We walk on from the residence of Enoch Carrier and consider what Ilkeston’s housing for the “working classes” was like at the time of Adeline’s birth.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Crowded House

On February 20th 1852 the Nottingham Review (and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties) attempted this assessment of this housing …

“The buildings, generally speaking, especially the houses, are mean and very inconvenient. A stranger on entering one of them would at once conclude that the aborigines, or primitive natives of the place, must have been a race of dwarfs, the antipodes of what many of them now are. Be this as it may, they look, from their grotesque and irregular appearance, as if they had dropped at random from the clouds, and proclaim a state of mediæval civilization altogether incompatible with the architectural improvements of the present age; and it is a matter of wonder, that the respectable and well-to-do middle classes here, of which of late years a large number have sprung up, do not set about building houses in the modern style of architecture, with its infinitely superior neatness and accommodation.

“Recently, it is true, the example of erecting buildings of the kind just alluded to has been partially set by a few of the spirited inhabitants, but as yet their laudable example has not been followed by others. We happen to know that if a score or two of such houses were built in the principal thoroughfares they would not remain a day untenanted…”

In her letters Adeline adds supporting detail … “Most of the cottages were small and inconvenient, having a tiny living room and a parlour, with two bedrooms over them. Some cottages had only a living room, with bedroom over, which was often divided, the first room being open to the stairs. Sometimes there would be five or six children in these small dwellings but very few people complained about the smallness or inconvenience as they had got accustomed to them”.

Washing days

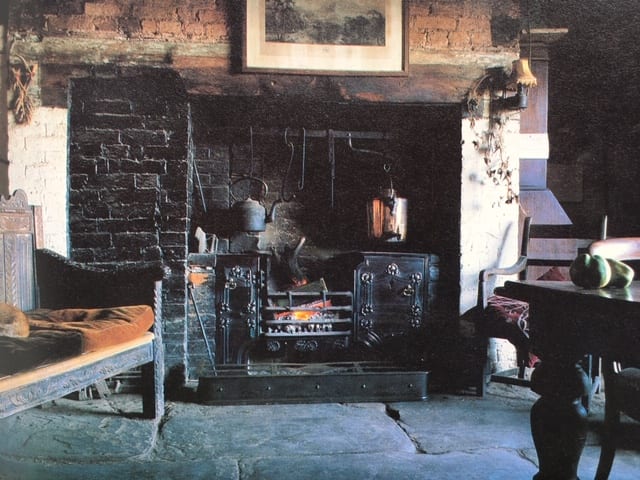

There were no sculleries or coppers, all the boiling of the clothes had to be done over the living-room fire.

There was a bar over the fire that held a ratchet hook, and the large boiling pan had to be lifted on and off the hook, a very trying and dangerous business for the wife and mother.

Cooking

There were no gas or electric cookers, all cooking had to be done either over the fire or in the small side oven.

Some of the very old houses had only hobs either side of the grate.

An iron stand with hooks had to be hung on the bars and a dripping pan or a Dutch oven had to be used for cooking meat.

So it may be imagined that under these conditions life in a small house with several children, was not a bed of roses for the wife and mother.

Bathing

There were no bathrooms or baths.

For small children a wooden washing tub was used.

Older children and adults used the dolly tub.

It was a common thing to see the dolly tub in the collier’s house.

It was necessary for the man or boy to have a thorough wash when he returned home from his work in the pit.

Bed time

There were no foot warmers or hot water bottles.

If a bed required warming the warming pan had a few hot cokes shaken into it, and then the pan was moved inside the bed to warm it.

But great care had to be taken, as the sheets were liable to get scorched.

“Of course rents were very low in those early days and so were wages. It was wonderful how the people lived, paid their way, and brought up large families. It was a desperate struggle, but it was done, and some of those poor colliers and their wives, out of their meagre earnings saved, and had a cottage built for themselves. Some men were fortunate in becoming butty colliers; these had men working under them, and earned a comfortable living. A very few became contractors and pit sinkers. One contractor that I knew personally, at his death left £30,000. This I know was a great exception. A few left small fortunes but the majority had to work hard to keep a roof over their heads, and provide enough food for the family. Some of the wives would go out to work , washing and cleaning; for this they would receive one shilling, and their food, for a day of ten or eleven hours, so the working class had not much leisure for amusements even if there had been any”.

“Today things are very different. The small, uncomfortable cottages are giving way to up-to-date houses, where the wife and mother has the advantage of modern times”.

At the beginning of 1853, the Pioneer reported an inspection of the town organised by the Sanitary Committee to root out everything that was ‘foul and offensive’. One of the appointed inspectors described a visit which he had made to a house in Moors-bridge Lane (Derby Road). He politely knocked at the door but as no-one answered he felt able to enter the house. The first room was empty but in the parlour he found a pair of donkeys ‘quietly browsing in the corner, safely sheltered from the pitiless storm and plentifully supplied with fodder by their humane owner!’

“Another resident always kept ‘the fatted calf’ in his bedroom, but could not tell whether the poor innocent was what is considered good company for a bedroom”.

A couple of months later and the same newspaper was not very impressed with the ‘work’ of this newly-formed Sanitary Committee … where are the Scavengers, appointed to clear up the streets ?? ‘Nowhere to be seen !!’ was the answer.

And what about the ankle-deep soft sludge which ‘decorates’ the boots of anyone who dares walk through the town … why, it is still where it always was, lying undisturbed in the public streets !!

————————————————————————————————————————————-

The years passed but was there any improvement?

In 1861 an editorial in the Pioneer took stock of the housing of Ilkeston’s labouring poor which it described as the “monster evil of our times”…..three, four or more families in one house; often one family per room; parents, grown-up children and a ‘lodger’ perhaps sleep in the same area; “no provision for the ordinary decencies of life”. Disease and immorality were all around the folk of Ilkeston. As the nation grew, as industry flourished, as the population expanded, the problem worsened and the Pioneer saw no quick solution. It did however call upon landlords to provide decent homes with “adequate provision for the moralities of life”.

One such landlord whom the Pioneer had in its sights was Ilkeston builder Thomas Shaw.

Thomas Shaw and Pigsty Park

Adeline tells us ….“The upper field was turned into building plots, but it was not very attractive, in fact the road was so bad that one member of the Local Board said that the road was worse than a pigsty. The name caught on, and for many years that part of the town was called ‘Pigsty Park.’”

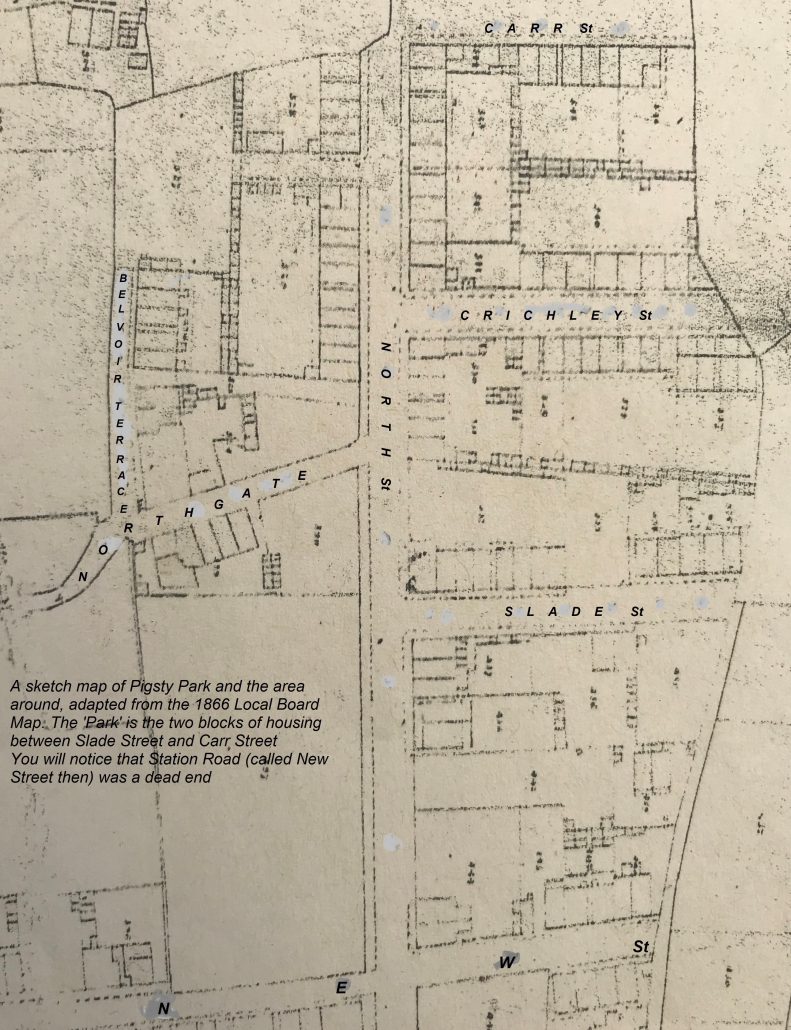

Pigsty or Pigstye Park was the district including part of North Street, Crichley (or Critchley) Street and Carr Street, about an acre and a half in area. The name seems to have originated about 1860, when it featured in the Ilkeston Pioneer of that time. The district is listed in the 1861 census, one of its residents being Thomas Shaw, builder and Primitive Methodist preacher, who designed and erected several houses in the area, on land he had purchased from Joseph Bailey, lace manufacturer. They were built in about six months.

In 1861 the Pioneer reported on a fatal fever raging through this area, resulting in four or five deaths, and put the blame for these squarely on the shoulders of Thomas Shaw. In its pages the newspaper accused the builder of cramming together his houses around confined yards, squeezing out any pure air and providing totally inadequate privies and drainage. This ‘sinkhole of the parish’ was a den of filth and fever, built purely for profit and without any regard for the health or safety of those forced to live there.

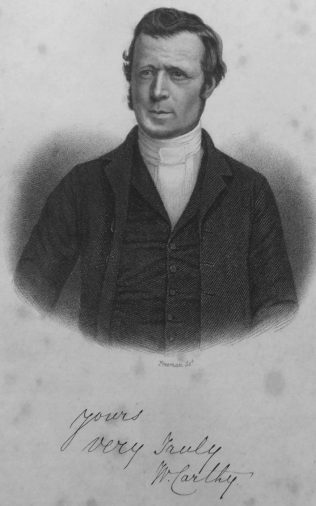

One of the victims of the Pigsty Park fever was the Rev. William Carthy (left) of the Primitive Methodist Chapel who lived in Carr Street and who died there of typhoid in October 1861.

Not unsurprisingly builder Thomas did not share the views of the Pioneer and stated that William Campbell, surgeon of this parish and Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, had inspected the houses and declared them ‘thoroughly healthy and commodious’. The fever was of a mild type and of the five or six fatal cases, most of the victims were either weak or ‘uncleanly in habits’.

The Pioneer remained unrepentant and a little a later was glad to learn that Mr. Shaw had given orders for the removal of all nuisances in the neighbourhood, the cleaning of yards, the whitewashing of houses, etc. The satisfaction felt by the newspaper was premature however for within six months Pioneer editor John Wombell was in court as a result of the ‘Pigstye Park‘ articles, defending himself against a case of libel brought by Thomas who was seeking £1000 damages.

Even before the appearance of the Pioneer articles Thomas Shaw and John Wombell were not the best of pals. Thomas was a prominent and active member of the Primitive Methodist Chapel, a teacher and preacher. John was an erstwhile member of the same chapel but had been expelled in 1851 and Thomas had played a prominent part in his expulsion. (See John Wombell and The Ilkeston Pioneer).

The Ilkeston Leader and Erewash Valley Advertiser — a rival to the Pioneer — no doubt felt a public duty to report extensively on the evidence given at the subsequent trial of John Wombell. Some interesting detail about the housing emerged.

Thomas had bought the land for £700. The streets were of iron stone cinders.

The houses had four to six well-lighted rooms described as 10 feet by 11 feet, some larger, with height eight feet to 10 feet, each with a garden of 60 to 70 square yards and with a ‘necessary’ at the end of each, with a few exceptions.

There were ‘panty-pits’ or small cesspools, one for every two or three houses, at the rear of the properties, to ‘take the swilling and washing away from the doors’ and which drained out to an old town water course. These pits were generally kept well apart from the property water sources.

About a dozen soft water cisterns were erected in the area supplying washing water, while a well, 15 yards deep was sunk to supply hard water. There were three main drains with pipes from each property leading to them, while surface rain water was carried away efficiently by the drainage provided.

The houses had been let well at 2s 7d per week but since the articles in the Pioneer several of them had been empty.

These details were supplied in court by Thomas Shaw whose evidence was supported by others, including surgeon William Campbell, lace manufacturer Joseph Bailey, grocer and Highway Board overseer Luke Wright, chairman of the Highway Board Henry Ash, coalminer and occasional pit- and well-sinker James Trueman, sanitary pipe manufacturer Richard Evans, joiner and resident of Pigsty Park Thomas Bancroft, and George Bridgart, surveyor for the County of Derby. The latter concluded by stating that he had not seen so good property of its class either in Nottingham or Derby.

This weight of opinion may have overwhelmed editor John for he declined to produce any witnesses or contradict any of the previous testimony. On the contrary he was now willing to concede the case, pay 40s damages plus costs of about £130, and withdraw ‘all offensive observations contained in the libels’. Magnanimous Thomas accepted this offer, declaring that his character and property had been vindicated, though the name attached to the area continued in use for several more years.

It might be noted that the Pioneer’s account of the trial and evidence was much more concise, stating that the trial had been brought to a premature conclusion after an ‘understanding’ had been reached between plaintiff and defendant, but that Mr. Wombell had been prepared to put forward a stout defence with supporting evidence.

Unfortunately for Thomas, the newspaper proprietor was declared bankrupt later in 1862 so that he could not pay the majority of his fine or costs. Thomas Hives of the Rutland Inn and druggist George Purcell of Bath Street had acted as guarantors of payment however and so Tom the Builder now pursued the pair for payment. The innkeeper paid his portion of the outstanding account but another ‘misfortune’ now befell the builder when he discovered that druggist George had become an inmate of the county lunatic asylum at Mickleover and was in no position or state of mind to settle his affairs.

In 1864 Thomas Shaw suffered an unfortunate accident when building some fixtures onto a stable. He ordered one of his workmen to knock off a piece of iron from some woodwork which the man did, only to see the detached metal fly into Thomas’s eye and literally gouge it out. Dr. Norman was quickly in attendance but the sight was too severely damaged for Thomas to recover its use.

In 1866 the Local Board noted that John Wheatley had built eight houses at Cotmanhay and had provided only one privy; the Board instructed him to build at least one privy for every two houses.

In the Summer of 1868 the issue of the water supply in this area was raised when the residents of North Street addressed a petition to the Waterworks Company requesting that the company extend its mains to their houses here. Similar problems were also serious in Kensington and Cotmanhay. Many inhabitants had to fetch water from either the canal or the River Erewash, a distance of up to a quarter of a mile. The Company agreed to comply with the request wherever possible and as speedily as it could. At the same time and exercising its powers, the Local Board required property owners to lay on a water supply to their houses “wherever the mains of the Waterworks Company can be brought sufficiently near thereto”.

In 1870 Thomas Shaw was declared bankrupt.

In 1874, when investigating the future sewage disposal requirements of the town, the Local Board found that raw sewage from houses in the Station Road area was flowing out of pipes into an open ditch and thence to the river Erewash. There was a considerable amount of solid matter and the outfall had discoloured the water, making it thick and nasty and creating an offensive smell…. well beyond this area.

In 1881 Dr. Robert Wood was serving as medical officer for the Local Board to which he reported regularly. In August 1881 he felt obliged to complain of several cases of overcrowding in the town. In Cotmanhay he had found a premises, inhabited by the Dilks household, of two rooms accommodating nine persons — ‘unhealthy and immoral’. Another, in the same area housed seven inhabitants. And in Awsworth Road, Thomas Meakin’s family of six, plus two boarders, was living in positive and overcrowded filth.

Here we are (above) in the 1970s, standing in North Street, looking down the length of Carr Street, eastwards towards Mill Street. (Jim Beardsley Collection)

Thomas Shaw had married Ann Corbett on December 26th, 1845 at the Parish Church of Ashby de la Zouch, when he was described as a “Primitive Methodist preacher”.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

But before we walk on …. from the personal collection of Jim Beardsley

about 150 years after Thomas Shaw built his ‘Pigsty Park’, a street in that area … showing the typical terraced houses of that time and found in many neighbouring streets … North Street, Wood Street, King Street, Chapel Street, John Street, Mill Street, and on and on.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

————————————————————————————————————————————-

At this point we can pause and consider some of the specific building projects which took place in Victorian Ilkeston (1837-1901)