The Parish Pump.

From Weaver Row, Adeline guides us “to South Street through the archway, past Warner’s small plantation and the ‘parish pump’.

Ilkeston at that time, had for its water supply a few wells, but the water in them was dirty, and unfit for use.

Some of the people would collect the rain water in butts, standing against their cottage doors. This was very well in a wet season, but when a dry time came their stocks were soon exhausted, and if they had no access to the wells, which was mostly on private property, they had to patronise the parish pump that stood in a recess behind Weaver Row.

This water also was bad, but the people had to have water for daily use, so were obliged to make the best of it.

If drinking water was wanted, it had to be fetched from the Park spring, which was in the field below Hilly Holies, or from the Oak Well Spring which was in the third field below Oak Well Farm House, but either entailed a walk of a mile, or even more.

According to the Ilkeston Advertiser (1886), the Parish Pump was erected in 1839 by the Duke of Rutland, and had on it this emblem –‘Pour y Parvenir’… ‘in order to accomplish’ — the motto from the arms of the Duke of Rutland. The pump’s alternative name was therefore the Rutland Pump.

It was situated in a semi-circular recess in a wall at what was later the car park of the Ritz Cinema.

Fetching and carrying

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Wanted — one Waterworks.

Adeline’s father, John Columbine, wrote a letter under the nom-de-plume of ‘Aquilegia’, stressing the need for a good water supply for the town. This letter appeared in the September issue of the Ilkeston Pioneer and Erewash Valley Gazette for 1853 which was issued monthly at that time.

PROPOSED WATERWORKS.

To the Editor of the Ilkeston ‘Pioneer’

Sir – Permit me, through the medium of your valuable paper, to call the attention of the inhabitants of Ilkeston and neighbourhood, to a subject of paramount importance in the class of domestic and social comforts. I refer to a supply of good water, for food and cleansing purposes.

It is notorious that in Ilkeston and neighbourhood we are – at least many of us – entirely dependent upon the merest casualties for the choice element to which I allude.

There is cause for this, it is true, but I am happy to say that the cause is not necessarily permanent. A little exertion, and a little expense, would sweep this cause away, and put us in possession of that for which we thirst.

If Divine Providence had embedded minerals under our soil to the exclusion of water, we might have patiently endured all the inconveniences consequent upon such a dispensation. But not so, here water flows as plentifully as in some localities which have not the advantages of local minerals which we possess.

If this is true, the question proposes itself, Why, then, is water so scarce? The most natural answer to this question is, that the coal mines in the neighbourhood have, in consequence of their great depth and extensiveness, attracted the water from its channels into their deep, dark chambers, where it would probably find a resting place, but for the means used to throw it up, and along the various channels for its reception.

Now taking this as the proper answer to the question, we have found the true cause of the great evils about which we complain. And I am sure I have no need to hesitate before I say, that this cause is not necessarily permanent.

In these days of mechanical ingenuity many evils can be turned to good account. I feel persuaded so much may be said of this. It is true we cannot go down into the pit chambers, and with a semi-godlike voice and power drive the waters back, but we might erect waterworks in the vicinity of these pits, by means of which, a plentiful supply may be obtained for all.

The geographical position of the town is quite in favour of our project. There might be a little difficulty in forcing the water up to the highest point in the town – though by the way, the agency of steam would reduce this difficulty to nil, – but when once the water is thrown up into a reservoir, its natural tendency to find its own level will cause it to rush forcibly down the pipes laid to conduct it to any or every part of the town. But here I have no need to enlarge; the circumstance is so obviously in favour of our scheme.

Then, if water is plentiful, and the elevated position of the town is favourable, why have not waterworks been erected, and put into efficient operation, long ago? It strikes me MONEY is the great object in the way. If so, allow me to say, this ought not to be a consideration at all, when we look at the utility of water in both social and domestic life.

Perhaps you think that the wealthy proprietor of the coalfields has a just right to bear the responsibility, and create means to restore to the town what his extensive mines draw from it. I think so too, and I am inclined to think further, – if the inhabitants of Ilkeston would address a petition to the noble proprietor in question, detailing the serious inconveniences experienced by us through the scarcity of water, attributing the scarcity to his works, and praying his influence to erect water-works for us, or at least to help us in the business, so that we might have a plentiful and permanent supply of the crystal fluid, – he would not hesitate to stand foremost, if not alone, to add in this way to our convenience and comfort.

If, however, this step failed, would it be right to remain as we are? Certainly not! The appearance of the town, increasing population, greater health, – to say nothing about family comforts, – all tell us it is high time we tried some means to establish water-works.

To be as we are is disgraceful. When strangers and visitors alight in our town, especially in a wet season, they are literally amazed at the dirty aspect placed before them, and not a little chagrined at having to wade through mud, even on the principal causeways. Whereas, if waterworks were established, taps might be arranged in the streets, at convenient distances, so that the inhabitants could cleanse the causeways, in every street, from end to end, once or twice a week, without difficulty. In dry seasons the town certainly looks more decent, but then, while good housewives are sighing for soft water,, housekeepers, shopkeepers, and street-passengers are quite annoyed with clouds of dust, which the wind raises and puffs here and there at pleasure. To prevent this nuisance, I suggest that the same taps might be used for laying dust as cleansing causeways.

To remain as we are is very inconvenient. A comparative stranger feels more of this than one born and brought up in the town. Some years ago I came a stranger to the town, and I think I shall never forget the inconvenience experienced, arising from a scarcity of water. The idea of having to go to the ‘Park Well’, ‘Park Pond’, and ‘Canal’, for water, from the heart of the town, is quite insufferable; when, if water-works were established, we should have it almost at our doors.

To remain as we are encourages filth and disease. Those persons who are at all disposed to be uncleanly, will be induced to indulge their propensity by the fact of water being scarce. And others, who are differently disposed, but who are not physically able to go far to fetch water, and have not the means to send anyone else, are obliged to sit in dirt, to their great inconvenience. Dirt, however, seldom remains alone. Disease, to some extent, and in some shape, will creep into the abodes of uncleanly people. If we wish to avoid these evils, let us have water-works.

Aye, says one, it is all very well to talk about water-works, – but the means ! Yes, I say the means too. It is certain we cannot have water-works without means. But I sincerely recommend that a general meeting be convened, and that a petition be drawn up and presented to the great proprietor of the coal field, and if he refuse to aid us, then let us help ourselves: and though the work may be a great one, and we may be called on to make sacrifices, in various ways, till it be completed; yet we may cheer ourselves with the thought that we are removing from our town a standing source of disgrace, inconvenience, dirt, and disease, and also that we and our families, for generations to come, will share in the benefits consequent upon our enterprise.

I am, sir, respectfully yours, — AQUILEGIA.

(Aquilegia is a plant otherwise known as Columbine).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Ilkeston Waterworks Company 1854.

Adeline writes ….. “But it was not until 1856 that the Water-works were established, and although hot and cold running water in the bedrooms, or three taps over the kitchen sink, were not included in the scheme, the people were very pleased to have a good and plentiful supply of water brought to them through taps which were placed near to their homes.”

From the Ilkeston Pioneer, August 10th 1854.

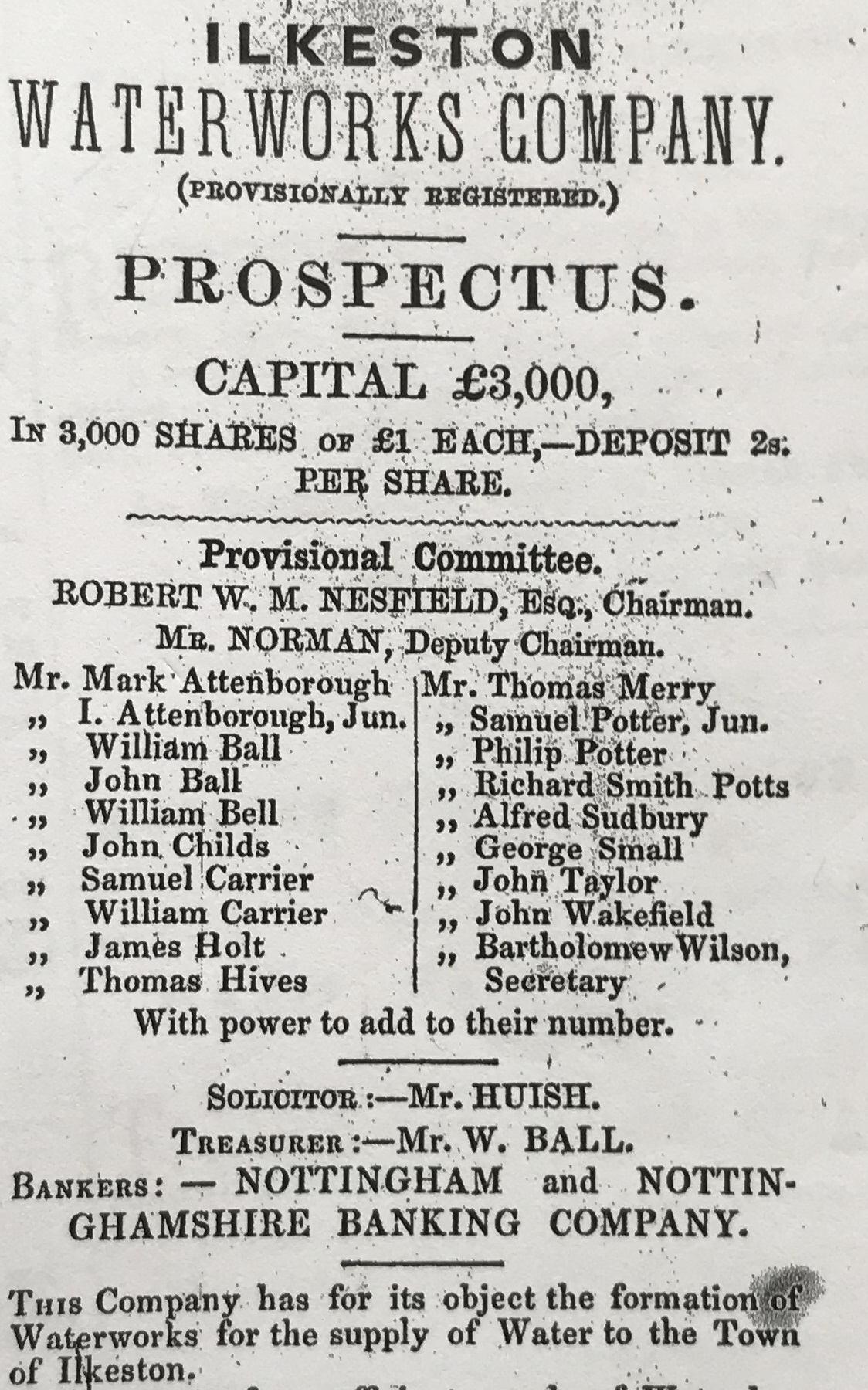

Ilkeston Waterworks Company was provisionally registered as a private company in May 1854, with its chairman Robert William Mills Nesfield, deputy chairman George Blake Norman, secretary Bartholomew Wilson and treasurer William Ball.

It issued 3000 shares at £1 each with the aim of financing the establishment of a Waterworks to supply the whole town with “an ample supply (of water) at a low cost”.

Although the price of each share was £1, it should be noted from the Prospectus (left) that potential investors were to be attracted by an initial deposit of only 2s (10p) per share, with possible further payments not exceeding 2s per month thereafter, up to the maximum of £1.

“It is confidently believed that the entire sum of One Pound per Share will not be required”

The Company was eventually set up on December 27th 1854.

In April of 1855 tenders were sought by the Company to build a reservoir, and to lay main pipes, fix hydrants, sluices and valves. By June of 1855 the Ilkeston News was reporting that building work was in an advanced state. Thus it was decided by the Directors that the reserve of 200 company shares, whch had been held back should be allotted.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Waterworks 1855

The Water Works were constructed throughout most of 1855 and by September were almost ready to supply water.

By that time the company had built a pumping shaft and a supply reservoir, capable of holding 80,000 gallons – according to the evidence given by its secretary Bartholomew Wilson at the 1875 inquiry (see below).

The pumping engine called ‘Perseverance’ was given a trial run in that month. It seemed customary to christen such machines. For example, Cresswell’s Nottingham Journal of 1776 records ‘a very large Fire-Engine’ named ‘Indefatigable’ working at ‘Ilkestone Colliery’ on the Duke of Rutland’s estate.

White’s Directory of 1857 sites the Water Works in the centre of town, with a steam engine and two filter beds.

“The engine is capable of lifting 5000 gallons of water a minute, into a large cistern, which will hold about 80,000 gallons, equal to tens days consumption”.

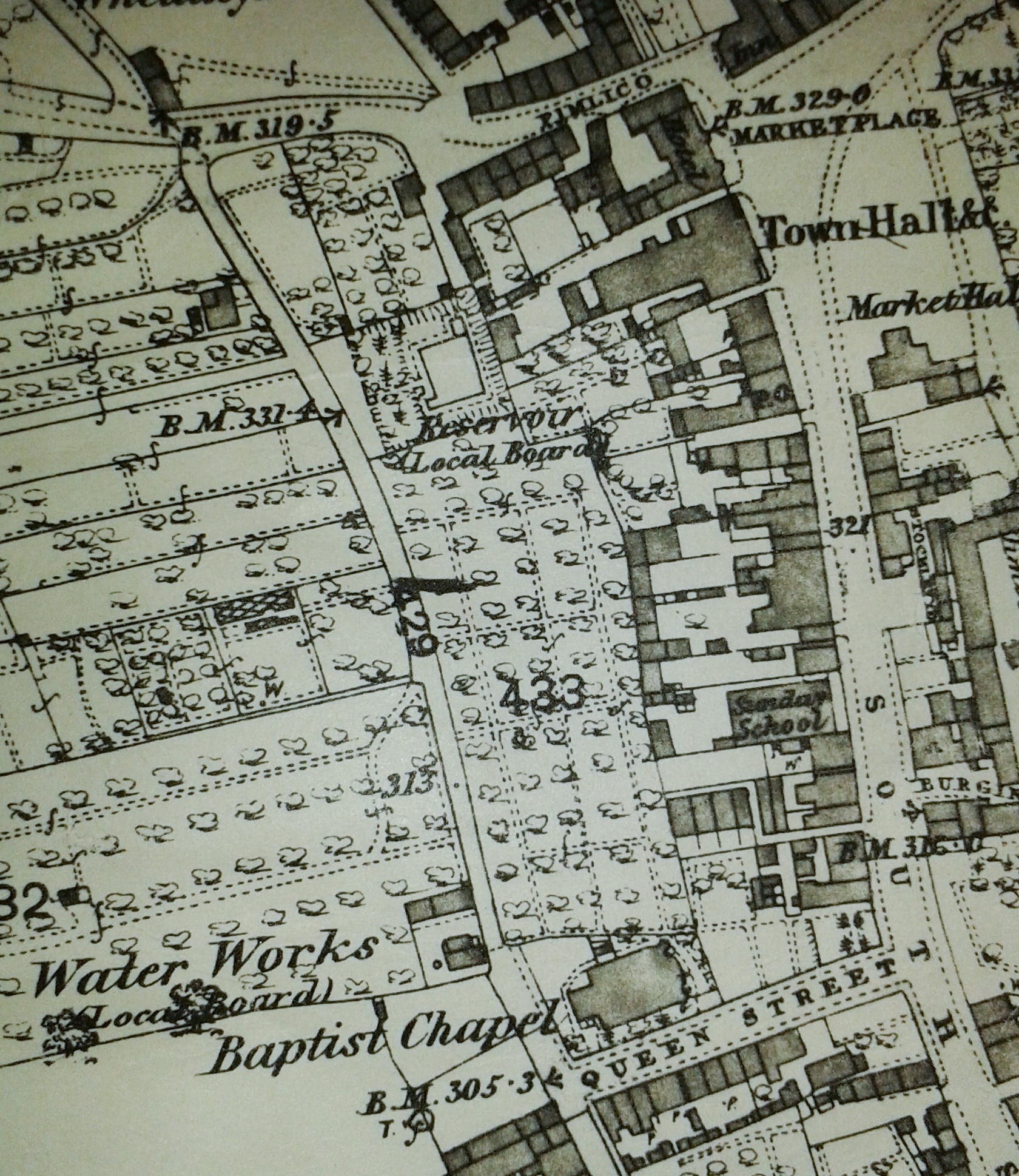

Sherwood Newman’s map of 1866 shows a pumping station on the east side of Albert Street on a site opposite the north-west corner of the Baptist Church plot — on the site now occupied by the Flamstead Centre.

A water reservoir or ‘tank’ was situated at the rear – to the west — of the Town Hall.

The Local Board takes control 1877-78

In the 1870’s many Ilkeston residents were unhappy about the quantity and quality of the water supplied to them by the water company.

For example, in 1871 an ‘Ilkeston publican’ wrote to the Pioneer complaining that on his brewing day of Friday he could not get an immediate supply of water but had to wait until the supply was turned on, after 11am that day — and it was turned off again at 4pm!!

Ilkeston’s relatively rapid growth of population in the early 1870’s and the deficiency of the water supply in some parts of the town provoked the Local Board into action. For several months in 1874/75 it negotiated with the Waterworks Company before deciding to buy all the company’s shares. To finance this purchase, and to allow it to lay more drains and improve the filtration of the town’s water, the Board applied for a loan of £10,000 from the Local Government Board. In response the Government Board set up an inquiry in July 1875 but this was quickly adjourned to allow the Local Board’s water engineer to complete his survey and present his findings.

Then in the autumn of 1876 the Local Board offered to pay 22s for each of the Water Company’s shares — an offer turned down by the Company which wanted 25s a share — an offer which was turned down by the Local Board!!

“Such capers may be infinitely amusing to the parties acting therein, but to onlookers, and especially ratepayers, the fun is of an order conducive to anything but merriment”. (IP December 1876)

In February 1877 the Local Board at last negotiated to purchase the 7354 shares of the Company at 22s each, a total price of £8089 8s.

This was “a bargain for the parish” opined the Pioneer, “(we) will save some thousands of pounds by the transaction over the scheme of erecting new and independent works”.

Do you detect a hint of sarcasm here??

In November 1877 the Local Board met to discuss the ‘Water Scheme’, by which time Mr. (John W) Fern of Chesterfield, engineer to the Board, had had time to compile his report on the town’s water supply … a feat which had taken him just over a year to complete.

At that time there were 2565 houses in the parish of which only 1167 were supplied with water by the Waterworks Company. Some of the rest used local brooks or ‘other objectionable sources’.

It was now realised that improvements were needed and consequent proposals were made.

On the Shipley side of town it was decided that a new water shaft would be sunk, a pumping station erected and a covered reservoir formed to hold 182,000 gallons.

On the other side of town the existing reservoir at Little Hallam was too shallow while the filter beds there were of little use. Thus the reservoir would be deepened, the beds converted into another reservoir while two new filter beds would be formed. A new water supply would be needed other than the one now in use from the Oak Well.

All of this would cost in excess of £11,000 and would require sanction from the Local Government Board in London.

By August of the following year the Local Board had received its required loan of £23000, and the share transfer was complete.

After sifting through 140 tenders received by the Board for the proposed new auxiliary waterworks, by September the Pioneer was able to report on ‘rapid progress’ at the new waterworks including the construction of filter beds, and service and storage reservoirs by Messrs. Beardsley and Pounder.

“The sinking of the water shafts has been commenced in connection with these works…. on the Shipley side of the town… it was decided to commence sinking near the Heanor-road, and a short distance from the Peacock Colliery…

The construction of a large reservoir at Shipley, by Messrs (William) Pounder and (Solomon) Beardsley, of Ilkeston, in connection with the same works, is now being carried forward on land previously in the occupation of Mr. Tomlinson. Supply-pipes, made by the Stanton Iron Company, are also being laid in”.

Thus, by 1878 the Water Company, now in the hands of the Local Board, was obtaining its supply from three sources …

……. the well at Shipley ….. this water was turbid and yellowish in colour, being impregnated with iron, but after filtration was bright and clear. It had the added advantage of being almost totally free from organic matters !!

……. a well in Queen Street from which water was pumped into an uncovered holding tank and which was thus subsequently contaminated by atmospheric impurities — of which there was no shortage!! At times a greenish black scum could be seen on its surface.

……. and the open reservoir at Little Hallam the water of which was being polluted by vegetable matter draining into it. (A reservoir later referred to by locals as ‘the Beauty Spot‘.

Wright Lissett was now the new Secretary of the Water Works for the Board.

Soon the town had its ‘new, improved water supply’.

But there was still unease within the columns of the Ilkeston Pioneer.

“(The Local Board has) been repeatedly advised…. that the water was not fit to drink, and that it would be a waste of public money and a danger to public health to force such a supply upon the town. …. They have spent £23,000, and they have provided the people with — what? A foul, impure, muddy fluid – offensive to the palate and poisonous to the blood – and yet they have not even now … the candour or the courage to confess they have done anything to forfeit the confidence of the ratepayers”.

To reassure Ilkeston’s water consumers, early in 1880 the Local Board sent water samples to Edgar Becket Truman, M.R.C.S., the borough and county analyst for Nottingham, and shortly after, back came his consoling words…

“The sediment contained neither lead, lime, nor magnesia. It contained a small amount of silica of carbon, but was chiefly composed of ferric oxide and alumina in the proportion of 3 to 1.

“The sewage and animal pollution was almost nil.

“The hardness, due to iron and lime (the water contained them, although the sediment did not), was half of it removable by boiling.

“The iron in the water was less than .02 or .014 grains per gallon.

“The impurities in the water would be chiefly caused by its coming in contact with clay, and, although for laundry purposes the water would not be satisfactory, the water is not injurious to health. I do not for a moment suppose that the water is in any way unfit for drinking purposes, or injurious to health.

“By a method of filtration which was very slow in operation, the water being oxygenated, the iron would be thrown down as peroxide. This would prevent the browning of linen, but the water would not be any better for drinking purposes. The cause of the varying clearness or turbidity of the water is most likely due to the greater or less speed of the water. If the water traverses its course slowly time is given for oxidation, but if it traverses rapidly there is no such time and less oxidation. In either case the water is equally sound, and I consider both samples as good as ninety-nine out of a hundred water supplies”.

So what do you make of that, Pioneer??!!

And forthwith came the answer to that question.

“No report, however favourable, can transform so objectionable a fluid as our town’s water is into one that the inhabitants can use with satisfaction in its present condition”.

By March 1881 the Local Board had borrowed almost £18,000 to purchase the waterworks and to provide finance for its extension. After all working expenses and loan interest payments were met, £137 remained from the income of the waterworks as net profit. Though the Board could – and did – argue that the Waterworks had not been bought to provide a financial profit but for sanitary reasons.

In August 1881, the Inspector of Nuisances, Charles Haslam, reported on a group of cottages, by the side of the Erewash Canal, owned by Richard Evans but rented by the Cossall Colliery Company. The houses had no supply of water except that from the canal, totally unfit for domestic purposes and a potential source of ‘fever‘. At the Local Board meeting, ‘this matter was allowed to stand over‘ !!

More water needed 1885

By the mid-1880’s the growth in the town’s population had led at times to water shortages. The town’s water supply came from several small pumping stations, at different parts of the district, most of it going into the open reservoir behind the Town Hall (seen in the map above) — this was not at a sufficient elevation to serve the whole community. The rest of the water was pumped to a covered reservoir at Shipley, at an adequate elevation.

In October 1885 water was being pumped out of the old workings of the Manner Colliery Company and then simply going to waste. It was thus suggested that the small pumping stations be no longer used, except in emergencies, but that a main water pipe be laid from the Manner Colliery works to the Shipley reservoir; the pumping engine at the colliery was sufficiently powerful to cope to lift the required volume of water to the height required. The plan would supply the district with about 276,000 gallons per day … and saving considerably on the present pumping expenses.

The water had been passed as suitable for drinking purposes. The Highway and Water Committee was to consider the plan.

We shall pause the Water Issue there — but return to it when we discuss the work of the new Town Council, from 1887 onwards.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Parish Pump and Weaver Pool; post script.

On March 24th 1855 Isaac Warner, joiner and builder, had met with representatives of the Highway Board and had drawn up the following memorandum…

“Memorandum….relative to the water course leading from the (Rutland Pump) the Hayes Ground*.

Mr. Warner agrees to make a water course down the land belonging to him and in his possession to take waste water from the said Rutland Pump and the road adjoining the said Well. Also to put two grates to prevent any nuisance from the adjoining buildings belonging to George Cheetham and Francis Sudbury to the detriment of the property of the said Isaac Warner”.

John Taylor and Isaac Attenborough signed for the Board of Highways while George Small and Ralph Shaw witnessed the agreement.

*The mention of ‘the Hayes Ground’ may refer to the presence of various members of the Hayes family who are listed at the Cricket Ground on the 1851 and 1861 Censuses. (see Burgin’s Yard and Row.) Hayes Close lay approximately along present-day Market Street (both sides).

There seems to have been a fresh-water spring in this area for at least a few centuries and contributing to what was later known as ‘Weaver Pool’. For example there is mention of Wever diche (1559), Weaver Poole (1651 and 1700). The pool was roughly at the site of the old Ritz Cinema. By 1853 — just before the Waterworks Company was established — the Pool had been drained and was an empty area of land bordering on South Street. In that year the Nottingham and Ilkeston Turnpike Trust wished to widen South Street in front of Isaac Warner‘s garden which adjoined the ex-Pool. So it proposed that Isaac might give up his land and be compensated with some of the land where the Pool had been.

The locals spoke highly of the quality of the water from the Parish Pump and were annoyed when the Local Board decided to close it, mainly because rubbish was gathering at the mouth of the well.

Fifty years after the birth of the Parish Pump — in July 1888 — the Town Council announced that Ilkeston would be graced with new iron water- fountains, at a cost of £11 15s each. One would be in White Lion Square and another at the bottom of Bath Street. After their erection there would be another fountain of better quality and style built in the Market Place.

On April 20th 1889 — the public fountain in Ilkeston Market Place was turned on by Alderman Francis Sudbury, chairman of the Health Committee of the Council.

Ilkeston’s public fountain, with the Sir John Warren Inn in the background (2022)