1875 and the State of Education in Ilkeston

In October 1875 the Local Gossip column of the Ilkeston Pioneer asked its readers to consider the state of educational affairs existing in and around Ilkeston.

“I know very well that many of my friends entertain a wholesome dread of having a School Board thrust upon them but just let us briefly enquire what steps they have taken to avoid that unpleasant alternative”.

At this time the Anglican Church community had the upper hand in the contest for ‘education supremacy’. Three new National schools had just been built on the Cricket Ground, while being built were new ones at Cotmanhay, at Little Hallam and on the Common – places for over 1500 children — all done with the voluntary effort of just a few people.

“It is now time for the many to come forward cheerfully and spontaneously, and assist by liberal contributions in seconding the work so handsomely begun”.

And to the parents of Ilkeston’s children .. “when these noble schools are finished, do not let them go empty from day to day. … see that the children fill them, and by so doing you will hear nothing of School Boards”.

The new schools on the Common were the Trinity Schools of Granby Street whose foundation stones were laid in December 1875.

And after reporting this, the Pioneer was convinced that when they were built, the requirements of the Education Department would have been met and “there will, therefore, be no necessity for the formation of a School Board”.

It went on to reiterate its argument that schools provided by such Boards were unsatisfactory and far too expensive to establish. The new National schools on the Cricket Ground and at the Common had been provided by the voluntary sector at a cost of £3 per pupil — exclusive of the sites of course, which had been provided free of charge by the Duke of Rutland.

In comparison, new Board Schools at Bradford (the most expensive) had cost £17 7s 10¾d per head and at Bristol (the cheapest) had cost £6 13s 6¼d per head.

Also, in voluntary schools running costs were lower and pupil pass rates at the annual examinations were higher. Bible lessons were more regular and more rigorous, contained ‘elucidation and illustration’, in contrast to Board School Bible reading which offered neither ‘note nor comment’.

And once more it asked the ratepayers of Ilkeston to dig into their pockets and contribute to these voluntary schools.

Everyone should be saying “Here is a Committee, carrying out at a moderate cost a work which, under the alternative circumstances, would have been a far greater expense to me: that Committee has acclaim upon my support”.

——————————————————————————————————————-

1875 and enter Albert Eubule Evans (1839-1896)

One man had already responded …. before being asked !!

Earlier in 1875 the town’s ‘Anti-School Board Organisation’ enlisted impressive reinforcements in the shape of the Rev. Albert Eubule Evans – formerly curate of Slough and Windsor — who in February was appointed Vicar of Kirk Hallam Church.

“Of all the clerics I have met in the course of a long and varied career, I have not come in contact with one whom I regard as his equal in intellect and culture. He was a parson of the very best type, a student of ripe scholarship and wide linguistic accomplishments, and a preacher of singular power. His sermons were always short but they were models of lucidity and effectiveness, transparently earnest, and quite free from the monotonous sing-song drawl and affected delivery which one hears so often from the pulpits of the Anglican Church. He was a member of the Junior Athenaeum Club in London, the author of several books, and a profound student of German metaphysics and physical phenomena, in which latter department he was much addicted to making physical experiments. Apart from organising a debating society in connection with the Church or Mechanics’ Institute — I forget which – he took little part in the activities of the town, living his own bachelor life, and content with his books and investigations into the phenomena of spiritualism”. (RBH)

In December 1875 the Rev. Albert tried appealing to the parsimony of Ilkeston ratepayers when he calculated that Board Schools would cost at least three times more to accommodate and educate a child than a voluntary school. Thus he was sure that such facts “would be quite sufficient, in combination with the harsh procedure of school board officials, to extinguish all desire for school boards in districts where they do not already exist”.

Three month later and the Derby Mercury echoed these sentiments.

“Although Ilkeston is a town of 10,000 inhabitants, the measures taken to provide sufficient school accommodation have so far proved successful as to leave no doubt that the necessity of a School Board will be avoided”. It thanked the Church Party for raising funds and the Duke of Rutland, Lord of the Manor, for providing land for new schools at a cost of £4000, a portion of which had still to be raised but which had thankfully saved the ratepayers of Ilkeston from ‘the expensive burden of a School Board’.

But for how much longer ?

——————————————————————————————————————-

1876 and more school places are needed

In May 1876 the Government’s Education Department calculated that although Ilkeston had provided school places for 1195 children, it still needed 450 additional places and if these were not provided within six months the Department would order the formation of a School Board.

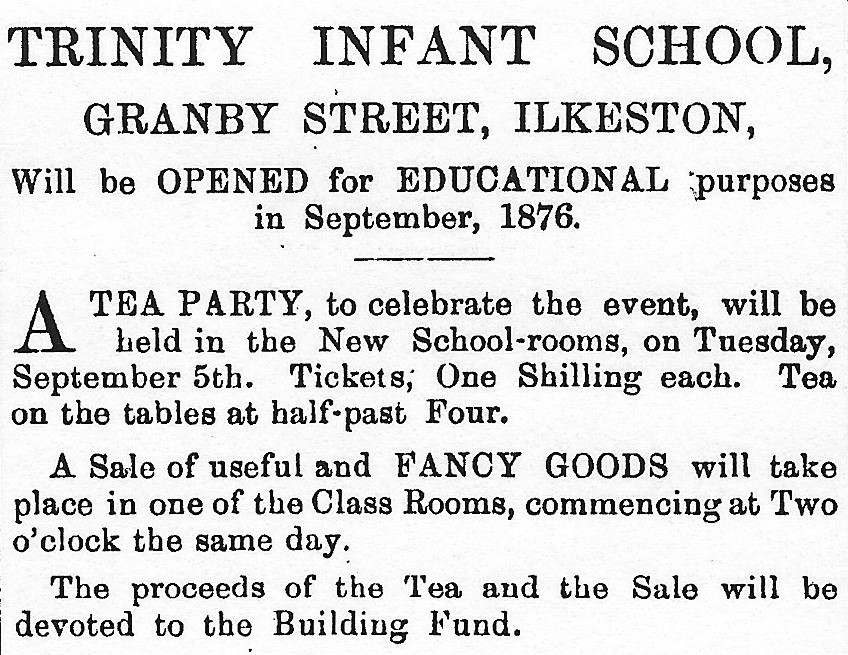

The Nottinghamshire Guardian felt confident that this deficiency in school places had partially already been met by the recent opening of the school at Hallam Fields — supplied by George Crompton, a principal shareholder in the Stanton Iron Company — and the rest of the places would be provided at the Trinity School, in course of erection. This was to be an infant school catering for several hundred children between the ages of three and seven. Thus the costly machinery of a School Board would not be necessary.

“Ilkeston will still be in a position to prove that the Voluntary system is not …necessarily inadequate and obsolete”.

But for how much longer ?

On Monday, September 18th 1876, the Trinity Infants School was opened.

It catered for children aged 3 to 7 years, its first mistress was Miss Edwards, and 200 were initially on roll.

With the completion of the Holy Trinity School on land again supplied by the Duke of Rutland, many wishful opponents of a School Board were now certain that Ilkeston would offer sufficient school places to satisfy the Education Department.

The building itself presented “by no means a handsome structure, the idea having evidently been to make it commodious rather than ornamental”.

In its first year Richard Evans of Ilkeston Potteries made several generous contributions to the school including a gift of two dozen cane-bottomed chairs.

In 1878 Miss Edwards was replaced by Miss Baker.

School Inspection Report September 30th 1878.

“The order of this large school is most satisfactory. Teachers and children are interested in their work – bright, obedient and intelligent.

“The standard preparation was very successful (except in the third class) and the rudiments are fairly taught. Grammar and Geography were unusually good. Recitations were said with taste and accuracy. Marching and exercises were satisfactory”.

Now, although there were about a dozen nonconformist chapels in Ilkeston, the British School in Bath Street was the only one school supported by them. Thus the Church of England was “educating seven or eight times as many children as their Dissenting brethren”. (figures supplied by a correspondent to the Nottinghamshire Guardian!!)

Once more the Nottinghamshire Guardian was confidently whistling in the wind.

“The inhabitants (of Ilkeston) have just cause to congratulate each other that sufficient voluntary effort has been put forth to render the advent of a School Board impossible for some time to come, and that a sound, practical, and religious education is now open for all who are desirous of becoming possessed of it”.

But how long is ‘for some time to come’ ?!

In May 1877, via large placards around town, the Local Board reminded parents and employers of the requirements of the Sandon Education Act of 1876. The board would enforce school attendance and there were sufficient school places to meet the Act’s requirements.

Thankfully — and yet again !! — there was no need for a School Board !!

But for how much longer ?

——————————————————————————————————————-

1877 and still more school places are needed

In June 1877 the School Attendance Committee, chaired by Dr. Henry George Brigham and appointed from the Local Board, wished to employ Charles Robert Baker as a new school attendance officer. He had put forward the lowest offer and was asking for a salary of £60 per annum. When the matter came before the full Board, draper William Smith — as usual! — was not happy. To him the salary demanded was too high. But equally important, Charles Robert was the husband of National school-mistress Mary Elizabeth Baker (nee Bond) and William felt that the attendance officer might use his influence to force children to attend the National schools rather than the British school.

The Chairman doctor tried to reassure the draper and his supporters; Charles Robert had been a school-master and so, being connected with school work would have a good influence; also the law did not allow him to mention any particular school; and finally the appointment was not permanent but subject to one month’s notice on either side. William lost his argument — as usual! — and Charles Robert was elected as attendance officer.

And in November 1877 he conducted a census of children within his district, counting 2382 children between the ages of five and 13.

The National schools accommodated 601 children, the British school 256, Holy Trinity school in Granby Street 300, total 1157. Other schools at Trowell, Shipley and Cotmanhay, Kirk Hallam, West Hallam and Cossall accommodated 334 more children, amounting to a grand total of 1491 places, “leaving a deficiency of accommodation of 891”. Sections of the local press (supporters of the Church Party) blamed much of this shortfall on the Nonconformists. They had a dozen chapels in the area but only one school providing 256 places. If that school were to engage certified teachers then it could expand its numbers – perhaps using the large South Street School-room which was empty except for Sunday — just as the Church schools of the area had done in the last year or two.

Despite these figures the Local Board continued for a time to reject the need for a School Board (just !!).

But for how much longer ?

The answer? Less than a year.

——————————————————————————————————————-

One man who certainly wasn’t going to concede without a stern fight was the Rev. John Francis Nash Eyre and he enlisted the sympathetic organ of the Ilkeston Pioneer to help once more in the fight.

In December 1877 he shot off a lengthy letter to the paper in which appeared …..

dire omens … a School Board will bring strife and illwill ….. it will lead to bickerings and inflictions upon honest men.

severe warnings … agitators will make the Churchmen and others pay the piper while they will take all ‘the spoils’ ….. rates will rise and be born by the few.

reminders of generosity … in recent years the Church has erected schools for 1518 children … and not forgetting that the Rev gentleman has himself made significant financial contribution.

Then the Vicar turned into an acrobatic accountant…… by a series of complicated but convenient statistics he proved that there were 1591 children needing places while the total school accommodation was 1920 !!

Ergo ?? No need for more school places …. or a School Board !!

But all in vain. The Rev. gentleman’s figures were at odds with the official ones, and the new National schools were still not sufficient to provide enough education for the growing town.

The Duke and the vicar had to admit defeat. The town’s School Attendance Committee reported that the school accommodation of the parish did not meet the requirements of the Education Act and the Local Board was thus required to set up a School Board.

——————————————————————————————————————-

1878 and the School Board cometh

The new National schools were still not sufficient to provide enough education for the growing town.

The efforts of the Duke and the vicar to avoid the establishment of a School Board were in vain. The town’s School Attendance Committee reported that the school accommodation of the parish did not meet the requirements of the Education Act and the Local Board was thus required to set up a School Board

In June 1878, just three years after the opening of the new National Schools, a School Board was to be elected, to serve for three years. In its edition of June 6th 1878 – and in very small print – the Pioneer reported that “Orders have been issued for the formation of School Board for the parish. The number of members is to be seven, and the election is to take place on the 24th of the present month”.

The newspaper then lamented (June 13th) that “such a state of things should have been brought about is nothing short of a disgrace to our town. The law says in effect ‘You people of Ilkeston are incapable of managing the education of your children; you have been allowed a long and fair opportunity of doing so of your own free will; you have disregarded the frequent warnings given you, and now my strong arm and will must step in to force you to do that which you have so shamefully neglected’”.

The Nottinghamshire Guardian reported that “Public feeling appears to run much against the Dissenters, who are accused of bringing about a School Board by neglecting to assist the Church in meeting the deficiency of accommodation”, suggesting that in the election the ‘church candidates’ would win a majority on the new Board.

Now the battle turned not towards preventing the formation of a School Board – that battle had been settled – but towards who would form a majority on the first Board — Churchmen or Dissenters?

The first election was scheduled for June 24th 1878, when both the Established Church and the Non-Conformists put forward four candidates for the seven seats, with William Mellor, butcher of Granby Street, standing as an independent.

In the ‘blue corner’, representing the Established Church, were miller William Sampson Adlington, gentleman farmer Samuel Streets Potter, draper and pawnbroker John Moss and colliery proprietor Joseph Belfield Shorthose.

In the opposing ‘yellow corner’ for the Nonconformist vote, were grocer and Primitive Methodist Stephen Keeling, draper and Wesleyan Charles Woolliscroft, lacemaker and Free Methodist Herbert Tatham, and ironmonger and druggist and Independent Churchgoer William Merry.

Prior to the vote, election meetings, some very heated, were held in various parts of the town – at Kensington, the South Street school rooms, the Primitive Methodist Chapel, open-air meetings at Cotmanhay, New England (Hallam Fields) and at the junction of Awsworth Road and Cotmanhay Road.

The Ilkeston Telegraph was convinced that “through their manly and straightforward addresses” the Nonconformists had “convinced the ratepayers of this parish that they are the men who will best educate the children and take care of the ratepayers’ pockets”.

Of course there was a plethora of voting advice.

The Pioneer found space in its columns for letters analysing the dire consequences of a Board and upon whose shoulders the blame should lie.

For example, in his letter – under the heading of ‘A School Board for Ilkeston; who are to blame?’ – ‘Churchman’ answered his own question, pointing out that “whilst the Dissenters are educating about 300 children (at its British School), the Church has made provision for 1500, there surely cannot be much difficulty in deciding who are the friends of education and which is the party most entitled to support”.

To him, it was vital that the Church gain control of the first School Board, thus administering spending on education in the town to keep down the rates. Board schools could be notoriously expensive, spending money on luxurious furnishings and “capacious playgrounds, gymnasiums, and other similar advantages so much appreciated by the juvenile element”.

The Pioneer took up his call to arms, set out in his ‘able letter’, and solicited support for the Church candidates.

“It is manifestly of the first import that the party which has hitherto shown itself most alive to the requirements of the parish should have a majority at the new Board. They are, by their intimate knowledge of what has been done, in knowing by whom it has been done and the method of doing it, morally entitled to the support of the whole parish on the day of election; and the greatest security the ratepayers can have for an efficient discharge of the new duties will be obtained if they select the men of experience in the old”.

For the Ilkeston Telegraph this was simply ‘Bible men’ boasting about what they had done for Education in the town, like a set of ‘ecclesiastical braggarts or inflated Pharisees’. They have not spent money and built schools for the good of the town but for “the buttressing of the Established Church! It being useless to lay their irrational and contradictory dogmas before intelligent and thinking men, they aim to lay hold of the undeveloped and indiscriminating minds of unsuspecting and unthinking children. Instead of boasting about this they ought to be ashamed!” It was not the duty of religious bodies to provide for a community’s education; it is the duty of all.

The same newspaper was scathing of the Churchmen’s claims to be Champions of the Bible.

“What do Church candidates know of the Bible more than others, or value the Bible .. more than others? Their lives are not shaped in any special manner according to Biblical precepts, but simply after the common pattern of other men. To say they stand up for the Bible, therefore, is a piece of empty cant”.

To the Telegraph voting decisions meant answering one simple question. “Who are the best men?”

And if you couldn’t answer that question the Telegraph could answer it for you.

The Best Men were undoubtedly “men of average age and experience, who know the value of money, and the responsibility of children: men of fair education and intelligence, combined with respectability. Mr. S Potter is a young and inexperienced man,(he was 26 years old) and can well afford to wait. Let the ratepayers .. show the wisdom of their choice by leaving that gentleman out in the cold”.

——————————————————————————————————————-

1878 and Election Day for the School Board

In the election a form of Cumulative Voting was used. Each ratepayer had seven votes to cast as he wished – more than one or all the votes could be given to one candidate (a process called ‘plumping’) or distributed between them — resulting in much ‘tactical voting’.

William Mellor gave no effort to his election and polled a miserable 77 votes. The other candidate to miss out was William Merry.

“I remember the election day was gloriously fine” wrote Old Resident who was engaged by the ‘Church party’ in the election. “(I) can well recollect Mr. Adlington in the afternoon coming to the old Market Hall, and declaring to his supporters that he was sure to be out. The order was accordingly given to vote for Adlington in place of Shorthose (both members of the ‘Church party’), as the latter was regarded as quite safe. The result was that Adlington was at the top of the poll, and Shorthose was nearly sacrificed”.

As an indication of the size of the electorate, the votes recorded were ….

Adlington 1969, Potter 1762, Keeling 1587, Moss 1491, Woolliscroft 1385, Tatham 1275, Shorthose 1185, Merry 1088.

Thus the ‘Churchmen’ held a majority on this first Board — a situation that was to be reversed three years later.

“The announcement of the (voting) numbers was received with loud cheering by the crowd (assembled in the Market Place), and the church bells rang merry peals for some time afterwards”. (NG)

Joseph Belfield Shorthose was the School Board’s first chairman and Charles Woolliscroft was the vice-chairman. Wright Lissett was the clerk, at a salary of £25 per annum.

A few months later and the Board now had its own seal, depicting a figure of learning, with a child on either side, headstocks of a colliery in the background and the words ‘Ilkeston School Board ‘ encircling the scene. (The headstocks replaced the factories of the original design).