Having left behind one Inn, we now approach another, as we are walking from the Old Wine Vaults in East Street to the Gladstone Inn in Burr Lane.

And just to remind you — Adeline is describing a time when Burr Lane began at approximately what is now the car park at the rear of the Albion Centre….so the eastern (lower) half of today’s East Street was then part of Burr Lane. This name Burr Lane is a relative old one in the town’s history, claiming a written mention as far back as 1559, the first year of the Manor Court Rolls transcription by Edgar Waterhouse.

‘Burr’ may be a corruption of the Saxon word ‘Burh‘ or ‘Burg’ which was an Old English fortified settlement, probably atop a hill. If there was such a place in Ilkeston, think of where it would be sited, and then think of the roadway leading up to it — along the route of ‘Burr Lane‘ ?

The story of the Gladstone Inn reveals a little of how the beerhouses of Ilkeston have an intermingled history.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Gladstone Inn

James Warner’s beerhouse

The site of the Inn would be at the far end of this row of buildings which would also be where East Street met Burr Lane in the mid nineteenth century. The black-timbered derelict sauna parlour which you see at the end of this row was the Gladstone Inn in a previous life. However it was not the site of James Warner’s Gladstone Inn, as we shall shortly discover.

Adeline describes the area : “On the north side of East Street, and standing a little back from Burr Lane was the old public house kept by Mr. Warner. He was also the maker of a salve that was very beneficial in cases of burns, or scalds.

“Then two or three cottages in the yard”.

Just east of the Goddard houses and at the beginning of what was then Burr Lane, the premises of beerhouse keeper James Warner stood in a yard which it shared, in the 1860’s, with a brew house, piggery, stables, kitchen building and slaughterhouse, as well as the cottages mentioned by Adeline.

This was the Gladstone, or Gladstone Arms or Inn, and had been licensed for the sale of beer since the early 1830’s.

Born about 1806, James Warner was the son of joiner Thomas and Ann (nee Trueman); he was thus the brother of Isaac Warner and uncle to Thomas Warner – builders who significantly affected the topography of Ilkeston. If you examine the Ilkeston censuses of 1841 and 1851 you will find an unmarried James Warner living with his parents and then (after his father died on January 8th, 1842) with his widowed mother. They are in South Street at the site of what was to be the Town Hall. Also in the household is young Isaiah Aldred, born about 1832. He may be the illegitimate son of James. When Isaiah married on August 10th, 1856 at Heanor Parish Church he gave his father’s name as ‘James Warner‘ … Isaiah’s bride was Ann Aldred, the daughter of Heanor currier Samuel and Elizabeth (nee Bridgart).

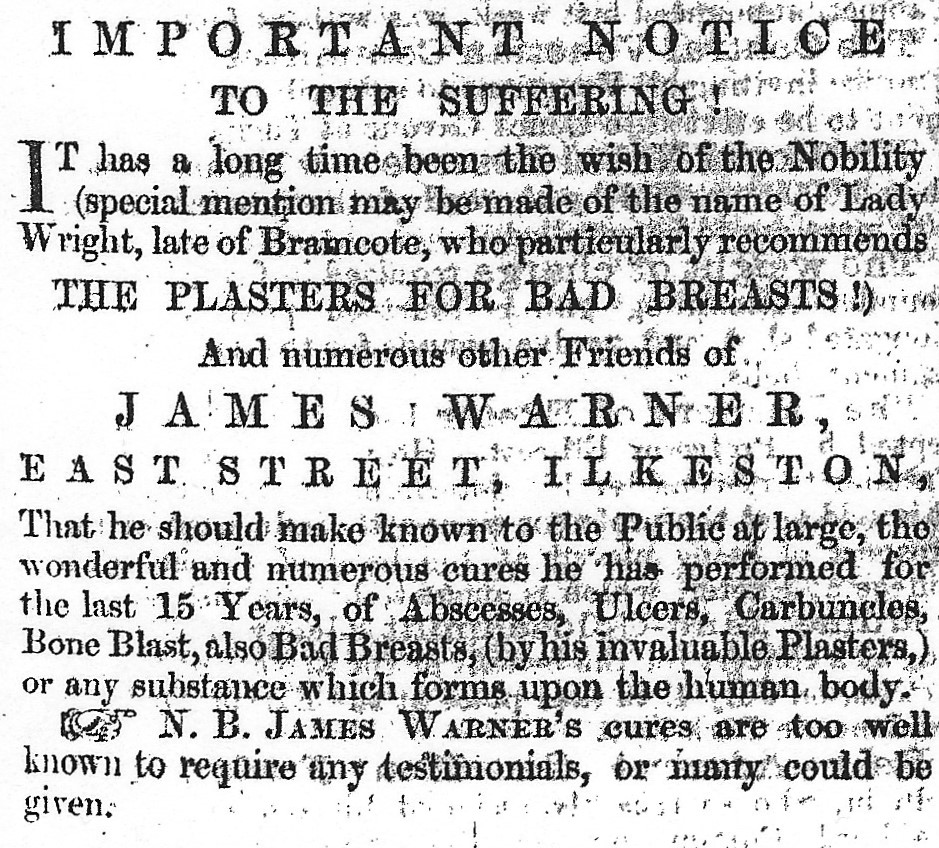

James Warner was never reluctant to advertise his potions and remedies in the local press, as this example from the Ilkeston Leader of June 29th, 1861 testifies….

“Important notice to the Suffering!

It has long time been the wish of the Nobility (special mention may be made of the name of Lady Wright, late of Bramcote, who particularly recommends The Plasters for Bad Breasts !) and numerous other Friends of James Warner, East Street, Ilkeston, that he should make known to the Public at large, the wonderful and numerous cures he has performed for the last 15 years, of Abscesses, Ulcers, Carbuncles, Bone Blast, also Bad Breasts, (by his invaluable Plasters) or any substance which form upon the human body.

N.B. James Warner’s cures are too well-known to require any testimonials, or many could be given”.

Unfortunately James does not seem to have had any remedy to relieve his own discomfort.

For some time in 1867 he had been ailing, and on Saturday evening, May 4th, at about 10.30pm, he moved from his kitchen to the cooler parlour, as he was feeling hot and fainty. Alone in the room he fell out of his armchair and almost immediately expired. He was 60 years old.

Only two months before, his beerhouse and premises, including three adjoining cottages and a parcel of land at the rear, had been offered for sale. But shortly after his death and still in East Street, his widow Julia was now offering to supply the Warner recipes and cures to the people of Ilkeston.

“The celebrated plasters and lotions for wounds, swellings &co. as prepared by the late James Warner of Ilkeston, are now prepared and sold by his widow, residing in East Street, Ilkeston, who will give the most prompt attention to every case brought under her notice”. (IP)

Mystery alert!!

James’s marriage to Julia is elusive. I believe that she was Julia Rason, the illegitimate daughter of Sophia and born in Arnold, Nottingham in 1826. After the death of James, she appears in Nottingham on the 1871 census, living with William Revill whom she later married in 1880, as Julia Rason Warner.

She died in 1900.

Her mother Sophia married Radford-born framework knitter George Taylor in 1844 and thereafter lived her life in Nottingham.

Jim Jeffery is the great grandson of James Mcqueen Rason, born in 1848,the illegitimate son of Julia, and has provided more detail on the family, some of which adds to the mystery if taken as accurate.

Julia Rason Warner married William Revill at Nottingham Register office on October 30th 1880 when she declared herself, a spinster, aged 53, daughter of William Warner (dec), publican.

Jim writes “If you take this at face value then this is not Julia Rason. However neither of these facts sits comfortably with other information we have. They both lived in Union Road, Nottingham at the time and William is described as a ‘Publican’ and Julia has no profession. I also have Julia Revill’s death certificate which is difficult to read but it looks as if she died of ‘Chronic nephritis and Bronchitis’ on 14th January 1900, aged 73. The address looks something like 121 Denison Street (but not sure), Nottingham North West. William Revill is described as ‘Lace Warper Journeyman’. … we cannot (yet) prove that Julia Rason Warner and Julia Rason are the same person”.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Enoch Waters and the Gladstone Angling Society

In March 1868 Enoch Waters took over the Gladstone Inn which was owned by Robert Marshall.

Enoch was married to Fanny Forman, the sister of Catherine, who was the wife of Aaron Aldred, landlord of the Queen’s Head in Bath Street.

Enoch held a licence for selling beer to be consumed on the premises and in August 1878 applied for an in-door wine and spirit licence – not the first time he had tried. At this time he claimed the Gladstone Inn as the oldest beerhouse in Ilkeston, having been established for more than 50 years.

Despite a large number of local residents signing a memorial in support of Enoch’s application, it was refused on the grounds that his premises were unsuitable.

It was probably around this time that Enoch began to reconstruct the Inn, move and expand its premises. The map below (which is fully explained on the next page) is taken from the 1866 Local Board Map and show the site of James Warner’s beerhouse (at PH) … Enoch moved the Inn further towards Burr Lane so that its entrance fronted the lane.

We can see the result of Enoch’s rebuilding on the map of East Street in 1880/81 (again shown on the next page)

Enoch was also a keen poultry breeder and won several prizes at the annual Ilkeston Agricultural Show organised by the Ilkeston Farmers’ Club.

About 1876 he formed the Gladstone Angling Society, headquarters at the Gladstone Inn, with an initial membership of about 14. By early 1881 membership had increased to 60 and by autumn of that year had reportedly exceeded 100.

Membership cost 1s entrance fee plus 2d per week subs.(1882) Season tickets to non-members were priced at half a crown (2/6d).

Enoch had rented part of the Erewash Canal extending from the Gallows Inn (Stenson’s Lock) to the Hallam Fields Lock for his members to fish there. The Canal Company stipulated that Enoch was not to allow Sunday fishing nor ‘netting’, and was not to obstruct or annoy the traders on the canal. As the members were ‘principally very respectable tradesmen of the town who derived a considerable amount of amusement from fishing’ any infringement of the Company’s rules was unlikely to occur.

The Society had also negotiated discount train fares with the Midland Railway Company so that its members could travel more cheaply to Kegworth, Castle Donington, Trent, Lowdham, Fiskerton, Newark, Collingham and Willington to fish there…… something that many had taken advantage of.

The Club’s annual prize-giving one Saturday evening in late October 1881 was preceded by a fishing competition on the Gallows Inn pond when the torrential rain kept competitor numbers down to about 20. The evening entertainment and subsequent meeting at the Inn was better attended and after a most substantial supper supplied by Enoch and his wife the gathering heard that the Society’s finances showed a healthy balance of £10. There were then toasts to the Honourable members, the Town and Trade of Ilkeston, Our National Defences, Our Host and Hostess, and the Chairman and Officers of the Society, each one accompanied by a ‘musical honour’ — a solo song sung by the more musical members (all male). Prizes were then distributed for the season’s heaviest catch of chub, perch, roach, dace and bleak.

There was not however time for the remainder of the prizes to be handed out and these were kept over until the following Monday — they included a copper kettle, a steel spade, a pair of trousers, a bottle of gin, a paraffin lamp, a tea pot, a tin of corned beef and a pork pie.

By September 1882 Enoch had spent over £500 enlarging the beerhouse and tried his luck at the Licensing Sessions again.

The Gladstone Arms was now headquarters not only of the Angling Association but of two friendly societies, and several important licensed victuallers in the town supported Enoch’s application for a full licence.

Once more he went home disappointed.

And he was similarly disappointed in August 1883.

An interesting fact

Enoch’s elder sister Mary married Edward Cox in 1840. Their daughter Ellen befriended the ‘notorious’ George Clay Smith and gave birth to their daughter, Sarah Ann, in July 1861.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Later landlords 1890-1901

About 1890 Enoch Waters retired from the Inn and was replaced by Frederick Lebeter, who got soon himself into a spot of bother with the ‘Inland Revenue’. In 1890 William Thomas Hay, a tax officer, had visited Frederick’s premises and tested his brewing ingredients. He sent off his samples to Somerset House laboratory, and the report came back that too much sugar was being used !! — Fred’s books showed 7lbs was used when really it was 11lbs. Thus he was attempting to defraud the Revenue of a fraction over 5d !!

The case went to the Ilkeston Petty Sessions where numerous witnesses were called, including William Hay, another Government analyst, Frederick’s son George, his brother-in-law George David Knighton of the Nag’s Head (and also a brewer), and Alfred White, the manager at the Star Tea Company in Bath Street, who had sold the sugar to Frederick. The three magistrates put their heads together and decided that there was so much doubt in the case that they would dismiss it.

Fred was married to Emma Knighton (on September 19th, 1897), the daughter of publican Joseph and Sarah (nee England) and was at the Gladstone until 1895 when the licence was transferred to Enoch Jeffries (in July, temporarily, and then in August, permanently). In August 1896 Enoch was refused a licence to serve wine at the Inn.

In May 1897 it then passed to Edward Morris who, two months later, was embroiled in defending himself and his wife in a court case at Ilkeston County Court. His wife, whom he had married on December 25th, 1873, was Hannah Brown, the daughter of John Rawdin Brown junior and Ann (nee Bostock) and thus the grand-daughter of John Rawdin Brown senior and Sarah (nee Beardsley). Hannah was part of the ‘Brown clan of Burr Lane‘, who we shall meet shortly further down the street and whose members seemed very loath to move away permanently from that area. Hannah had just been supplied with a badly-needed set of 28 false teeth for which she had been charged 5s per tooth by the dentist, Samuel Whaley Wing of Wilton Place. Unfortunately they did not fit … or so Hannah claimed. They had been made from a wax impression of her mouth and were a perfect fit, counter claimed dentist Samuel, backed by his 40 years experience. All the parties adjourned into a court ante-room where the magistrate was given a demonstration of how well/badly the teeth fitted but this left him no better informed. The matter would have to be judged by an expert, and so the case was paused until another dentist — Mr Morley of Derby — was able to give his opinion.

Edward Morris left the Gladstone Inn in October 1899 to go to the Travellers’ Rest. To replace Edward at the Gladstone came Henry Hockley, previously landlord of the Needlemakers Arms and then steward of the Liberal Club in the Lower Market Place; the latter was there as the Victorian Age came to a close.

Post script: In 1902 the landlord was William Bell Spencer, son of Hillary and Selina (nee Bell), and whose mother thus had close links with the Travellers’ Rest.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

January 1899: The Derbyshire and Notts Enginemen’s and Firemen’s Association meet at the Gladstone

A new Ilkeston Lodge of this Association was opened on the evening of January 7th when 22 members were enrolled, its aims to obtain a “fair remuneration” for its members, to provide them with legal assistance, and to help raise the standard of skills amongst the workers. The Counties’ Association had been formed in 1892 with 47 members, a total which had now grown to over 600.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Lucy Walls, schoolmistress

Adeline continues her description : “Below Warner’s public-house but still in Burr Lane, and standing close to the road, were two old cottages. (see map on next page). In one lived Mrs. Walls, and her daughter. Mrs. Walls kept a Dame’s School”.

In a letter on Ilkeston Schooling, Adeline describes this school as “opposite the road leading to Hilly Holies, or now the Park”.

“When (Mrs. Walls) died, Miss Walls kept on the school, but becoming unable to pay the rent of the cottage was given notice to quit. She had nowhere to go, and did not know what to do, when some kind friends at the old Unitarian Chapel offered her the use of two pews. As these pews were very large, she had one for her school, and the other she lived in, and by this kind action Miss Walls’ difficulties were overcome. This is perfectly true”.

In 1841 schoolmistress Lucy Walls was living alone in Nottingham Road.

There is evidence that in the 1840’s she moved into one of two cottages standing in a plot of land also occupied by premises later to become the spirit vaults or Wine Vaults. This would place her on the southern side of East Street, adjacent to High Street and could perhaps be ‘the two-roomed cottage at the top of Burr Lane’ mentioned by Adeline earlier.

Both the 1851 and 1861 censuses show her living alone and unmarried at a High Street address. They record that she was born in London about 1793. She may have been the daughter of James and Lucy Walls.

By 1867 she had moved to occupy one of two cottages on the north side of what was then Burr Lane but what is now part of East Street, a few yards south-east of the Gladstone Inn. This would place them just east of the entrance to the Albion Centre car park.

If Adeline is accurate in her description, then at some time Lucy was living with her mother in this cottage.

Writing in the Ilkeston Advertiser (October 1929), Tilkestune remarked on the ‘Pew’ story.

“ ‘The lady who lived in a Pew’ is a find indeed. These box-pews were in the original High Street Chapel, and they are still to be found in some of those old Presbyterian chapels, not merely in towns and cities, but sometimes are even now to be found in rural districts; the latter are very rare. In my wanderings thirty or more years ago I found three or four. One was at Knutsford, where I went to see the town about which Cranford was written by the wife of a former Unitarian minister; another was at Hale, near Altrincham; another was at Ainsworth, near Bolton; and a fourth at Chowbent. Regarding these as relics of the Revolution of 1688, I felt they represented the spirit which produced it. That spirit was, of course, a dissenting spirit. These chapels had box-pews and high pulpits. I consider it remarkable that after a lapse of thirty years I visited a small parish church the other week in an agricultural village, and there to my surprise and pleasure were the old box-pews and the high pulpits of the seventeenth century. One pulpit was for the clergyman and the other for the parish clerk. This church had also not been stripped by the modern restoration imp, and left like a barn with bare stones to chill the heart and the artist in one, but looked adorably white, spiritually clean and wholesome. Here was an antique indeed; white pillars and walls, lovely early English windows with a dense almost opaque glass, contrasting strongly with the dark, almost black, oak pews and pulpits through which the aisles ran like little lanes. My heart leapt at the sight. I was looking at the old box-pews again, the witness to the family worship of seventeenth century Puritans, whether Episcopalian or Presbyterian. There are two churches in Derbyshire I have visited containing box-pews, Alstonefield in or by Dovedale, and Mayfield, some miles lower down. Alstonefield was the church in which Cotton, the Derbyshire poet of the seventeenth century, worshipped. In Mayfield parish Tom Moore lived in a cottage for some time. The churches are well worth a visit”.

Gap alert! As yet I can find no reference to Lucy’s mother.

Sheddie Kyme remembered a small cottage in East Street which housed Miss Wall’s school and which he attended until he was old enough to go to the BritishSchool in Bath Street. “When I was at Ilkeston, about four years ago, I visited Miss Walls’ grave, which is in the North-West corner of Stanton Road Cemetery, and was very pleased to see that some kind friend was keeping the last resting place of Miss Walls in very good condition”.

Lucy died in 1869 and her small gravestone can still be seen in the north-west section of Ilkeston General Cemetery, though no-one is now attending to it personally and keeping it ‘in very good condition’.

The inscription on the stone reads

“In memory of Lucy Walls who died February 19th 1869, aged 75 years.

Ye have in heaven a better and an enduring substance. Heb. x 34”

Tilkestune pondered on this inscription (IA Sep. 1929).

“The quotation … appears to abound in entertaining ambiguities. It is as though the lady’s last thought on earth was that she was going where she would have something better than a box-pew or a brick cottage out of which a fellow human could so ungallantly turn her. We shall all sincerely trust that her hope was realised”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

We continue to examine Burr Lane by looking at the history of the Joseph Knighton Estate which extended over this part of Burr Lane.