Samuel Whitehead, hero of Waterloo had connections with the Ilkeston Baths.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Where were the Baths ?

Not too confidently (and incorrectly) Adeline declares that “in 1844 or thereabouts a warm mineral spring was discovered at the side of the Rutland Arms, and this was expected to become a great asset to Ilkeston”.

In an earlier Advertiser article of 1933 Adeline included more accurate dates as she mentioned that the discovery of the ‘alkaline mineral spring’ was about 1830.

“A Bath House was built, the grounds laid out, even the street which up to this time had been called the ‘Town Street’, had the honour of having it changed to Bath Street. The Rutland Arms was rebuilt and enlarged, and all was in readiness for the great number of visitors that were expected to take advantage of Ilkeston’s noted waters.”

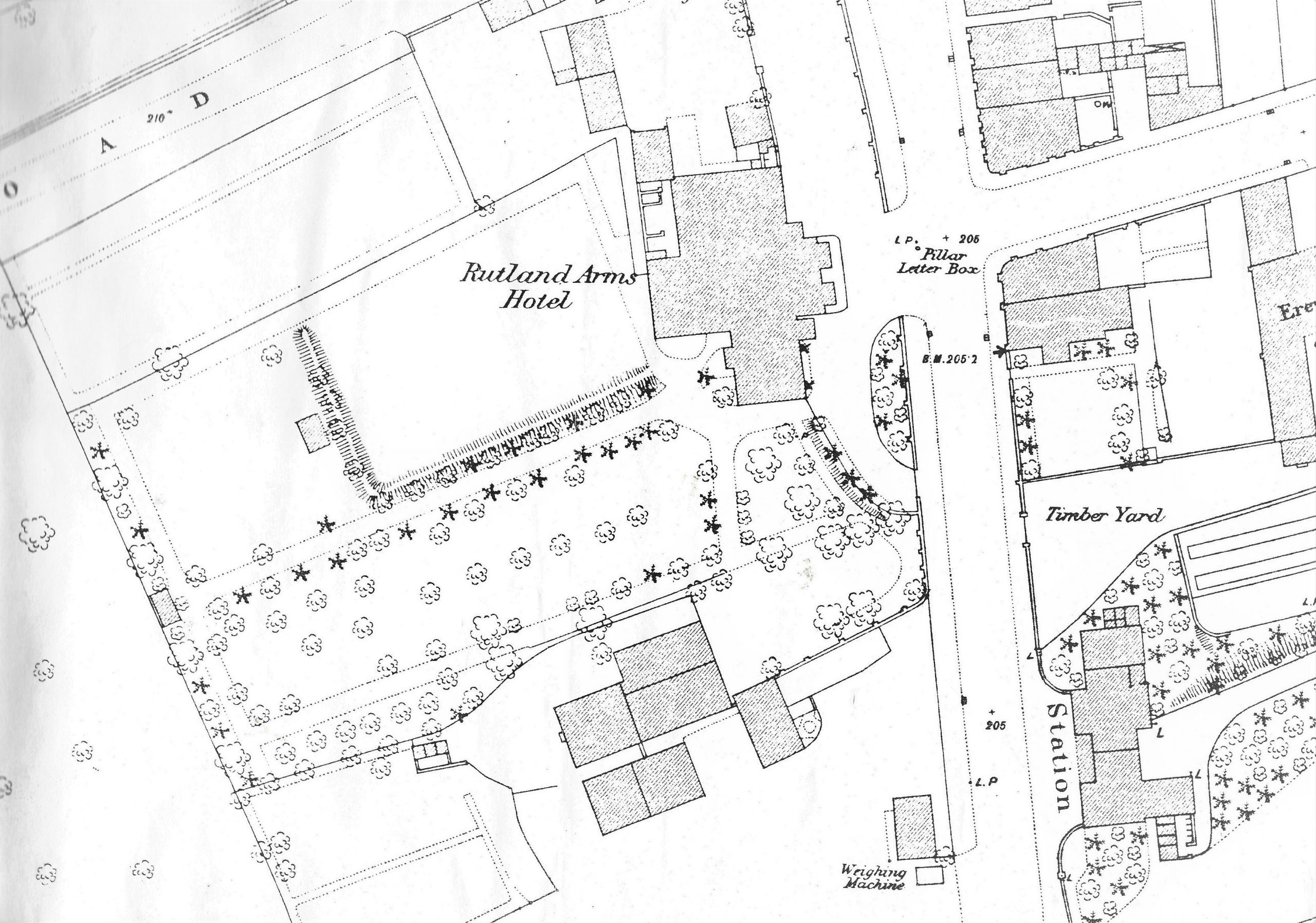

Above, Ilkeston Baths in 1866, and below in 1881

The Baths were built on the west side of Bath Street, opposite the Town Railway Station, and lying south of the Rutland Arms, separated from the latter by the ornamental Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. They were east of Ilkeston Old Hall or Manor House, standing at the corner of Bath Street and (what was later) Manners Road.

Comparing the two maps above, the only significant difference is the disappearance of the railway lines serving the Rutand Collieries (seen at the bottom of the 1866 map).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

1829; the birth of the Baths

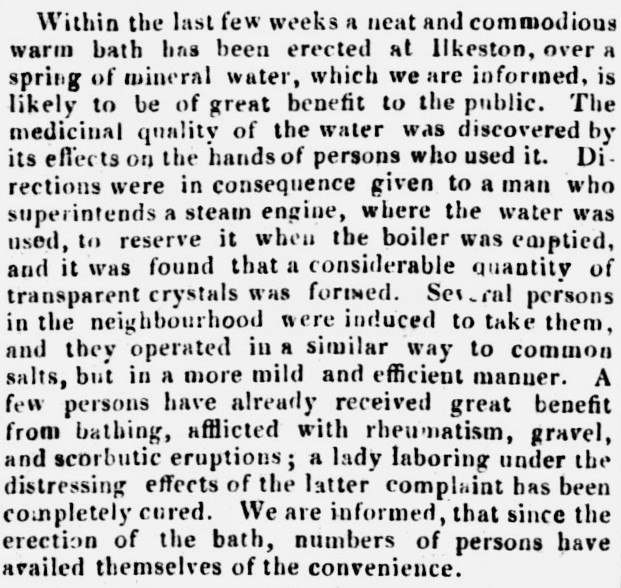

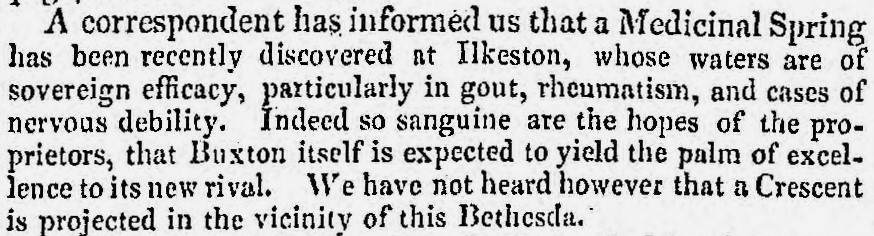

In October 1829 the Derby Mercury was alerted to the recent discovery of a ‘Medicinal Spring’ at Ilkeston and its powers to conquer gout, rheumatism and nervous debility.

Derby Mercury (October 21st, 1829)

The Spring’s owners were brothers Samuel and Thomas Potter and were hopeful that Buxton itself would ‘yield the palm of excellence to its new rival’. When the Mercury mischievously added that ‘we have not heard however that a Crescent is projected in the vicinity of this Bethesda’ it was probably making reference to the Pool of Bethesda, mentioned in the Gospel of John, supposed by some sources to have healing properties. Almost simultaneously, it was reported that building had been afoot at the site and the genesis of ‘Ilkeston Baths‘ could be seen. A letter-writer to the Nottingham and Newark Mercury (December 26th, 1829) reported that a building had been put up by about August of that year.

Nottingham Review and General Advertiser (October 30th, 1829)

It appears that prior to 1829 coal mining at the Rutland Colliery was being hampered by the influx of water at the pits.

Late in the 18th century, miners at the workings were experiencing discomfort in the water which ‘smelt like gunpowder‘ and after being immersed in this water, their hands emerged looking ‘like those of washerwomen’. A steam engine had been built at the colliery to help pump out the water and about 1829 a small water reservoir was erected nearby to collect this water — which then supplied the engine as well as providing a basic hot bath for anyone who wished to use it.

“The first day the bath was filled, all who chose were permitted to make use of it gratuitously, and forty-six persons enjoyed a refreshing emersion”.

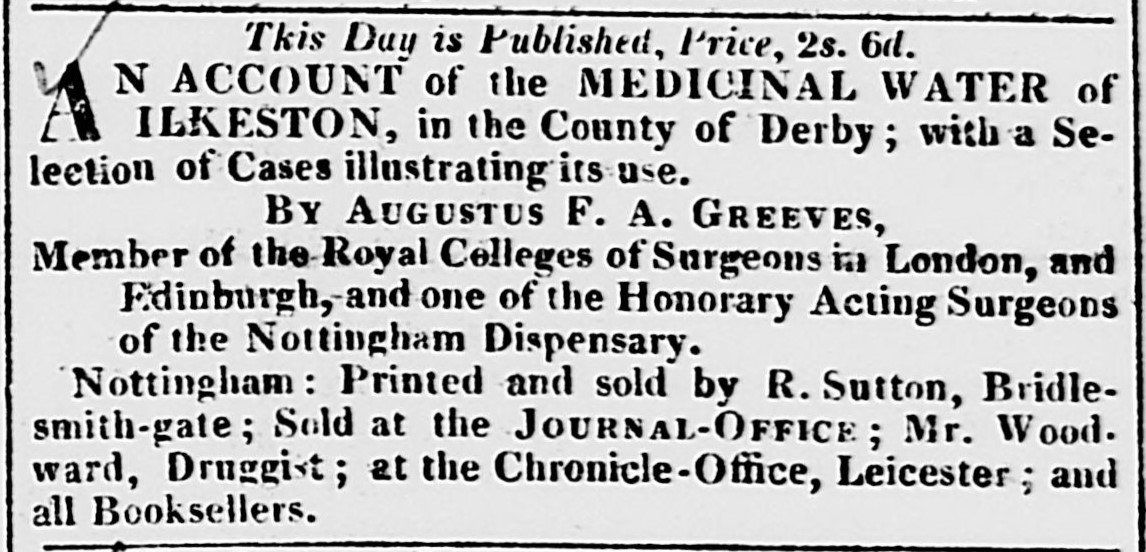

Thus wrote Augustus Frederick Adolphus Greeves (M.R.C.S), a visiting honorary acting surgeon of the Nottingham Dispensary, who recorded all of this in ‘An account of the Medicinal Water of Ilkeston’ published in 1833.

By December of 1829 the water had had its preliminary examination by “Dr. Murray“. And so, on Christmas Day, the Nottingham Review was ready to issue a detailed assessment of Ilkeston’s new attraction. Sufferers from rheumatism, pains in the head, chest and bones, catarrh, gravel, contusions from falls, wounds and scurvey had all found relief in bathing in the waters. And a dose of the water, concentrated by boiling, was effective at treating scorbutic eruptions and heart-burn, as well as acting as a purgative medicine. And it tasted good, as well !!! And if boiled even more, the salts left by this process could be used to heal burns. The new Bath House, with a dressing room attached, was nine feet by seven feet, and four and a half feet deep; the water tempearature could be varied between 55ºF and 135ºF, the hot water being heated by steam. And already, it seemed, local premises were catering for the visitors who were expected to arrive in growing numbers.

Subsequently numerous eminent analysts and surgeons — such as Dr. Fyfe of Edinburgh, Dr. Calvert of Derby, and Mr. Greeves — examined the water thoroughly and pronounced it almost unique, safe to use both externally and internally, and a possible treatment for all manner of ills

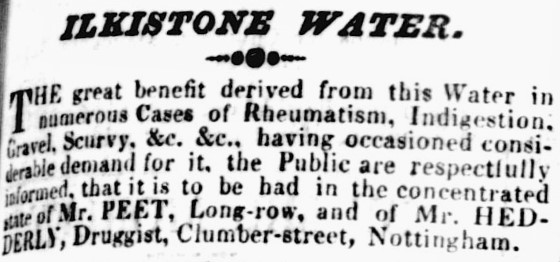

Soon after, people who had made use of it began to speak of marvellous cures. The Spring’s owners naturally advertised these commendations and the ‘concentrated water’ went on sale in Derby, Belper, Bakewell, Ockbrook and Nottingham, as well as at the Baths themselves.

As a result “the number of visitors increased so rapidly that the original bath was inadequate for their acc and ommodation, and the lessees were induced to erect the present neat and convenient edifice”. By March of 1830 over 200 visitors were expected for that month and the Potter brothers were planning to erect several new private baths. Thus it was that Ilkeston Baths were built by Messrs Potter, local property and colliery owners.

1830-1832; The Baths’ early growth

In his History of Ilkeston (1831) Stephen Glover records the year of the building of the baths as 1831 although he could be referring to an enlarged and extended version.

Nottingham Review (April 9th, 1830)

In April 1830 the Derby Mercury was now reporting the continued success of these mineral waters such that several new Baths were being built, some with suitable apartments. And in that same month the Nottingham Journal and others were explaining to prospective visitors from that city how they could travel to their Derbyshire neighbour …. “The Ilkeston Speculator Coach will on Monday 3rd of May commence running on Mondays as well as Wednesdays and Saturdays, to and from the Derby Arms, Nottingham, starting at the usual time”.

Nottingham and Newark Mercury (April 24th, 1830)

Nottingham and Newark Mercury (April 24th, 1830)

In late June and into July of 1830, 1250 names were added to the ‘membership’ books of the Baths. Perhaps this was because, in June 1830, “new slipper baths, with separate apartments for ladies’ were opened, and coming very shortly…shower and vapour baths”. While the concentrated water was now being widely sold and putting Ilkeston “on the map” !! Half a pint to a pint daily of the natural water was “found very useful in scrofula, indigestion, various afflictions of the liver, gravel, gout, and many kinds of eruptions of the skin”.

If this water was partially boiled off to provide a more concentrated form, then it could act as “a mild and active antacid aperient.” And “in case of piles, obstructions of the bowels, worms, protracted cases of spasms of the stomach and bowels, headaches from disordered stomach, and some varieties of jaundice” it was also most useful.

External use was also of benefit. “The hot bath, for the employment of which the spirited proprietors have erected every convenience, is serviceable in rheumatism, paralysis, gout, and in most of the diseases in which the internal use of the water is beneficial”.

It’s a pity that King George IV wasn’t aware of the miraculous qualities of the Ilkeston Springs. He died in June 1830, after several years of ill health and some months of intense suffering. Who knows what a steady supply of ‘Ilsun’ water might have achieved for him or how the course of history might have changed had he got his hands on a few bottles of Ilkeston’s ‘elixir’? — instead of the copious quantity of alcohol he consumed?

One who did benefit however was Ilkeston schoolmaster ‘Billy’ Pitt of Bath Street, a very long-term sufferer of ‘paralysis’ and a regular inmate of Manchester and Liverpool Infirmaries — where he had been ‘electrified’ and ‘galvanised’’, purified and no doubt petrified, without any discernible relief from his suffering. Yet, four bathing sessions at the Ilkeston Springs resulted in him being able to walk briskly without a stick, write his own name, and “take up a brick 7 or 8lbs in weight, and throw it over his head to a considerable distance, with the hand, which a fortnight or three weeks ago was perfectly useless”.

Billy died in March 1862, aged 73, though in the last few years of his life he suffered from hemiplegia (paralysis of part of the body).

Several other prominent Ilkestonians also took the ‘Ilkeston Waters’ and found relief from lumbago, gravel, scurvy, indigestion, rheumatism, debility, gout, piles and a scalded face, as proprietor Thomas Potter (who but?!!) could testify.

The popularity of the Baths continued to grow. In April 1831, annual subscriptions were now available for the ‘Old Bath’, costing £1, over 30% cheaper than attendance at ’Ilkeston Baths’ which cost £1 10s– the latter included use of Hot, Cold, Shower and Vapour Baths, and the drinking of the water. Family tickets could also be purchased (though they didn’t include servants). Even the Duke of Rutland had bought a ticket and the Water was now available in Mansfield, Sheffield and Manchester.

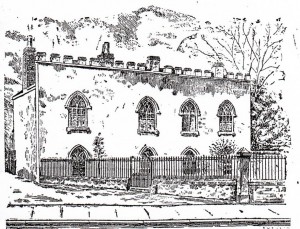

Ilkeston Baths as they appear in the Ilkeston Advertiser, April 22nd 1899.

Glover described the Baths as a building “of gothic architecture, in the cottage style, but built in several stages.. ..designed, it is believed, by Mr. Thomas Potter. The ladies’ and gentlemen’s baths and changing rooms are neatly fitted up, with showers, and hot and cold baths. The baths are of Mansfield stone; they are supplied through pipes, with hot and cold water, as may be required by the patient; every bather having the advantage of a fresh supply of water from the reservoirs or cisterns, which are constantly replenished from the pumps of a steam engine”.

The waters of the Baths, applied externally or taken internally, were curing or relieving rheumatism, lumbago, paralysis, scrofula, sciatica, scurvy, gout, gravel, indigestion, bladder stones, debility, leprosy………. !

The Leicester Chronicle (September 1831) also recommended ‘The Ilkeston Tooth Powder’, “a sediment from the Ilkeston Water, possessing its sanative properties, and an excellent remedy for scurvy in the gums”.

Derby Mercury (September 28th, 1831)

The Baths expansion then continued.

In summer 1832 the Derby Mercury advertised a newly constructed bath “for the accommodation of the higher classes of patients” with two dressing rooms, “to remedy the inconvenience heretofore experienced by gentry visiting for the day, who have frequently been obliged to wait for a long time, and in many instances to return home without having an opportunity of bathing”.

Similar in shape to the existing one this larger bath measured 12ft. by 9ft. and was 5ft. deep, though it could be made shallower to suit children.

And Leicester, Loughborough and Belvoir had been added to the list of centres offering sale of the Water.

The Baths’ cure-all benefits: 1832-1848

Samuel Whitehead, the ‘Hero of Waterloo’, served as the first manager of the Baths and in 1832 felt himself close to death, suffering constant pains over his whole body, diarrhoea and sickness, such that he could hardly walk. He feared that he might have been struck by cholera which had broken out in the northeast of England at the end of the previous year and was now spreading. It was natural that he should try a dose of ’Ilkeston Water’. Within a few minutes the pain in his bowels disappeared and within a few hours he was free of all aches and pains.

1832 was the year of Samuel’s marriage and surely had nothing to do with the way he was feeling??

The Ilkeston Waters were seemingly of benefit to him. As we have seen he died in 1870, aged 92.

An outbreak of cholera at Ilkeston prompted this notice, dated May 6th 1833, from Mr. Thomas Potter…

“The poor of Ilkeston, who are unable to pay for medicine or medical attendance, are….informed that, should any of them be attacked with sickness, pains in the bowels, diarrhoea, or spasmodic affections, the usual fore-runner of cholera, Mr. Whitehead would, on application to him at the baths, furnish them, gratis, with a proper quantity of the concentrated Ilkeston water, which in such cases, had been very successful”.

The Ilkeston Water came under very close scrutiny …

Leicester Journal (August 2nd, 1833)

Leicester Journal (August 2nd, 1833)

According to Augustus Greeves, in his pamphlet, in five weeks 70 applicants took advantage of Thomas Potter’s offer, to drink the water andsave themselves from Cholera. From these, only two fatal cases resulted and they were well advanced before the water was taken — so it was claimed.

“Mrs. Foster was in constant attendance to wait upon female visitors“. (LC.1838) This was Fanny Foster (nee Lacey), the wife of engine driver Joseph, who lived close by. Joseph died on January 28th, 1851, aged 66, by which time he had worked for Samuel Potter for 28 years.

And then, in May 1838, the Derby Mercury announced that Concentrated Ilkeston Water was now available in greater quantities — thanks to additional apparatus. Application of this liquid, either internally or externally, would help cure, scurvy, leprosy, scrofula, spasmodic affections, liver complaints, rheumatism, gravel, paralysis, gout.

In 1839 John Humber, the landlord of the Wheat Sheaf Inn at Loughborough, felt an ‘irresistible impulse’ to write to the Loughborough Telegraph, extolling the virtues of Ilkeston’s Baths.

He had been acquainted with Charles Simpson, glove manufacturer of Nottingham, who was suffering from chronic rheumatism, debilitated and wasted by pain, distorted by affliction, and his locomotion, ‘like a crab, sideways’.

After a few weeks’ use of the Baths, Charles was a new man, walking without pain, erect as a drill sergeant.

He was beside himself with gratitude.

“Previously I had been confined to my bed seven weeks. But now, (leaping as he spoke, with great glee, from his seat) see how I am. I am a miracle. In my sixty-sixth year, I shall this day walk to Nottingham”.

Does this remind you of the effect upon Uncle Albert — hobbling around at Peckham Market — when Del Boy demonstates his ‘revolutionary osteopaedic inframax deep-penetration massager’ on the rheumatic OAP? You can view it here — https://ne-np.facebook.com/OnlyFoolsLines/videos/the-inframax-deep-penetrating-massager/2358181270989614/

1848-1858: Baths under new management

By 1848 the condition of the Baths had been allowed to deteriorate, the premises becoming ‘delapidated’. At this point their management was taken over by Thomas Hives and quickly restored “to a comfortable state of repair” for both rich and poor. A new splendid wing was added to Hives’ Hotel, fit to receive any member of the nobility who wished to wished to stay there. It seems that at this time the name of “Rutland Arms Inn and Railway Hotel” was adopted by Thomas, as was the crest of the Duke of Rutland.

On Whit Thursday of 1849 Thomas Hives opened the Bath Tea-Gardens. While 100 guests sat down to enjoy tea, the Ilkeston Brass Band entertained them. This was followed by dancing on the spacious lawns, as the audience swelled to over 2000 (or so it was estimated). The evening drew on and the occasion was brought to a conclusion by a fireworks display, courtesy of James Chadwick, a balloon extravaganza and a magic lantern display. “Not a single plant was injured, nor was any indecorum observed“.

And in June 1851 the Derby Mercury noted that …..

“the spirited proprietor (ie Thomas Hives) of the Vauxhall Baths has made considerable ornamental additions to his grounds, after the style of the celebrated Rosherville Gardens, of Gravesend, which call forth the admiration of numerous visitors”.

Ilkeston Baths as they appear in the Ilkeston Pioneer of June 1853.

In 1854 Venerable Whitehead described the Baths thus; …..

“next to its church, this is one of the architectural glories of Ilkeston – one of the wonders too”.

He then pondered on the locals’ appreciation of them.

“I cannot… descant on the marvellous cures these waters have effected — but I can appreciate the comfort and advantage the Baths offer to Ilkestonians and to visitors. Are they used as such privileges should be? Do all avail themselves of the luxury and health these Baths offer?

“The Pagan Romans so loved their baths that, even in this clime, they never dispensed with their daily ablutions.

Christian men and women should use them oftener…. I wonder how many of the black diamond delvers come hither for a wash on a Saturday night? …

“I conclude that there are special baths for this class and for other sons of toil”.

In the same year a dose of Concentrated spa water was claimed to ….

“modify and improve the biliary secretion, producing more alvine evacuations, and increasing very perceptively the secretion of urine.

“As an aperient it is very useful in those torpid conditions of the bowels depending on an inactive state of the liver, too frequently the result of sedentary occupations or studious habits.

“It is a safe and efficient remedy in piles, and all obstructions of the bowels, particularly when combined with an alteration of the bile……Sold in bottles, 1s each”.

I could provide a translation but I think you get the gist?

In late 1853, when a cholera epidemic once more threatened, the inhabitants of Ilkeston were blessed with detailed advice on how to treat it from ‘Progress’ via the letter page of the Pioneer. He prescribed a tablespoon of best mustard in cold water to facilitate vomiting, followed quickly by 10 grains of cayenne pepper in a wine-glass of brandy … the usual result ? .. immediate relief followed by rest, perspiration and sleep. ‘Progress’ admitted that he had lifted the recipe from the Times, and that it had been prescribed by Edward William Lane, ‘well-known Eastern traveller’.

While the Pioneer felt this worthy of publication it covered its back by drawing upon the Treatise on Ilkeston water written by Amos Beardsley (see below) when the author wrote, reassuringly, ….

“In cholera, the concentrated water was administered in the epidemic of 1832, and with decidedly beneficial results — many cases were alleviated and arrested by its use. Saline medicines have had, and still retain their share of confidence. From the property this water possesses of provoking both the secretions of urine aand bile; and as those two secretions appear to be completely suppressed in cholera, there is great probability that its administration in this disease, would prove useful: for whatever remedy is proposed — amendment is to be dated from the time when the functions of these two organs (liver and kidney) become reinstated”. (IP Oct 1853)

At the end of June 1855 the Ilkeston News noted that the Baths had been closed for some time — a lack of water !! However, by July the ‘mineral waters’ were once more open, and ready to reclaim their ‘world-wide fame’. At the same time the newspaper had a suggestion for the Proprietors — the charge for using the Baths was a little too high, especially for working people; “if they are to be pleasure Baths at all for that class of the Inhabitants, the charge should be reduced to the same rate as in large towns”.

And finally ….

If afflicted with gout or sharp rheumatic pain,

It may leave you sometimes, but soon comes again;

If disease of the spine, or gravel, or stone,

Or your sleep or your appetite from you have flown;

Oh, do not despair — there’s many can prove

These waters have caused all their pains to remove;

If you’re doubled with pain, and as thin as a lath,

Come at once, then, and try the Ilkeston Bath !

(IP June 1900)

1858 onwards; The Baths’ decline

Did Adeline have the advert from the Ilkeston Pioneer of June 1858 (right) when she wrote …. “in 1858, it was reported that the Alkaline Carbonated water had been recovered, so the buildings were restored and accommodation increased. Dr. A. Beardsley, of Cotmanhay, wrote a treatise* and the Baths were again advertised, but Ilkeston failed in its rivalry to become a Spa. The Baths were closed” ?

*The treatise was written by Amos Beardsley, surgeon and son of William, creator of Chain Row in Derby Road, and Ann (nee Sills).

Adeline speculated on the decline of the Baths …. “For a time it seemed likely that Ilkeston would eventually become a Spa – might even rival Bath and Buxton – but unfortunately for the Promoters of the scheme, the spring disappeared, owing, it was believed, to the workings that had been started in the neighbourhood”.

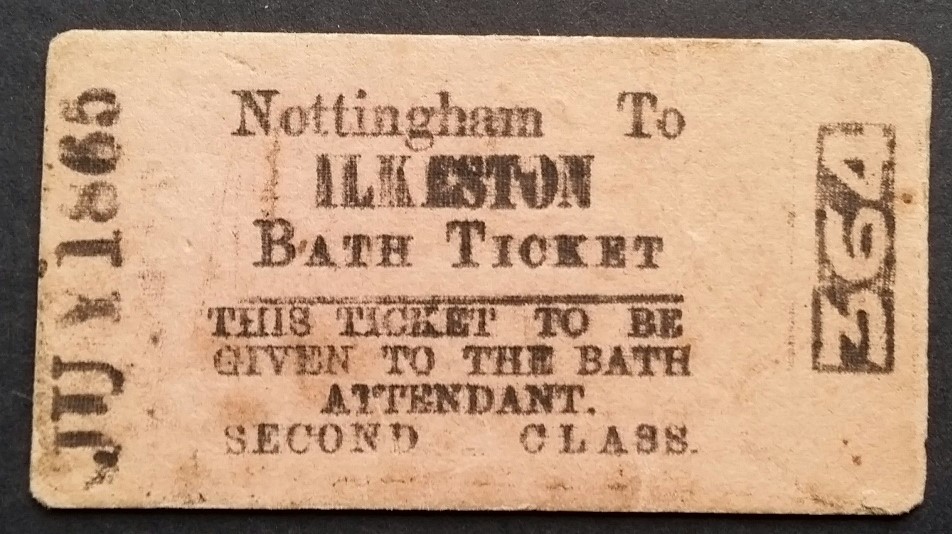

In the mid 1860’s trains were running from Nottingham and from Derby to bring visitors to the baths — fares included bath fees.

Courtesy of the Andrew Knighton collection

One man who was visiting Ilkeston in 1866 was retired draper Isaiah Cleminson who was pleasantly surprised to find that Thomas Hives had reopened the baths ‘on a new and better principle’. He had originally intended to visit a few friends in the town before travelling to Smedley’s Hydro in Matlock Bath for the sake of his health. However whilst in Ilkeston he learned that Thomas had hired a bathman previously employed at the Hydro … and on visiting the Bath Street premises Isaiah was suitably impressed; they were just as good as those in Matlock Bath. The waters in Ilkeston were unique such that Ilkestonians should value and use them more. Perhaps people went to Matlock because of perceived better scenery there — but how wrong they were; Ilkeston was surrounded by beautiful valleys and charming villages. (letter to IP)

This personal view was supported at the same time, in the same publication, by the proprietor of the Ilkeston spa — who else ?!?

Thomas Hives informed readers that Mr. W(illiam) Crowder and his wife (Esther), late of Wood Villa House and of Smedley’s Hydro, were now employed by him to administer Hydrotherapy Treatment to all persons suffering from disease of any kind, and under the superintendence of a Physician.

It was at this time that sea-bathing at coastal resorts was becoming fashionable, helped by the spread of, and improvements in, the railway system. …. and so ‘taking the waters’ was being regarded as out of date. In the 1850’s Skegness was a small village of less than 400 people. When the railway reached the town in 1873, working-class day trippers began arriving in large numbers — and many came from Ilkeston !!

Skegness Parade in the later 1800s

The Baths were demolished in 1899, and eventually on their site was built a row of four shops, fronting onto Bath Street at the corner with Manners Road, and a terrace of houses along the latter road, on its northern corner with Bath Street.

And here is one of the last pictures of the Bath Houses … from a Coronation Souvenir brochure of 1911.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Bath House Bostocks

Adeline writes that “after 1858 the Bath House became a private house, and was let to Mrs. Bostock.

The Bostock family which most closely resembles the one described by Adeline – with several discrepancies — is that of labourer Benjamin and Grace (nee Hutchinson), the daughter of Heanor Road cowkeeper Joseph and Catherine (nee Beardsley).

They had married in February 1831, lived at the bottom of Moors Bridge Lane and then in the Awsworth Road area, raising a family of at least seven children — and one dying in infancy.

The three oldest children had married and moved from home before the 1861 census locates the family at the bottom of Bath Street, close to the Rutland Arms.

Ten years later and the Bostocks are in Manor Road, the opposite side of the Rutland Arms to the Bath Houses.

According to Adeline “Mrs. Bostock, was a widow with two daughters, Ruth and Mary”.

Grace Bostock died in Manor Road in July 1872, aged 59. Her husband Benjamin was still very much alive and six months later married his second wife.

There were four daughters in the family … Elizabeth (born 1835), Caroline (1838), Catherine (1847) and Mary (1853)

“Ruth, the eldest, married Bob Henshaw, a miner, and lived in a small white-washed cottage, built on the bank on the East side of Bath Street. She died after a few years of married life”.

Daughter number 3 married miner Robert ‘Bob’ Henshaw in April 1866.

Only once, in the 1871 census, is she referred to as Ruth; in all other records she is Catherine (Bostock and then Henshaw), the name she was given shortly after her birth in 1847 and then buried with in July 1908.

“Mary, the youngest, was still at home”.

Born in 1853 Mary was the youngest daughter and stayed ‘at home’ until her marriage to tailor Stephen James Smith in 1877.

Six months after the death of his first wife, Benjamin Bostock married again, to Arnold-born widow Mary Langstreeth (nee Twells), daughter of glass manufacturer William and Mary Twells.

The Bostocks then moved to Mount Row, off Bath Street, with Mary’s son Alfred, from her first marriage. And Benjamin died there in February 1879, aged 72.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

and so to the Rutland Arms.