Samuel Shaw’s Estate: 1881-1905

(Details and plans courtesy of Jim Beardsley’s archive)

Coming back from Grove Terrace and retracing our steps up the south side of Station Road, Adeline introduces us to Samuel Shaw, living up “a narrow side road. Here in later years Mr.(Samuel) Shaw built a small house, in which he and his family lived. I remember two of his daughters, Frances and Janey.

“Continuing through this road we come to another lane, which is now Lower Chapel Street. Here was some old property, with backs up to the road.”

From her description, the ‘narrow side road’ mentioned by Adeline must have led from Station Road and into Lower Chapel Street; it may be the southern part of North Street between Station Road and Chapel Street before it joined with Burr Lane … that appears to be the only named side road in the area at that time. That is where the Shaw family had its home on the 1881 census.

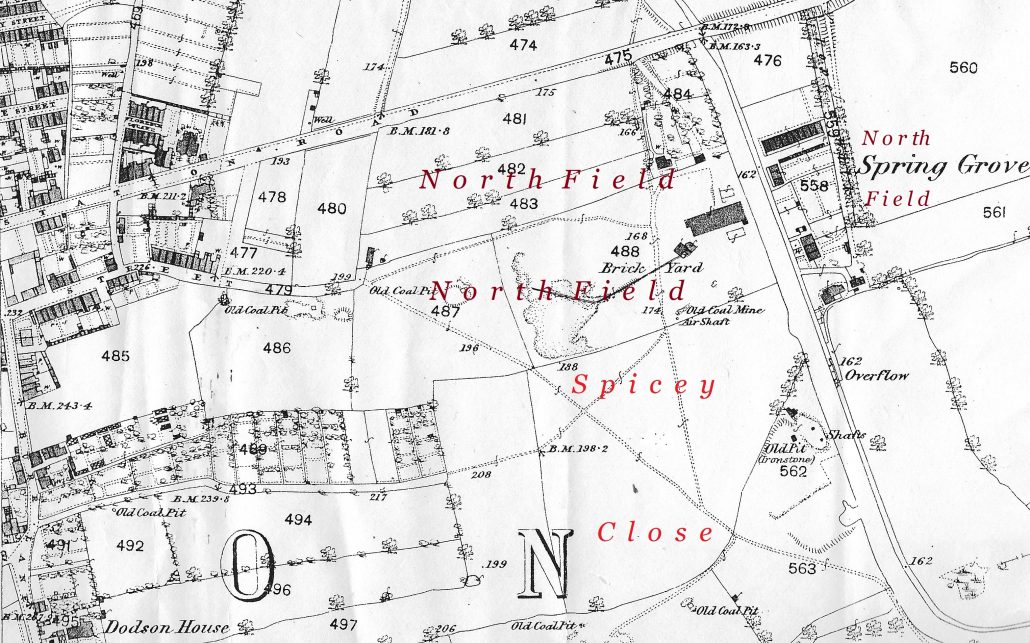

It was once part of the estate of George Blake Norman and the Shaw home comprised a cottage, orchard and two closes of land called the North Field (in the prvious century owned by Michael Skevington) — which housed a brickyard in 1881– and the Spicey Close (called Spicer Close by some sources). It was just over 12 acres in area.

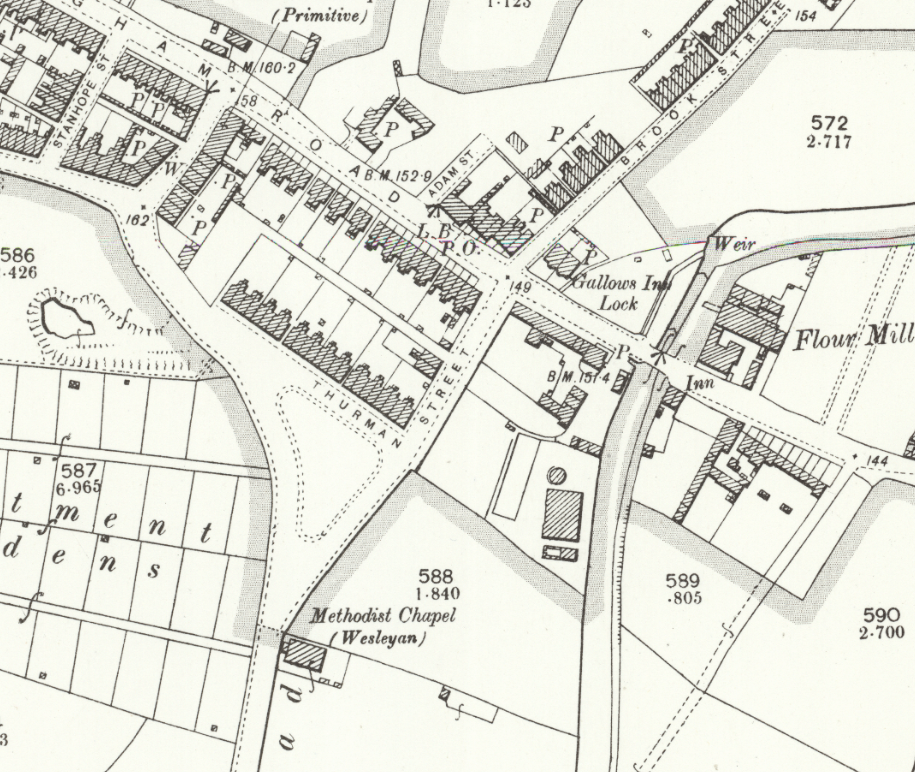

In November 1885 Samuel Shaw took out two mortgages, totalling £2200, with Thomas Arthur Hill, a hosiery manufacturer of Standard Hill in Nottingham. The property he mortgaged included 5½ acres of land in the area called ‘North Field‘, and lay at the end of what is today Lower Chapel Street. A small portion of North Field could be found on the west side of the Erewash Canal — the rest lay on the east side, as you can see in the map below. This is adapted from the 1881 O.S. map.

You can see Station Road, from left to right, with no named streets leading off from either side. Lower Chapel Street is marked by number 479 and ends abruptly at North Field.

On Samuel’s land there were “five messuages or dwellinghouses, stables, storerooms and other buildings” as well as a “brickyard with buildings erected”

Between 1886 and 1904 changes were made in the mortgagees of this property, while, during that time, the brickmaker erected four additional houses, fronting on to ‘(Lower) Chapel Street‘, enfranchised other parts of the land, and sold off some portions. And at the end of 1888 he was in trouble with Ilkeston Town Council for starting to build two houses on this land — on Taylor Street to be precise — without submitting plans to the council or getting permission to build. He was told to stop while plans could be drawn up. In the meantime he appeared at Petty Sessions for his indiscretion and fined 10s with 9s 6d costs.

By 1901, Samuel’s piece of land now measured a little under four acres, upon which eight houses had been erected on Chapel Street East (Lower Chapel Street). These were recorded as numbers 56, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 75 (should be 76?) and 77, and on the census of that year, the first was uninhabited while the rest, respectively, were occupied by the families of brickmaker Joseph William Shaw (son of Samuel); coal miner Adrian Smith; retired brickmaker Samuel Shaw senior; colliery carpenter William Massey; stone mason George Orchard; coal miner William Dilks; and widow Annie Key (though this house may have very recently housed the family of the late Joseph Spowage).

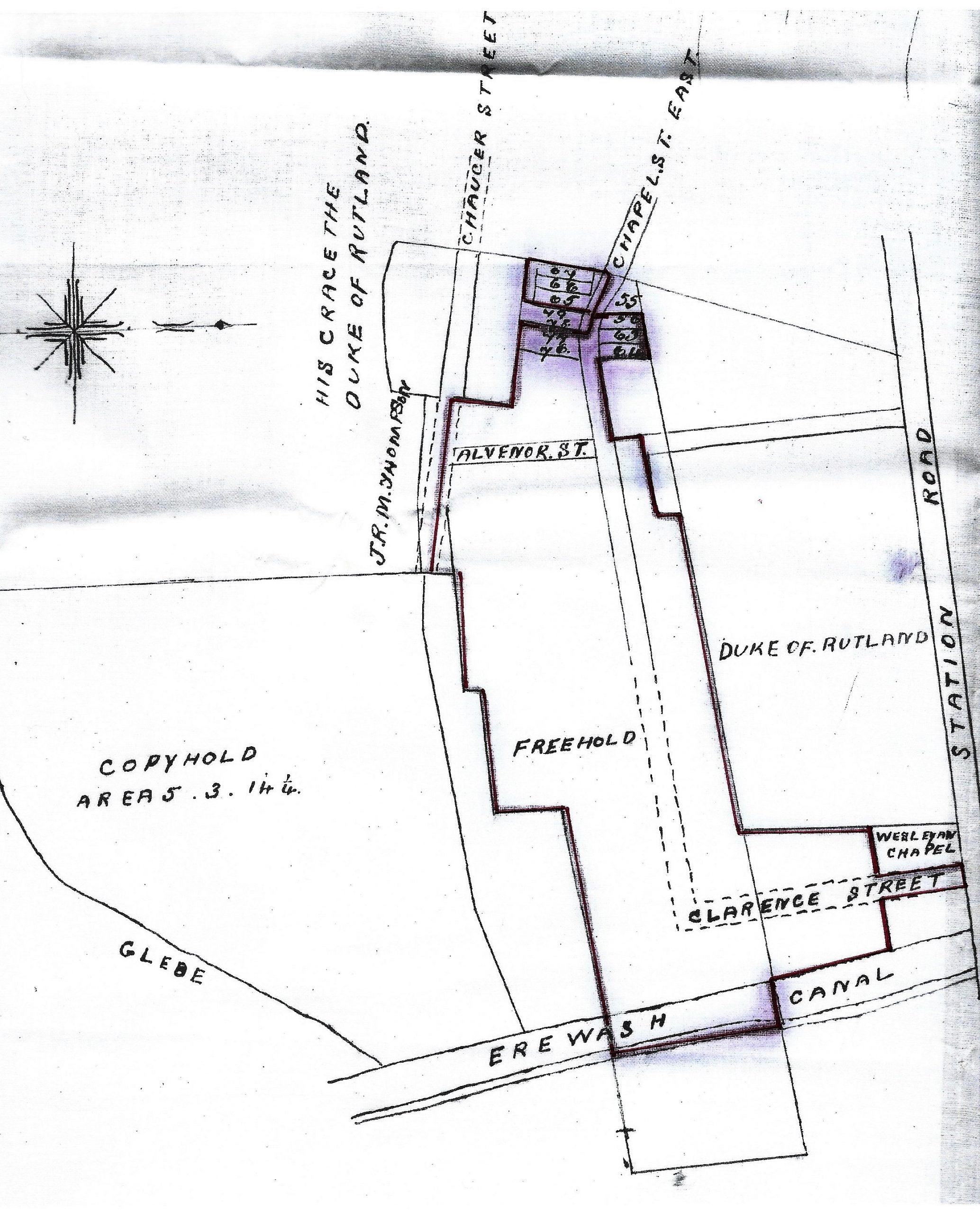

Plan 1: taken from a property document, 1905

On Plan 1, the late Samuel Shaw’s estate is within the boundary marked with a red line. The eight houses, erected in Lower Chapel Street, are numbered, along with a few neighbouring ones. Present-day Rupert Street is marked as Clarence Street – why ? — it could be that Gordon Street and Clarence Street were both named after Samuel’s grandson, Clarence Gordon Shaw, born in 1892, (son of Samuel Shaw junior). You could see John Beniston’s comment on the naming of Alvenor Street

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

On January 3rd 1904 Samuel Shaw died at his Lower Chapel Street home, aged 73. In his will he had appointed, as executors and trustees, his two sons, Isaac and Joseph William, and his son-in-law Thomas Beniston (who had married daughter Jane Maria Shaw in 1876). The will had been made in 1895, in the year before Jane Maria died. And so, by the time Samuel Shaw died, was he still the father-in-law of Thomas ? — especially as Thomas had remarried in 1899 ?

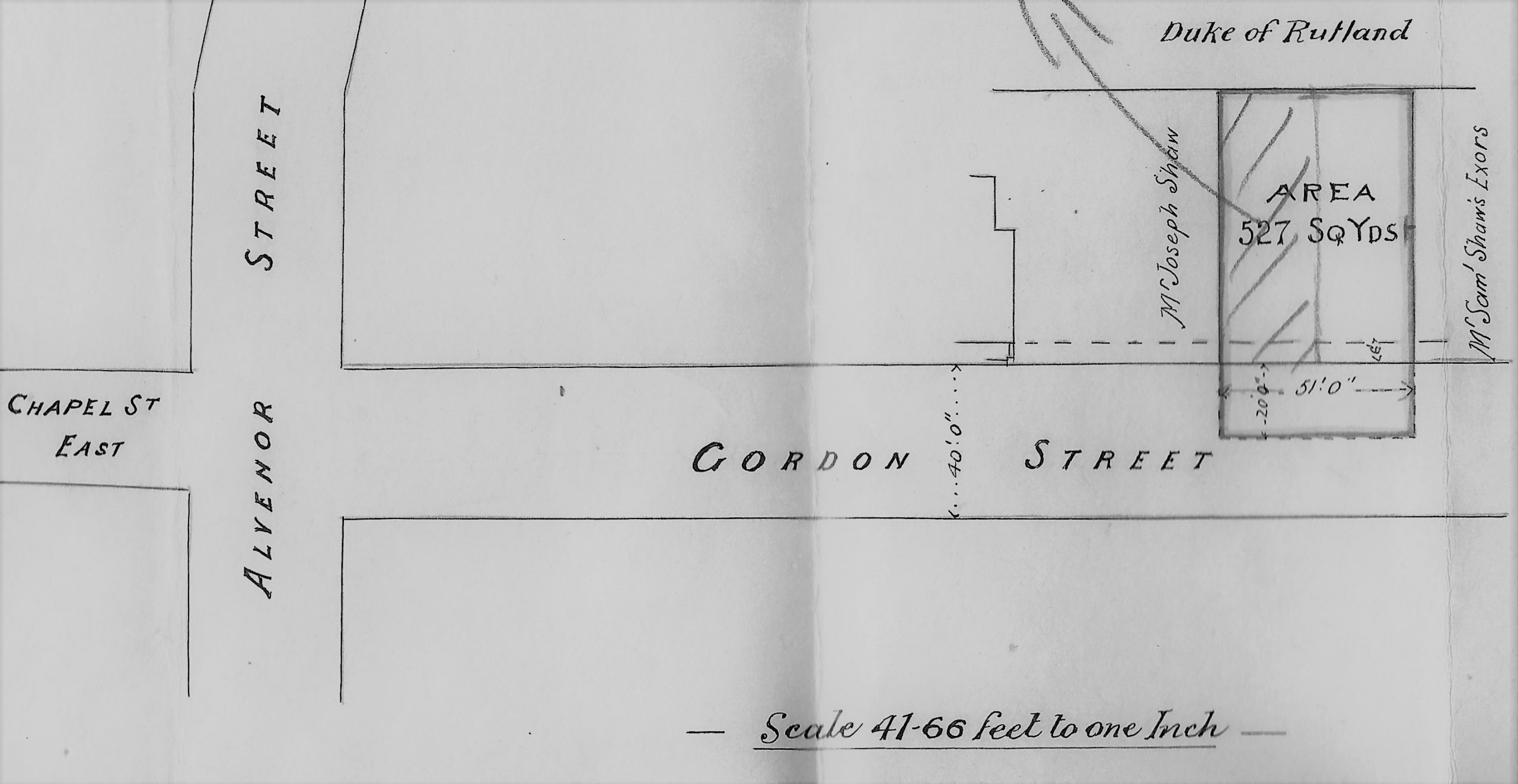

At the end of that year, the three executors agreed to sell to Samuel Shaw junior (the eldest son of the late Samuel) a piece of the estate, situated in Gordon Street and measuring 527 square yards — the purchase price of which was £52 7s. At this time hosiery manager Thomas Beniston was living in Sao Paulo in the Republic of Brazil and so it’s unclear how much he knew of this sale. The premises on the north side of the land were owned by the Duke of Rutland; on the west were the premises of John William Shaw; on the east was property of the estate of the late Samuel Shaw senior; and on the south was Gordon Street, which as yet had not been adopted by the Borough Council as a ‘Public Street‘. You can see these features in the plan below.

Plan 2: taken from a conveyance document, December 31st 1904

A month later — on January 30th 1905 — Samuel Shaw junior sold the same 527 square yards to his younger brother Joseph William, for £56, and six months later the latter arranged mortgages for the property. The mortgagees were John Ball J.P. of Dodson House, his nephew William, then a lace manufacturer living in Hyson Green, Nottingham, and his niece Elizabeth Susan. By this time four houses had been erected upon the Gordon Street plot (by builder Joseph William ?) — they were numbered 13, 14, 15 and 16.

Seven years later — in September 1912 — with none of the principal loan repaid and some interest payments outstanding, the three mortgagees foreclosed on the mortgage.

On April 21st 1926, the four houses were sold for £625 to warphand Walter Frederick Parsons of 40 Carr Street, Ilkeston.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Samuel Shaw (1830-January 3rd 1904) and his family

Samuel Shaw senior was born in Kimberley about 1830 the son of collier William and Alice (nee Revell) but lived the majority of his life in Ilkeston.

On August 7th 1854 he married Jane Smith, daughter of Joseph, lacemaker of Awsworth Road, and Maria (nee Cook) and did not wander far from this area for the rest of his life.

Samuel played a prominent part in the business, social and religious life of the town.

As a young man he began an association with the Primitive Methodist chapel, and for many years was a local preacher and trustee for both the Bath Street and Nottingham Road chapels, as well as providing service to the Sunday school.

The Ilkeston Advertiser of 1904 recalls that “in early life he was a contractor at the ironstone pits situated near the present Bennerley furnaces after which he worked his own land for getting coal”. Then for over 30 years he was a brick maker using the clay lying beneath his land.

In November 1893 a new coal source — the Piper seam — was opened in Samuel’s brickyard.

Samuel retired in 1893, leaving his oldest surviving son Samuel junior in charge of the business and leaving himself free to travel extensively. He visited the Channel Islands, the south of France, several health resorts but particularly enjoyed Wales. There he could pursue his fishing, the sport of which he was passionately fond.

In politics Samuel was ‘an independent Conservative’ and for some years was a member of the Local Board. However he had not held public office for many years before his death in January, 1904 in Lower Chapel Street.

By that time he had just seen son Samuel elected to the Town Council but did not see him made mayor in 1910.

The Shaw children

Samuel and Jane had at least ten children, the eldest two recalled by Adeline.

Daughter Jane Maria married Thomas Beniston, hosiery warehouse manager, in 1876 and in the following year her sister Frances Alice married William Holbrook, painter, plumber and paper hanger. The latter established his business initially in Station Road and then, about 1888, moved into Bath Street. And it was while there that William ran into a bit of bother with the local Town Council. In November 1891, he was doing building work in Stamford Street and connected his water pipe to service pipe belonging to the Corporation, so that he could mix his mortar there. And that was very naughty of him !!! He hadn’t obtained consent from the Council to do that, and so, at the Petty Sessions was fined 20s with 23s costs.

By the end of the century the Holbrook family was living in Nottingham.

But what of the others?

Isaac William, born in 1860 died in infancy, in 1861.

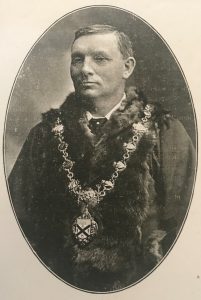

Born May 16th, 1862, Samuel junior (right), like his father, was a brick manufacturer, and in 1885 married Lydia Emma Evans of South Street, the daughter of sanitary inspector Thomas and Ann (nee Jones).

and also like his father, played a significant part in civic affairs.

In the early twentieth century he served on the Town Council and was elected Mayor in 1910 .. and thus he features in the town’s Coronation booklet of 1911 (supplied by Mike Hallam)

Joseph William (1864), like his brother, remained in Ilkeston, married Kate West in 1887, and traded as a bricklyer/builder.

Isaac (1866) trained as a colliery clerk, married Hannah Millicent Chapman of West Hallam, and continued to live in Ilkeston.

Agnes (1868) actually left Ilkeston after her marriage to John Edwin Walker, lace machine engineer of Kimberley in 1894. They departed for Nottingham

Frederick Charles (1870), another brickmaker, married Harriet Elizabeth White, in 1892. They too made Ilkeston their home.

Kezia (1873) .. ?

Jane died eight years before her husband and both are buried in the same grave at Park Cemetery.

A Shaw sibling

A younger sister of Samuel was Mary Ann, born about 1844, and who might have been an illegitimate child. Married in 1877, her second husband was Samuel Cunnington who was employed for a time by her brother Samuel while they were living in Taylor Street. He did very little work however, often saying that ‘Jesus would keep him‘; at times he would carry a stick with him, declaring that, as long as he had it, neither the police nor magistrates would touch him. His behaviour had previously led to a temporary spell in the ‘Asylum’ but now, in 1890, he was rather more crafty, and avoided company. However he was also abusive, towards his wife and daughter Charlotte, and on occasions had shut them both out of the family home.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Station Road Wesleyan Chapel

We are now at what locals call ‘the bottom of Station Road‘.

Here is a map of the area at the end of the Victorian years. You will notice a lack of streets around the Shaw Brickworks. If you locate the gap between the two buildings at “Mission Hall” off Station Road, that is where Alvenor Street was later built. It proceeded southwards (down), between the gap in the houses directly below, and on, past the end of Chaucer Street. It then joined on to Flamstead Road, also later built. You can also see the Methodist Chapel (Wesleyan), looking out onto Station Road with an unnamed Rupert Street to the east (right)

The Long Eaton Advertiser (July 15th 1893) described Ilkeston’s Wesleyan Methodists as “an aggressive folk, intent upon occupying a leading position among the various religious bodies of the town”. The Wesleyans were now at their ‘old’ chapel in Bath Street which had been built in 1873 … a newer chapel (the one with the spire which many people may be familiar with) had not yet been built in front of the old one. From their Bath Street base they had established missions in Station Road and Nottingham Road.

The mission initially occupied a single room in Critchley Street, and had been established by the Wesleyan Young Men’s Bible Class, but in January 1890, moved into a room in Station Road, close to the Erewash Canal — at a rent of 10s per week. At the end of 1891 the site for the future ‘new, handsome and commodious’ chapel (almost opposite the ‘Canal’ mission) was offered by Samuel Shaw and was purchased — 549 square yards at 4s per yard, to be paid over 12 months with no interest charged. This site can be seen on Plan 1 (above) at the corner of Station Road and Clarence Street (later Rupert Street).

By 1893 the mission had 39 members, a Sunday School with 22 teachers and 100 pupils, and a Gospel Temperance Band of 50 … obviously more room was needed.

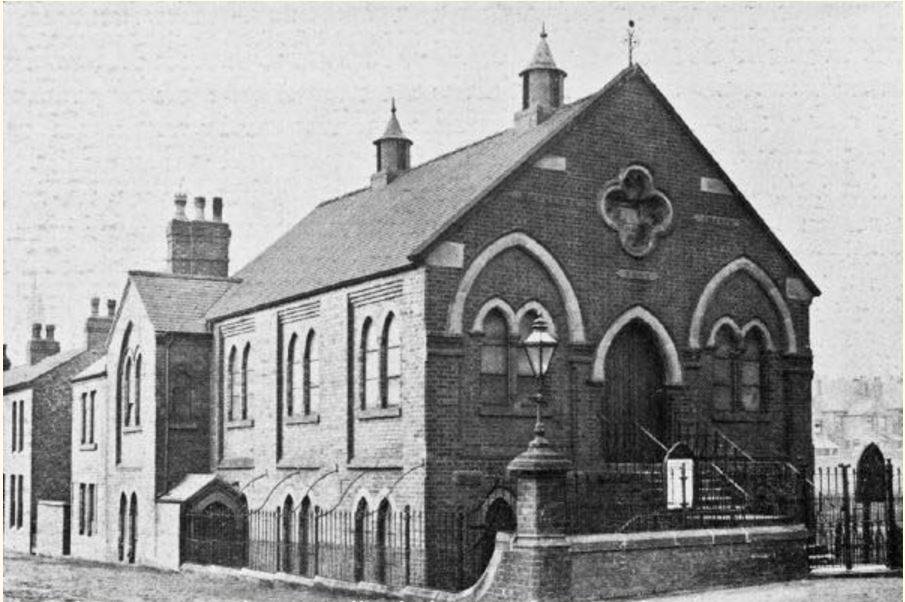

Station Road Wesleyan Chapel, built in 1893 (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library)

James Horsley Nicklin of Station Cottages in Brussels Terrace was the chosen architect (he was also a Wesleyan lay preacher); he had designed a building in Gothic style, with the front of red brick with Derbyshire stone dressings. There was to be a school on the ground floor, able to accommodate 200 scholars, with vestries at the rear. The chapel above, in cruciform shape, would accommodate 250 folk and would be reached by a flight of steps from Station Road. John Manners of 59 South Street was given the contract to build the chapel for £675; it was expected to be open for service in October.

The foundation stone of the chapel was laid on July 12th, 1893. The Rev. Thomas Roberts, superintendent of the Wesleyan circuit, officiated at the ceremony, while others taking part included Thomas Williamson of the Firs in West Hallam and George William Woolliscroft. In a recess in one of the stones were placed copies of the Methodist Recorder, the Methodist Times, the Joyful News, a copy of the circuit plan, and a short history of the mission, inscribed on parchment.

Someone from the watching crowd cried “What, another chapel !! Are there not enough in Ilkeston ?” The Wesleyans obviously thought not — there were already plans for another chapel in Nottingham Road and the splendid central ‘cathedral‘ in Bath Street.

On November 13th, 1893 the Mission was formally opened by the Rev. William D. Walters of the London Mission. But by the Spring of 1895 there was still an outstanding debt on the Building Fund of £600 (out of a starting total of £900) and the school under the chapel room was still unfinished and couldn’t be used; more building work wasn’t justified until that debt had been reduced … time for another bazaar therefore ??

In the following year the Station Road Wesleyan Band of Hope, attached to the chapel, was formed, and within a year had 150 members.

By 1899 the debt hanging around the neck of the chapel was £485 which needed to be reduced so that the completion of a schoolroom could be proceeded with … so, time for another bazaar, including a waxworks exhibition, musical selections, lectures on the X-rays and on phrenology. By the end of the year that debt was down to £360 (or £300 if the two Connexion grants could be secured).

And what about the other end of town ?

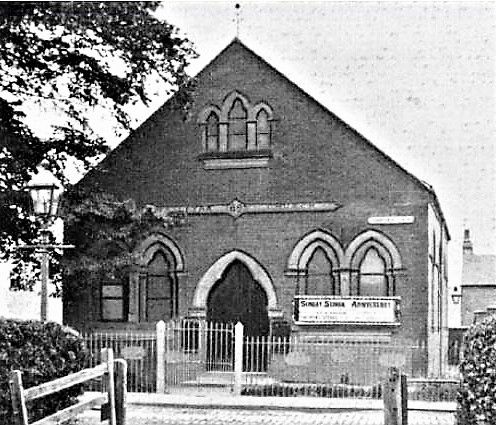

Almost two years after the Station Road chapel was built — on June 19th 1895 — the foundation stone of another Wesleyan chapel was laid, this one on Corporation Road. For ten years the congregation here had worshipped in an old foundry in the area, but now they were to be provided with brand new premises, some of the first bricks being laid by a number of scholars. It had also been designed by James Horsley Nicklin, in an ornamental Gothic style (as above), of red brick with stone dressing, to accommodate 200 persons. And once more, John Manners of South Street was the chosen builder. The cost was estimated at £600, of which £450 had already been raised or promised. It was to be ready for September … and it was !!!

Corporation Road Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, built in 1895 .. as the sign above the door reveals (from’History of Wesleyan Methodism in the Ilkeston Circuit (1909) by William Smith).

This new chapel actually cost £644 and, as was customary with such buildings, there was a debt to settle. The congregation was hoping that by the end of the year three-quarters of that debt would be paid off. By December of 1895 £430 had been raised and so a bazaar was arranged at which the rest might be secured. Stalls of crockery, food, general fare, a bran tub and fishing in the pond were all on offer. By March 1899 the debt was still £200 … and so it was ‘bazaar time’ again !! If the chapel could reduce that debt then it would qualify for a Connexional grant of £40.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

I want to pause here, and reflect on the Haywood and Richards families, who lived in this area.