Adeline is now walking on up Bath Street and past the shops of Joseph Carrier. There she finds that “Mr John Wombell, printer and stationer, came next, and it was here that the ‘Ilkeston Pioneer’ was launched on July 1st, 1855.” (Slight mistake !! It was in fact January 1st, 1853)

Well of blackness, all defiling,

Full of flattery and reviling,

Ah, what mischief hast thou wrought

Out of what was airy thought,

What beginnings and what ends,

Making and dividing friends !

Mary Elizabeth Coleridge .. The Contents of an Ink Bottle

The Ilkeston Pioneer is born.

One of the first intimations that Ilkeston was to enjoy its own periodical came in the Derby Mercury of October 27th 1852 when the editor replied to a message he had received from ‘a correspondent’ (John Wombell perhaps ?!) …

….. he stated ‘We must know more of the nature and objects of the projected ‘Periodical for Ilkeston’ before we can commit ourselves to the laudatory recommendation which we have received from a correspondent, with whom we have not the pleasure to be acquainted’.

A day later and the Nottinghamshire Guardian was less circumspect; it rejoiced to hear of a new cheap, non-political monthly periodical to appear in Ilkeston.

“Its aim will be the elevation of the masses, by endeavouring to create amongst them a taste for reading and mental self-culture”.

The Ilkeston Pioneer and Erewash Valley Gazette began its life on January 1st, 1853, as a ‘monthly’, published by John Wombell from his Bath Street offices and priced at 2d.

It proclaimed itself as a “journal of literary and scientific entertainment and instruction, and of local and general news (and general mining information)”.

Its front page quoted from (sic) “Shakspere: “ignorance is the curse of God, Knowledge the wing wherewith we fly to Heaven”. (Henry IV Part 2).

After the Pioneer’s first issue the Nottingham Review assessed its merits:

“The first number of this candidate for public favor is extremely creditable. Its literary merits are superior, and its typography unexceptional. We wish the editor a long and prosperous career of usefulness”.

By its third issue it had a circulation of 1000. (NR 1853)

Just over a year later, on April 27th 1854 (Thursday), the Pioneer became a weekly newspaper and continued thus* until its last issue on March 23rd 1967.

*There was, however, a short period from September 1854 until April 1856 when publication was halted. The beginning of this hiatus was noted by the Nottingham Review;

“The Ilkeston Pioneer is no more. Its decease was very sudden; no announcement and no sign of its approaching end was visible; the only means of ascertaining any information of the crisis was that it was not forthcoming on the day of publication. It is stated that it will not be resumed, at least for the present”.

The reason for its temporary closure might be connected with the editor’s complicated domestic circumstances.

(See the following sections, noting the birth years of his children, both legitimate and illegitimate)

John retained ownership of the paper for almost 35 years.

Subsequent owners were Cornelius Brown of Newark (four years), the Ilkeston Pioneer Printing Co. Ltd. (ten years), and in 1902, Edwin Trueman, whose connection with the paper dated from 1862.

John Wombell and family.

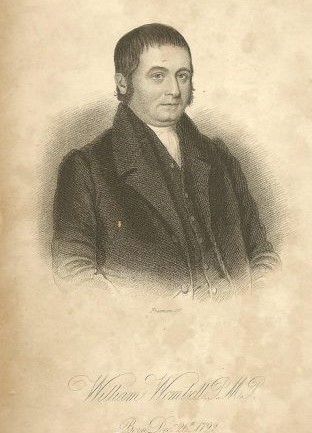

Born in 1818, John was the eldest son of the Rev. William Wombell, Primitive Methodist minister of Wellow, Nottinghamshire, and Mary (nee Woodward).

John’s father was the illegitimate son of Ann Garland and was baptised as such in December 1792 at Kneesall, Nottinghamshire, where just over a month later Ann married James Wombell (father of the child?).

Both William and his wife Mary were buried in St. Mary’s churchyard extension with John’s brother James.

“Mr. John Wombell, his wife, two daughters and one son lived on the premises”.

John Wombell married Susannah Gover, daughter of Dorset-born seaman John and Susannah, in 1838 at Grimsby, Lincolnshire where her family was living. Shortly after, the couple moved to their Bath Street residence, where the Erewash Valley Printing offices were established in 1840.

Their children were Susannah Mary (1843), Emma Gover (1844), John Garland (1849), and William Woodward (1852). There was also one unnamed daughter born in 1857 but she survived only 10 minutes.

The Derbyshire Record Office holds minutes of various meetings and reports of the Primitive Methodist Circuit based at Ilkeston from 1839. Some of these show that in the late 1840’s John was accused by the leaders of the Primitive Methodist church, of which he was a member, of a scandalous ‘dalliance’ with fellow member Maria Beardsley.

Apparently John had kept the company of Maria and paid her particular close attention. The couple had sat together in chapel, walked out together arm in arm and John had visited Maria’s family home.

Maria lived in Middle Road, Ilkeston and was about 17 years old at this time.

Despite requests from the Methodist Circuit Committee to desist from this liaison — which was bringing shame and embarrassment on the chapel and was contrary to its Connexional Laws — John refused.

The relationship continued and seemed to involve more than just holding hands.

Therefore and in acrimonious circumstances John was expelled from the Church in 1851. And one of those involved in this action was builder Thomas Shaw, a teacher and preacher in that church. We have seen how John and Thomas were subsequently opposed over the ‘PigstyPark affair’ of 1861-62. And Thomas was neither the first nor the last person to cross swords with the printer, who would often use his influential position as editor of the main local newspaper to press home his point in any argument.

You might be interested to know that I have the original leather-bound minute book for the Primitive Methodists (their chapel was on the corner of Burr Lane/Chapel Street at that time). My great great great grandfather, John Robinson, was the secretary. The minute book also notes accusations against John Wombwell of having stolen the chapel’s silver and makes threats of what they will do if he doesn’t conform. No wonder they were known as ranters.

This incident is discussed in the next section.

At the death of Paul Walker in March 1851, John was appointed postmaster in his place. Almost immediately he was granted permission by the Postmaster General to open a money order office in the town.

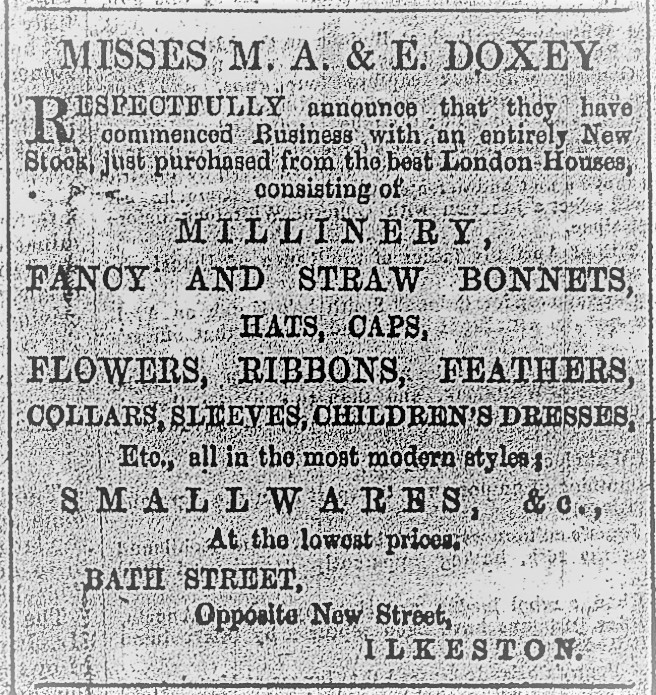

John moved from his Bath Street offices to alternative ones in the Market Place early in 1859 and a few months later milliners Misses Mary Ann and Elizabeth Doxey moved into the vacated Bath Street premises of the Pioneer. They previously occupied Bath Street premises opposite New Street. (see below* The Doxey School). At this time the Post Office was transferred to Richard Potts in South Street.

John was temporarily declared a bankrupt in May 1862.

The newspaper proprietor was the first clerk to the Ilkeston Local Board after its formation in 1864, and remained in that position until the ‘election crisis of 1869’.

In that year — and overlooking the Derby Mercury, The Nottinghamshire Guardian and the Leicester Journal — John was modestly promoting the Ilkeston Pioneer as the chief representative of the Conservative Party in the Midland Counties.

John is sued … not for the first time … nor the last !!!

In July 1867 it was reported that John was being sued in Belper County Court by reporter Richard Allison for £2. Setting aside the seeming insignificance of this case, it is illustrative of how national and provincial newspapers operated at this time.

Richard was what one might describe as a freelance journalist, working part of his time for the Nottingham Daily Express, supplying that paper with accounts of Alfreton Petty Sessions and district news. John had printed Richard’s reports into his own newspaper, and the latter had thus written to John to ask for payment of 10s per week for the use of his work … John had ignored the letters. The bill was now for four weeks, and hence the case before the court.

John’s solicitor argued that it was the custom of the profession to copy each other’s news, and that, once they had appeared, the reports were not the property of the writer but of the newspaper’s proprietor. Several editors and proprietors had attended to support this claim … but the judge didn’t need them. He stopped the case. He referred to the owners of the London Times who had previously claimed that as soon as their paper was published their news was telegraphed into the provinces, and circulated by the penny daily newspapers before the original papers could get there. There was no doubt that as soon as news was published, the articles were public property.

Richard had lost his case and was ordered to pay costs and court fees amounting to about £6 !!!

John takes a holiday

In August 1867 John’s displayed his ‘kindness towards his employees’ with a summer treat – a day trip to Grimsby and Cleethorpes, an area with which he was, of course, familiar.

The company left for Nottingham at 2am and there caught the mail train to Grimsby at 3.50am arriving there at half past seven.

After an ‘excellent breakfast’, John “readily consented to act as “guide” to the excursionists, and took them around the docks, thoroughly inspecting the shipping there before a bracing walk along the sands — packed with hundreds off visitors enjoying the ‘invigorating sea breeze” – and on to Cleethorpes.

A dinner at the ‘Dolphin’ was followed by an afternoon on the beach, though a rough sea precluded a boat trip.

After a substantial tea the day-trippers were on their way home, arriving in Ilkeston at 11pm.

“The day was thoroughly enjoyed by every one, and the liberality of Mr. Wombell was highly appreciated”. (IP)

This was shortly before the Pioneer moved from its offices in the Market Place to other offices in the Market Place, a few doors away and closer to the new Town Hall.

The reason? To provide more spacious accommodation for the increasingly popular newspaper with its growing readership.

In 1867 it boasted a circulation of 5000.

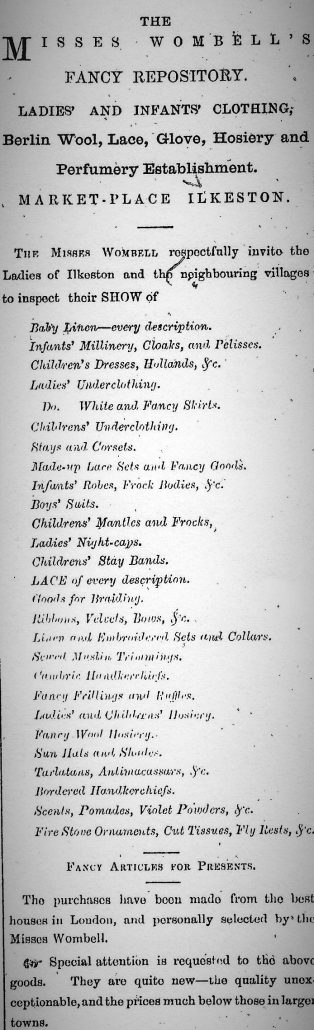

Also at this time John’s daughters, Susanna Mary and Emma Gover, were trading at their ‘Fancy Repository‘ at this Market Place site (right)

John retired from the Pioneer in 1889 and shortly after the death of his wife, Susannah, in September 1889, he left for Belper and then Ashover.

In March 1891 the Wombell premises in the Market Place were put up to let (after March 25th ?) .. they were described as …..

“a spacious shop, modern front, plate glass doors and windows, large drawing room with plate glass windows and Venetian blinds, breakfast and dining rooms. kitchen, capital cellerage, washhouse, five bedrooms, store and other rooms, conservatory, large TWO STOREY WAREHOUSE (ten windows) with all convenient out-offices), stable (two stall), hay chamber, carriage house, and cart-shed; also a snug COTTAGE (four rooms), and the large GARDEN stocked with young fruit trees….

…. in a prime location, with an abundant private supply of hard and soft water”

It appears that stationer and printer Andreas Edward Cokayne occupied the shop at this point and at least for a short period of time. The copyhold cottage mentioned in the advert was in Burns Street, at the rear of the shop.

In February 1895 the Market Place business premises of John Wombell were put up for sale…. at this time being occupied by solicitor Charles John Jackson and Charles James Marson, dyer and cleaner.

A final bill to pay: December 1895

Although John had ‘escaped’ Ilkeston, he had not escaped people who thought that he still owed money to them. And one of these was joiner and builder William Richards of Cotmanhay Road. (son of Samuel and Martha (nee Mellors)).

In December 1895, William pursued his ‘debt’ of nearly £26 into Ilkeston County Court where he reckoned that John, in absentia, had employed him in November 1889 to do some repairs on his Market Place premises. John had already departed from Ilkeston (in September) to live in Belper, but had left instructions with his ‘agent’ Thomas Floyd of Mount Street. Thomas had had a long relationship with John, being his servant for over 12 years before John’s departure to Belper, acting as his groom and gardener. In October 1895 it was Thomas who had shown the builder around the property, pointing out what work needed to be done; and after the repair work had started, John came over from Belper to see how it was progressing. Evidently he was pleased with what he saw and gave William instructions for more work to be done.

All this work was completed and in January 1890, builder William sent in his final bill … which John refused to pay !! By now (since October 10th, 1889) stationer Andreas Cokayne had become lessee of the shop, and according to John, under the terms of the lease Andreas was responsible for organising the repairs and paying for them. When the builder pointed out that it was John and his agent who had given him the repair instructions, John still refused to pay. William was encouraged to send his bill to Andreas — John was sure that he would pay !! As so often in the past, John was wrong !! Andreas would not pay, and directed William back to John !!! At which point John pleaded illness — now he had bronchitis — but he would soon be seeing his solicitor in Nottingham and then would get back to talk to William. But “get back to William” never happened.

Since then John had never paid for the work and no more was heard from him until William took the case to County Court nearly five years later !! At that Court John denied almost all of William’s arguments and testimony — he did not give instructions for any repairs, did not ask Thomas to act for him, and did not visit Ilkeston to view the work being done. The judge was not impressed by John’s defence and without hesitation ordered the bill to be paid in full, with costs.

Andreas Cokayne had left the shop on March 25th, 1890.

John Wombell died at Carlton House, Ashover, on June 5th 1896. His body was returned to Ilkeston to be buried at St. Mary’s Church.

And once more John’s premises — shop and cottage — were advertised as up for auction (presumably not having been sold previously ?)

Susanna and Emma Wombell continued to live together in Ashover as spinsters, and died in 1922 and 1930 respectively.

Maria Beardsley and her son George Wake Beardsley.

Maria Beardsley, the daughter of stone miner Mark and Sarah (nee Trueman), had been born in Ilkeston in May 1831 and in October 1832 was baptised into the Primitive Methodist Church. In October 1853 she gave birth to her illegitimate son, George Wake Beardsley, and then in September 1858 married stone-miner Lewis Russell, after which she continued to live in Granby Street with her parents, her husband, her illegitimate son and her later Russell children.

Maria died in January 1898, eight years after her husband.

On Christmas Day 1874 George Wake Beardsley married Mary Columbine, daughter of lace maker James and Sarah (nee Percival) and cousin of Elizabeth Adeline Columbine. At the marriage ceremony George gave his father’s name as ‘John Wombell’, printer.

His mother and step-father were witnesses at the event.

In the Derby Daily Telegraph, dated Monday, June 3rd, 1901 the following article appeared …

“Strange Affair at Mickleover Asylum ; Ilkeston Miner’s death.

“It has been reported to the county police that a patient at Mickleover Asylum has died under circumstances that are somewhat extraordinary.

“His name is George Beardsley, aged 47, who lately resided in Slade-street, Ilkeston, and he was admitted into the institution as recently as May 27. He died on Saturday, June 1, or five days after his admission, from ‘general paralysis, accelerated by broken ribs’. The report of the Asylum officials states that there is evidence of various external injuries, and ‘one or more ribs’ are broken.

“The Coroner (Mr. W. Harvey Whiston) ordered a post-mortem examination, and has fixed the inquest for four o’clock this (Monday) afternoon”.

And the following day the same newspaper reported upon that inquest.

Evidence was given by George’s son John, aged 17, who lived with his parents at 1 Slade Street.

George, a collier, had not worked for about eight years because of illness — asthma and bronchitis. Latterly his mental condition had deteriorated such that he had threatened to chop his wife up with a spade. He was restrained but that evening went out into the street, shouting loudly. His behaviour continued to be very erratic and worrying, and at one point he was restrained by the police. Eventually the relieving officer took him to the asylum. John did not know what had triggered his father’s ‘attack’; he had never before showed signs of lunacy and had not been drinking.

The medical officer at the asylum then gave evidence.

George was admitted as a suicidal patient. He was examined a few days after his admission and found to have some cuts, bruises and scratches about his body. A broken rib was also discovered and this was treated up until, two days later, George died — the cause being ‘general paralysis, probably accelerated by the injury to his ribs‘.

A post-mortem examination had been performed and had revealed a total of 13 broken ribs; the ribs were so weak that they could be broken between the finger and thumb; there was no external bruising, suggesting that the injuries might have been caused by pressure, by the patient being restrained; the ribs were then pressing on the lungs. This examination supported the view that death was caused by ‘general paralysis, accelerated by the fracture of the ribs, and injury to the lungs’.

All evidence therefore pointed to George having received the injury to his ribs after his admission to the asylum.

Several attendants at the asylum gave evidence that George was extremely restless while he was at the institution, had to be calmed on several occasions and had to be often returned to his bed during the night-time. No excessive force was ever used and George had not complained of any pain in his body.

After a short deliberation, the inquest jury concluded that the cause of death was, indeed, general paralysis of the insane, accelerated by the broken ribs and injuries to the lungs .. no external force was responsible for the fractures, which were most probably caused by George, straining against the straps across the bed as he tried to get out one evening.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Doxey School

*In her letter on Ilkeston’s schooling Adeline mentions the Doxey school; “A school was started I think about 1859 or 1860 at the top of Bath Street on the left hand side going to the church in a house now converted or turned into a public house. It had a shop front in those days and a building at the side in the yard.

“The three ladies of this establishment were the Misses Harriett, Minnie and Lizzie Doxey. They afterwards went into one of the two new houses built by Joseph Carrier, grocer and draper.

“After a time here they went to Albion House against Ball’s factory”. (See Dame Schools)

Elizabeth (born 1835), Harriet (1837) and Miriam (1841) were the youngest children of coal agent Thomas Doxey and his wife Elizabeth (nee Gaskill), all born in Nottinghamshire before the family came to Ilkeston in the 1850’s.

Older sister Mary Ann Gaskill Doxey was a milliner and, for a time, from the summer of 1858, kept a shop with her sister Elizabeth. It was opposite New Street, later called Station Road.

In 1864 Mary Ann married pork butcher George Bunting who traded just up the road at the corner of East Street.

Elizabeth married John Boustead on September 14th 1869.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

In John’s obituary, dated June 12th 1896 and appearing in the Ilkeston Pioneer, it is pointed out that he was connected with the Primitive Methodist chapel but afterwards became ‘a Churchman‘, regularly attending St, Mary’s Church. We already have a pretty good idea why this ‘conversion’ took place, We can investigate the incident in a little more detail in the next section.