After the York household, Adeline recalls that “next was Robey’s Yard, with one or two cottages (now a funny-looking yard)”

We are standing in South Street, looking at the entrance to Robey’s Yard on the left of the picture. (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library). The two thatched cottages were demolished in April 1914.

Robey’s – or Robey — Yard was previously known as Skevington’s – or Skeavington’s — Yard, where Christopher Harrison, hosier of Moors Bridge Lane, once had his workshop. He was married to Nanny Skevington, daughter of carpenter Henry and Catherine (nee Matthews) and the aunt of the fowl filchers and milk rustlers Henry and Solomon Skevington.

The Robeys of Robey Yard

Father John Robey junior

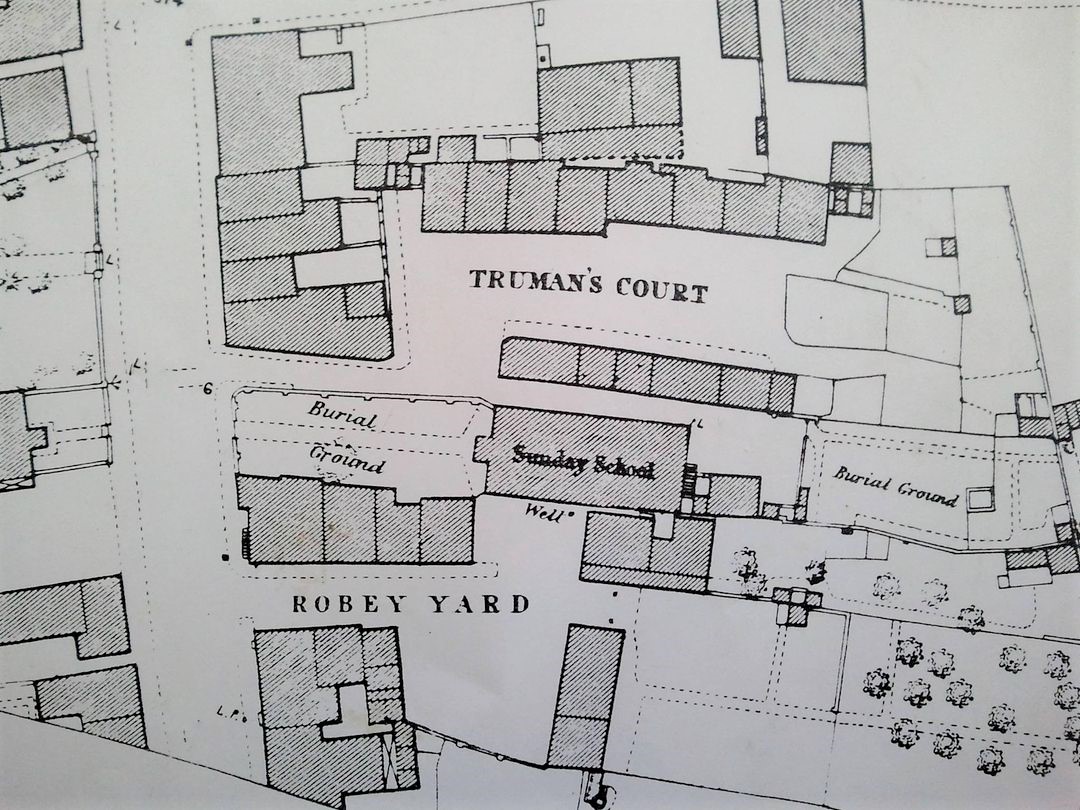

Adeline remembers the yard : “Robey’s greengrocer’s shop was in front with a long flight of stairs over the shop door leading to a dwelling that went over the lower houses. Mrs. Robey was an invalid, a very delicate person.” (Can you spot the flight of stairs in the map above ?)

Born in Melbourne, Derbyshire in 1824, greengrocer and fruit dealer John Robey junior was the son of gardener John and Mary (nee Dunnicliff).

The family moved to the Nottingham area and by the late 1830’s were living in Basford.

John junior married Ilkeston-born Hannah Bower, eldest child of Little Hallam cattle dealer and farmer Gervis (Jarvis or Gervase) and Sarah (nee Bower) at Nottingham in November 1844.

And by 1850 the couple were living in Ilkeston when their son John Bower Robey was born.

In May 1874 John had gone to the Saturday market in the Market Place, expecting to set up his stall at his usual pitch, when he discovered that elderly Letitia Betts and her husband, selling their new potatoes, had got there before him. John was outraged and shouted instructions to his son —

“Run over the b*******” (substitute ‘boggers’?).

Thereupon their goods were overturned and ruined, Letitia was struck twice in the face by John causing her nose to bleed, and her bonnet and black dress were damaged in the fracas.

At least that was the story told by one party to the argument. John’s account was slightly different.

Yes, he had been put out by the usurpation of his pitch and had tried to move the Betts couple along. They had retaliated by insulting his produce calling it ‘rubbish’ and calling him a thief. The husband had threatened him with a 4lb weight while Letitia had got hold of his coat and tried to throttle him. He had not struck her – her nose-bleed was caused accidentally by her own husband – John had simply pushed her away.

To the magistrates at the Petty Sessions, even that last act amounted to assault and the greengrocer was fined 5s and costs.

He paid up immediately.

In July 1880 John took a late Friday night ride in his pony and cart down to the Bull’s Head Inn in Little Hallam and there got into an argument with young brothers James and William Parks, who lived at Hallam Fields and worked at Stanton Iron Works. The two left the pub but when John followed shortly after he discovered that they had driven off in his cart!

The police were alerted and soon discovered the hijacked cart down the Nottingham Road, stationary and with a broken harness.

About midnight and further along the same road, at Trowell, one of the brothers was overtaken riding John’s exhausted and beaten pony. The other brother was nowhere to be seen, and nor were a long chain and horse rug, property of John and previously in the cart.

Charged with stealing the horse and cart, both brothers later found themselves in the lock-up, where their defence was:

a) that they were drunk and so not really sure of what they were doing,

and b) that it was all John’s fault anyway because his argumentative nature had provoked them in the first place!

When their case reached Heanor Petty Sessions a couple of weeks later the case was dismissed, through insufficiency of evidence.

John’s first wife Hannah died at their Robey Yard home in March 1881, aged 52.

Having moved from Robey’s Yard into Nottingham Road (number 20), John Robey went missing on Saturday morning, January 6th 1883, and was found two days later in the Erewash Canal at Gallows Inn.

He had been married to his second wife for just over a year.

She was born Frances Lowe in Cossall, daughter of labourer Richard and Sarah (nee Wheatley) and was the widow of John Hargreaves of Park Road.

The couple had gone to bed between 9 and 10 on Friday evening when a less than cheerful John was in poor health, having a very bad cough. He was in low spirits and had been so for about two weeks.

‘Trouble is coming’ he murmured prophetically before retiring to bed. Frances thought he might be referring to the debts he owed and the pressure he felt from this. She had had to give him money — £15 in all — which she had earned from her charring.

In the night John complained of back aches and rose about 5am, — earlier than usual — went downstairs, taking the candle with him and shortly thereafter the house door was noisily shut. Fanny called to her husband — ‘Robey? Robey?’ — but there was no answer. She went downstairs to find the candle put out, the door closed but unlocked, and John gone. His purse and 7s 9d lay on the kitchen table.

Son John Bower Robey was eventually alerted when his father had failed to meet his granddaughter as he had earlier arranged.

When there was no sign of his father by Saturday night son John became more uneasy, … and became even more uneasy when his father’s hat was found in the canal the following day. On Sunday night part of the canal was drained and about one o’clock on the Monday morning John’s body was discovered.

At the inquest into John’s death at the Horse and Groom Inn on Tuesday evening, Fanny voiced her disquiet about her husband’s mental state and this was confirmed by Edwin Trueman. The latter had spoken with John a couple of days before his disappearance and found him worried about his debts and an imminent appearance at court; he was in a low state, taciturn and not his usual jovial self.

John junior’s death was considered as a ‘possible suicide’ but as there was a lack of direct evidence to support this, the inquest jury returned a verdict of ‘Found drowned’.

He was aged 58.

…. and son John Bower Robey

“Their only son, John, helped his father. He married a Miss Fraser.”

The only child of John and Hannah was John Bower Robey, born in Ilkeston in August 1850. In July 1873 he married Caroline Frazer, the daughter of Bedford clothier William and Jane (nee Lincoln?).

John Bower died in July 1889, while then living in Nottingham Road, and in 1892 Caroline remarried to Edwin Ball (his third wife), lace factory foreman, son of South Street lacemaker Thomas and Frances (nee West) and brother of the Ball’s Yard Balls.

PS … John Bower Robey’s first cousin once removed was Jane Carline Bower who died and was buried several thousand miles from these burial grounds.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

A troublesome place

1890: The Yard’s ‘No Entry’ sign gone for good !!

By 1890 it seems that the police were fed up with riotous behaviour in and around Robey Yard, which many of its residents claimed as a ‘private place’ where the police were not allowed entry and had no right to interfere. However — and correctly — to the police, it was a ‘public place’ and they had every right to attend disturbances there. Like the ‘drunk and disorderly’ brawl in September, involving Thomas Sudbury and William Robinson alias “Slap”. The latter made a pathetic plea at the Petty Sessions for mercy, explaining that he had ‘his old woman’ to care for; his missus was dying and he sat by her bed on ‘nightly vigils’ which were driving him ‘luny’ — he just couldn’t afford any more expense. Through tears, he described how he had been to view her burial plot the day before, and if they sent him to prison he would come out ‘to an empty home‘. The Police Superintendent didn’t particularly want to pursue the case, but wanted it clearly established that the Law had every right to interfere with rows in the Yard. The magistrates said that they had nothing to do with ‘the old woman‘, and the pair were fined. The magistrates also made it very clear that the authorities had every right to enter the Yard when they wished.

Further turmoil

And so the police continued to enter the Yard, often to deal with Thomas Sudbury, his family members and his ‘mates’. As in mid-November 1892.

Thus, on November 17th, several inhabitants of the Yard appeared at Ilkeston Petty Sessions. William Sudbury, son of Thomas, was in court, accused of assaulting his neighbour Mary Ann Jane O’Connell, who kept a lodging house there, on two separate occasions. Mary Ann Jane appeared sporting a shiny black eye; she too was accused of assault by Hannah Bostock, who sported a similar black eye. Thomas Sudbury’s wife Mary (nee Gaffney) wasn’t left out; she was there both as a witness for Hannah and as a victim, who claimed that Mary Ann Jane had assaulted her too.

After much fruity language in court, meandering testimony and audience laughter, some fines were imposed, several of the charges were dismissed, and Mary Ann Jane O’Connell was carted off to prison for a couple of weeks, having refused to pay her fine.

Just to clarify at this point, Thomas Sudbury (1846-1905) was the son of William and Lydia (nee Brown) of 2 High Street and had been christened ‘John Thomas’, though as the years passed, everyone (mostly magistrates and the police) knew him as ‘Thomas’. He had married Mary Gaffney in 1877 and by so doing, he had ‘inherited’ her three illegitimate sons, John, William and Thomas. These lads might have been his sons and took the name of Sudbury at various and intermittent times in their lives.

And the police continued to enter the Yard just as its residents continued to argue amongst themselves.

May 26th, 1895, at 1.45 am was a quiet, sleepy Sunday morning — at least in most parts of Ilkeston. However in Robey Yard Mary Sudbury and her son William Gaffney alias Sudbury were at it again. Police Inspector Savory had arrived there, alerted by the foul language being used by Mary. Her husband, John Thomas, came out to shepherd her back into their house when drunken son William struck him. The Inspector tried to calm things down, but was struck by William and then attacked by his mother and his brother John. A melee ensued. All were later charged with either being drunk and disorderly, or with resisting and obstructing the police. William and John were, once more, carted off to jail, while the case against mother Mary was withdrawn on the suggestion of the Bench.

William and John Gaffney alias Sudbury had a younger brother Thomas (also alias Gaffney) who wasn’t involved in this fracas. He was probably in bed at the time, feeling very poorly — and was just about to be admitted to the Ilkeston sanatorium, suffering from smallpox. He had to wait however, as a young lass with scarlet fever had to be moved out to provide a place for Thomas. The latter had recently slept in a lodging house in Walker Street, Derby and this is where he probably contracted his disease — that district of the city was suffering from an outbreak of smallpox at that time.

A further brief description of the quarrelling inmates

Mary Gaffney was born in Sligo, County Sligo, Ireland, about 1849 and she first appears at Ilkeston, on the 1861 Census, close to the Three Horse Shoes Inn on Moor’s Bridge Lane. She is with her parents Edward and Margaret.

Living first at Fletcher’s Place in Bath Street, and then in the Trueman’s Court/Robey Yard area of South Street, she had her three illegitimate sons — John (born July 18th, 1872), William (March 14th, 1874) and Thomas (March 14th, 1876). In 1877 she married lacemaker (John) Thomas Sudbury of High Street and her sons then adopted the surname of Sudbury. Mary and John Thomas then had at least nine children at Robey Yard.

The family moved to Tutin Street, off the bottom of Bath Street, in the late 1890s. (John) Thomas died there, at number 7, in 1905; Mary died at the same home on July 12th 1914, aged 65.

The Shaw legacy at Robey’s Yard

When we encountered butcher Joseph Shaw, on the other side of South Street, it was mentioned that his father John held some property in Robey Yard.

John died in 1823 and the copyright property passed to his widow Mary (nee Wheatcroft).

She died in 1861 but not before she had made her own will (dated November 29th, 1860) in which she set out a precise path of her legacy.

She left the property in trust to her daughter Mary Shaw (born in 1814) who had married wheelwright William Severn on October 7th, 1834.

When Mary Severn died in 1874 the property then passed to her husband, who died in 1885.

The property was then to be shared among the six children of William and Mary Severn. In the will certain trustees had been named but by the death of William Severn these trustees had all died. As a result new trustees should have been appointed but they were not; instead the names of the children were incorrectly inserted into the copyhold roll.

By April 1897 four of the six ‘children’ were left to sort out the legacy and so they took the case to Ilkeston County Court.

These four children were Millicent Garlick (nee Severn, and now the wife of Joseph Garlick); Mary Mellors (nee Severn) who had married Thomas Mellors in 1855; Martha Clifford (nee Severn), the wife of miner Robert Clifford; and Louviena or Lovina Severn (nee Beardshaw), the widow of William Severn who was the deceased brother of the other three. To make the issue more complicated they were faced in court and challenged by William Howson, the widower of another Severn sibling, Phoebe; he was joined in the court case by his son, William Charles Howson, and by William Albert Severn, the son of William and Lovina.

What all parties wanted was for the judge in the case to appoint a person to sell the property. They were all agreed that the Robey Yard property should be sold, the proceeds then paid into the court, and finally divided up according to their interests. Eventually, to oversee the sale, the judge appointed Samuel Broadhurst, who was a grandson of one of the four children, Martha Severn (now married to Robert Clifford remember !!).

Post script — a Mellors mix-up

Thomas Mellors (husband of Mary (nee Severn)) died in May 1897 when at Mickleover Asylum. He was aged 65. His relatives contacted Ilkeston undertaker David Johnson of 80 Bath Street, to transport his body from the asylum to Stanley village (in Derbyshire) where it was to be buried at St. Andrew’s Parish Church.

David had known Thomas in the past, when the latter was living in Ilkeston, and when he saw the body at Mickleover he instantly recognised that this was not ‘his’ Thomas. In particular, Thomas was known to have a distinct peculiarity — having two thumbs on one of his hands. The undertaker was convinced that a mistake had been made, and indeed it had !! Another man’s death had occurred at the asylum the same time, and his body was the one which now confronted David. Thomas’s body was already on its way for burial at Glossop, the home of the second man. A telegraphic message was immediately despatched to halt the interment, and send the body back.

After a short delay, the problem was resolved and the two bodies both found their correct final resting places. Thomas was buried at Stanley on May 15th, 1897.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

We can rest here to peer into the burial grounds of the old Baptist Chapel and to consider the Baptist Chapels of Ilkeston in general.