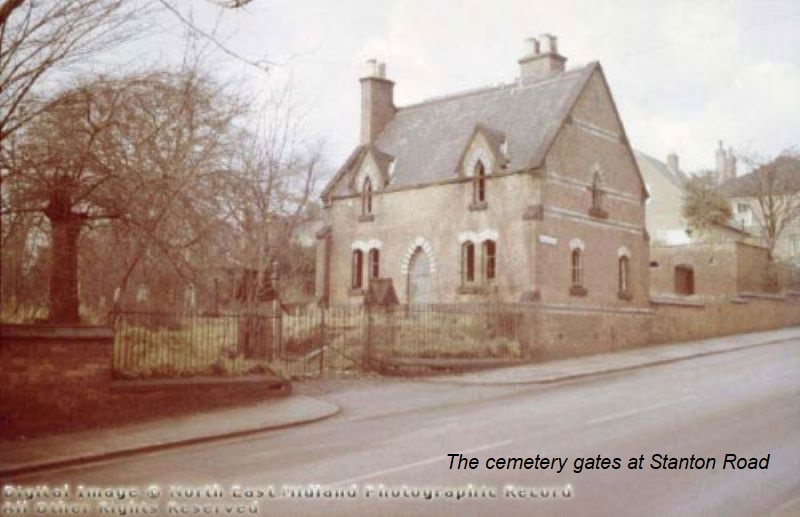

Walking away from Old Gallimore‘s residence in Stanton Road, Adeline now takes us to visit “Mrs. Derbyshire, senior. Her house on the bank was the last in the road, until the cemetery house was built”.

Baptised Sarah Simpson, Mrs. Derbyshire senior was the mother of butcher Job Derbyshire. She was the oldest surviving child of Boot Lane farmer John Simpson and Sarah (nee Nightingale) and died at her home at 17 Stanton Road in September 1880, aged 77.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Churchyards, chapel burial grounds and cemeteries

Up to the nineteenth century most people were buried in Parish Churchyards which by that time had to cope with the increasing demands upon them resulting from the rapidly expanding population. In the previous two centuries some burial grounds attached to their chapels had been established by nonconformists. For example, in Ilkeston such grounds were to be found at the Independent Chapel in Pimlico, at the Unitarian Chapel in Anchor Row, and in South Street connected to the Baptist Chapel.

Also, nationally, there were a small number of profit-making private cemeteries, while the first public cemetery was opened in 1819 at Norwich. However this was not followed by a national movement to create cemeteries and there was no legislation to facilitate their establishment. A Parliamentary Act of 1853 allowed the establishment of public cemeteries by publicly-financed Burial Boards, leading to a massive growth of such cemeteries in the following 20 years.

By 1850 urban churchyards were quickly filling up, were exclusively Anglican and were often regarded as ‘public health nuisances’. And it was that in March 1856 the Rev. Ebsworth, vicar of St. Mary’s, received a notice from the Secretary of State (Ministry of Housing and Local Government) informing him that that the latter was to recommend the partial closure of the churchyard at the parish church, under the terms of the new Burial Acts (1852/53/54/55), to ensure the protection of public health. It was felt that contaminated and offensive matter from decomposing corpses might find its way, perhaps via rainwater, into open wells and streams providing drinking sources to the local population. The natural consequence of such a closure was that the parish would then have to provide a cemetery, incurring much public expense.

The vicar immediately called a vestry meeting at which the majority of those present were in favour of challenging and appealing against this decision. There was, however, a significant minority – including Matthew Hobson and John Ball – who favoured the establishment of a committee to inquire into the feasibility of providing a new burial ground.

Because of this disagreement, a poll was organised and soon taken, the result of which showed that a majority was in favour of challenging the decision of the Secretary of State… “in the opinion of this vestry, it is not possible that interments in Ilkeston churchyard can be injurious to the public health; and that … the Secretary of State must have been guided by a report founded on misstatements of facts”.

In other words the Secretary of State should check his facts more carefully and employ better Inspectors to collect information for him !!

The Derby Mercury congratulated the Ilkeston vestry on the stand it had made against unnecessary interference in their parochial affairs.

The churchyard was not closed and thus a new cemetery for Ilkeston was delayed for several years.

Stanton Road’s cemetery

But a new cemetery did arrive in the shape of Ilkeston General Cemetery, located in Stanton Road.

In September 1863 an item in the Derby Reporter appeared, stating that in Ilkeston ”some time ago great efforts were made to obtain a cemetery, but in consequence of a division of opinion the project was abandoned, and an addition was made to the churchyard. Recently a company has started to carry out the original intention. A very eligible piece of land has been purchased from Mr. Hobson and Mr. B. Wilson, of Derby has been appointed architect”.

The land was just over two acres in area, ‘on the brow of a gently rising hill‘.

In December 1863 tenders were requested by ‘the Ilkeston Cemetery Company’ for the building of a Cemetery Chapel, Sexton’s Lodge, Entrance Gates and Boundary Walls, for forming and levelling the ground, constructing roads and planting vegetation.

The first person to be interred in the new cemetery was Ann Shaw, wife of builder Thomas of North Street, who died on New Year’s Day of 1864. She was buried in Plot No. 6 in the ‘second class’ section of the cemetery on the afternoon of Wednesday January 6th. Her husband Thomas paid £4 4s 2d in fees and this included three guineas (£3 3s) as the cost of reserving Plot No. 5 for future use.

Both Ann and Thomas were members of the Primitive Methodist Chapel.

In January 1879 the annual meeting of the shareholders of the General Cemetery reported that there had been upwards of 760 burials there. Coincidentally the first burial of that year — No 761 — was that of the grandson of Thomas Shaw who had died on January 6th.

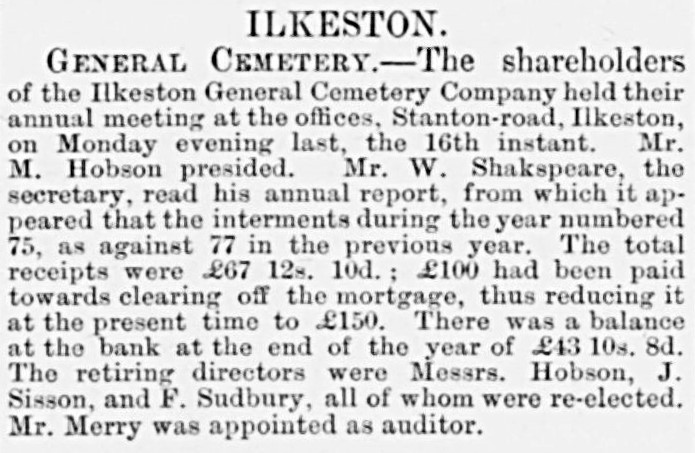

And a few years later, at a similar meeting, more progress …

from the Alfreton Journal (Jan 20th 1882)

The cemetery was in use for 83 years and closed for use in January 1947. The last recorded burial there was that of Harriet Dunkley, aged 89 years, on January 21st 1947.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

The funeral of Samuel Potter, and its aftermath

In a letter to the Advertiser, March 28th 1930, Adeline wrote that “in those days (i.e. the 1860’s) all funerals took place on foot, and I remember the long procession coming up South Street from the Park when Mr. Sam Potter senr., the cricketer, was buried. All the bearers wore black silk scarves fastened at the side under the arm, also the male mourners wore black silk hatbands fastened at the back and flowing down. All funeral processions walked in the middle of the road. I wonder what motor cars, trams, buses, and all the other quick traffic would do if a long funeral procession appeared in their midst.”

Adeline would be recalling the funeral of coal master and farmer Samuel Potter, eldest son of Samuel and Sarah (nee East), which took place in July 1860.

Old Resident could also well recall the same funeral, when the new Boy’s School in the Market Place was being built. He was one among very many on-lookers to see Samuel buried near the entrance gates to St. Mary’s churchyard.

But then … a scandel !!! The body “was exhumed a year later in order to disprove a wicked suggestion as to the cause of his death”. About nine months after the funeral, rumours began to circulate in Ilkeston that Samuel’s death was a result of poisoning by some members of his family, rumours which seem to have carried some weight as the police became involved, the divisional coroner was informed, and the body was exhumed from the family vault in St. Mary’s churchyard and taken to a room at the Sir John Warren Inn. There a post-mortem examination was conducted in the presence of several doctors and legal witnesses before the body was re-interred. The state of decomposition made examination extremely difficult though Bath Street surgeon James William Eaton could detect no smell of poison.

At a subsequent inquest several of Samuel’s servants talked of ‘powders’ being supplied by local druggists Richard Smith Potts, Thomas Merry and George Purcell some months before Samuel’s death, on the instructions of his wife Ann, and of Samuel being very sick after taking the medicine. This was later revealed to be small amounts of tartar emetic, very harsh and powerful but only poisonous in large doses.

On the morning of Samuel’s death Nottingham physician William Tindal Robertson had been called to see him, and found the patient initially unconscious before being seized by epileptic convulsions which continued intermittently over a two hour period.

When the doctor left, Samuel was on the point of death but displayed no signs that either ‘vegetable or mineral poison’ had been taken; the doctor was of the opinion that death was due to ‘a series of epileptic attacks, complicated by apoplectic effusion’. ‘No poison could have produced such symptoms alone as those I saw except prussic acid, and in that case the death would have been very rapid and the smell unmistakeable’.

Both Mr. Eaton and Charles Grant, surgeon of Heanor, concurred with this opinion as to the cause of death.

In his summing up, the coroner could find no grounds for giving credence to the report of poisoning and the jury agreed — death was due to ‘natural causes, that is Epilepsy’.

At the inquest, the evidence given by Charles Hampson, who had worked regularly for Samuel up to his death, and his 15-year old son, who had also been employed on the estate but had lost his job, revealed that they might have been the source of the rumours.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

A strange spectacle

In May 1873 several hundred Ilkestonians were at the gates of the Stanton Road cemetery and along the paths inside to witness “a strange spectacle to native eyes” — the funeral of French freethinker Antoine Barthelemy Gerbaud, aged 47, a worker in the employ of Edmund Tatham and who had died at the end of the previous month.

The funeral procession began just before noon at the former Nottingham Road residence of Antoine, its members about 80 in number, many of them travelling in from Nottingham.

“The coffin was carried on two wooden bars by four bearers (Frenchmen), and was covered by a pall. On the pall lay a red flag unfurled, and on the flag a crown of ‘immortelles’, within which was a bouquet of ‘immortelles’ and other flowers.

At the head and preceding the coffin walked Edmund Tatham, many of his relatives and nearly all his workers. Behind the coffin and bare-headed — no black silk scarves or headbands for these mourners – walked Antoine’s male French friends, followed by English members of the Nottingham Branch of the International Workers’ Association, and finally his family. – “it being a French custom that, at funerals, the females follow behind the males”. All the latter wore ‘immortelles’, the emblem of freethinkers in Paris.

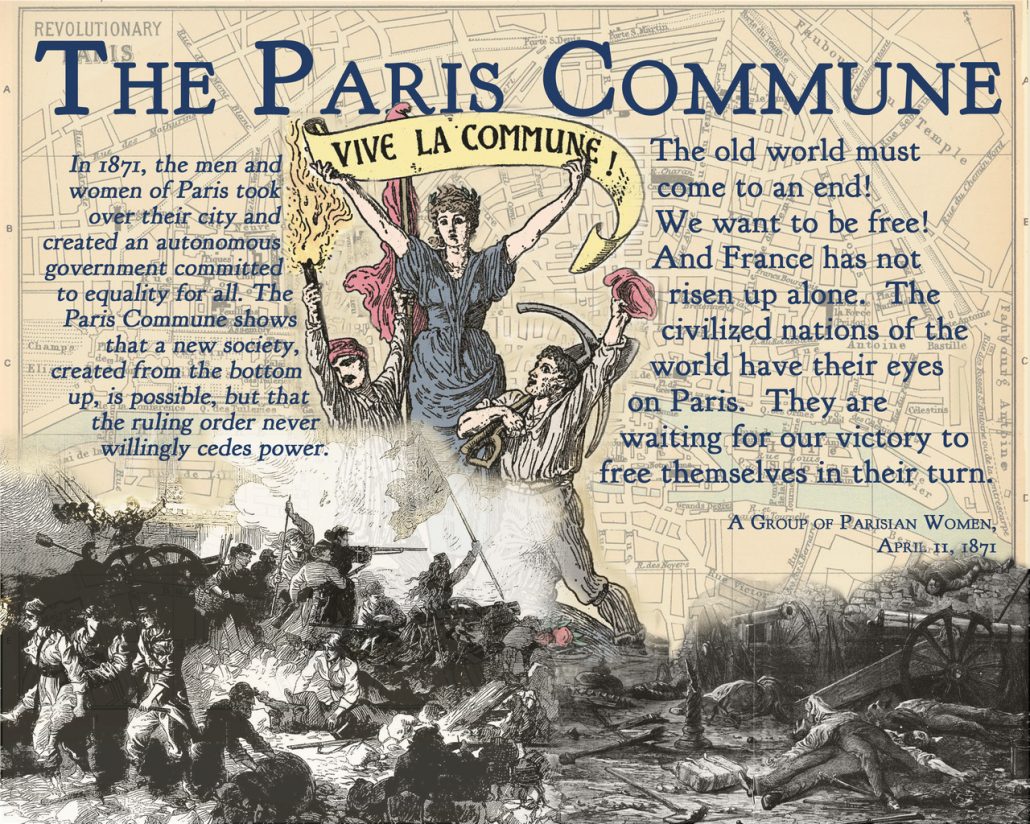

Thanks to the ‘energetic efforts’ of Matthew Hobson, chairman of the Burial Board, the cortege was allowed to pass into the cemetery and to the open grave, and there ‘Citoyen’ Hazard stepped forward to read the eulogy (in French). Antoine was a ‘socialist-democrat of the good school’, a free-thinker and a Republican, who had fought in the Siege of Paris, 1870-71, defending stoutly but unsuccessfully that city against the invading Prussian army.

He had subsequently fought ‘for the Red Flag’ as a member of the Paris Commune of 1871 “and it was very probably the result of the sufferings and privations” Antoine had undergone during these years that he developed the dropsy and liver disease which eventually killed him.

His friends knew that “this man always lived honestly, .. always defended the principles of justice and right… We know that true merit does not consist in the observance of certain superstitious practices, unworthy of an enlightened generation, but in the practice of republican virtues. We, freethinkers, accept no other guide but our conscience, and no other maxims but those of the carpenter of Bethlehem: — “Love one another, and do not do unto others what you would not like others to do unto you”. Those maxims Gerbaud practiced…. his soul, that is to say, his deeds, will live eternally in the memory of all of us, his brethren, and in the great heart of Humanity…. Brother, receive our supreme adieu!… Rest in peace, in the tomb of the just!”

A few more speeches and courtesies followed, and the ceremony was brought to a close.

“The party, after partaking of lunch at the house of Mrs. Daykin, the Needle Makers’ Arms, walked back to Nottingham. The weather was propitious throughout.” (IT May 1873)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

St. Mary’s widens its scope.

In August 1880 a meeting of the Derbyshire branches of the English Church Union, held at Belper and which comprised Belper, Ilkeston, Staveley and Derby, passed the following resolution: “That this meeting desires to record its earnest protest against the passing of the Burials Bill now before Parliament, by which it is proposed to compel the Church to allow her church-yards, which have been solemnly dedicated to Almighty God for the burial of her own children to be desecrated by the exercise of strange ministrations, and may be by persons who deny the divinity of her Lord…”.

Present at that meeting, though not a member, was the Rev. Joseph Hall, rector of Shirland, who threatened that if the bill became law, he would defend his churchyard and only yield to force.

Despite this opposition, the Burial Laws Amendment Act was passed two weeks later, thus allowing non-Anglicans to conduct a burial within the parish churchyard. Previously only Anglican priests could do this even if the deceased was, for example, a Methodist.

In Ilkeston the first such burial at St. Mary’s was that of Margaret Ellen Sowray on Saturday October 23rd 1880. She was the 16-year-old daughter of plumber, glazier and painter John (deceased) and Catherine (nee Campbell), and the service was performed by the Baptist minister Arthur Charles Perriam.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Cemetery neglect

In the Adeline’s letter of 1930 (see above) she also recalled a visit to the Cemetery —

“Some time ago I went into the Stanton Road Cemetery and I could not help contrasting its present appearance with how it looked years ago.

There were only two seats that could be sat upon. These were in view of Stanton Road; the others were rotten and falling to pieces. The grass had been neglected, and the graves in most cases did not appear to have been tended by loving hands. In the centre, or thereabouts, there was a great heap of rubbish, broken trees, etc. I wonder who is responsible for that neglect. Surely those who lie in that little cemetery have some friends left to give a little care to the last resting place of those gone before”.

We might compare these words with those of tailor, toll-keeper and poet William Campbell.

On a summer Sunday evening in 1870 William was wandering around the cemetery. After some time reading the inscriptions upon some of the main tombs he strolled further into the grounds.

“.. other little graves, less costly presented themselves, embroidered with small white pebbles, also the initials of the names of calm and peaceful sleepers laid carefully down below in their long last resting places. Another class of graves were tastefully adorned with shrubs and flowers, evidently kept alive by frequent watering, and no doubt many a time watered with tears as soft as the pearly dewdrop, the surest token of a mother’s fond affection. The remembrance of the dead by some of the lighter minds may soon be forgotten; but not so with others who mourn for their dear departed ones with a deep heartfelt sorrow, and although we do not witness in the floral department, the marble covering, the costly monument, or the humbler headstone, to tell the place where all that is left of lifeless mortality is laid, yet still, each little memento we witness, proves at once that some unseen and secret influence hath been at work unaided by the use of the sculptor’s mallet or chisel, and hath engraven deep on the living memory, deep as on the hard and beautiful marble, in living characters ‘Forget me not’’.

(letter in the IT, dated June 21st, 1870, appeared July 9th)

And in November 1892, John Cartwright paid a visit from Derby to his ‘old town’ and described it in the Pioneer of May 1893 …..

At the Stanton-road cemetery, I found plenty of matter for contemplation, for in its quiet bosom rest two of my dear sisters and the dear mother who bore us; near them lie many old neighbours and friends. Some names I saw writ in stone remind me of lives well and usefully spent, whose influence for good is still felt. Amongst the tombs I saw Mr. Charles Haslam, whom I knew 50 years ago, but who knew me not, although he politely spoke to me in passing.

John’s mother was Catherine nee Swanwick who died on September 28th 1875, aged 74, and was buried in a third class grave on October 1st, costing 10s.

John’s eldest sibling Martha married William Gregory, of West Hallam, an engineer and local Wesleyan preacher. She died om February 14, 1890 at 20 Byron Street, aged 66, and was buried on February 16th, in grave 463, 2nd class, costing £1 3s.

Sister Elizabeth, two years younger than Martha, married lace maker Joseph Beardsley on April 28th 1853 at Ilkeston Independent Chapel. She died at Primrose Hill, Cotmanhay, on May 9th 1891, aged 65, and was buried on May 12th 1891, in the 2nd class area, grave numer 22, again ccosting £1 3s.

There was a third sister, Alice, buried in Stanton Road cemetery — after John’s death. She married John Beighton, brickmaker and later colliery banksman, in 1876 at Ilkeston Independent Chapel. She died in October 1894, aged 67, and was buried on October 13th, in garve 411, 2nd class, costing 13s.

Can you still find these graves ?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Let’s wander, like William and John, among the graves and examine the details shown in some of the memorials.