Leading us on, Adeline describes …“the next shop was just above the White Lion, and Thomas Wheatley’s coal yard. It was a small general shop kept by a Mr. Gallimore.”

Born in March 1824 at Wirksworth, James Gallimore or Gallemore was the shopkeeper of Nottingham Road, son of blacksmith William and Elizabeth (nee Salt).

In 1841 he was a male servant with Ann Dodsley in Stapleford, aged 15.

In 1850 he married Stapleford-born Betsey Briggs, daughter of Amos and Mary and by the 1851 census he was trading as a tailor at Gallows Inn, with his wife and one-week old daughter Mary. Also at Gallows Inn were his blacksmith father and step-mother Jane, his half-brother Thomas, and his step-brother John Seal.

Betsey Gallimore died in 1857, shortly after giving birth to their son, Amos Briggs Gallimore, who died three months after his mother.

In March 1859 James Gallimore married his second wife Hannah Wathey, the eldest daughter of Thomas of Makeney near Derby.

By the 1861 census James had moved up Nottingham Road to the White Lion area where he was trading as a grocer, living with his wife and two daughters by his first marriage. His second marriage seems to have rejuvenated James as he had ‘lost’ several years in age – he was now a sprightly 29!!

At the end of 1864 James was declared bankrupt.

In 1871 – and now aged 42 — he was housed at 114 Nottingham Road, still close by the Travellers’ Rest Inn – at the same premises?

He also sold milk and had a milk round, recalls Adeline.

In September 1876 Captain Sandys, the local Inspector of Weights and Measures, suspected that James was selling adulterated milk.

A subsequent analysis showed it to contain 30% water which, while not harmful to adults, might be injurious to the health of infants, causing possible death or other wasting diseases.

James admitted that he had added the water thinking that his milk would keep better in the warm weather.

The grocer was dragged to the Petty Sessions where in mitigation it was pointed out that James was very deaf and had injured his powers of speech by efforts to regain his hearing. Sergeant Colton vouched that he had known James for eleven years. The magistrates remarked that if he had sold milk so adulterated for the past eleven years he must be a rich man!! He was poorer by over £2 when he left the court.

But James’s punishment was not over.

The next week he got it in the neck from ‘Tatler’ of the Ilkeston Pioneer who named and shamed him, describing him as ‘one whose initials are James Gallimore’.

“Even the ingenious plea that a little water was added to prevent the rich fluid turning sour did not avail, and poor James, after struggling with his milk-and-water cans for eleven weary years, finds out that his recipe for the preservation of milk has been based upon ignorance of a harsh law which fails to recognise the philanthropy of his endeavours to dispense a pint of pure cow juice out of something like a quart measure”.

James’s daughter Ann married John May in November 1874 but he died (in 1879?) and in 1881 she married Walter Ringham, an assistant working with her father.

At that time James – aged 50 — and family were still at the same Nottingham Road premises.

On Christmas Eve of 1885, now a baker trading in Nottingham Road with the Gallimores, Walter Ringham went out, in unusually heavy fog, with a horse and trap to deliver bread and part of his journey took him down Derby Road towards West Hallam.

It was on that road some hours later that his lifeless body was discovered lying under his horse and one of the cart shafts. It appeared that Walter had been leading the animal when it stumbled against a heap of dirt at the roadside, overbalanced and fell across the baker with fatal results. He was 23 years old.

In 1889 Annie found herself marrying her third husband, coalminer Edward Crow, at the Roman Catholic Chapel, just round the corner from the family shop. The 1891 Census shows the couple at Carr Street, with children from each of Annie’s three marriages.

Master grocer James Gallimore died in December 1888 at his Nottingham Road home and at a recorded age of 59.

His second wife, Hannah, had died in the previous month, at the same address, aged 76.

Weather Alert !! Thursday December 24th 1885.

On the same night as Walter Ringham lost his life — and in the same fog — forty-year-old James Pearson of Grass Lane, was walking along the platform at the Town Station when he missed the edge and fell onto the metal rails, fracturing his thigh.

After treatment by Dr. Carrol, James was transported to the Cottage Hospital.

Meanwhile in Stanton Road, a cart being driven down the road, missed a curve. The cart, horse and driver all ended up in a deep dyke at the side of the road. All — except the cart with broken shafts — escaped without injury.

So dense a fog had not been known in Ilkeston for a long time.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Thomas Goddard

Before James Gallimore moved in, the grocer’s shop in this location belonged to Thomas Goddard.

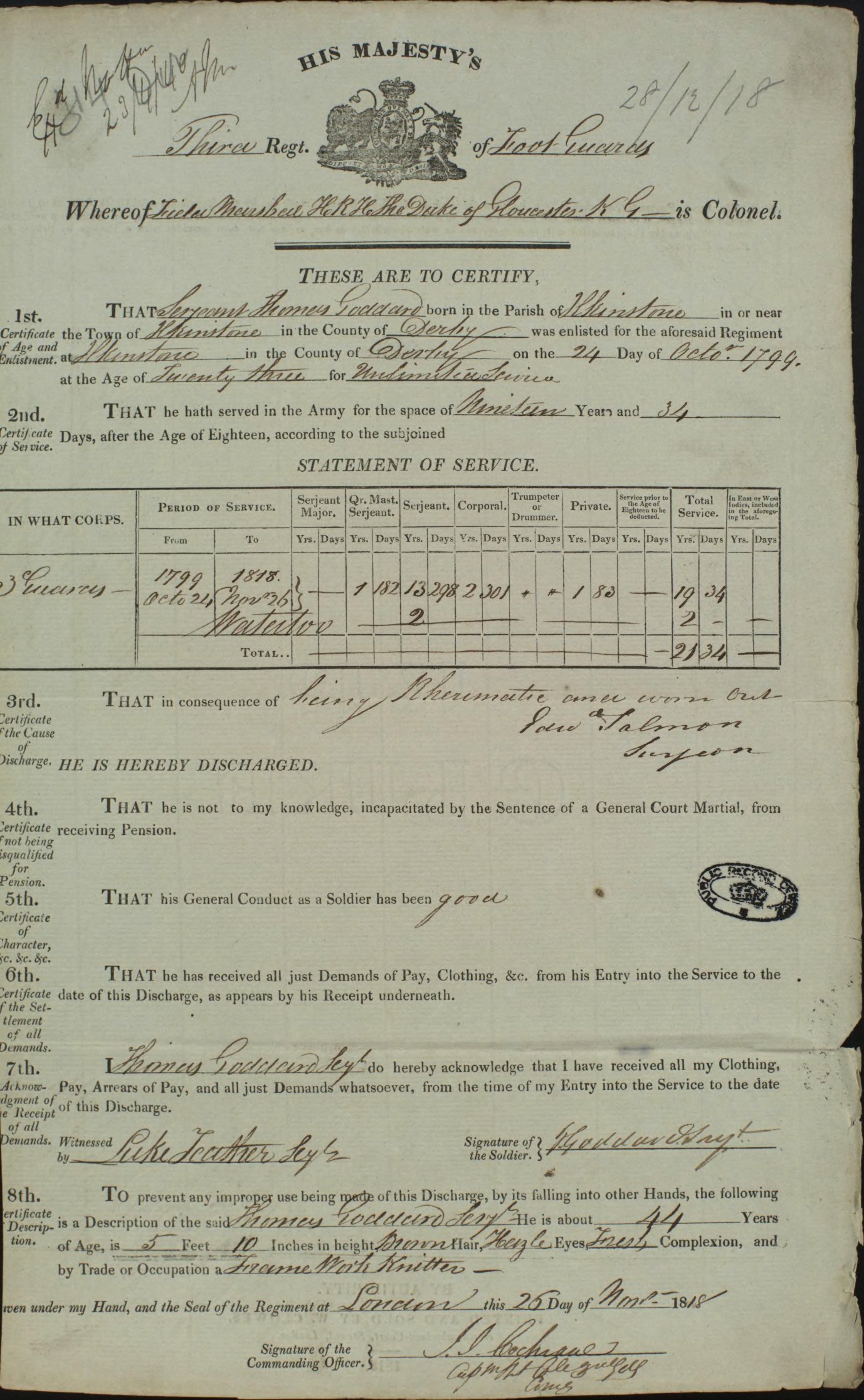

Born in 1779 he was a son of stocking weaver Jonathan and Mary (nee Burgin-Richardson). While a framework knitter by trade, he joined the army in October 1799 (giving his age as 23), for an ‘unlimited period of service’.

After just over 19 years of service, Thomas, then a serjeant, was forced out by rheumatism and being ‘worn out’. Enlisting in the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards (Scots Guards), he had served at Waterloo (1815) and so was entitled to an extra two years service to be added to his army pension.

Thereafter he returned to Ilkeston where he traded as a shopkeeper/grocer, with his wife Frances (nee Foster) whom he had married in 1806.

Thomas was the younger brother of Jonathan Goddard of High Street. He died, January 11th 1847, aged 67.

Right …. Chelsea Pensioners British Army Service Records 1760-1913 (courtesy of the National Archives/ Findmypast)

Writing in the Pioneer (December 1891), John Cartwright recalled ‘Mr. Goddard who had served his King and his country for some years, and well do I call his form to mind. I went to school with his son Fred, who afterwards spent some years with Carrier & Sons, first in Bath-street, then in their Nottingham warehouse, after which he ‘paddled his own canoe’, and is now along with his sons, leading an active life in the great city of lace and cotton.

‘Fred Goddard and my brother Tom (both born in 1830) were great chums in early life, and when Goddards had removed into East-street, I remember sleeping there with Fred, and it was arranged that we should arise early and wend our way to the river Erewash on a fishing excursion. Over-night, as arranged, a piece of string was attached to my big toe, the other hanging into the street for my brother to pull, should he arrive before we awoke. How well I remember not only the pulling of that string, but the lovely morning, when nature was looking her brightest, and freshest, and best, and our health and spirits corresponded therewith. As for the finey tribe, they numbered none the less in their native element after all our fishing….

‘Mr. Thomas Goddard, the elder son of the ex-soldier (born in 1820) in still residing in Saddler-gate, Derby, and is as straight as a grenadier, and as hale and hearty, and younger looking than any elderly inhabitant of this town’.

Thomas Goddard junior was the oldest son of Thomas and Frances, and had married Mary Smith in 1842, while working as a plumber in Derby. Mary’s father, George, was a brush manufacturer, an occupation which Thomas junior now adopted and thrived within. The couple lived all their married life in Saddler Gate, Derby, and that is where Thomas died on June 8th, 1903, aged 83, and was buried at Uttoxeter Road Old Cemetery on June 13th.

At his death, the local press described Thomas as ‘a great lover of all athletic pursuits‘. He had been an expert angler and a skilled lawn bowler; on his 80th birthday he had received a portrait of himself from the Arboretum Bowling Green Club of which he had been an active member. He had also been a long-serving member of the Derbyshire County Cricket Club Committee.

two views of this part of the south side of White Lion Square; Evans Row is on the left of the Inn.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

“The third (next) shop was nearer Stanton Road; it had not any trade to it, and was seldom let.”

This was probably sited beyond the Travellers’ Rest.