After the Clarkson, Tooth and Pickburn’s premises, according to Adeline we then see “gardens, facing Club Row, a few cottages on the bank, (Field)

Next were steps leading up to Club Row Gardens and field. (The high bank with garden on it)”.

As today, there was a narrow alley leading from Bath Street up to the north end of Club Row.

On the map above you can just see Bath Street running down the centre with the British School at the bottom — on the west side of Bath Street.

The last houses of Club Row can be seen and there is the narrow alley leading from Bath Street to these houses’

————————————————————————————————————————————————

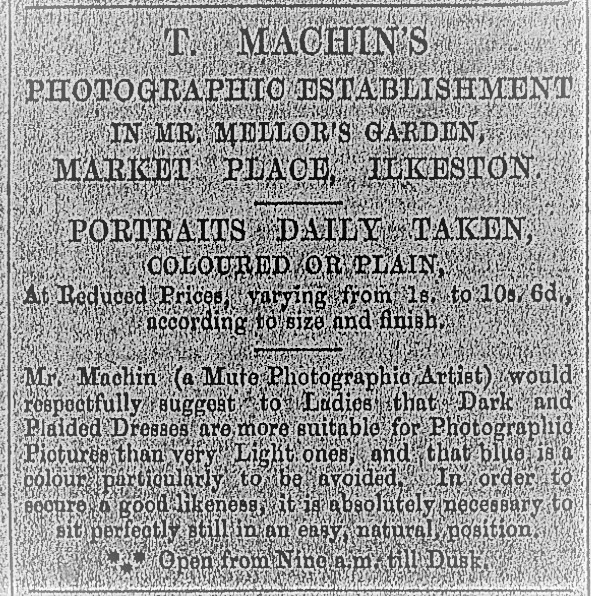

Thomas Machin.

“Next was a double-fronted house, standing back on the bank, with railings in front, and approached by several steps. This was occupied by a deaf and dumb photographer, Mr. Machin”. (Is this the double-fronted house on the map above, just below Fletcher Place ?)

Deaf from birth, artist and photographer Thomas Machin was born in Burslem, Staffordshire about 1808 and seems to have spent only a short time in Ilkeston in the late 1850’s before moving on to trade in Belper.

In 1858, his photographic establishment was in Mr. Mellor’s Garden in the Market Place … which was where Wharncliffe Road now is.

Thomas described himself as ‘a mute photographic artist’ who respectfully suggested to ladies that ‘dark and plaided dresses are more suitable for photographic pictures than light ones, and that blue is a colour particularly to be avoided’.To achieve a good likeness it was most important to sit perfectly still, in a natural, easy position.

He died in Belper in 1891, aged 83.

My thanks to Jon Baldwin whose research on Thomas Machin has discovered this obituary from the Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald (May 23rd 1891)

“Thomas Machin took two daguerreotypes of my parents, and they are as fresh today, as when taken in August, 1858.”

And recalling photographs of Adeline’s parents, I remember that a few years ago — when collecting material for this site — the curator of Erewash Museum allowed me access to their archives.

Lying on a stool in an upstairs room was a group of catalogued items waiting for filing, amongst them a photograph of an upright man standing beside a seated woman, both advanced in years.

The inscription on the reverse of the photo revealed that they were Adeline’s parents, “married at St. Peter’s Church, Mansfield, February 20th 1849, now residing at 6 Albert St., dated February 20th 1899”.

A Golden Wedding present?

Despite several returns to the archives and subsequent searches I never rediscovered the photo nor the name of the person who had donated it to the museum.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

Mount Row and its inhabitants

“Then came a narrow road leading up to two or three old cottages”.

These cottages were possibly those which formed Mount Row — not to be confused with Mount Street — situated a short distance north-west of the north end of Club Row, separated from the latter by open land and approached from Bath Street via a narrow alleyway.

On the map above, Mount Row is named and you can see the ‘narrow road’ from Bath Street to this row.

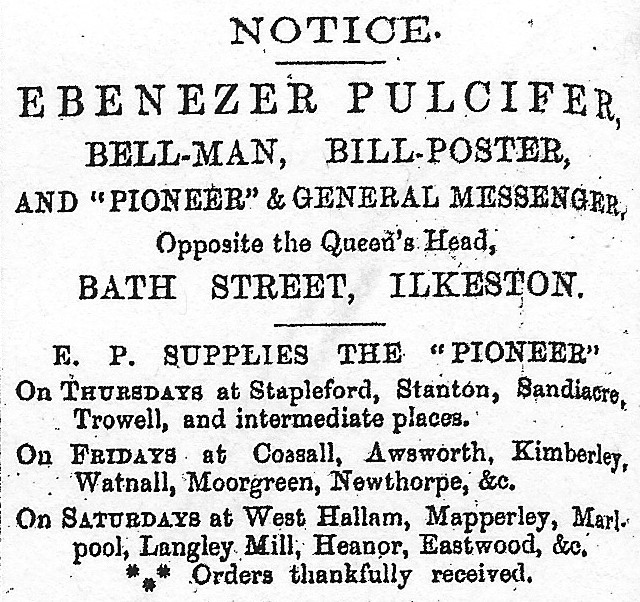

“In one of them lived Ebenezer Pulcifer senior, bell-man and bill-poster”.

Macclesfield-born Ebenezer Pulcifer married Esther Cadman, daughter of William and Elizabeth (nee Sharman?) in 1844. There is evidence that the family lived in the Manchester area and then in Hull before moving to Nottingham in the 1860’s where Ebenezer traded as a hatter.

Wright’s Nottingham Directory of 1862 lists him as ‘bill poster and bellman’ of the Plough and Harrow Yard, Milton Street.

Ebenezer died there in 1865.

It was probably in the later 1850’s that the family lived in Ilkeston.

For evidence, Ebenezer was advertising in the Pioneer, July 1st,1858, as ‘Bell-Man, Bill Poster and ‘Pioneer’ and General Messenger, opposite the Queen’s Head, Bath Street’. (Advert right)

And Ebenezer Pulcifer junior.

By the late 1860’s son Ebenezer junior was trading as a watch and clock manufacturer at 7 Sneinton Street and 57 Long Row in Nottingham, while also keeping a stall in the Market Place and at times visiting Ilkeston with his van, to auction his wares on its Market Place. And watches were not the only ‘wares’ that he sold!!

In June and July 1879 he was in Newark, Nottinghamshire, delivering lectures in favour of Republicanism, and found himself in front of the magistrates there after a series of disorderly melees during which Ebenzer pointed a loaded pistol. He was subsequently found guilty of inciting people to commit a breach of the peace and to damage property. For this he was bound over to keep the said peace for the next six months. But more was to follow!!

He was then charged with carrying a firearm without a licence; Ebenezer’s defence for this was that, as a hawker and gunsmith, he sold revolvers and so did not need such a licence. This time the magistrates were lenient with a light fine.

These events were referred to by some as ‘the Pulcifer Riots’!!

Six months later and ‘junior’ was in Market Harborough, Leicestershire, where more criminal ‘offences’ followed Ebenezer’s attempts to sell his goods in the highway. His actions and his language provoked the wrath of several residents, eggs were distributed and thrown, a revolver was brandished, and much of the local court’s time was spent in dealing with several cases following from these events. All resulted in fines and costs.

And two months after this, with his two assistants and trusty van, Ebenezer junior was in Kettering, Nothamptonshire, where he found a new method of attracting attention … ‘… by holding a singing match for young women. There were ten competitors, and the prize, an electro-plated tea service. After all had sung, the audience decided, by a show of hands, that the best singer was a young girl named Fowkes, a view that some musical critics in the crowd did not coincide in’. (NM)

This attraction did not stop Ebenezer from regaling the local populace with more uncomplimentary talks on contemporary politicians and the monarchy. Unfortunately, one evening while he was absent from the van, a paraffin lamp was overturned and soon only its wheels remained — the rest was ashes!!

The van had also contained seven or eight watches awaiting repair … ‘these, it is alleged, some persons in the crowd kindly appropriated to themselves’. (LC)

‘Pulcifer seems to be of a cantankerous disposition, for every place he visits he sets the town on fire’…. metaphorically and literally?!!

But many had a soft spot for him and were not averse to his views. Some of his ‘Radical admirers and sympathisers’ formed an ad-hoc committee to ‘obtain subscriptions’ from the local factory workers and general public — and considering that the hawker was a stranger to the town they were ‘wonderfully successful. Such that….‘on Saturday last, at a public meeting held on the Market-square, Mr. James Toseland, on behalf of the committee, presented Mr. E. Pulcifer with a van for travelling which had been purchased at an outlay of £25, being the voluntary contributions of 500 of the working classes of Kettering, as a token of sympathy in his loss by fire recently, and for his plain openness of expounding his political principles’. (NM March 1880)

It was reported that an audience of 1000 persons attended the ‘ceremony’.

Benjamin Cope (1824-1904)

A story of widows and widowers, marriages and separations, legitimate and illegitimate children, drink and drugs, and a few premature deaths.

Another relatively long-term resident of Mount Row was ironworks labourer Benjamin Cope, born in Mapperley, Derbyshire.

His mother, Mary Keeling of West Hallam, was married to his father Samuel Cope, on May 23rd, 1824 at All Saints Church in Kirk Hallam. Benjamin was their first child, and six more followed before Samuel died in September 1838, as he returned from work. He had last been seen, late on a Friday/Saturday night, on his way home to Mapperley from Shipley, his route passing close by Mapperley Reservoir. By Saturday morning Samuel had not appeared home, leading Mary and Benjamin to go in search of him; when they reached the water a cheese was discovered on the bank and his hat in the water. Help was sought, the drags were called out and Samuel’s body was discovered shortly after. How it got into the water remained a mystery. There was speculation that he had perhaps had had too much to drink. He was reported to have two cheeses with him — perhaps he had dropped one into the water and, in an attempt to retrieve it, had slipped and fallen in.

Less than four years later — on March 20th, 1842 — at St. Alkmund Church, Derby, Mary married her late husband’s elder brother Richard, himself less than a year a widower. The couple had a daughter Mary, born in 1843, before Richard died in October 1851.

And so, on April 12th 1853, Mary married another recent widower — John Tatham, a lacemaker of Pimlico in Ilkeston — at Holy Trinity Church in Mapperley. The couple settled for a time in Chapel Street, Ilkeston, with some of Mary’s children, including Benjamin. John Tatham died on November 8th 1865 in North Street, Ilkeston, aged 70.

On June 3rd, 1874 Mary moved on to her fourth Church — St. Mary’s in Nottingham — where she married her fourth husband, widower Thomas White, who by then was aged 75. And just over two years later Thomas was dead … on December 10th, 1876.

Meanwhile Mary’s son Benjamin had found his own widow to marry. She was born Mira Roe, at West Hallam in 1825, the illegitimate daughter of Thomas Roe and Harriet Derbyshire (who later married in 1827). By the time Mira married her first husband, Samuel Mee, on December 28th, 1847, at All Saints Church in Kirk Hallam, Mira had her own illegitimate son — William Roe born in 1844 — and an illegitimate daughter, Harriet, with Samuel Mee born just before their marriage. (Are you following this ??) The Mee family then lived in Mapperley where two more daughters were added to the family.

Samuel worked as an ironstone getter at a Mapperley pit and was working there on May 18th, 1852, down a shaft about 150 feet deep. As usual he got into his iron basket or ‘tram’ to get to the surface, but about halfway up, for some reason he fell out of the ‘tram’. The fall severely and fatally fractured his skull. Samuel had earlier complained about a head pain and it was thought this might have affected his sense of balance.

Mira Lee now had four young children to support and she added to the number with another illegitimate daughter Mira, born in 1854, just before her marriage to Benjamin Cope — on December 26th 1854. (The father of Mira junior was most probably Benjamin). However the marriage didn’t last long and by the 1861 census Mira was spouseless and working in Mapperley while Benjamin was with his mother and her third husband in Chapel Street, Ilkeston. When the latter died in 1865, Benjamin and his mother found their way to Mount Row (though mother Mira took a detour via her fourth husband).

Mary White (formerly Tatham, late Cope, nee Keeling) died in April 1888, aged 88, (I believe she was then in the Basford Union workhouse) while son Benjamin was still living in, and working from, Mount Row. And he now had a housekeeper, widow Emily Constance Charlesworth (nee Forshaw) for company. She had been a nurse in the Burton Hospital but since about 1889 she had acted as housekeeper for Benjamin. She was described by the Nottingham Journal as “a woman of very respectable connections“, perhaps referring to her elder brother Thurstan Forshaw junior who was a medical practitioner in nearby Smalley, and to her late father Thurstan senior, who was Vicar of Newchapel Church in Staffordshire. For a long time Emily had been addicted to morphine (which she regularly injected), laudanum (to relieve the pain of an internal affliction) and narcotics (to help her sleep). When she ‘took a turn for the worse‘ in November 1893 a doctor was called but it was too late to help Emily. She was 48 years old.

By this time the Cope house in Mount Row looked out over a new Temperance Hall attached to the Bath Street Wesleyan Chapel.

Mira Cope, Benjamin’s estranged wife, died in 1901 by which time Benjamin had left Ilkeston to be housed at the Basford Union Workhouse, where he died in 1904, aged 80.

The Skevingtons

When Benjamin Cope and his mother had just moved into number 2 Mount Row, they found the Skevington family as neighbours at number 1.

Head of that household was widow Kezia Skevington (nee Housely or Yasley). Her husband George, whom she married on September 22nd, 1823, at Selston, Nottinghamshire, died in November 1838, aged 38. At that time Kezia was left with six young children to support, all born in Kirkby in Ashfield where the family then lived (and where George had died).

The all-female family came to Ilkeston about 1849 to settle initially in Bath Street before moving to Mount Row by 1871.

The youngest in the family, born in 1838, just a few months before the death of her father, was Eliza Skevington. It was while living in Bath Street that she had her first illegitimate child, Samuel, born in 1858 — possibly with furnace worker Robert Grebby. Her second child, Kezia junior, was born about 1862. Two marriages followed — to coalminer Benjamin Shaw in 1873 and then to widowed David Lebeter in 1882, at which point she left Mount Row to live in Factory Lane. Eliza died there — at number 6 — on August 16th, 1908, aged 69.

Eliza’s son Samuel Skevington however continued to live at Mount Row, got married in 1880 while still there, raised his family there, and at the turn of the century and beyond, was still there.

Let’s now switch our attention to Eliza’s illegitimate daughter Kezia Skevington junior. On June 6th 1881, she married coalminer Frederick Hallsworth and by the end of 1896 the couple had seven children, aged 12 years to seven months. At that time the family was living at number 5 Cambridge Cottages in Belvoir Street when they were visited by lnspector Cooper of the National Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Children**. He had been warned that the children were being continuously neglected and that is precisely what he discovered. This discovery led Kezia to appear at the Petty Sessions in November where an unpleasant picture of the Hallsworth domestic life was put on display.

The house was dirty and the children were lousy, with inadequate bedding and clothing for the cold weather. Their clothes were rags, black with dirt, and they had not a decent pair of shoes between them. Father Frederick was described by his employer at the Manners Colliery as having an excellent character, bringing home, on average, about £1 per week. The blame for the children’s condition and neglect fell squarely upon the shoulders of Kezia; to her neighbours she was ” a nasty drunken lowsy woman” who pawned her children’s clothing and household items to buy beer — often as much as 12 pints a day. Frederick pleaded that his wife was not as bad as the neighbours claimed; she liked half-a-pint of ale with her supper but no more. The magistrates however thought that they would “do the defendant a kindness” and separate her from her curse, viz., drink.

Kezia was sentenced to two months in jail, with hard labour.

Kezia served her sentence and then, out of prison, rejoined her family in Belvoir Street. But she wasn’t out of trouble. She now instigated a vendetta against a neighbour, Claire Leivers, who had provided evidence against Kezia at her previous trial. Claire was in fear of her life and appealed to the NSPCC for help. Kezia once more found herself in court and was bound over tp keep the peace for six months.

But Kezia had learned no lessons from her previous brush with the law and in October 1898 she once more faced the magistrates at Ilkeston Petty Sessions — charged again with neglecting her seven children, all still under the age of 16. She was still a heavy drinker and pawned anything she could lay her hands on to feed her habit. Husband Frederick was still powerless. The NSPCC once more prosecuted Kezia and once more she was sentenced to two months in jail with hard labour.

It was at this time that the eldest son, 12-year-old John William, was refusing to go to school. With his younger brother Francis, he preferred to play around the streets and light fires behind the theatre. His father Fredertick could do nothing with him and he exerted an evil influence over his ‘mates’. As a last resource the School Board obtained permission to send the lad to an industrial school until the age of 16. Was he the lucky one ?? A decision over a similar complaint against brother Francis was delayed for two months to see if his behaviour now improved. A glance at the 1901 census — showing Francis at the Industrial School in Birmingham — provides a clue !!

On February 2nd 1899 — the day when the two lads were due to be sent to the industrial school and George Cheetham, the school attendance officer had come to collect them — Keziah used some very choice language towards him, and found herself with another fine to pay.

Birmingham Industrial School in Gem Street

** the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SPCC) established centres in several English cities from 1883/4. In 1889 it was renamed the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) as it spread its branches over the U.K.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Tapley house

“The large three-storey house with quaint windows facing Bath Street came next. At one time this was Mr. Tapley’s school for boys. Mr. Tapley had a school in Bath Street, where he gave his boys a classical, mathematical and commercial education. I did not hear of him after 1859″.

The Bath Street Tapley family had its origins in Kent.

In 1814 John Keate — or Keet — Tapley married Mary Bilding Coveney in Borden in that county, and the couple had several children there before moving to Dartford where John worked as a schoolmaster.

About 1850 the Tapleys moved to Reading, Berkshire and there John taught at a Day School in East Street.

In the mid-1850’s they came to Ilkeston.

However sons Albert, born in 1827, and Octavius, born 1829, had beaten the rest of the family to it.

Albert had married Somerset lass Sarah Pearce in 1851 and shortly after that they arrived in Ilkeston where, in 1853, Sarah gave birth to their son who died in infancy.

Around 1851 Albert and Octavius were ‘drapers of Ilkeston’ when in May 1852 their partnership was dissolved.

The Post Office Directory of 1855 has Albert trading as a ‘linendraper’ at Somerset House in Bath Street. Was this Adeline’s ‘large three-storey house with quaint windows’?

And by March 1858 Albert was insolvent.

By 1861 the couple had left Ilkeston to live in Somerset.

In 1858 father John was using the Pioneer to inform residents of Ilkeston that he had taken the house opposite the Post Office in Bath Street ‘to teach young gentlemen’. The family also kept a draper’s shop there.

Although Adeline cannot recall John after 1859, he does make an appearance in the Harrison, Harrod & Co. Directory of 1860 as a schoolmaster of Bath Street.

And the family is recorded at Bath Street in the 1861 census.

With John and Mary are their unmarried son Edwin and their grand-daughter Sarah Andrews, daughter of James and Ellen (nee Tapley).

When John died in Bath Street in October 1862 the rest of the family left Ilkeston to return to Dartford and it was perhaps at this time that the Rice family moved into the Bath Street residence — which in 1871 was number 21 Bath Street.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

And here lived the Rice family.

Born in 1826 father in the Rice family was Joseph, general labourer and coal higgler, son of framework knitter Joseph Chadwick Rice and Hannah (nee Farnsworth).

He had married Catherine Lee, daughter of West Hallam cotton worker Marmaduke and Hannah, in December 1860.

Catherine’s three illegitimate children — German, Thomas and almost two year-old Eliza — came to live with the couple at Chapel Street.

By 1871 the family had moved to live in Bath Street and had expanded, with children Isaiah, Catherine and Lydia, while daughter Hannah had died in November 1863, aged 2.

Eventually in the 1890’s Joseph and Catherine moved into Chapel Street East — later Lower Chapel Street — and both died while living there in 1897.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Which brings us to Fletcher’s factory and the Wesleyan Church, on the map above, and standing opposite the Queen’s Head Inn.