The population of Ilkeston in 1851 was 6122, in 1861 it was 8374, and in 1871 it was 9662.

This section begins to show how close and restricted the relationships within some sections of Ilkeston’s society were in this mid-Victorian period.

Adeline starts us off at 73 and 74 Bath Street (in 1871), the premises of James Chadwick. (With the renumbering of premises in Bath Street, about 1887, this area became numbers 170/172). We are standing “on the east side of Bath Street, against the Town Station, where the house and two small shops occupied by Mr James Chadwick were. One was a general store, the other had a few groceries in it, also there was a marine store at the rear of the house. Mr. Chadwick, his wife, three daughters, and one son, lived on the premises. They were all members of the Old Wesleyan Church”.

Born about 1803, the son of rag merchant Charles and Mary (nee Richards), James Chadwick married Ann Brentnall, the eldest daughter of builder John and Hannah (nee Hickton) in January 1830.

And as a result of this marriage James became brother-in-law to …

Elijah Brentnall whom we shall meet at the Anchor Inn in Market Street.

Elizabeth Brentnall who in 1842 married John Childs, china dealer of the Market Place.

Thomas Brentnall, later Mayor of Middlesbrough.

James Brentnall of Burr Lane.

and a few other Brentnalls, several of whom made their way to the north-east of England.

One dark night in May 1830 some dastardly villain cut the lead out of James’s dairy window, attached to his house, and reached inside to take two shirts, three shifts, four handkerchiefs and five stockings — they lay in a pancheon, ready for their washing the next day.

Pigot & Co’s Directory of 1835 lists James Chadwick as a cordwainer and he is described as such as late as 1841 although on the census of that year he appears as a grocer. A cordwainer is a shoe/boot maker, thus working with new leather — not a cobbler who mends footwear and so works with old leather.

By 1844 James was a ‘smallware dealer’ and he died as a ‘general dealer’ in 1872 — between those two years he was also styled as a grocer and an ironmonger.

Perhaps he owned the sort of emporium into which Ronnie Barker might walk and ask for “four candles”.

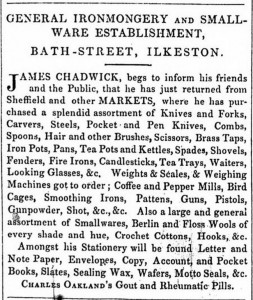

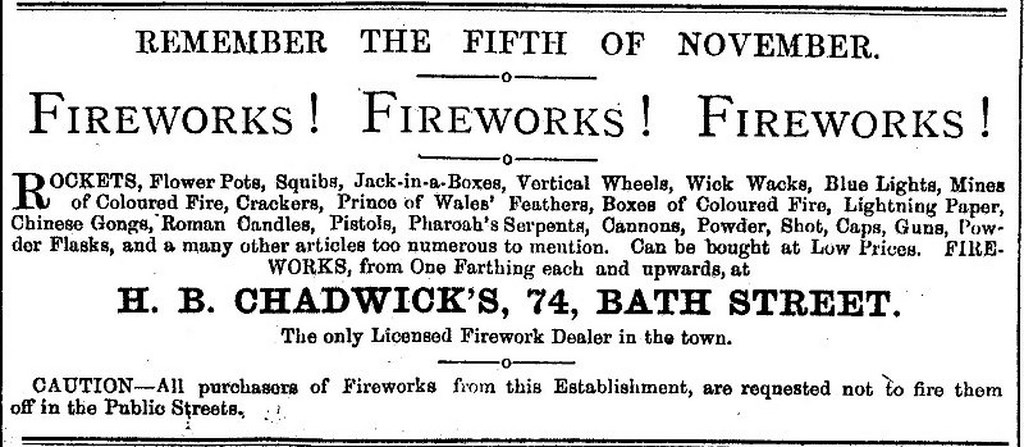

Just look at his array of goods (right) in 1854.

“There you are .. four candles” .. ” “No, fork ‘andles … ‘andles for forks !!”

A Rag and Bone Merchant ? A down-market Pawnbroker? An up-market Marine Store ? How would James Chadwick’s emporium be classified ?

Perhaps as a “Dolly Shop” ? …. The shop window was “piled high with miscellaneous items. Parts of things rather than things in themselves. Pipes and screws and planks. A small mountain of chair legs. Shoes without soles, bustles without fabric, the heads of hammers. Torn handkerchiefs. Lamps without wicks. The backs of mirrors, backs gone. Nothing whole. Nothing clean. You go to the likes of a pawnbroker to pawn your emerald ring or your solid gold watch. Knowing you can get it back when your ship comes in. Your marine stones are something else again – they’re a step below. In a marine store you pawn a chair, a nice suit, your bed, and you aren’t expecting to see none of that again. Now your dolly shop is a whole other kettle of fish. Dollys are for them who have got half of nothing and are fucked to boot. If you ever find yourself in a dolly, you know you’ve reached the very bottom of the bucket. That’s who you are and where you live. At the bottom”.

(edited extract from “The Fraud” by Zadie Smith (Penguin Books))

———————————————————————————————————————

Jokerman.

“Mr Chadwick was a humorist, and sometimes played jokes upon his customers.

“One day a man went into the general shop, and asked Mr. Chadwick for some spectacles, saying that he needed them, as he was troubled with failing sight. James gave the man several pairs to try, but he could not read in any of them.

“At last James picked out a pair, handed them to the man saying, ‘I think you will be able to read well with this pair.’ The man put them on, and said delightedly, ‘They are quite right, I can see to read well with this pair.’

“James said ‘ Yes, my friend, you do not need spectacles, your sight is quite good; the pair you have on have not got any glasses in them!’

For nearly 50 years James was a member of the Wesleyan Society and a ’much-liked’ Sunday-school teacher, “being full of anecdote and dry humour, combining amusement with instruction”.

“Someone once had the audacity to tell him that he had a ‘monkey’ on his house. Out James came with a gun, and gazing up at the roof remarked, ‘If I see anything of him, I’ll down him”. (Sheddie Kyme)

“He also among his wares, sold riddles, but he used to tell people, in his quaint style, that he had none but what had holes in; and he had no vinegar but what was sour”. (An Old Scholar 1893)

Philip Straw remembers a young girl sent to James’s store for a bucket of soft water, only to be told…..

“We have none my girl only what is very wet”. (It’s the way you tell ‘em !)

One old Ilkeston resident recalled James as a noted pedestrian, having walked to Manchester and back.

…. inspired by Dickens’ Bleak House

———————————————————————————————————————

Rocket Man.

In January 1858 James’s younger son George was serving in the ‘rag and bone shop’ when 19-year old labourer George Heaps came in to sell — not buy — a brass brick mould. This was duly purchased by the Chadwicks but then suspicious James handed it over to Serjeant Hudson.

Inquiries showed that the brass had been stolen from brickmaker John Whitehead of Spring Gardens, and George Heaps was soon taken into custody.

Found guilty of larceny at Derby Crown Court he received four months in prison with hard labour.

In 1869 the fireworks at the annual exhibition of the Ilkeston Floral Society were as usual under the able management of ‘Professor’ Chadwick and his sons who delighted everyone with “fire balloons, shells and rockets with coloured rain, coloured illuminations, and a most magnificent ‘silver tree’ some 20 feet in diameter, the effect of which was enhanced by Roman candles, jets of silver fire, etc”.

The display would have been even more spectacular had not some undiscovered rascals surreptitiously and prematurely set off several of the rockets.

Two years later and coming up to November 5th, ‘pyrotechnist’ James approached the Local Board in an effort to clarify the restrictions on fireworks.

In the previous year James had found himself in trouble with the police after he had flouted the Board’s prohibition of ‘celebrations of the Gunpowder Plot’ and he didn’t want this to happen again.

The Board decided again on a similar ban.

In the following year the prohibitions were lifted, resulting in several minor accidents around the town. Indirectly the consequences for James Wilkinson were much more serious. (See George Small; ‘a terror to evil-doers’)

In May 1871 another brass brick mould made its appearance into the life of James. This one was broken and had been stolen from the Butterley Company’s works over a year previously. At that time and searching for evidence, the police had visited James but he pleaded ignorance; he knew nothing about a stolen mould.

It isn’t clear what led them back to the grocer but they re-visited him a year later, this time armed with a search warrant. Now James’s memory had miraculously improved. Of course he could recall the mould and if they returned again he would have it ready for them.

They did return, the mould was handed over and James paid a visit to Ilkeston Petty Sessions where he was fined 40s and costs for unlawful possession. A few days later George Wheatley stood before the magistrates at Heanor Petty Sessions and was convicted of the theft of the said brass brick mould and fined 20s.

It is probable that a humorous remark wasn’t the first thing that came to James’s mind when he discovered that he had been fined twice as much as the man who stole the blessed brass brick mould!

———————————————————————————————————————

Music Man.

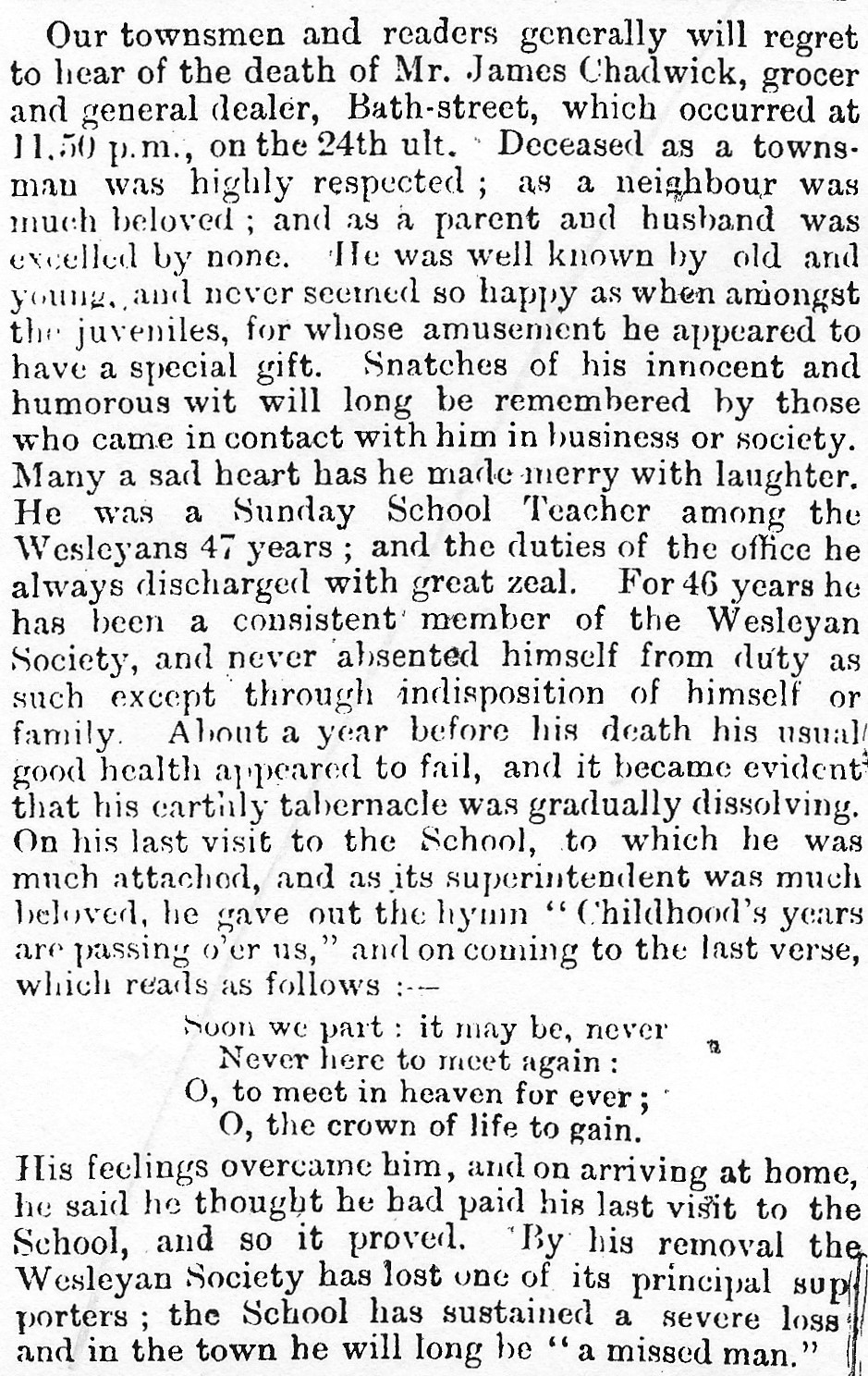

After a lengthy decline in his health James Chadwick died at ten minutes to midnight on Christmas Eve, 1872, aged 69.

The Pioneer noted that as a townsman he was highly respected, as a neighbour was much beloved, and as a parent and husband was excelled by none.

“He was well-known by old and young, and never seemed so happy as when amongst the juveniles, for whose amusement he appeared to have a special gift .. Many a sad heart has he made merry with laughter”.

“On his last visit to the School to which he was much attached, and as its superintendent was much beloved, he gave out the hymn ‘Childhood’s years are passing o’er us’, and on coming to the last verse, which reads as follows: —

Soon we part: it may be never,

Never here to meet again:

O, to meet in heaven forever;

O, the crown of life to gain.

“his feelings overcame him, and on arriving at home, he said he thought he had paid his last visit to the School, and so it proved. By his removal the Wesleyan Society has lost one of its principal supporters; the School has sustained a severe loss; and in the town he will long be ‘a missed man’”.

James’s wife Ann died on October 5th 1874, aged 67.

———————————————————————————————————————

Family Man.

James and Ann had at least nine children although three died very young — before Adeline was born.

— Frederick Thomas died in 1834, aged three.

— One daughter married Mr. Joseph Scattergood, undertaker, etc.

Born in 1834 eldest daughter Elizabeth married joiner and wheelwright Joseph Scattergood in September 1856.

We shall meet this couple as we walk down the west side of Bath Street.

— Herbert Brentnall Chadwick – HBC — born in 1836, took advantage of the family’s geographical position and, as a young man, was licensed for horse and dog cart hire, and to carry passengers to and from the station “at the shortest notice”.

Four months after the death of his father and still living with his mother, HBC found himself in conflict with horse-breaker Charles Hampson when he claimed for damages caused by the horse and cart of the latter.

There was no dispute that Charles’s horse had reared and broken two panes of glass in the Chadwick shop window, but in his defence Charles stated that a boy with a kite had run out in front of the animal, and that the kite had hit the horse on the top of the head, causing it to rear. This explanation was accepted by the Petty Sessions and Herbert left court without his damages.

Post script: In 1877 the Local Board (the ‘Town Council’) issued notices cautioning people not to spin tops, fly kites or play at marbles on the footways or carriageways, to the danger of persons riding, or driving, as well as pedestrians.

A similar caution – and including bowling hoops – was issued in 1878. The Pioneer reported that by 1879 the rules seemed to have been relaxed as it had noted the Local Board had kindly permitted the “full enjoyment of all these games in front of … the town hall, and throughout the principal thoroughfare”, adding that “several persons have already been injured, and windows broken by youngsters playing at such games”.

At this time the (Conservative) Pioneer was not a great fan of the (Liberal dominated) Local Board. The former could find any number of reasons to criticise the latter – without really trying very hard !!

HBC inherited the responsibility to provide fireworks displays at local events after the death of his father.

Thus in the year following his father’s death – 1873 — he applied for his first licence to sell fireworks, and as he complied with all the necessary regulations and as there were no objections, the licence was granted – for one year.

As Bonfire Night of 1874 approached HBC was still advertising himself as a “licensed dealer in fireworks’” and cautioning that “all persons are requested not to let any squibs or crackers off in the public streets”.

On the actual night plenty of cheap fireworks were set off, including ‘wickwacks’, a new name to the Ilkeston Telegraph if not a new invention. “Guns of various calibre were detonating at intervals until a late hour”. One of these guns was in the hands of collier Henry Henshaw who mistakenly thought such behaviour was allowed on Bonfire Night – the charge against him of firing a gun in the public street was dropped on payment of the court costs.

Similarly George Shaw and Edward Chapman thought that such behaviour was allowed on Christmas Day (1875). They had attached a piece of paper, as a target, to the trunk of a tree in Station Road, stood in the road and fired several shots at it. Unlike collier Henry they were fined.

If they had not been within 50 yards of a public carriage-way they might have got away with it.

From the Ilkeston Pioneer October 28th 1875. © Trustees of NEWSPLAN2000

One person who ignored Herbert’s caution (see his advert above) was Charlotte Grundy who let off a cracker in Derby Road, just as baker William Hampson was unloading his cart. The explosive noise startled his pony which dashed off until the vehicle crashed.

Charlotte was fined 1s and paid damages of 11s 6d for a broken harness, damaged cart and injured pony.

And by Bonfire Night of the following year HBC wasn’t ‘the only Licensed Firework Dealer in the town’.

He had competition in the shape of Sheffield-born hairdresser Henry Sleaford Clayton at the Commercial Buildings in Bath Street selling his London-made fireworks. Unfortunately for Henry the competition wasn’t to last – he died before he could see another Bonfire Night, in September of the following year.

HBC also kept up the family tradition of dealing in scrap brass!!

Several times he had to give evidence in court cases involving stolen brass items. It seemed that lost and errant brass was attracted to him like a magnet – except that brass is non-magnetic!!

For example, in July 1878 Ilkeston plumber Isaiah Sisson came into the shop with part of a brass railway wagon bearer which he claimed to have bought from his father John, also a plumber, for threepence. His dad had had it in his cellar for over six months and was glad to get rid of it.

Herbert purchased the scrap brass but very soon learned that it had not previously resided in the Sisson family cellar at all, but had been part of an engine belonging to William Sampson Adlington of the Rutland Colliery. Enginewright William Henson had identified it as a part of an engine carriage missing some weeks previously.

Isaiah appeared at the Ripley Petty Sessions and pleaded guilty to the theft, saying he would prefer to have the matter dealt with there and then, rather than before a jury at the Quarter Sessions.

The plumber was dealt a sentence of two months in jail with hard labour.

And then in December 1879 HBC was at Heanor Petty Sessions giving evidence against Edward Adams who had worked for the Butterley Company at Granby Colliery and was accused of stealing brass engine bearers.

In April 1878 HBC was fined 25s, the minimum, for keeping a dog without a licence. This was a case of forgetfulness rather than deliberate avoidance.

Five months later he hired Mary Ann Marshall, of Silkstone Common near Barnsley, as a domestic servant.

Less than a fortnight later Mary Ann left unexpectedly … accompanied by two gold rings, a table cloth, nine table knives and forks, a window blind, a pillow slip, a pair of scissors, two pairs of stockings, a towel, a shirt, other articles, and 10 shillings. And several of these items later turned up at local pawn shops.

Mary Ann was apprehended and it appeared that she was stocking up her ‘bottom drawer’ in response to the urgings of ‘her young man’ who had intentions to marry her.

After her appearance at Ilkeston Petty Sessions she was not to be with her young man for another month.

In February 1872 Herbert married Isabella Brittan, daughter of Nottingham whip maker James and Sarah (nee Roberts) and for a few years the couple continued to live at 74 Bath Street where their children, Clara Matilda (1876) and James Brittan Chadwick (1880) were born.

At the end of 1880 the family moved to Nottingham.

And HBC left without paying his district rates !!

The Local Board had to be drag him back to Ilkeston Petty Sessions and impose an order for immediate payment

In 1885 HBC was trading as a grocer and beer retailer at 30 Palin Street in Hyson Green and was still there in 1894/5.

By 1898 he had moved to 53 Woodborough Road as a fancy draper, beer retailer and shopkeeper and remained there until his death in 1902.

— Levina or Lavinia Ann died in June 1839, aged 13 months. It seems that there was no consensus on the correct spelling of ‘Lavinia’ at this time!

— A week after the death of Lavinia Ann, Lavinia (or Lavina) Jane was born.

I believe that she married journeyman joiner and widower Thomas Fox in 1879 and lived the rest of her life in Belper Street where she died at Number 8 in 1902.

— On the 1871 census, George Edmund is living unmarried at the family home of 73 Bath Street as an auctioneer. And in 1877 he lies buried in South Africa.

The grave of his parents in the Stanton Road cemetery gives a clue as to what happened to him between those years. The grave stone is marked with the words —

“George Chadwick, youngest son of James and Ann, drowned in the Fish River, Grahams Town, South Africa, while on Government duty, December 17 1877. Aged 36”.

What the stone doesn’t reveal is that George was attempting to cross the FishRiver on horseback when the animal stumbled, pitched George into the river and he was swept away. Though his body was swiftly recovered by his friends who had crossed further up-river, attempts at resuscitation were in vain. A bruise on his left eye and swelling on the left wrist suggested that he may have been stunned on a stone as he fell and was unable to get out of the river; although the water was only four feet deep at this part.

He was buried at Grahamstown, Cape of Good Hope, two days later.

George may have been serving as a policeman during the rebellion in South Africa and was due to return home shortly. He had been married a few months earlier — there is a marriage of book-keeper George Chadwick to spinster Henrietta Marian Spencer at Grahamstown on April 28th 1877.

— Susanna and Matilda were twins, born in February 1844.

Matilda, the younger twin, died two months later of pneumonia. Susannah survived and married clerk Thomas Robinson Rose in 1865. We shall meet them as we start the walk down the west side of Bath Street.

— Youngest child Matilda Ann — born in February 1846 — married general dealer Isaac Cordon in 1871 and then for a few years lived in Bath Street — where Isaac also had a reading room — at number 38 — which he opened in the winter of 1876. Thus patrons could now get hot joints and chops every day, steaks and soups, tea and coffee, read a daily paper or periodical, play a game of chess or cards, and enjoy a well-aired bed for the night — and order any picture to be framed at only 15 minutes notice !!

In the later 1870‘s the family moved to Nottingham, Isaac trading as a tripe dresser. After the death of Matilda Ann in 1894, widower Isaac married his dead wife’s niece, Florence Gertrude Washington (nee Rose), herself a widow and daughter of Thomas Robinson Rose and Susanna (nee Chadwick). Thus Isaac’s erstwhile sister-in-law became his mother-in-law.

———————————————————————————————————————

Adeline wites in one letter that “the son (of James Chadwick) married Miss Sally Hancock of ‘The Bridge House’, Kirk Hallam

Mystery alert.

By a process of elimination that son should be Herbert Brentnall Chadwick.

However Herbert married Isabella Brittan in 1872, and they remained married and living in Nottingham until the death of Herbert Brentnall in 1902.

Sally Hancock was born in Kirk Hallam about 1846, the daughter of farm worker William and Julia (nee Daykin). Later William traded as a timber dealer, was gamekeeper to Colonel Newdigate and for a time lived at Bridge House in Kirk Hallam.

Bridge House from the main Ladywood Road (above) and from the rear just before demolition in 1961. It was built in the 1790’s for the Nutbrook Canal Company and served as a tollhouse. On the 1851 Census Sarah Hancock and her family are living there.

On the map below, Bridge House is marked at number 88 (lower middle) on the Main Road through Kirk Hallam, coming from Ilkeston (right)

I believe that Sally married farmer Charles Just in 1877, soon moved to Risley Park, and eventually, at the end of the century, moved to Boya Grange, Dale Abbey, where she died on February 25th 1910.

———————————————————————————————————————

Of the siblings of James Chadwick …

— the eldest was Ellen, born about 1794 and who, in 1816, married Ilkeston collier William Ellis. The majority of their children were born in Ilkeston, before, about 1828, the family moved to Cossall, Nottinghamshire, where they continued to live.

— we shall meet a younger brother Charles towards the end of our journey, on the west side of Bath Street.

— we are unlikely to meet another younger brother, John, as he had been transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). In July 1843 he had been convicted at Derby Assizes of stealing a mare, ‘the property of John Bentley’, at Ilkeston on October 1st, 1839 and was sentenced to be transported for ten years. After a few months in Millbank jail, London, he departed in November 1843 on board the Marion convict ship, with 300 other prisoners. At that time John was described as 34 years old, height 5 feet 5 inches, sallow complexion, oval head and broad face, blue eyes, dark brown hair and whiskers. He had scars on his arms and two of his fingers were crippled. He was a Protestant, a boatman by trade, and could read and write.

Records also show that before his conviction, he was married on December 10th, 1836 at St. Mary’s Church to Ann Noon, the daughter of framework knitter Thomas and Ruth (nee Knighton), but had deserted his wife over four years previous to his transportation.

The same records also list one child born to John and Ann. In fact the couple had two daughters; Elizabeth, born in 1837 but who died in 1840, and Eliza born in 1839.

John arrived in Australia in April 1844.

— Coincidentally, another brother, cordwainer Samuel Chadwick, the oldest male sibling, had also married an Ann Noon in April 1821 but she was the daughter of framesmith Samuel and Ann (nee Beardsley).

Samuel Chadwick died in October 1833, aged 36, and his widow married Shipley-born coal wharf labourer and widower Henry Higgitt in March 1849. He was the father of Elijah Higgitt whom we shall meet in East Street.

— James’s sister Mary was the first wife of Ilkeston builder Isaac Warner of Burgin’s Yard, off South Street. She died in July 1832, aged 32.

Another sister, Sarah, died in June 1825, aged 18.

The youngest child was Edwin, born in 1811, who married Mary Derbyshire in 1836 and in the late 1830’s moved to Wednesbury, Staffordshire.

———————————————————————————————————————

A new way to pay old debts

As neighbours to the Chadwick property in 1871, we find the boot and shoe-making brothers, Charles Frederick and Alfred Pollard, — both recently married and starting what were to become rather large families. They were then living at number 73 Bath Street.

The older brother, Charles Frederick, had a daughter Martha, born on March 18th 1870, who, for some unexplained reason, was brought up by her uncle Alfred ‘as his own child’ from the age of three.

In 1872 the Pollard brothers acquired grocer Alfred Whitehead of Awsworth Road as a brother-in-law when the latter married Mary Elizabeth Pollard. Grocer Alfred obviously conducted a lot of his shop business ‘on tick‘, and amassed a debt book of over £100, one of his debtors being brother-in-law Alfred, who ended up owing £32.

Unfortunately for the shoemaker, the grocer then sold on his debts, for £5, to an accountant, Richard Woolstan, who immediately set about trying to reclaim the debts. And this is when the matter ended up at Ilkeston County Court in June 1890.

Perhaps somewhat wisely, Richard had reduced shoemaker Alfred’s debt from £32 to a much more acceptable £2 — but Alfred was still reluctant to pay up. And he had a unique defence; he claimed that for nearly three years until October 1886, his niece, Martha, had worked without wages for Alfred Whitehead, in order to pay off the debt, and Martha confirmed this !! As did his brother-in-law. Perhaps assuming that he was being amusing, the judge in the case declared that he would like to pay off his debts in this way as he had several nieces !!

However there was no written deed that shoemaker Alfred’s debt had been liquidated and the judge ruled that he would have to pay the amount of £2 claimed.

July 1893 was (one presumes) a very sad time for Alfred, by which time he was living in Lower Granby Street where he also had a shop. The shoemaker’s mother Martha (nee Sisson), aged 70, died at her Sheffield home, her body being brought home to Ilkeston to be buried at Stanton Road Cemetery on July 12th. The day before the ceremony, his 40-year-old wife Sarah Ann (nee Beardsley) was coming down stairs at about two o’clock in the morning when she fatally tripped, fell and fractured her skull. It was reported that she was ‘addicted to sleep walking’.

Thus the day after his mother’s burial, Alfred’s wife was buried in the same cemetery, in an adjoining plot.

And now, a third ‘death’ in Alfred’s life !!!

By this time Alfred had bought himself a very fine watch, under a five-year warranty, from watchmaker George Aram of Manchester, and it cost him £5 6s which Alfred was paying off in instalments. That was in 1890. By 1894 Alfred claimed that the watch had stopped working and so Alfred had stopped paying !!! His complaints about the watch had gone unheeded by the maker and so he had decided not to pay off the balance left owing. George took him to court and won his case, although the judge stated that he should mend the watch — if he did not, then Alfred could, and should, claim against him !!!

———————————————————————————————————————

Now on to Brussels Terrace and butcher Twells’ shop and field