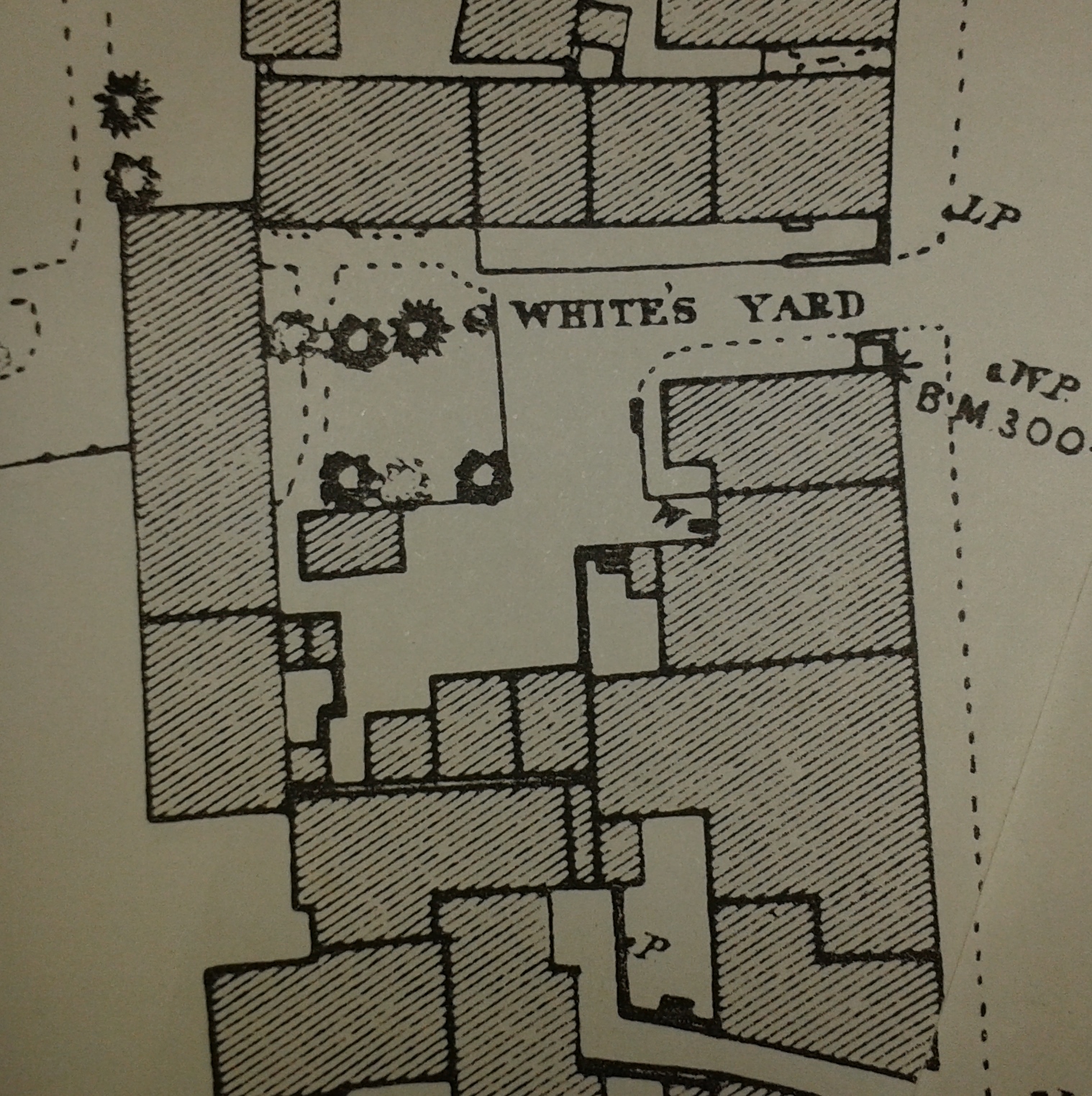

White’s Yard was on the western side of Bath Street, mid-way between the Harrow Inn and Mount Street, and past Mrs. Joseph Scattergood’s Bath Street premises.

Ruth Lowe, later White, later Revill, later Haslam.

Adeline recalls that “in Bath Street was the house with shop window occupied by Mr. and Mrs. White.”

Mr. and Mrs. White may have been Loscoe-born Woolstan Marshall White and his wife Ruth (nee Lowe) who had married on August 15th, 1842.

Woolstan was a farm labourer, the son of Cossall farmer Joseph and Eliza (nee Marshall). Ruth was the daughter of joiner and maltster Christopher Lowe and Mary (nee Allen). She was thus the younger sister of Mary, the wife of Gallows Inn labourer Joseph Moss, and of Ann, the wife of Irish lacemaker James McKenna of Bath Street.

The 1871 census shows the Whites at number 2 White’s Yard — later Bath Terrace.

Woolstan died in Bath Street on July 27th, 1875 and just over a year later his widow married Samuel Revill, veterinary surgeon – a widower for just 11 months after the death of his second wife Elizabeth.

Samuel Revill was a son of blacksmith Matthew – a former landlord of the Hearty Good Fellow Inn at Southwell, Nottinghamshire — and Mary (nee Wild) and had for a time been living in very close proximity to the Whites before moving into South Street.

A few months after his marriage to Ruth, in December 1876, Samuel moved back to his old address in Bath Street, opposite to the premises of draper Joseph Carrier.

In January 1877 the vet was called to the house of Selina Rose (nee French), the wife of collier William, to examine a pig which had recently died.

After performing a dissection of the animal he entered the house and began ‘to take liberties’ with Selina, who struggled to escape his clutches and eventually broke free.

This contretemps led to an appearance at the Petty Sessions where Samuel denied any assault but where the magistrates were inclined to believe Selina.

According to the Pioneer a maximum penalty of £5 plus costs was imposed – the Telegraph quoted a sum of £3 7s 6d.

Samuel was thus allowed to walk free from the court and return to his Bath Street home and to Ruth, his wife of six months.

In 1878 Ruth was at Nottingham Nisi Prius Court trying to reclaim money which she argued was owed to her by her first husband’s brother, Samuel White.

Before his death Woolstan had paid off a debt owed by Samuel to their father, a debt which Samuel had never repaid. However Samuel’s defence was that he had repaid the money to his brother but that Woolstan was on such bad terms with his wife Ruth, that he had never told her about this.

The judge was not convinced and verdict was returned for the plaintiff.

Samuel Revill died on October 5th, 1888, aged 57, and his gravestone in the extension to St. Mary’s churchyard reminds us that he was a Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.

And so on June 11th, 1893 and at the age of 69 Ruth moved on to husband number three who was widowed framesmith Charles Haslam of Gladstone Street.

As we have seen — when visiting the Marshall family — in the 1870’s Charles Haslam had been appointed Inspector of Nuisances to the Local Board as successor to Woolstan Marshall and had been attacked by the Pioneer for being too old for the job. Perhaps this had made the Inspector sensitive about his age.

He was born in 1814 and on the 1891 census was listed as aged 76. However by the time of his marriage in 1893 he had ‘lost’ seven years !

By the time of his death in 1901 Charles had ‘found’ them again!

Six months after her marriage Ruth died at her Bath Terrace home, aged 70,mon December 12th, 1893.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

White’s Yard.

Adeline then points out that “above Charles Chadwick’s greengrocer’s shop was White’s Yard” which housed a collection of about five families.

1] “On the right lived Mr. Stephen Rose, a miner and his family and beneath the living room window of Mr. Stephen Rose’s house was an open sewer, which received slops, etc., from the other two houses. This sewer remained open for many years”.

Born at Matlock about 1828, Stephen Rose worked at Codnor as an iron miner for a time and came to Ilkeston about 1851 where, in September of that year, he married Mary Aldred. Her parents were cordwainer Samuel and Lucy (nee Scattergood) who also lived in White’s Yard. (see below)

By 1871 the Rose family had moved into number 1 East Street to keep a grocer’s shop.

Stephen died in March 1883 in East Street and his widow kept on the shop until her death in September 1900 – at what was then 3 East Street – though she died at the home of her daughter Lucy, wife on engine fitter Stephen Rogerson, at Ilkeston Road, Marlpool, aged 76.

2] “Mr. Joseph Aldred, a machinist at Carrier’s,”

The White’s Yard Aldreds, Samuel and Lucy (nee Scattergood), also had several sons and Adeline may be recalling the youngest one, lacemaker Joseph Peter — also known as Joseph and/or Peter!

Joseph was born in 1844 and registered as Peter, was married and appears on the censuses as Joseph, and at his death on June 4th, 1923 became Joseph Peter.

On December 14th, 1862 he had married Mary Ann Reynolds, daughter of Eastwood-born lacemaker John Birkin Reynolds and Ann (nee Sisson) and then went to live close to his in-laws in North Street. He and Mary Ann died around the corner, at 4 Station Road, their home for over 30 years.

Lacemaker James Aldred was the oldest son of Samuel and Lucy. On October 2nd, 1848, he had married Club Row resident Eliza Thompson, daughter of lace hand John and Fanny (nee Chambers) and then moved into Bath Street.

Theirs wasn’t always an easy or harmonious marriage. One morning in November 1857 Eliza awoke to find that her husband James hadn’t been at home that night and was still absent. A helpful neighbour told her that if she visited a particular house, around the corner, in Burr Lane, she might find her “errant partner”. The house in question was occupied by William Robinson, his wife and several ‘guests’, one of whom was “Liz Smith”. When Eliza went to the house she discovered “Liz” lying on a bed with James, and there followed a contradictory series of events which led to several people appearing at Smalley Petty Sessions soon after.

When Eliza gave testimony in the court, she stated that on arrival she had remonstrated with her husband, but that “Liz” had intervened, had hit her, had pulled her hair, and had torn her clothing. Her account was supported by her sister-in-law Mary Rose (nee Aldred) who had seen Eliza shortly after the ‘attack’. “Liz” of course, had to take the stand to defend ‘her honour’. Her first declaration was to argue that she acknowledged no surname but was to be referred to simply as “Liz”; “she gave rather a respectable appearance. Her natural features and manner of address were somewhat prepossessing, but ill accorded with her unfortunate position; and the penetrating glance of her dark eyes, with her defiant attitude, were but timorously sustained” by Eliza and Mary. (IP). She admitted striking Eliza but that was in self-defence, and she had a black-eye to prove it !!. “Liz’s” pal Emma Knowles, another lodger at Robinson’s, supported all that “Liz” had said and her pal had never struck the ‘scorned wife’, although she may have trapped the latter’s head between her kness !!

During the course of the case Richard Vickerstaff, assistant overseer of the parish, gave evidence that ‘Robinson’s’ was a “bad house“; “the parish will indict this house; it is intolerable”.

After all the evidence had been heard, the assualt upon Eliza was considered to have been proved, and “LIz” was fined, with an option to serve a calendar month in jail.

For the rest of his life James didn’t stray far from Bath Street and died at 3 East Street in 1899.

Lacemaker John was his younger brother who lived in this area of Bath Street for the first 40 years of his life until in September 1872 he married Nottingham-born Emma Woodhouse, daughter of silk hand John and Ann (nee Jackson). Thereafter he and his wife left to live at Auckland Street in Nottingham.

Isaac and Aaron were two other brothers and we have met them, across Bath Street and involved in the sad case of George Smith.

One Saturday evening in 1860 the mother of these brothers, Lucy Aldred, was shopping at a local butcher’s shop and discovered that a crown piece had been stolen from her dress pocket. Looking around she saw two women retreating rapidly from the shop, the only other people in the vicinity.

Lucy was distraught and returned home, weeping, to tell her son Isaac who went off to apprehend the suspect pair.

He soon found one of the women about to try a similar attack on a second victim but when confronted and accused by Isaac, she denied the offence “in language more forcible than elegant”.

The woman, ‘a well-known thief named Ann Hall’, was taken into custody and it subsequently emerged that she had used the crown to purchase two penny cakes at the South Street shop of Mary Lowe.

It seems that the ‘notorious’ Ann now knew the game was up and on her way from Derby gaol to the Ilkeston Court for her trial she pondered whether she might ‘make it up’ with Lucy Aldred and what sentence she could expect.

Her turnkey suggested she should be happy with six months, which, after pleading guilty, is exactly what she got….but with hard labour!

3] “and Betty Carrier, a widow with two daughters, lived in the furthermost cottage.”

Betty Carrier (nee George), daughter of Robert and Mary (nee Skevington) was widowed in April 1844 when Anchor Carrier, her husband for over 40 years, died. He was a son of John and Esther (nee Woolin) and his brother Henry occupied premises opposite, on the other side of Bath Street.

The couple had at least eight children, one of whom was Mary Carrier.

4] Mary Carrier and Milko Jack Foster

“One daughter lived with her and she married John Foster, a cattle drover, who always wore a smock frock and top hat. He had one daughter, Esther.”

Born about 1806 Mary Carrier married John Foster in May 1835.

Mary’s illegitimate daughter, Betsy — at that time aged 3 — continued to live with her mother, step-father and grandmother at White’s Yard and was joined by several ‘Foster’ children including Esther Ann, born in February 1839.

John Foster was more familiarly known as ‘Milko Jack’, a bluff old-fashioned individual who had a kind heart beneath a rough exterior.

He was the parish pinder – elected to collect, round up and take charge of stray animals which were then shut up in the pinfold, and from which their owners could redeem them on payment of a fee. At the regular Thursday pig market John could always be found close to the pens, ready to strike a bargain over some animal or other.

In a drab smock coat, corduroy breeches and blue worsted stockings, ‘he was always present to criticise whatever was on view for sale in the form of stock. If he thought anything he would say it, – offend or please – and he was never known to whisper when he had a communication to make.

‘If he were appointed town crier by selection, his voice must have been his chief qualification. But withal, it was musical, and as sound as a bell of brass at 75 years of age. A calf is not the best of animals to get along the street, but if ever a man knew how to negotiate this stolid member of the bovine class, it was John Foster.

‘He might have been termed the ‘Lumber King’, for he would purchase any waste matter, but I believe broken cart wheels or tyres were his speciality’. (Sheddie Kyme)

The Pioneer reinforced this description when John died on Feb 26th 1890.

According to the newspaper this was one day before his ninetieth birthday and in its obituary it quoted extensively — and naturally? — from Edwin Trueman’s ‘History of Ilkeston’ published in 1880.

‘To listen to his voice, even in ordinary conversation, would lead to the belief that his lungs are in no way defective, and that his auditors must surely all alike be troubled with deafness. Calves and old lumber—- two strange commodities to go together —- will always find a ready purchaser in the person of John; and his familiar form… is not infrequently to be seen in the public street, tugging away at a rope, attached to which a youthful member of the bovine species is indulging in its friskiness and gambols. As a real, old-fashioned specimen of a bluff and outspoken Derbyshire man, John has scarcely an equal in the whole town of Ilkeston’.

Except that John was not ‘Derbyshire-born’! The majority of his census entries show John being born in Nottingham though on the 1881 census his birth-place is listed as Bristol, Gloucestershire. Only on the 1841 census is Derbyshire his recorded birth-place.

His wife Mary had died in August 1852 aged 46.

The children of John and Mary Foster ….

Daughter Esther Ann gave birth to her illegitimate son John Foster in July 1869 and when she married boot and shoe maker Alfred Henshaw in March1874 her son became John Henshaw. And they all went to live at 6 East Street.

Alfred acted as Ilkeston agent for George Tooth, ‘upper’ (as in shoe, not drug!!) manufacturer of 25 Mount Street in Nottingham. Until 1867 the latter had traded in Bath Street and we shall meet him shortly.

Esther Ann died in East Street in December 1888 and husband Alfred in June 1905.

Of the three ‘Foster’ sons, Esther Ann’s brothers, the oldest, Amos died in 1845 aged ten while the youngest, Thomas, died in 1869, aged 24.

Foster gap alert 1!

The middle son was William Foster born in October 1841. He was a lace hand employed by Henry Carrier and was the ‘tree-trafficker’ caught in the act in 1865. (See George Small, a terror to evil-doers).

I believe that in 1864 he married Margaret Taylor, whose parentage is not clear to me. She was either the daughter of John and Sarah (nee Wright) or the illegitimate child of George Foulds and Sarah Taylor (nee Wright), and a lass who had a very complicated domestic background.

Her mother had separated from her framesmith husband John Taylor in the late 1830’s to live with Mansfield-born framework knitter George Foulds in Nottingham Road. That couple had several illegitimate children and Margaret may have been one of them. John Taylor died in 1843 and his widow Sarah subsequently married George Foulds in 1849.

It was as a Foulds that Margaret married engine fitter Walter William Foster in 1864.

However before 1871 Walter William had ‘disappeared’ and Margaret was left, living in her parents’ home, with daughter Sarah Jane Foster, born in December 1866.

What happened to Walter William?

He may have died before 1879 as in that year Margaret married again, this time to lacemaker John Tilson, Derbyshire cricketer and son of Fiddler Joe. And we have seen what happened to John!! (See To Chapel Street).

Thereafter Margaret lived with her daughter who had married lacemaker Flint Pounder in November 1885.

They all moved to Sheffield where Flint worked in the steel and iron industry and where Margaret died in 1935.

Foster gap alert 2!

And what happened to Betsy Carrier alias Foster?

5] “On the left (south side) of the yard was Mr. Charles Turton’s house, used as a barber’s shop.”

As we have seen, Charles Turton lived his early life in Pimlico and was, at various times, landlord of the King’s Head in Market Place and The Nag’s Head in South Street.

The Tonsorial Turton was not Charles but James whom we have just met as we passed the Harrow Inn, at the top of this side of Bath Street (and whom Adeline correctly identifies in her 1933 article ‘The birth of a street‘).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

White’s Yard and Whitt’s Yard.

White’s Yard should not to be confused with Whitt’s (or Whit’s) Yard, which was further down Bath Street and on the other side, a few houses north of the Queen’s Head Inn.

However Arthur Charles Perriam, Baptist Minister and an enumerator for the 1881 Ilkeston census did just that !! He confused the two when he was recording this area on the east side of Bath Street.

Thus, White’s Yard appears on this census when it shouldn’t. In its place should be Whitt’s Yard.

And where is White’s Yard on the census?

It is missing because it had been renamed – about 1880 – as Bath Terrace, although the original name was still used for a short time after this.

Whitt’s Yard: a disorderly place !!

In September 1886 one of the residents of Whitt’s Yard — Samuel Richards — appeared at Ilkeston Petty Sessions charged with keeping a ‘disorderly house‘ there. And police evidence suggested that for the past four or five years Samuel had been supplementing his earnings as a brickmaker by keeping this brothel. He had a woman living with him at the time — not his wife but one whom he had ‘taken in out of pity‘.

The magistrates took no pity on Samuel however, though he was allowed to chose between a fine of £10 plus costs, or two months in jail with hard labour. He chose the latter.

The woman living with Samuel in his one-room abode was Hannah Wheatley (nee Bostock), the daughter of One-armed Tom Bostock and Eliza (nee Calladine).

Hannah had married Isaac Wheatley, a lacemaker employed at Ball’s Factory in Albion Place, in August 1870, and had then lived with him in his home village of Cossall. But soon after the marriage Isaac became unhappy with the behaviour of his bride.

Hannah was quarrelsome and often went out alone at night, to be brought home drunk. She had pawned much of her husband’s clothing and the family linen and bedding in order to finance her drinking. On several occasions Isaac had walked home from his work in the early hours of the morning to find Hannah ‘entertaining strangers‘.

The last straw for the lacemaker was when he returned one night in November 1873 to find Hannah had left, and the house was locked up, with their two-year old daughter Margaret Ellen alone inside.

Although Hannah made an attempt to return to the matrimonial home, Isaac had changed the locks … and he was having no more of it!!

Thus it was that Hannah made her way — via various ‘partners‘ and several brothels — to Samuel Richards and Whitt’s Yard.

And by the time of Samuel’s incarceration in 1886 she too had several convictions for prostitution.

At the beginning of November 1886 Isaac Wheatley successfully petitioned for a dissolution of his marriage at the High Court of Justice — no prizes for guessing upon what grounds.

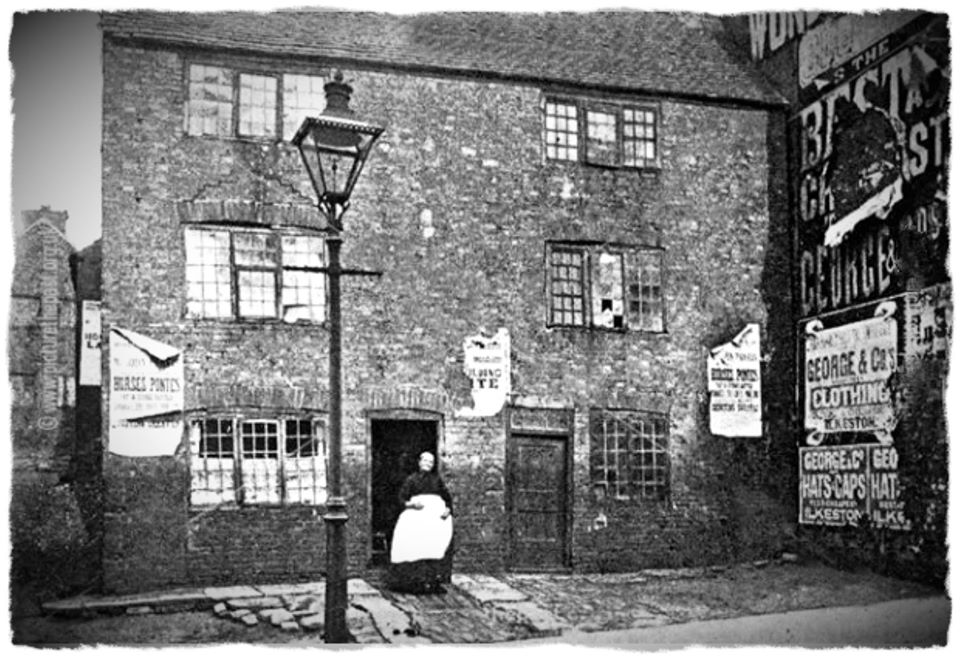

Whitt’s Yard alias Sweep’s Yard c 1890 (Trueman and Marston)

Looking at the photo above, there are two cottages, joined together, standing back from Bath Street, with the entry to the yard at the right.

By 1890 Whitt’s Yard was named Sweep’s Yard … in that year the seven freehold houses there were auctioned off by John Parkin. He was a pawnbroker, recently arrived in Ilkeston, with his family, and had premises at 157 Bath Street. In 1890 he had just established himself as an auctioneer and this was his first sale. The houses were sold to ‘Mr. Marshall of Nottingham‘ for £735.

You can find Sweep’s Yard on the 1891 Ilkeston census.

As we have seen above, Hannah Wheatley’s father, Thomas Wheatley, was known as One-armed Tom … I’m not sure how he came by this nickname; in all sources he is referred to as an engineer (at a factory), and so might have suffered a work-related, industrial accident ? He is mentioned in the Ilkeston Telegraph (March 1874); “Thomas Bostock alias One-armed Tom, engineman of Ilkeston, … Isaac Wheatley of Cossall is the husband of his daughter”. Apparently there was bad blood between Isaac and Tom, and this resulted in a court case at Ilkeston Petty Sessions on March 26th, 1874. The case is also mentioned in the Nottingham Journal for March 28th.

Karen Masters have very kindly sent some of her family history research on these Bostock, and particularly abot another of Tom’s daughters, Hannah’s older sister, Susanna

One-armed Tom’s daughter Susanna Bostock was born in 1848. I have found her in 1851 at Ilkeston Common, and in 1861 in Bath Street, with her family of Bostocks. However by the 1871 census she had moved to 1 Providence Place, St Peter’s, Nottingham, and was living with a husband, William Brooks (born about 1831 in Loughborough, and died on February 9th, 1910 in Carlton, Nottingham), and their 6 months old son Samuel, born in Nottingham. I have never been able to find a marriage record for Susanna Bostock, which leads me to believe that she never did marry. I have concluded that when she died at aged 31, she was still Susannah ‘Bostock’ (cited on the Basford registered death index record Vol. 7b, pg. 121). She seems to have been buried at All Hallows Church in Gedling, Notts., on June 1st, 1880.

The Bostock/Brooks family unit:

William Brooks and Susannah Bostock had 4 children together, only the first child, son Samuel (1870-1918) was given his father’s surname (but retaining his mother’s surname as his middle name). The daughters’ surnames were Bostocks: Louisa Adelaide Brooks Bostock b. 1875; Selina Bostock b. 1877; Susan Brooks Bostock 1879 – 1881.

NB. Interestingly when son Samuel subsequently became a father to 2 children he gave them the middle name of ‘Bostock’ too: Samuel Albert Bostock Brooks and Lydia May Bostock Brooks.

I find Susanna and William’s ‘non-marriage’ relationship quite unusual, but haven’t been able to arrive at a definitive explanation for it other than William Brooks was possibly already married when they met and divorce in those days maybe wasn’t an option (in the 1861 census in St Peter’s, Nottingham there is a William Brooks living with a wife Mary Brooks and 1 year old Clara Brooks).

A twist in the story of course is how the ‘Bostock’ name has flowed through this ancestry line, when the original ‘Bostock’ (one-armed Tom) was actually born a ‘Brown’ (‘Brown Brooks’ wouldn’t have had quite the same ring to it!).

Thanks Karen !!

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

We now walk on to Mount Street.