another double fronted house occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Raynes, two sons and three daughters — at what was later 49 South Street (East Side). Mr. Raynes was a book-keeper at Stanton”.

Joseph Raynes, son of Joseph and Lucretia (Shuttlewood), was born in Loughborough in 1815, traded as a lace merchant in Nottingham in the 1840‘s and married Elizabeth Wild at All Saints Church, Derby on February 10th 1850. She was the daughter of Nottingham printer Henry and Rosehannah (nee Shaw). At that time Joseph traded from his ‘London House Millinery and Bonnet Show Rooms’ at Long Row, Nottingham. The trade was not however well-managed and at the beginning of 1854 Joseph was bankrupt

The family moved from home at 55 Long Row, Nottingham, lived for a short time at Wesley Row, Stapleford, and about 1857 arrived in Ilkeston where they took up residence in South Street. Joseph was now working at Stanton Ironworks as a cashier.

In 1861 the family was living in South Street at the location indicated by Adeline.

Joseph died in South Street in February 1871, aged 55, when the Pioneer recorded him as “formerly cashier at the Stanton Iron works”. Elizabeth left South Street to move into the White Lion Square area of Nottingham Road and eventually into Havelock Street where she traded as a dressmaker.

“Edith, Agnes and Dorothy were the girls, and James Henry, the surviving son. The eldest boy died young”.

In order of age the children were Adah, James Henry, Eliza Agnes, Joseph Augustus, Lucretia Rosannah and Alfred Ernest, the latter born in 1861.

Joseph Augustus died in October 1878, aged 22. By that time the family had moved to Yew Villa in Nottingham Road.

Both Lucretia Roseannah and Alfred Ernest attended the Art Night Class in Ilkeston in the mid-1970’s and each won several prizes there.

RBH lived very close by and from early boyhood was ‘intimately associated’ with Alfred Ernest.

“He was probably one of the most gifted youths Ilkeston has ever turned out — a talented artist, a good singer, swimmer, sculler and all-round sportsman, and altogether a very interesting personality. His one weakness or idiosyncrasy was an incurable liking for appearing in attire of the latest London fashions, received direct from a brother of his at Whiteley’s. I am afraid this habit excited much more ribaldry than admiration on the part of the younger inhabitants; but this made not the slightest difference to Raynes, who pursued the even tenour of his way with the impassivity of the Egyptian Sphinx”.

Alfred Ernest appears on the 1881 census with his family at Havelock Street, as a solicitor’s general clerk and RBH recalled that for some years he was managing clerk to solicitors Thurman & Slack — described in Wright’s Directory of 1883 as “solicitors and clerks to Heanor Local Board, Ilkeston School Board, solicitors to Erewash &c. Building Societies, 115 Bath street”.

Alfred Ernest was still working for them in June 1884 when, alighting from a trap outside the Church Institute in Market Street, he fell heavily, cracked his head on the ground and was rendered unconscious for some time

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The South Street Registered Lodging House at 55 South Street

We started this section with “destitution in the street, 1885“. We move on to 1900 and more destitution.

On the evening of Wednesday, March 14th, 1900, Paul Lebeter, keeper of the Working Men’s Home lodging house, received ‘guests’ at his establishment. The police arrived pushing before them a fish barrow, lying upon which was an old woman, about 70 years old and in a very poor state. She had been picked up by a P.C. outside the Poplar Inn in Bath Street although there was no suggestion that she was drunk or had been drinking. The police knew very little about her as she was a stranger to the town, having come from Nottingham; what they did know was that her surname might be ‘Neal’ but had no other name. Sadly Paul was full up — he had no spare beds but he did make up his fire which she could sit by and warm up. As she rested there, she wanted nothing to eat though several inmates made tea for her to drink.

The old woman rested there until about noon the next day, She then set off to find the relieving officer but on her search she appears to have been distracted — Paul saw her in the Market Place carrying a pint pot and visiting the Harrow Inn and other pubs in that area. As the evening of that Thursday approached, the wanderer had made her way to Granby Street where she rested on the doorstep of number 14, the home of yeast maker George Wright, and where she was invited in by George’s mother-in-law, Harriet Shaw. Again she refused anything to eat but took a drink of tea, and revealed a little more information about herself. She wasn’t ever married, had no children but had a brother in New Zealend who she hadn’t heard from for years. The last solid food she had eaten was about three weeks previous and she had but a few coppers on her. After about twenty minutes she politely thanked Mrs. Shaw and left, having been advised to go to Basford Union Workhouse, though she didn’t know where it was or how to get there.

Next to enter into the story was collier Arthur Aldred of Awsworth Road, walking opposite the Trinity Church in Granby Street, when he stumbled into “Miss Neal” lying on her back in the gutter and who by this time had been surrounded by a jeering, mocking crowd of factory girls and pit lads. Arthur helped her up and tried to lead her into the churchyard, away from the crowd. He shouted to them to get back, but before he could take the old woman any further, she stumbled into the road. A constable arrived and together they once more tried to assist her but by that time it was too late. Her lifeless body was carried once more, this time to the nearby Mundy Arms.

During her last hours several policemen had made contact with her at several locations around town, had offered to take her to friends (though she had none), to take her to the train station and pay her fare to get her to the Workhouse. To arrange this, they had visited the relieving officer, William Nunn of Jackson’s Avenue but he wasn’t interested and was very off-hand (as interpreted by the police inspector). Even though he was informed of the parlous state the old lady was in, William declared “It’s no business of mine. I’m not supposed to run after people that want relief“. He was told that she could barely walk and so really couldn’t travel very far. “Well, if she’s comes to me, I will give her her railway fare and a ticket for the workhouse“.

At the inquest into her death, several people in the sorry story were praised while others were strongly criticised by the jury. The crowd and William Nunn (who couldn’t be found to attend the inquest) didn’t fare very well, while Arthur Aldred and the police involved were singled out for praise by the Coroner, The foreman of the jury was Councillor Joseph Scattergood, a member of the Basford Board of Guardians, who would doubtless question William Nunn on his conduct that day ?

Verdict: Death from natural causes, viz., syncope.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Amos Beardsley, baker.

“When Mr. Raynes died the two front rooms of this house were turned into two shops and taken by Mr. Amos Beardsley, baker, and Mrs. Beardsley, milliner.

“The old building in the yard (now demolished) was where Mr. William Hawkins started his foundry. This place was used for printing later and Mr. Beardsley had the back part for his bakehouse”.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

We are now opposite the Nag’s Head and time to consider the Beardsleys and Birchs in more detail.