After the three empty shops “then came Carrier’s factory yard. The lace business of Henry Carrier & Sons was, I believe, commenced by Henry Carrier in the late twenties or early thirties, but as I have no access to either deeds or records I cannot say which.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

At this point we will pause to learn a little about this Carrier family in Ilkeston. But we have to be careful not to become confused — there are several ‘Henry Carriers’ to consider.

In Glover’s Derbyshire Directory of 1829, Henry Carrier is listed as a Copyholder, a grocer and lace manufacturer. This is Henry Carrier, born in 1779, who had an uncle Henry Carrier (abt 1744 – 1812), from whom he inherited property, and a son Henry Carrier (1806 – 1881), to whom he left property. (He is also listed as a ‘lace manufacturer‘ in Pigot’s Derbyshire Directory of 1829).

He reappears in the 1835 Pigot’s Directory as both a grocer and a lace manufacturer.

On the 1841 census he is trading in Bath Street, as a draper and grocer, next to his brother Anchor Carrier.

Because his uncle Henry died in 1812, and because he had a son Henry, we will refer to this Henry as Henry senior

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Henry Carrier senior (1779-1852), his wife and children

Henry senior was the son of John and Esther (nee Woolin). The Carriers were members of the Wesleyan Methodist society, and Henry senior was one of the first superintendents of their Sunday school, as well as a class-leader, steward and trustee of the Church.

On February 10th, 1802 Henry married Elizabeth Smith, a daughter of joiner Jervas and Elizabeth (nee Chevin) and the sister of Dorothy Smith. The latter had married baker and victualler John Hives in 1801 and their son, Thomas Hives, was to be the landlord at the Rutland Arms Hotel.

Henry and Elizabeth Carrier had at least seven children.

1 … First son Henry died in infancy in 1803.

2 … Adeline recalls “Henry junior, the eldest, went to Nottingham to manage the Mount Street Warehouse. He married in middle life Mrs. Gadd a widow, who had a life interest in Gadd’s factory, Peveril Street, Nottingham.”

Born in 1806, lace and hosiery manufacturer Henry junior (the second) was the oldest surviving son and, in later life, the senior partner in the firm of Henry Carrier & Sons. He married Frances Gadd (nee Bucknall), widow of lacemaker John, on November 11th, 1858 when he was aged 52 and she was 60. At that time the address of the family firm was at 6 Mount Pleasant, Mount Street, Nottingham, though the couple lived at Peveril Street, Sherwood. Frances died there on March 13th, 1866 and Henry on September 23rd, 1881, though he was returned to Ilkeston by his sister-in-law Jane (nee Attenborough) widow of Joseph Carrier, to be buried in Ilkeston General Cemetery.

3 and 4 … Adeline then tells us that “William and Samuel were bachelors and managed the Ilkeston business. They were with their father in the East Street Warehouse and the factory in Bath Street.

Mr. William Carrier died in 1858 or 9, leaving his brother Sam sole master. When Sam died in 1866 my father (John Columbine) became manager for the Ilkeston branch and remained as such until 1879, when he severed his connection with the firm and started in business as a lace manufacturer in Stoney Street, Nottingham.”

William Carrier died unmarried on February 16th 1858 at his East Street residence, aged 43 “to the deep regret of a large circle of friends, by whom he was greatly and deservedly respected”. (IP)

At his death his estate was divided between his three brothers and his nephew Henry MacDonald.

William’s brother, Samuel, was also unmarried and was initially a junior partner in the firm.

A résumé of his life, printed in the Pioneer (Feb 2nd 1865) explained that at the age of about 18 he had a religious conversion when he was ‘truly awakened by the Spirit of God to a sense of his sinfulness‘. He seems to have changed his outer life, sought forgiveness for his sins and joined the Church of Christ.

He was a teacher in the Sunday school and then, like his father, a superintendent, an office which he held until his death. In that role he was unconventional but well-liked by his students and took the school on to great success through his innovation, zeal and energy.

One of his projects was the home mission scheme, whereby nearly 100 young men of promise were sent out to convert sinners but which proved only partially successful. Samuel however always felt unqualified and uncomfortable in the roles of both class-leader and preacher, roles which he preferred to allow others to fill.

The laying of the foundation stone for the new South Street Wesleyan schoolrooms in 1864 and the building’s progress towards completion were witnessed by Samuel, perhaps justifiably so, as he had worked so hard for its establishment. However he did not live to see the building work finished nor the school opened.

In 1865 Samuel had been working in London and then in Nottingham, and in both places complained of feeling unwell. He recovered however and on Sunday January 15th he was working in his role as superintendent and chapel steward as well as taking his place in the church choir.

The next day saw him back working at the firm’s Mount Street hosiery warehouse in Nottingham where, on Wednesday, he suddenly became ill. Taken to the nearby house of his friend, Frederick William Goddard, in Mount Pleasant, he was attended by his warehouse manager, John Columbine, and others, but he died there a short time later. This was Friday, January 20th and Samuel was aged 46.

“The people of Ilkeston have lost a friend in the death of our late brother. Perhaps no man in the town was so well known and so highly respected. He was thoroughly a public man, and no doubt the multiplicity of his engagements drew too largely upon his physical constitution, and hastened his end”.

Samuel’s body was returned to Ilkeston on the same day as his death. On the following Sunday a funeral service was held at South Street Wesleyan Chapel which, as the Pioneer reported, was ‘crowded to excess’, with a congregation of over 1000 and with hundreds of people waiting outside. The funeral procession then proceeded to Stanton Road Cemetery for the burial which was witnessed by about 4000 people. (the Pioneer’s estimate).

5 … “Joseph, the youngest son had the grocery and drapery business in Bath Street. He married Miss Jane Attenborough, sister of the late Isaac Attenborough, landlord of the Sir John Warren Inn”.

We will meet Joseph very shortly in Bath Street.

6… “The Carrier’s daughter married Mr. Macdonald. She died in early life leaving one son, Henry Macdonald, familiarly called Henry Mac. He married Ellen, the eldest daughter of the late Thomas Hives, for many years landlord of the Rutland Hotel. Henry Mac died in the seventies, leaving a wife and two daughters.”

This daughter was Ann who married Scottish lacemaker John MacDonald on August 21st, 1832 but died just over two years later, aged 30, having given birth to son Henry – ‘Henry Mac’.

Henry MacDonald had a partnership with H. Carrier & Son but this was dissolved in 1865 when he was leaving the country. (See the Rutland Arms).

7 … And Ann’s sister Eliza died in 1837 aged 25.

Henry Carrier senior died on December 14th, 1852, aged 73. Despite what is carved on her gravestone in St. Mary’s Churchyard, his wife Elizabeth had died on December 26th, 1848, aged 70; she had died after falling down her cellar stairs.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Henry Carrier and Sons, lacemakers … the firm

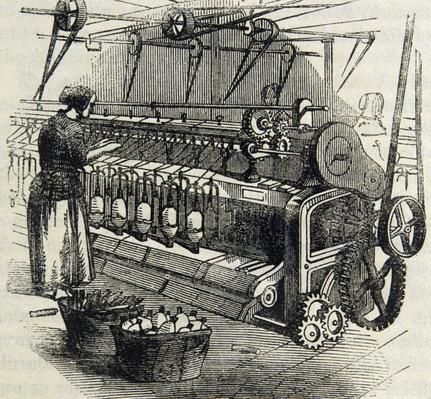

Adeline has a lot of information about this firm, via her father’s connections …. “In 1857 Henry Carrier & Sons added a wing to their old lace factory in Bath Street, built an engine house, equipped the whole factory with shafting and installed stocking frames in the new part.

Men and their families came from Basford and district to work the new frames. Their names were Anthony, Benniston, Kirk and Whites, and by degrees the old stockingers were taken into the factory”.

“Many women and girls were employed in seaming the hose, for where it had only been possible to make a single stocking on the old frame, on the new ones dozens could be turned out. The price of stockings went down, as the output was up, and soon a very poor quality was on the market.

“The old-time stocking was made with good material and workmanship, but the steam worked frames, in many instances failed to give a satisfactory article to the wearer.

“This business has ceased to exist, and the premises are used by H. Carrier & Sons.”

Speaking before the House of Commons Select Committee on Railway Bills in 1866, Joseph Carrier described the firm’s movement of its goods.

“All our lace and hosiery goes to Nottingham, and the business connected with that has to be transacted by going to Nottingham….My brother employs a great many people. We have a greater weight of stuff than Mr. Ball; we make three or four times the quantity that he does; ours is a heavy material – we send tons a week to Nottingham. We send our manufactured stuff to Nottingham by the carriers and by our own conveyances. By rail we send hosiery in the rough, and it is finished in Nottingham. We pay 6d per bag by the carrier; what it is by train I am not quite sure; it would be something like 1s by an ordinary passenger train. We send a very small portion by rail when the carrier is gone; we do not make a rule of sending it by rail on account of the circuitous route and the expense”.

In June 1877 the partnership of Henry Carrier, Frederick William Goddard and Thomas Cutler of Nottingham and Ilkeston, trading as ‘Henry Carrier & Sons’, was dissolved.

In 1896 the Mount Pleasant factory in Mount Pleasant Yard, Nottingham — standing back some distance from Mount Street and hidden by the houses in Olive Row and Every Place –was 16 windows long, three stories in height in one part, though a fourth storey had been added over the majority of the building. It employed between 40 and 50 hands, mainly women, and acted as the firm’s warehouse and saleroom, the main factory being at Ilkeston. At that time the principal partners in the firm were William Henry Carrier (eldest son of Bath Street draper Joseph and Jane) and Samuel Cresswell. The latter – also a one-time pupil teacher at the British School in Bath Street — was the son of boot and shoe maker George and Eliza (nee Skevington) and had married Martha Howard in 1865. The couple then moved to Nottingham and thence to Sandiacre. At one point in her letters Adeline describes him as “a senior employee of Henry Carrier & Sons, of Bath Street, Ilkeston and Nottingham”.

On Thursday morning, May 28th of that year fire broke out in the finishing room of the factory, spread over the rest of the premises and destroyed most of it and its stock. The fire was so intense that glass in the windows melted and fell in droplets onto the ground. A local resident had been the first to discover the fire and raised the alarm, so that the City Fire Brigade with two steamers was quickly at the scene. The combustible nature of the factory’s contents meant that it was impossible to stop the flames from gutting the building, though the Brigade did prevent neighbouring premises being affected. Damage to the factory and its contents was estimated at £8000 – £10,000.

Sam was last seen on the previous evening by the porter who was locking up the premises; he appeared to be leaving and had disappeared by the time the gaslights had been turned out. However after the fire was extinguished, Sam’s badly burned and scarred body was discovered by two police constables as they searched in the upper storey. His body was in a sitting position against a counter in the making-up room, under a pile of coats. There were extensive cuts on his left arm and wrist, and a small knife discovered by the body, leading to speculation of suicide.

At that time Samuel and his family were living at the Chestnuts on Derby Road, Sandiacre. And at the inquest into his death, held on May 29th, it was revealed that his twenty-year-old son, George Howard, had left his father at the factory, expecting the latter to return home later, by train, as he usually did. Instead Sam appears to have secreted himself inside the building, until it was locked and empty, and then tried to commit suicide. He had been ‘depressed and morbid‘ for several months though no-one had known why; he had been frequently heard to wish he could draw an end to his life. However the doctor who had examined the body pointed out that the cuts on the arm and wrist were superficial, and that the heart and lungs pointed to a death through suffocation.

Thus, the inquest jury found that “death was caused by suffocation, produced by being in the burning building in which the deceased had secreted himself alone: that he had inflicted the wounds upon himself: and that he committed suicide whilst in an unsound state of mind”.

The origin of the fire remained a mystery.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

In 1939, the year of the Ilkeston factory’s closure, the Ilkeston Pioneer noted that 60 or 70 years before, the factory’s whistle would proclaim the time to a large number of the town’s residents. ….

“When there was a doubt as to the time it was not an unusual question – Has Carriers gone? – or to be told – There’s Carriers”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Lace and stocking making

Family history and connections would help Adeline to be well-informed about this industry.

“Ilkeston in the early fifties of last century, was a small working-class Market Town with approximately three thousand inhabitants. There were no residential gentry. Its chief industries were lace and stocking making. The man who had a frame at his home and worked it himself was often in a very poor way”.

“The pay he received was not equal to the time occupied in making those single stockings, and he was very fortunate if he had a wife or daughter who could scam the stockings for him, as that was an extra expense. Certainly a few had more to live upon than others, but all had to work in some way or other. When trade was bad the poorest had a very lean time, and had to have assistance from the parish. At that time the parish pay – now called the dole – and the loaves of bread were distributed at the old Cricket Ground Chapel on Thursday mornings. Rents were low, and so were the wages, but people in those days were more easily satisfied with what they earned, also with what their money could purchase for them. There were no amusements, fashions were simple, foodstuffs restricted in number, and home life was looked upon as the chief thing.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

We will now examine the premises of the Carrier family in both Bath Street and East Street.