Following on from our look at Thomas Jackson, this page examines his family in Ilkeston and elsewhere in England. We only fleetingly follow the relatives as they set sail for America and then establish new lives there. The remarkable website of John Paling and others — The Thomas Jackson Letters — is where you can find detail of these adventurers.

The following outline is composed from local and national records, as well as some detail from the letters collection. It is my interpretation, using that evidence, and thus may contain (many?) errors which I own entirely. If you spot any, or can add to my account, I would be very pleased to hear from you (my email address is on the Home Page)

——————————————————————————————————————–

The Parents of Thomas Jackson

John Jackson (1764-`1844)

In a letter to his cousin Caleb Slater dated May 23rd, 1863, Thomas writes …. “I do not exactly know my father’s age when he died but think he was about 84 and he died in August 1844. I have no record here of the births of my father, your mother or of Aunt Watson. I cannot learn that Watsons have any record of it“.

We don’t learn a great deal about John Jackson, Thomas’s father, from the letters though we do learn something.

“Your mother” (Elizabeth Slater) and “Aunt Watson” (Sarah Watson) were younger sisters of John Jackson, while his third sister, also referred to in the letters, was “Aunt Riley” (Ann Riley).

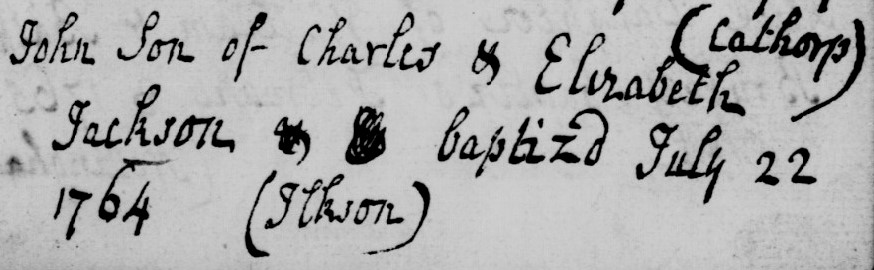

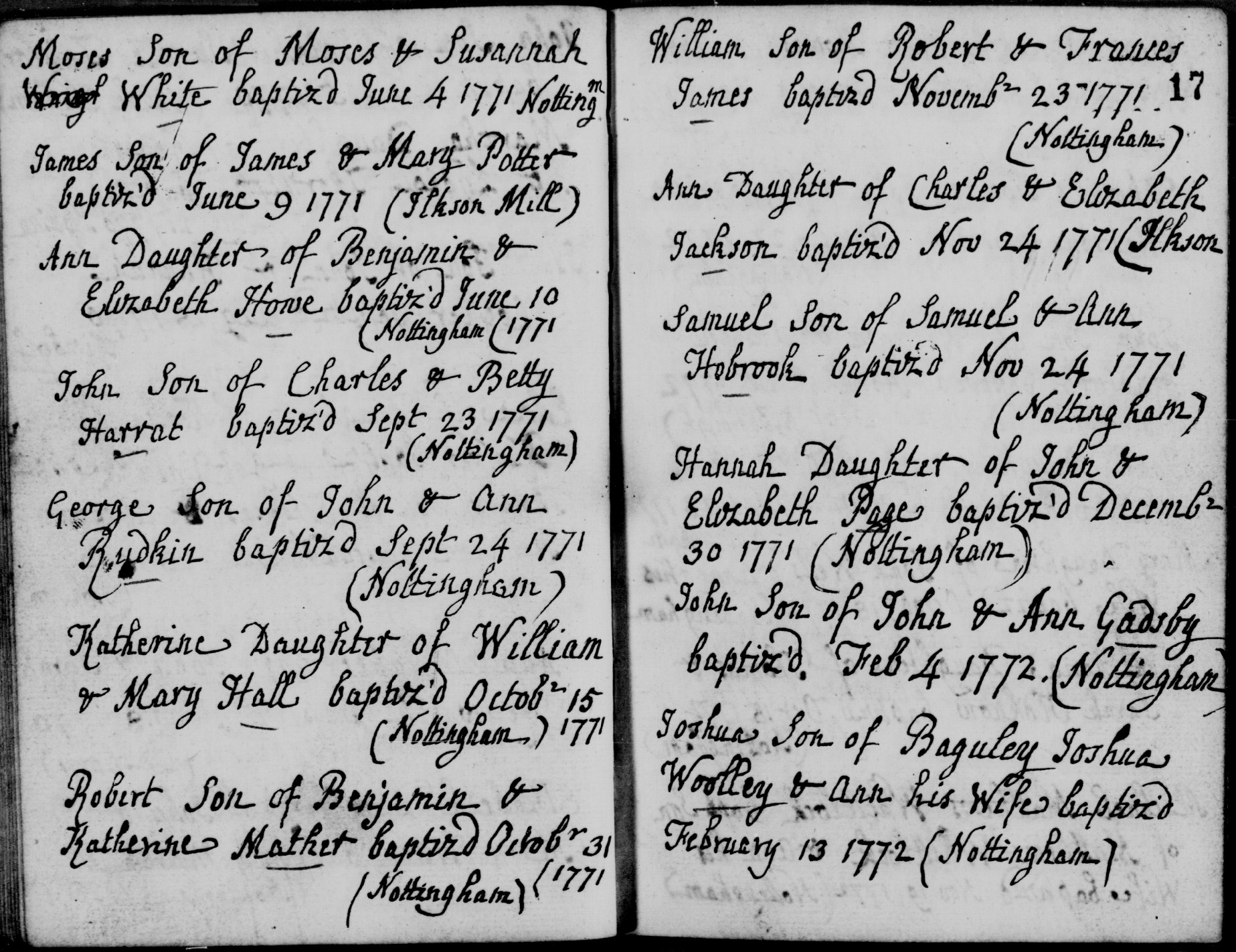

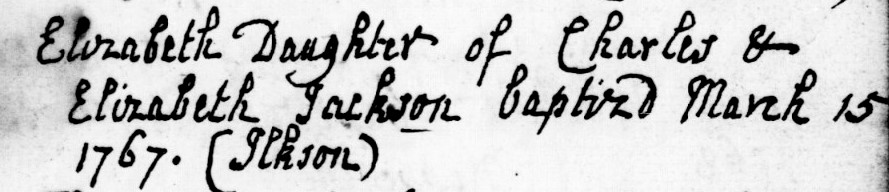

In one letter, dated October 1857 and written by William Slater (son of Caleb), he reveals that “Aunt Sarah Watson tells me that Aunt Riley’s birthday is on 12 November and if she lives till then, she will be 86 years old and her own age will be 81 years on the 14th of the same month”. This would mean that Aunt (Ann) Riley (nee Jackson) was born on November 12th, 1771 while Sarah Watson (nee Jackson) was born on November 14th, 1776. These dates accord almost exactly with the baptisms of two Jackson children recorded at both Ilkeston Presbyterian Chapel and the Parish Church, while the baptism of a third daughter, Elizabeth (later Slater) is given as in March 1767. All are daughters of Charles and Elizabeth (nee Coates) who married at Selston Parish Church on January 5th, 1763. Searching the same Ilkeston records we find that the couple also had a son John, baptised on July 22nd, 1864, at the same Presbyterian Chapel and Parish Church. Thus if the records are accurate and if Thomas’s father John died in August 1844, then he would have been 80 years old at his death. He was buried at Charles Evans Cemetery in Reading, Pennsylvania.

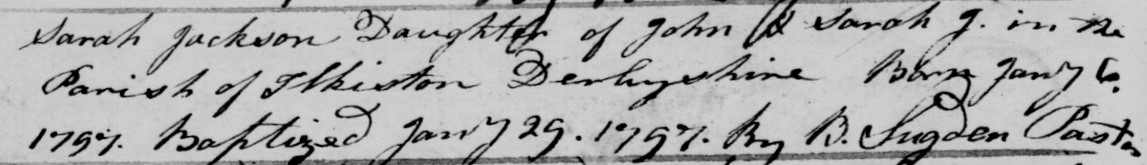

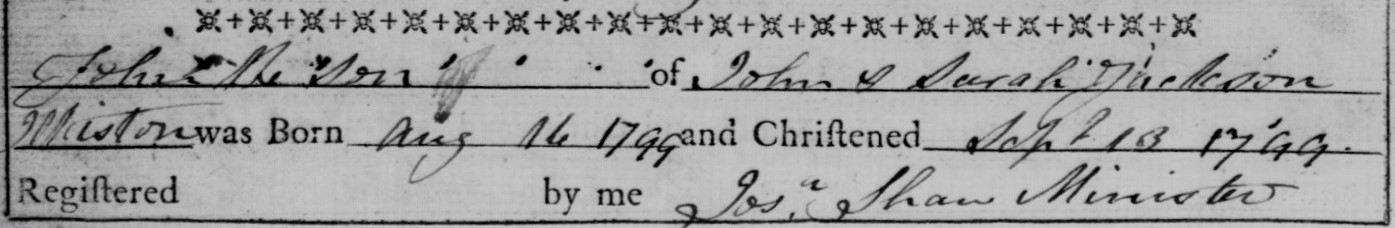

the baptism record of John Jackson at Ilkeston Presbyterian Chapel in Anchor Row

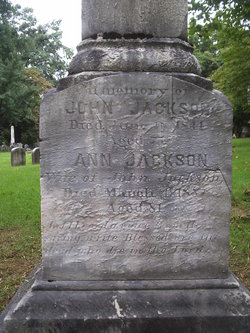

Both images taken from Find a Grave, added by N.D.Scheidt

Father John Jackson seems to have had a close association with the Ilkeston Presbyterian/Unitarian Chapel in High Street, often described as “the oldest nonconformist church in the town”. With sisters Ann and Elizabeth, he had been baptised at that chapel and during the first decade of the nineteenth century he served as one of a group of the chapel’s trustees.

The letters of Thomas do reveal some details of his father’s life before Thomas was born. We can suppose that the oral record of these events was passed on by father to son and is therefore subject to severe scrutiny (and scepticism?)

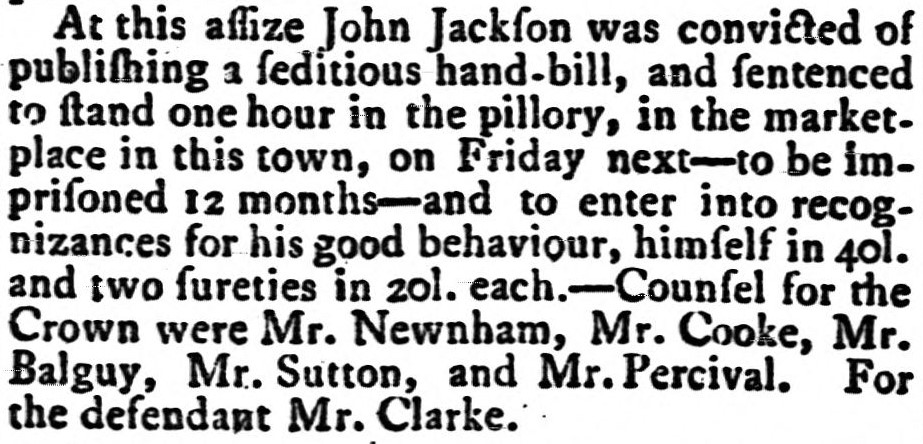

Thomas mentions that his father “suffered a long imprisonment, much hardship and persecution from the government of George the III of England, entirely for his love of liberty”. Elsewhere he explains the reason for this “hardship and persecution“, intermingling it with his own opinions — “The war of the Revolution was a just and brave resistance of Geo. III and his tory government. It was so considered by a large, very large portion of the British people themselves. My father, then a very young man belonged to that liberal party and suffered a persecution of a year’s imprisonment and three times in the pillory for what he spoke and published in the cause of the revolted colonies”. We might believe that father John had perhaps magnified his punishment, if it occurred at all, or that Thomas had embellished his father’s sufferings. However there is supporting evidence of John’s sentence in the pages of the Derby Mercury of 1794 when it describes a case at the Assizes in that town; John would have been 30 years old. (By the time that this article was published in the Mercury, John had already served his ‘time’ in the pillory in Derby market place, and had started his prison term).

from the Derby Mercury (August 14th, 1794)

Shortly after completing his prison sentence, on November 28th, 1796 John married Sarah Levick at Worksop St. Mary (Priory) Church. Within the next three years their two children, Sarah and John (junior) were born, both baptised at Ilkeston Independent Chapel.

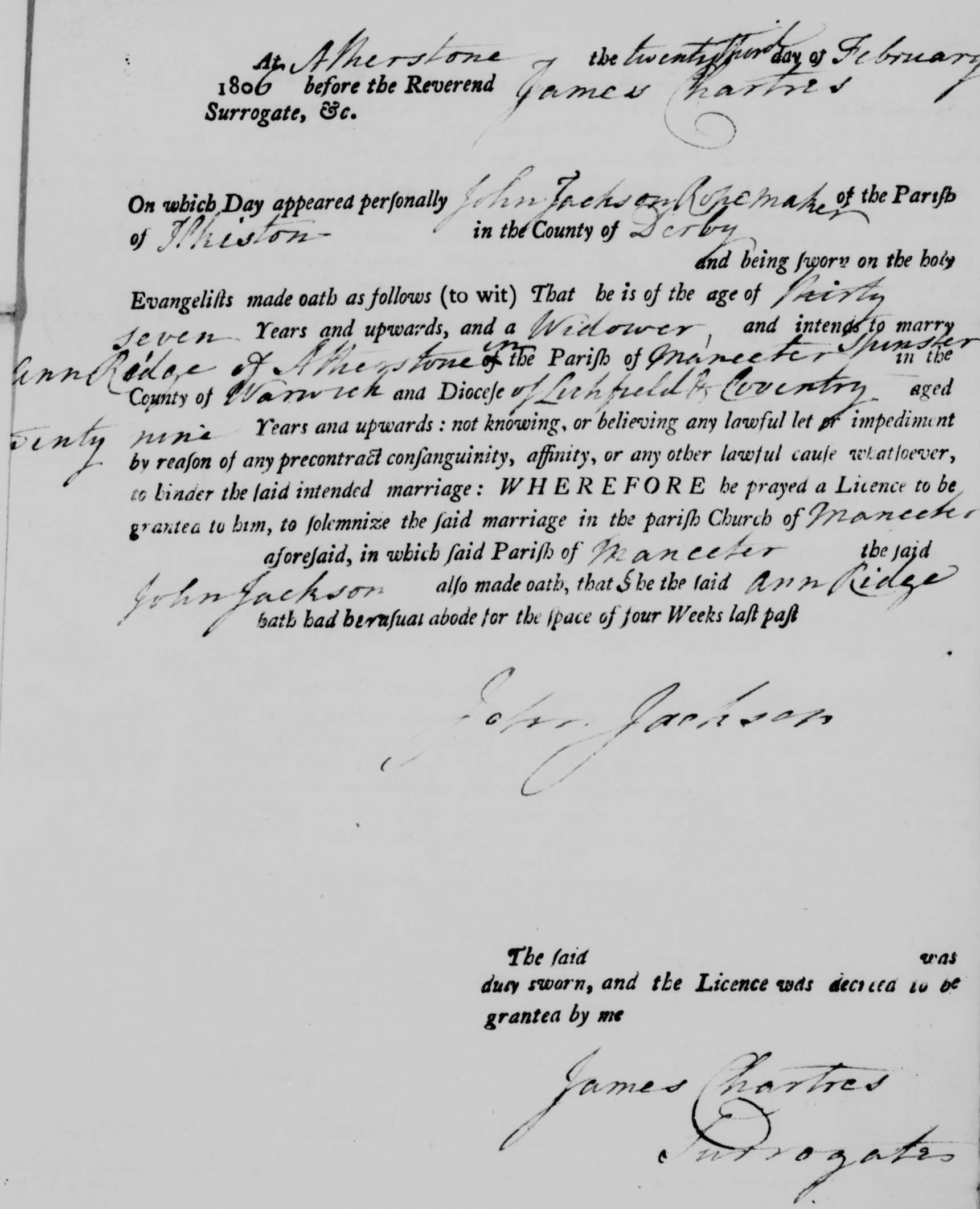

We then find that, on February 12th, 1805, the record of a burial at St. Mary’s Church, Ilkeston of Sarah Jackson, aged 34 — the wife of John ? Leaving John, a widower with two young children ? But not for long. A year passed and John was now ready to remarry, as the marriage bond below confirms.

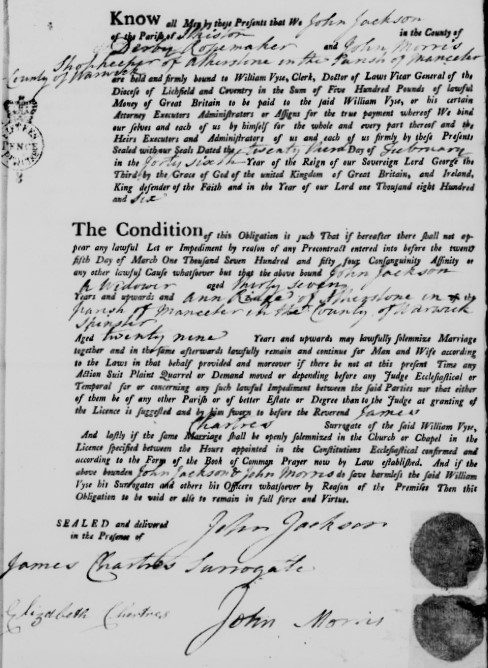

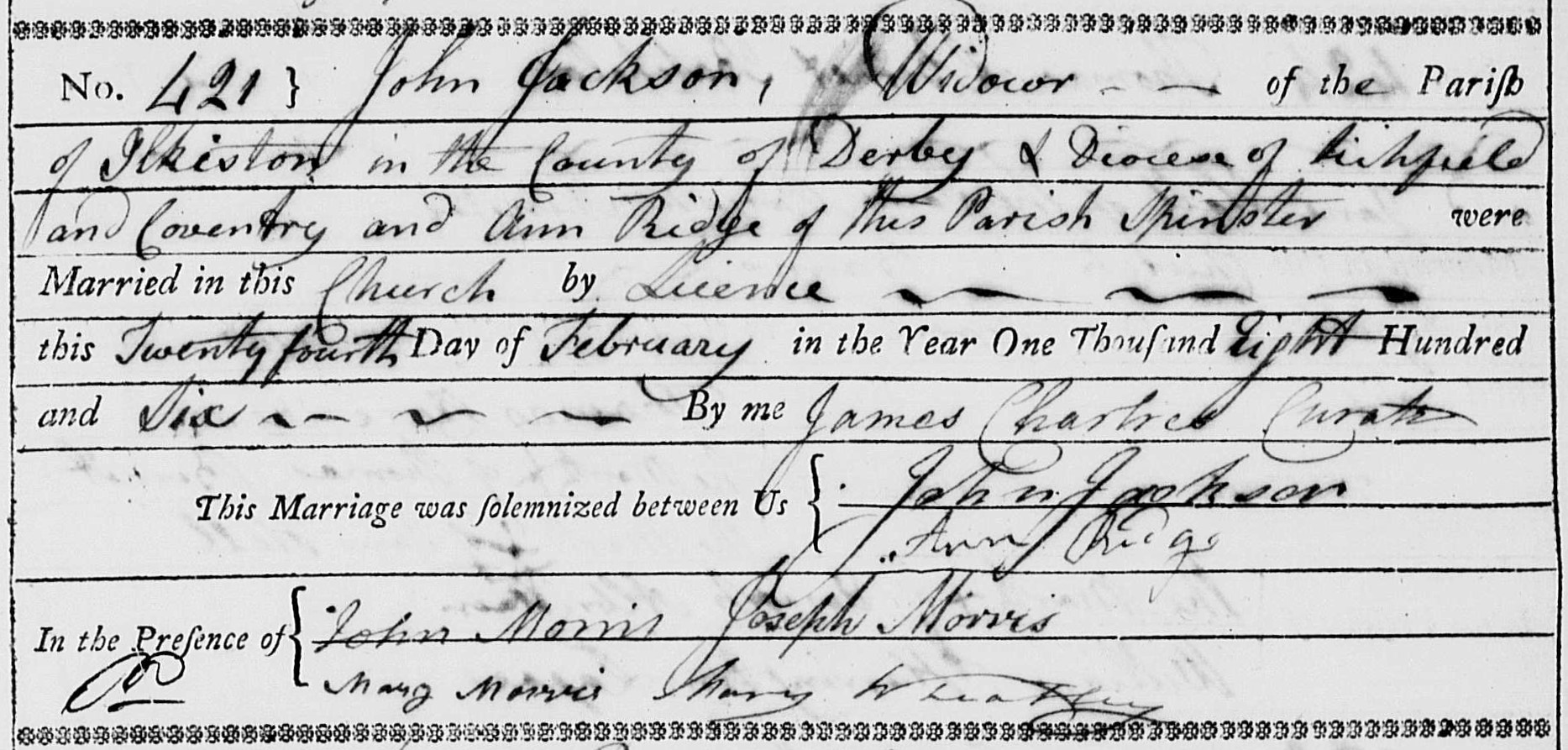

Thus, on February 24th, 1806 John Jackson married spinster Ann Ridge at St. Peter’s Church, Mancetter as the entry below shows. (There was no other ‘John Jackson’ living in Ilkeston at this time, both a widower and a ropemaker).

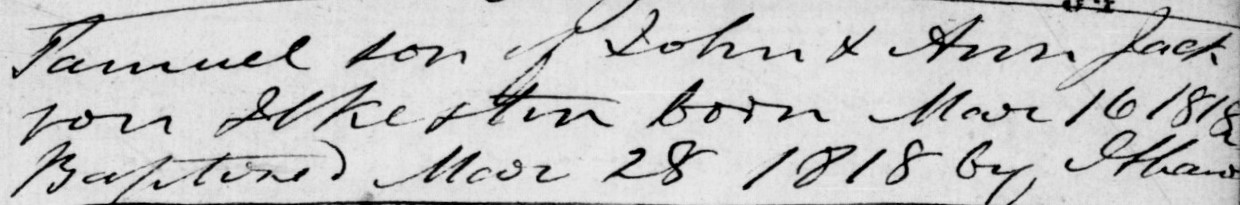

As we have seen, it was in this year that John had taken possession of the old cotton mill premises by the Erewash Canal and was laying out his new ropewalk. And also as we have seen, it was the year which saw the birth of John and Ann’s first child Thomas, the ‘half brother’ of John Jackson junior. And Thomas was followed by five other children, the last one being Samuel born in 1818 and baptised at Ilkeston Independent Chapel (below)

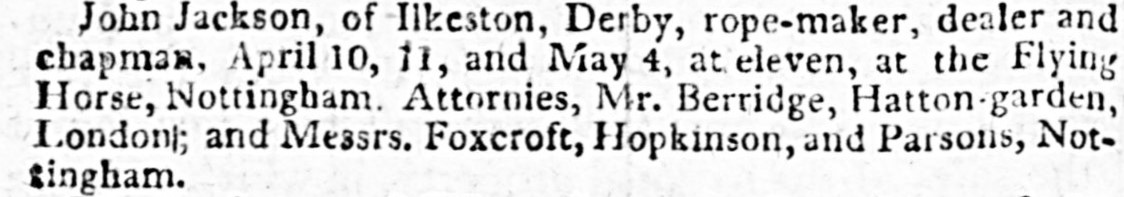

And just before this, yet another misfortune in the life of John Jackson — his bankruptcy is declared (March 1816) —

from the Commercial Chronicle, Lo0ndon (March 26th, 1816)

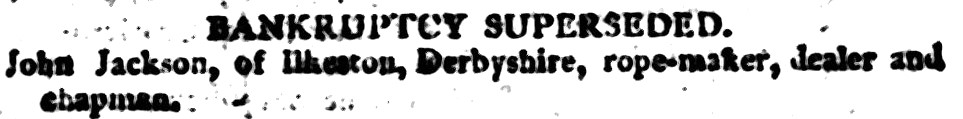

— but is then superseded (May 1816). Presumably John had paid off sufficient of his debts to have his bankruptcy cancelled.

from the London Star (May 8th, 1816)

The term ‘dealer and chapman’ applied to John’s trade in these reports is an interesting one, often cited in bankruptcy proceedings at that time.

‘To make a man a bankrupt, it is necessary that he should be a dealer and chapman, or gain his livelihood by buying and selling . . . mere mechanics therefore, or labourers, who derive a subsistence from their manual labour, cannot as such, become bankrupt; nor can farmers, graziers, proprietors of shares . . . &c. &c. become bankrupts, unless they bring themselves, as dealers and chapmen, within the meaning of the bankruptcy laws.’ From Joshua Montefiore’s ‘The Trader’s and Manufacturer’s Compendium’ (London, 1804).

Off to America …. In 1829 Thomas Jackson left for America, to be followed by other members of the family, including his mother. But what of his father John ?

Thomas tells us that “when I brought my mother and the whole of the family to America, my father was entirely rid of us. But he would not stay rid of us. He did not like the riddence. He followed us to here (to Pennsylvania) …. “

And it looks like father John landed in New York in 1833, aged 68, aboard the “Silvanus Jenkins” (below, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1897).

“…. and we made his last years comfortable and laid him to rest where his dust now reposes with my mother, my brother Sam, two of my children and one of my grandchildren ?”

John Jackson died at 79 years of age in June, 1844 in Reading, Berks, Pennsylvania where he lived for many years prior to his death. (His grave monument in Charles Evans Cemetery, Reading, Pennsylvania, is shown at the top of the page).

Ann Jackson (nee Ridge) (c1776-1857)

In 1856 Thomas wrote that “my mother is now over 80 years old and is very feeble and infirm. She had a sort of stroke about eighteen months ago and has been in a very poor state ever since. This winter seems to be very hard on her. She has been keeping her bed about 2 months and we never expect to see her up anymore. She has no pain though. None at all. Only weakness and slowly sinking to the grave under the weight of years and the exhaustion of natures vital powers. But she is well of and well taken care of in her old age. Mary and her have been living together a many years & now one of the sister Ann’s daughters is with them to help to take care of her grandmother“.

Ann Jackson (nee Ridge) died on March 4th 1857, aged 81, and was buried with her husband. (see above)

——————————————————————————————————————–

The siblings of Thomas Jackson (i.e. the children of John and Ann Jackson)

In January 1872 Thomas wrote that “of the six children of my Father that left England nearly Forty three years ago, five is still living and all, except from myself in tolerable good health and comfortable“.

There is no better place to discover more about these children and their lives in America than the excellent website, meticulously compiled by John Paling and his associates and featuring the letters of the Jackson family and relatives. Here are just a few ‘clippings’ from the letters, all written by Thomas …

Ann (1808-1888) …. 1863-1871 Ann lives at a town called Scranton, about 140 miles North of here (married to Francis Shilston). She is comfortable and all her three daughters married. The oldest one Matilda died last winter in childbed of her first child. Poor Ann has had rather a hard life of it. But she is now comfortable in her old age”

“1871 .. She is Grandmother to half a dozen youngsters. Her youngest married daughter was down here on the visit last summer, with her little boy”.

Edward (1810-1896) … “1863 Edwd. Is keeping store in Reading”. And then in May 1867 he was “well & lives in Reading. He is married again to his first wife’s niece and is doing well. He has no children. Never had any”. And towards the end of his life (c1894) Edward recalled that “my late brother Thomas and I came to this country from Staffordshire, England in 1829. We were rope makers by trade“.

Mary Ridge (1810-1880) …in 1856 “Sister Mary is still unmarried and does little else than take care of her mother“. And after the death of her mother “May 1863 Mary is with some friends in Phila“. However by May 1867 “my sister Mary is a childless widow and lives on small income left her by her husband“.

Then in February, 1871 “Mary has had weak eyes from childhood and they are now failing so fast that in a few months we fear she will be quite blind. But she is provided for if that does happen so unfortunately“.

And in October 1874 “Mary, many years a widow and over 60 years old has been lying low with fever at our cousin William Watson’s, where she was visiting, but is now better“.

Henry (1814-1896) …. “May 1863 Henry has a rope walk at Harrisburg” and later “May 27th 1867, my brother Harry has a small rope walk at Pottsville, 35 miles above here and is quite comfortable. He has been married over 20 years and has children grown-up”.

And then “Oct 1874 My brother Henry, a stout hearty man of about 60 is here with me at present“.

Samuel (1818-1852) … ?

——————————————————————————————————————–

The aunts and cousins of Thomas Jackson

In his letters Thomas Jackson mentions three married aunts, some of his uncles by marriage and several of their children.

Aunt Riley (1771-1861) and family

This ‘poor old woman‘ was born Ann Jackson, the second daughter of Charles and Elizabeth (nee Coates), in 1771.

Ann was also baptised at Ilkeston’s Parish Church on November 12th, 1771. In one of his letters, dated October 1857, William Slater writes that “Aunt Sarah Watson tells me that Aunt Riley’s birthday is on 12 November and if she lives till then, she will be 86 years old“, which accords with these Parish records.

On December 26th, 1795, also at St. Mary’s church, Ann Jackson married Isaac Turton, a stockingweaver, and the couple had at least eight children together. Gauntley’s Survey of Ilkeston copyhold property in 1817 shows this Turton family living adjacent to the Sir John Warren Inn, just around the corner in Pimlico. (Were they in the premises previously occupied by Charles Jackson and his family — see next section).

By 1823 Ann was a widow — what had happened to Isaac ? — and she was ready to marry again. So, on January 20th, 1823, she married widower Francis Riley, an agricultural worker, originally from nearby Trowell, and the couple continued to live in Pimlico for many years.

Francis died on January 18th, 1855, aged 82, and towards the end of her life his widow Ann was living in Stanton Road with her daughter Ann junior and her family. This daughter Ann Turton, had married lacemaker George Carrier on July 24th, 1830, at St. Mary’s Church and thereafter had always lived in close proximity to her mother.

Ann Riley is referred to as blind in one ‘letter from America’, dated 1856 and in that year Thomas Jackson wrote to his cousin Caleb Slater indicating that “poor aunt Reiley is still alive and gone blind with old age. And also very poor. I wrote to my cousin John Watson about her and proposed that her nephews here in America should send her something to help her along and make her a little comfortable this winter. There are six of her nephews here. Three of us & three of Watsons” (edited).

In the following year (May 1857) Tillie, Thomas Jackson’s daughter, wrote to Caleb (her first cousin once removed) stating that “I write to include you a draft for £2.5.) which has been contributed towards the support of our Aunt Riley by her nephews in America, to buy her any little comforts that her great age may require and that she might not otherwise obtain. Although I have no doubt you and your family are very kind to her, yet my father thought her nephews in America might help her too. It is our purpose to continue these remittances from time to time as long as the poor, dear old lady lives. And as we know you to be the kindest friend she has, we shall we shall always send them to you”.

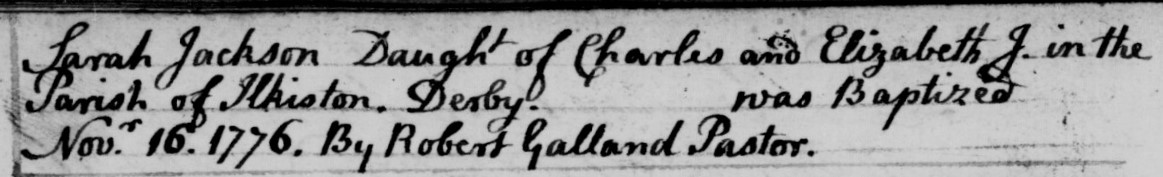

Sarah’s baptism in the records of Ilkeston Independent Chapel

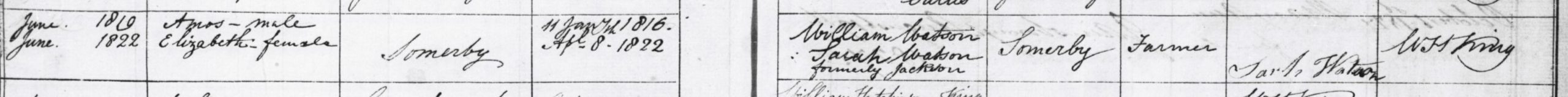

She married William Watson on December 12th, 1799 at Annesley All Saints Church, Nottinghamshire. Several of their children were then born at Whatton, Nottinghamshire before the family went to farm at Somerby, Lincolnshire, where son Amos Charles (1816) and daughter Elizabeth (1822) were born (below)

from the baptism records of Caskgate Street Independent Chapel in Gainsborough, Lincs

In the late 1830s many of the Watson family, including sons John, William and Amos, left England to settle in New Jersey as farmers, never far (relatively) from their Jackson relatives.

In June 1856 Thomas Jackson wrote that he “fetched Aunt Watson over to see us and stay with my mother awhile. She stai’d with us about 6 weeks and seemed very well and hearty for a woman of 80 years old. She has still a good head of nice black hair. Not a gray hair in it“. A grandnephew, William Slater, was similarly impressed by Sarah in October 1857 and wrote “Aunt W is very active and can set out to the table and preside also at the tea department as well as anyone need wish. She is rather short, her hair is black with only a very few gray hairs in there on her forehead and very smooth and almost without a wrinkle“. She had three sons then living in America — John, William and Amos — all with wives, and a collection of eight grandchildren. William Slater added (December 1857) that “her home is principally at John’s at the old Homestead she goes occasionally to see her other two sons and stays a few weeks mending their stockings or what else she can find for to do. She will always have some thing to do“.

A couple of years before Aunt Sarah’s death in 1861, Thomas Jackson wrote in glowing terms about her: “She was and still is, the same thoughtful, kind hearted & anxiously affectionate aunt that she always was, ever since I knew her first at Kirkby Woodhouse full five and forty years ago. She is still a wonderfully active woman for her age & old as she is, has still a fine beautiful head of hair, with scarce a gray one in it. … When I saw her last it was a few weeks after John Watson’s wife died and Aunt was then and is now, taking all the care of his household upon herself. She talked much of her sister Riley and so wished that they could be together and die together. A very solomn but a very, very, beautiful idea. For two sisters to pass their girlhood together and then, after sixty, over sixty years of seperation, and going through all the trials and varied scenes of life that they have, to come together again and make their home under the same roof, there to comfort and cheer each other, and renew afresh all those fond and affectionate endearments that their hearts and feelings delight in, would indeed be a very great gratification to them. Really if I were to come to England this summer I should feel very much like bringing Aunt Riley back with me, if she could bear the voyage, only to be repaid by the great satisfaction of seeing these two good old souls together once again. But I fear it cannot be. Whether I shall ever see my dear dear native land again or not, is, I think very very uncertain. It seems as if something was always to happen to hinder me. But it is of no use to repine. The never ceasing round of toil & care cannot be avoided & the battle of life must be fought as long as this life lasts. Of all this you are as fully aware as myself“. (edited). He later adds that “she is the only one of my Father’s sisters here. & her and Aunt Riley are the only Aunts I have on earth“.

Cousin John Watson

John was farming in Piscataway, New Jersey and in June 1859 William Slater reported that John’s “farm and crops look in first rate order he says the land is just as good as the farm they had in Lincolnshire if the climate was as good as it is in England he could raise as much wheat and of as good quality he has a fine team of horses & a lot of good cows and I think his crops of wheat look better than any I’ve seen in that neighborhood“.

By 1862 he was married for a second time and by 1875 wrote that brother William was well while brother Amos was “much afflicted with chronic rheumatism, very lame aparently incurable still able to sit at his desk attending to his books: too much credit and too slow pay“.

In 1872 Thomas Jackson summarised the progress of the Watson lads in America thus — “I saw John & William & Amos Watson and their wives and families last summer. They were all well and well off. John has only one son, a nice steady young man who would not be a farmer like his Father. So John sold his farm and retired to a nice quiet village to live out the rest of his days on the interest of the money and his son Charly is a good house carpenter.

About seven years ago John married an old maid of about 60 and they seem to be a very comfortable cozy old couple well calculated to smooth each others downward path to oblivion, or to “another and a better world than this”. I am seven years (?) younger than John Watson, but I have no notion of marrying an old maid or a young one either”.

—————————————————————-

Aunt Slater (1867-1805) and family

The eldest daughter of Charles and Elizabeth Jackson was Elizabeth, and like her sister Ann, she was baptised at the Old Meeting House of the Unitarian/Presbyterian Chapel in Ilkeston’s Anchor Row, followed by a baptism at the Parish Church.

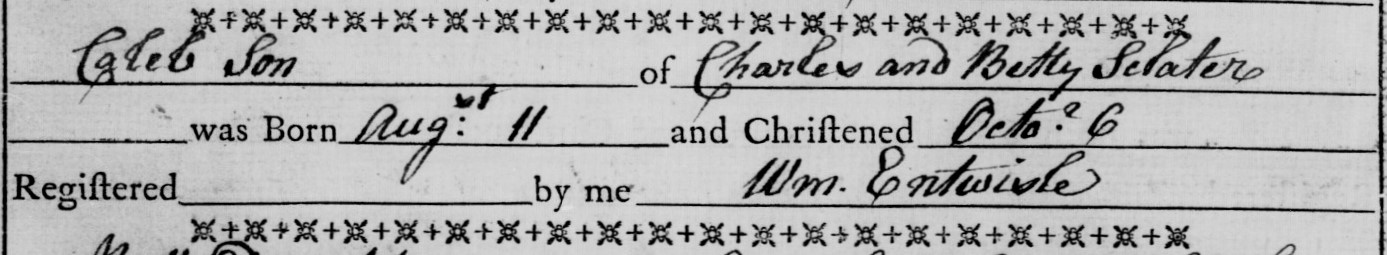

Son of Charles and Elizabeth (Betty) Slater, Caleb Slater was born on August 11th, 1789 and baptised in that year, at Ilkeston Independent Chapel in Pimlico. All of his adult life was lived in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, where Caleb worked as a ropemaker.Throughout the letters collection Caleb and Thomas Jackson are correctly referred to as “cousins”, as Caleb’s mother and Thomas’s father were siblings. The same letters show that, despite disagreements, there was a very close bond and admiration between the two men. For example, in 1860 Thomas wrote to Caleb’s son, William … “Do you know that for the last 30 years of my life, the example of your good Father has been of the very greatest advantage to me. I knew your Fathers history from the start. He settled at Langly mill and started his business life with but little to begin with. For forty years he has made the very most of his means and fought the battle of life like a brave man, with the most unflinching firmness and praiseworthy perseverence, giving his mental and physical powers to the attainment of his objects with an energy & a will that could not fail of success. Many a time in bygone years, when I met with losses, difficulties and vexations in this far off foreign land, has my mind gone back to your Father at Langly mill, and the thought that he could hold his own & make headway there, has filled me with more firm determination to stick to the one spot and “put it through” in spite of every obsticle or misfortune that came in my way. And so here I am yet, sticking to it as close as I can and most likely shall continue so to do untill I am full as old as your Father now is, if I should live so long”.

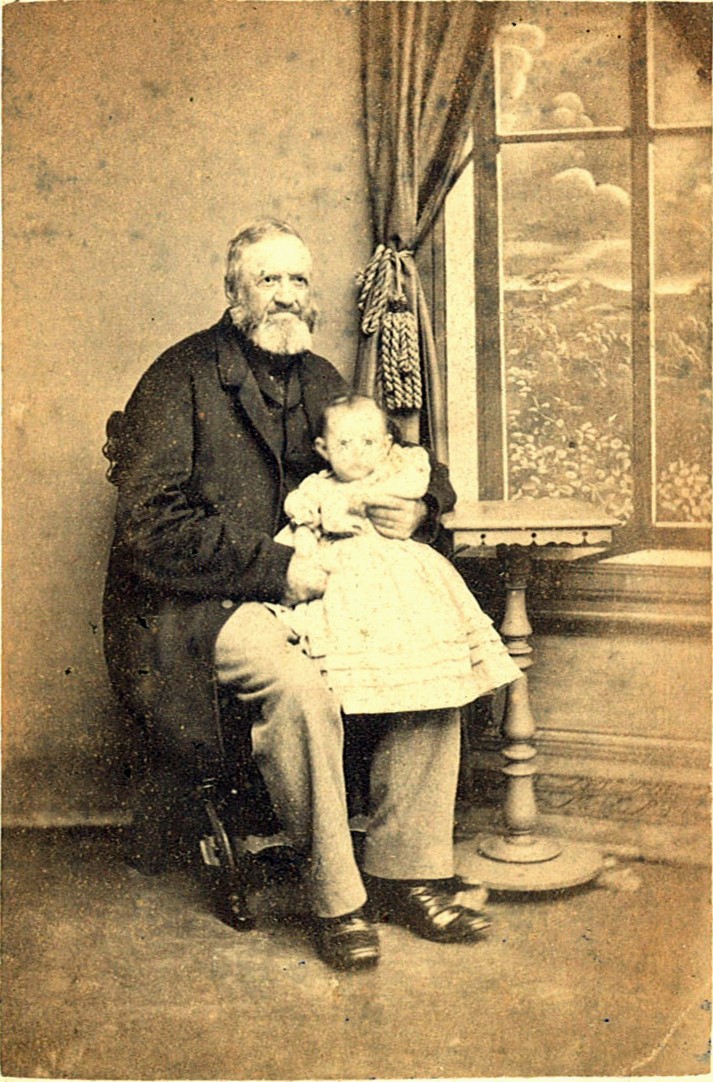

Caleb and his grandson Charles Lincoln Slater, son of William and Ann (nee Coates)

In a further letter of 1867 Thomas wrote … ” I learn that you are now 77 years old and rather poorly. I ought to have written to you long ago, and now I am very sorry for my long silence. I must beg your forgiveness and hope I shall have it and a long letter in reply to this. I ought to have spared time to write to you if I only a few lines. But indeed I have been very very busy”.

Despite the fact that Caleb was ‘rather poorly‘ he did live on for another ten years and died in Eastwood on August 13th, 1877, aged 88.

Caleb’s son William (1828-1900), Thomas’s first cousin once removed

On several occasions Thomas wrote to William Slater who, in the 1850s, went over to America to work with Thomas at Reading. The latter described William as his ‘cousin‘, making no distinction between ‘first cousin‘ and ‘once removed‘ etc. Thus in one letter (1858) he had “been counting all my cousins here and I found there is 41“.

After William returned to England about 1860, Thomas kept abreast of his fortunes. He noted (1867 from John Watson) that William was married and had moved to Darlington. “No doubt he has got a good wife & will be happy. I wish him very very happy and very well. I intend to visit you all before very long. I would have come this year but I am to busy and have too much to do“. This would have been Ann Coates, the first of William’s three wives, whom he married in 1866 at Moor Green Congregational Chapel in Greasley. Sadly she died in 1868, having just given birth to a son, Charles Lincoln Slater. Thomas was very sympathetic; — “I heard of his marriage and .. I heard of his sad bereavement and my own experience of 28 years ago taught me how to feel for him and sympathize with him most truly. Such is life. High hopes and lowering fears. Bright prospects, great expectations, sad, very sad”.

For significant periods Charles Lincoln was nurtured by his two unmarried aunts Sarah and Mary Slater.

Finally, we need to have a look at Thomas Jackson’s half-brother, John Jackson junior who had been born at the Rope Walk in 1799.