After the shop of fishmonger William Henshaw, Adeline takes us to meet, not a firm of Dickensian lawyers but a trio of the town’s tradesmen ….

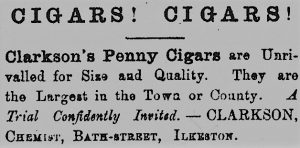

Simon Clarkson, chemist (1825-1908)

“Somewhere here was a private house occupied later by Clarksons, the herbalist.”

We are now opposite the premises of grocer Isaac Gregory (before he moved across the road) and Richard Riley’s Glass and China Warehouse, at what was 14 Bath Street in 1871 and 1881. (After the renumbering of the Bath Street shops in 1887, Simon was at number 37 Bath Street. And remember that from that time, all the premises on this west side of the street had odd numbers).

Born at Birstall near Bradford about 1825, Simon Clarkson was the son of grocer and chemist Richard and Harriet (nee Hopes?)

On the 1851 census he is a married wool comber, living on Birkenshaw Lane in Dewsbury, having married Elizabeth Smith in 1848.

In the later 1850’s he came south from Yorkshire, leaving behind his wife and son Thucydides, and settled in Mansfield for a time where he practiced as a ‘botanist and medical chemist’ in Queen Street of that town. By then he had three children … Hannah Mary (born 1848), Thucydides (1850) and Sandy (1854)

He was declared bankrupt in March of 1867 and discharged four months later.

In 1870 he was living and trading in Bath Street, Ilkeston, by which time he seems to have formed a relationship with Emily Lowe. She was the daughter of Bath Street schoolmaster William ‘Billy’ Pitt and Ann ‘Nanny’ (nee Rigley) and had married Joseph Lowe, lacemaker, on September 26th, 1852. Joseph had died on September 10th, 1864, by which time they had had seven children (one of them, Christopher, dying in infancy).

The couple lived in the North Street/ Chapel Street area of the town.

By the time her seventh child, Ruth Lowe, was born on January 9th, 1865, Emily’s husband was dead and she was left to support her six surviving children.

Her eighth child — and her first illegitimate child — was William Robert Lowe, born on January 27th, 1867, perhaps named after her brother and born at his Chapel Street residence. There followed other illegitimate children …. Harriet Ellen Clarkson Lowe (1870), then a daughter who died in infancy (1872), sons Galen Clarkson Lowe (after the Greek physician?) and Origen Clarkson Lowe (after the Greek theologian and philosopher?), born in 1873 and 1874.

Her last two children were daughters registered as Millicent (1876) and Nellie Clarkson (1878) by which time Emily was probably living with Simon in Bath Street as his ‘housekeeper‘.

Gap alert!

Simon’s wife Elizabeth remained behind in Yorkshire, living at times with her children.

Eldest child Hannah Mary Clarkson left Yorkshire and came to Ilkeston where in January 1868 she married Stapleford-born warp-hand William Doar.

The two Clarkson sons were Thucydides (after the Greek Historian?) and Sandy (after Alexander the Great? … a guess!)

I believe that Elizabeth died in 1874 (?), leaving Simon legally free to marry again. This he did on March 10th, 1880 when he married Emily. The marriage certificate shows Simon as a widower and Emily as a widow although she is listed by her maiden name ‘Emily Pitt’.

The couple were living at Chapel Street at the end of the century.

The compounds and potions of Simon advertised in the Pioneer were used extensively by Ilkestonians.

In 1870 the chemist reported that William Gallemore (sic) of Park Road had been cured of a bad leg after medical treatments had failed. He had previously attended two hospitals without relief, yet a course of eight bottles of one of Simon’s elixirs had done the trick.

from the Ilkeston Telegraph January 3rd 1874

By the early 1880’s Simon, ‘chemist, bone setter and tooth extractor‘, was promoting his wares via the front page of the Ilkeston Advertiser.

These included The Magic Paint and Purifying Pills for bad legs; The Golden Ointment for skin infections; The Camphorated Ointment for sores in the throat, on the hands, lips etc.; The Well-known Ointment for boils, burns and scalds; The Absolute Tincture for toothache, rheumatism and sciatica; and Female’s Friend to sooth teething children.

Simon could also supply remedies for Fits, Consumption, Coughs and Colds, King’s Evil (Scrofula), Cramps, Cholera, … you name it and he could cure it!!

And note also that “patients can be treated according to Allopathic rule or by the new light, namely, Homoeopathy”

Like father, like son ??

As outlined above, Emily Lowe (nee Pitt) had several illegitimate children, the first one being William Robert Lowe alias Clarkson who was born in Chapel Street on January 22nd, 1867. On April 3rd 1886, he married Mary Ann Attenborough under the name of ‘Clarkson‘ and gave his father’s name as Simon Clarkson, chemist’; his bride was the daughter of coalminer Edwin and Maria (nee Thorpe). By 1891 Mary Ann had given birth to two daughters and was living with them but without her husband, who had deserted his family. On the 1891 census he was living in Wood Street, now under the name of William Lowe, lodging with his half-sister Elizabeth (nee Lowe) and her husband Frederick Webster.

His desertion led to a maintenance order, dated September 1st 1892, being made against him; he now had to pay 9s a week for the upkeep of his wife and two daughters. William was not pleased !! In April 1894 he went to court to have the payment reduced … he just wasn’t earning enough to pay that amount. Mary Ann retorted that he had enough money to take other women to the theatre and to Nottingham !! The magistrates at the Petty Sessions declined to take pity on William !!

Just over two years later — in July 1896 — William was back at court, but this time not because he wanted to … he had been summoned by his wife. Since May he had been deducting 3 shillings per week from his maintenance payment to his wife (presumably on the assumption that if the Court wouldn’t comply with his request he would take matters into his own hands ?). Mary Ann was not best pleased by this state of affairs and reckoned the William now owed her £1 1s.

The couple had been living apart for seven years now but Mary Ann had just given birth to a child (John Arthur Clarkson) on May 29th. William now got his mathematical brain to work. When he separated from Mary Ann they had two legitimate children, daughters Harriet and Ruth; now there was a child who wasn’t his … so he had divided the 9 shillings into three parts and had then deducted a third for the illegitimate child.

However, while separated, William had made infrequent ‘casual visits’ to see his wife; she claimed that during one of them, John Arthur had been conceived. The Petty Sessions Court was inclined to believe Mary Ann, and William was left frustrated and poorer once more.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

George Tooth, currier. (1831-1888)

“Mr. George Tooth, leather merchant, had the next shop”. (15 Bath Street in 1871).

The job of a currier, preparer of leather — “In the Victorian era tanneries were often close to the abattoirs and so the skins would often arrive at the tannery fresh and unsalted. Regardless of this the skins still needed to be washed to remove the dirt off the skins and to do this the skins would be soaked for up to 12 hours and in tanneries close to rivers they often used the running water to clean the skins. The process over a beam of unhairing skins was much slower and gentler. The skins were soaked in pits in a solution of lime on its own. Traditionally very weak solutions were used and the skins could be in the lime for 1-2 weeks for small skins to several weeks for heavier hides, although there was a move to stronger lime solutions and immersion for only around a week by the late 1800s” (From J. Hewit and Sons: A Company History)

Curriers in the tannery (From J. Hewit and Sons: A Company History)

Born in 1831 George Tooth was a son of Derby shoemaker Charles and his second wife Elizabeth (nee Thorley?)

Married to Emma Toogood Radford at Derby in September 1855, currier George began his business in Bath Street in 1858, having arrived in the town with his wife and daughter Alice.

Three further children were born here…. Charles (1859), Mary (1860) and Frank (1861). And three children died and were buried here…. Charles (aged 9 months), Mary (aged 3 days) and Alice (aged 4 years).

At the marriage of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, to Princess Alexandra Carolina Marie Charlotte Louise Julia of Denmark in 1863 George ‘liberally gave 72 quarts of good ale’ and a subscription, to supply to the poor of the town. (Trueman)

George left Ilkeston with his wife and son Frank in July 1867 to live on the Esplanade in Nottingham.

Within two months of his arrival in the city he was summoned for non-payment of a poor rate which should have been made in April. George went down to the rate office to sort out the problem, claiming that he had only lived at his house since July 25th but William Simons, the town rate collector, was in no mood to compromise.

‘They always summons such persons as you that won’t pay’ was his provocative argument. Standing before the rate collector in his working clothes, George declared that he had always paid his rate promptly, to which William sneered ‘You look as if you pay rates the first time’.

The conversation became increasingly fractious with William being especially belligerent and insulting towards George. The latter was pushed out of the office, struck at the side of the head and, worst of all, had his hat crushed in the process!!

Needless to say, this behaviour landed William in the police court where he pleaded provocation — George had been very impertinent and had caused a great deal of annoyance.

This did not save the rate collector from a fine of 20s however.

George continued to live in Nottingham and for many years kept a shop in Mount Street in that city, though he maintained a contact with Ilkeston. His ‘agent’ there was Alfred Henshaw, bootmaker of East Street, who in 1880 received a visit from Captain Sandy, inspector of weights and measures. The Captain found that Alfred was using unstamped weights in his trade and this landed George ‘in the dock’ at Ilkeston Petty Sessions. The currier had acquired the weights for Alfred and argued that his agent should have got them stamped… an argument which did not wash with the magistrates.

By 1887 the Tooth family was living at Park Place off Park Row …. and through ‘ill health, bad debts and bad trade‘ George’s financial position was very precarious… and not for the first time. The currier had assets of just over £900 but debts of three times that amount. The Official Receiver declared him officially bankrupt !!

It appears that George was correct about his ill health…. he died in the following year.

George was the half-brother of Mary Tooth who married miner James Bonsall of Bonsall Place, off Bath Street.

The Ilkeston premises vacated by George in 1867 were subsequently occupied by cordwainer William Prince and in May 1869 were put up for sale by auction at the Old Harrow Inn. William the cordwainer was still at the premises after the auction, at least until 1874, and by 1881 the shop was occupied by draper William Joseph Pyefinch and his family. By the mid-1880s John Newton, a saddler, had taken on the property when it was renumbered as 39 … and John was still there almost to the end of the century when it was then occupied by boot dealer William King.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Eliezer Pickburn, plumber (1815-1895)

“Below was Mr. Pickburn, the plumber. He afterwards took one of the new shops in the Market Place”. This was 16 Bath Street in 1871. (though later, in 1887, renumbered as 41)

Eleazar — or Eliezer — Pickburn was the son of John and Martha (nee Bowler), born at Eastwood in 1815, though the family resided at Sutton in Ashfield where John worked as a framework knitter and later as a coal higgler.

It was there in November 1838 that Eleazar married Martha Ward, daughter of Joseph and Mary (nee Straw), and the couple arrived at Bath Street about 1840 with daughters Ann and Emma.

The 1841 census locates the family in Bath Street – but no Emma! She had died in Ilkeston in January of that year, aged one.

The family then grew with the addition of John the first (died in childhood in a scalding accident), Eliza, John the second, Hannah, and twins Martha and Mary (both died in infancy).

In June 1858 wife Martha died, aged 47.

Six months later Eleazar married Emma (nee Beard), the widow of railway worker Charles Garrett and daughter of Joseph and Mary – a marriage that was subsequently to cause Eleazar much grief.

In 1861 Eleazer seems to have moved into the Market Place, so that, according to Adeline, for a few years in the 1860s “Mr David Pressland, cabinet maker, followed in the Bath Street shop”. We have already met David Pressland in South Street. Then, in early 1867 the tinman and his family moved back into Bath Street, to premises opposite Scales and Salter, boot and shoe manufacturers.

Eleazer’s second wife Emma had at least three children by her first marriage. One of these was her son Thomas Garrett, born in Derby in 1850, who had come to live in Ilkeston with his mother and Eleazar after their marriage. What a blessing !!!

… step-son Thomas Garrett (1850-?)

“Life is a game, boy. Life is a game that one plays according to the rules” ….. J.D. Salinger Catcher in the Rye

In January 1869 Thomas was accused by his step-father of stealing four skirts, three dresses, two shawls, and one chemise from the family home while Anchor Carrier, a miner aged 17 and friend of Thomas, was accused of receiving the stolen goods.

It was claimed that Anchor had taken the stolen goods to the pawnshops of Thomas Foster Weatherhogg in Victoria Terrace, Granby Street and of John Moss in South Street.

In defiance of fairly robust identifying evidence both youths pleaded their innocence and were sent to trial at the assizes. Here they pleaded guilty and were sentenced to three calendar months with hard labour.

If he hadn’t been before, Thomas was now on very bad terms with his step-father and mother.

In the following year — while Mary Loftus was ‘drunk and riotous’ in Bath Street — Thomas was perhaps accompanying her.

What is certain is that shortly thereafter he was at the back of his step-father’s property, breaking eight panes of glass.

He was then back in court where he was described as an ‘idle vagabond’.

And then he was back in jail for a further two months with hard labour.

At the trial his unsympathetic mother Emma ’stuck the knife in’, declaring that the stones which Thomas threw at the windows may have killed her husband if they had hit him, as the latter was laid up by lameness after being run over with a cart.

In June 1871 another stealing offence for Thomas and a very unusual situation for Paul ‘Paulie’ Bostock junior. The latter was in court but this time as the ‘prosecutor’ and not the defendant!!

He had been out drinking with Thomas Garrett and Amos Beardsley when a half crown fell out of his pocket. Thomas picked it up and slipped it into Amos’s boot. Paul complained and the three were carted off to the police station where a search revealed the money.

Like an upright citizen Amos thought it judicious to give evidence against his ‘mate’ Thomas and escape any charges.

The result for Thomas however was a 12 month prison sentence. His prison record at this time indicates that he was 5 feet 4½ inches tall, with brown hair, grey eyes, a pale, pockmarked face bearing scars on his forehead, over the right eye and cheek, with a blue mark at the left side of his nose.

On his release from Derby Prison, in June 1872, Thomas returned to his former lodgings at the house of William Trueman of 14 Club Row.

A few months passed and Thomas now felt in need of a change of clothes — a new and better ‘wardrobe’.

Consequently he acquired a black cloth coat, value 30s, a black cloth waistcoat, value 10s, and a pair of black cloth trousers, value 20s. To complete the ensemble were a muffler and scotch cap.

This ‘makeover’ didn’t cost Thomas anything however — he stole all of the items from his fellow lodgers, Arthur Garner and Edward Davis, both of whom discovered their loss just after Thomas had made an abrupt departure from the lodgings in Club Row.

But Thomas was never very good at evading the law for too long and quickly found himself in custody.

In April 1873 his appearance at Derby Quarter Sessions and a subsequent guilty plea brought a sentence of penal servitude of seven years at Chatham convict prison with three subsequent years of police supervision.

In April 1879 he was released on license to return to Ilkeston.

The sentence of penal servitude was initially introduced in 1853 as an alternative to transportation in certain cases and after 1867 was used instead of all transportation.

A prison sentence with hard labour would be served in this country rather than in the Australian colonies with the possibility of early release for good conduct. The prisoner would then be freed on licence or ‘ticket-of-leave‘.

Thus by 1879 Ilkeston was once more blessed with Thomas’s presence — now a ticket-of-leave man, under four years’ police surveillance, with a duty, under the law, to report to the police on the first of each month.

Thomas kept this up for about four months.

Then there were reports of him wandering the town at night, loitering around houses, trying their shutters. Sergeant Colton then discovered that Thomas had not been at his lodgings for ten weeks but his defence was that he had gone to the Mansfield district in search of work.

By September he was charged with not reporting himself to the police at Ilkeston.

The Bench at Heanor Petty Sessions thus decided to return Thomas to prison to serve the remainder of his sentence.

In October of the following year and out once more, Thomas again came into the district but again failed to report to the police although he was under police supervision. Thus he was sent to prison for six months with hard labour.

This is why the 1881 census lists him at Her Majesty’s Prison, Vernon Street, Derby.

A month after this, out of prison again but under police supervision, Thomas was picked up at Ilkeston for vagrancy and imprisoned for a month.

In July 1881 Heanor had the pleasure of hosting not only Thomas Garrett but also Solomon Skevington and Paul Bostock senior.

In one group!!

“Three powerful looking men.. and well-known characters in Ilkeston”

A more toxic and troublesome trio one would not wish to meet.

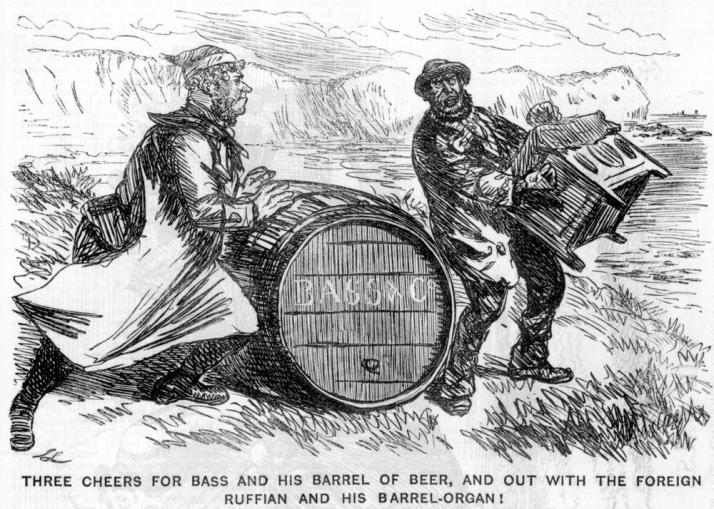

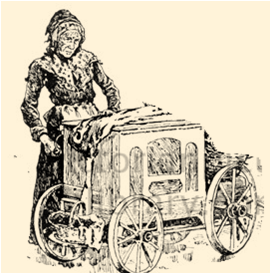

At about lunch-time the three of them rolled out of the Horse and Jockey Inn on Mansfield Road in Heanor – perhaps much to the relief of innkeeper John Glazebrook – and almost immediately encountered a group of four Italians playing a barrel organ.

Clearly not a lover of organ music nor of Italians, a drunken and aggressive Paul attacked the group while Solomon was quick to join in. Meanwhile Thomas started to dismantle the musical instrument in a most aggressive manner. A witness reported that in the mêlée which followed Paul struck the female operator who fell bleeding and unconscious to the ground whereupon Solomon then ‘put the boot in’.

Antonelli barrel organ 1909 (Anthony Rea)

A week later the three Ilkestonian ‘amici’ appeared at Heanor Petty Sessions where Paul and Solomon were convicted of assault and sentenced to three months in prison with hard labour.

On this occasion – a novelty for him? – Thomas was found not guilty of the assault charge although he did not walk free from the court.

The organ belonged to Antonio Cassinelli, a ‘jolly, robust’ ice cream dealer from Sheffield, and had been broken to pieces, or as Antonio described it, via his interpreter Jackomo Solari, …..

“It is not broken one way but all ways. Ze top is gone, ze bottom is gone, ze sides is gone, and ze inside is gone”.

The organ had cost him £18 and he calculated that £5 worth of damage had been done.

Thus, for his part in the organ assault Thomas was fined £5 with £5 damages and 19s costs, but as he could not – or would not – pay he was imprisoned for two months, with hard labour.

So as well as incurring the loss occasioned by the damage to his organ, Antonio had to pay his own costs for the case which he did ‘willingly’ — though as he left court, he made a few remarks about the peculiarity of English law in such a case as this.

In May of 1882 Thomas again failed to report to the police and was rewarded with another six months with hard labour.

With the sentence served and at large again, who should Thomas search out but his old mate Paul Bostock senior.

Having charged themselves with drink the couple felt peckish and so made their way to Lower Granby Street and the home of William Nunn, relieving officer for the Basford Union … for some relief!! William was not at home but his wife Catherine Annie (nee Sanders) was.

The drunken pair walked into the house, refused to leave and demanded refreshments, reinforcing their request with threats against the terrified Catherine who was forced to accede.

Of course, they were to pay eventually for their impromptu dining. At Ripley Petty Sessions they were charged with vagrancy and each committed for one month.

For Paul this was Number 63 !!

A year later .. October 1883 … and the same pair were in the same condition, tottering down Bath Street.

Another appearance at the Petty Sessions .. this is becoming monotonous!! … and another month in prison with hard labour for Paul (Number 66) while Thomas got half that.

Gap alert! What happened to Thomas after this?

There is a report in the Nottinghamshire Guardian of January 1886 labelling ‘Thomas Garrett and Henry Watson’ as ‘Workhouse Bad Characters’ who were accused of trying to steal a sheet from the Basford Workhouse with some associated violence on the part of Thomas. The result was a month in prison.

“Garrett had been in prison or the workhouse nearly all his life”.

And Eleazer again.

In October 1876 Eleazar Pickburn’s second wife, Emma, died aged 48, and in April of the following year he married spinster Mary Hannah Wroughton, the daughter of Repton baker John and Frances (nee Rees).

In 1879 Eleazar was accused of being drunk in charge of a horse.

Returning from Sandiacre Wakes in September, he appears to have had difficulty in guiding his horse and trap up Nottingham Road, past Kensington, and was thrown from the vehicle, cut his face, struggled to regain his composure, and then used threatening and abusive language towards a ‘helpful’ P.C. Aldwinkle.

Of course the gas-fitter denied that he was ‘fresh’, having drunk only two glasses of ale but he was fined nonetheless.

The Pioneer placed the fault for the accident squarely upon the shoulders of the Local Board, especially its Surveyor – where else?!

Board workmen had left a heap of soil in the roadway when they should have cleared it away, and it was this heap which had caused Eleazar’s trap to overturn.

Two labourers were subsequently dismissed – but what about the Surveyor pointedly asked the Pioneer?!

In December 1880 the police came calling at Eleazer’s Bath Street premises and started a spot of gardening in his back yard, where they quickly found a buried silver watch, the property of lacemaker George Scattergood (alias Calladine).

A few days earlier the latter had wanted some gas fittings installed in his Market Street home and Eleazer sent round his employee, a youth named Albert Smith to carry out the work. A couple of days work and the lad was gone — but so was George’s silver watch!!

The lacemaker put two and two together and came up with the correct number. The police hauled in Albert who subsequently confessed and revealed where he had stashed his loot.

Directories and the census place Eleazar in Bath Street for most of this time and until Mary Hannah’s death in July 1883, he was trading as a brazier and tinman, and later as a gas-fitter.

In May 1888 the tinman’s Bath Street house and shop plus outbuildings (then number 41 Bath Street) — over 280 square yards — was sold at auction to Breaston solicitor William John Watson for £1025. And now a widower for the third time, Eleazer retired to live in Smalley with his step-daughter Frances Wheatcroft Wroughton, his late wife’s illegitimate daughter.

The premises were shortly taken over by John and Susan Wicks, and for a brief period the latter traded as a tobacconist there. By 1894 another tobacconist John Davison, moved in and was still there at the Victorian era drew to a close.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

At the end of the nineteenth century

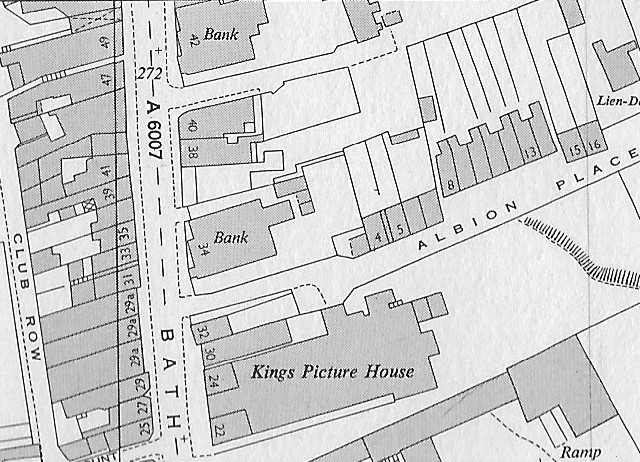

To help you get your bearings, you are standing at number 41 Bath Street. If you glanced across Bath Street in 1901 you would see, at the corner of Albion Place, the Crompton and Evans’ Union Bank Limited building (which had recently been erected on the site of the old Alms Houses). This was at number 34 Bath Street.

A few doors further down (northwards) is another bank — Samuel Smith and Co. at number 42.

By August 1897 the Breaston solicitor William James Watson (mentioned above) was a bankrupt and so his two saleshops numbered 41 and 43 which he had purchased in 1888 were once more auctioned off. At that time they were occupied by tobacconist John Davison (number 41) and by James Godber, painter and house decorator (number 43). At the auction the properties were purchased for £990 by the tobacconist.

The neighbour to the north of the two properties was the shop of draper John Carrier (number 45), while to the south it was William Brotherhood, wallpaper dealer. In April 1898, John Carrier’s shop and house were put up for sale by auction. The property consisted of a three-storey dwelling house (with entrance hall, dining room, drawing room, kitchen, scullery, larder, seven bedrooms, and three rooms in the attic) and John’s draper’s shop — John had traded there for the last 14 years. (The property was withdrawn at the auction when it failed to reach its reserve price).

John was born in Ilkeston on October 19th, 1840, the son of framesmith/mechanic John senior and Mary (nee Starbrook), and had married Sarah Beardsley on October 6th 1869. Sarah was the illegitimate daughter of Mary Beardsley and had been born on November 25th 1843 when, interestingly, she was registered under the name of Ruth — at her baptism, seven weeks later, she was ‘Sarah’. Her mother Mary later married grocer Samuel Lowe of East Street and later South Street.

At the time of this sale it would appear that the seven bedrooms were needed for the Carrier couple and their six surviving children.

At the north edge of the above map you can see number 49 Bath Street — in April 1898 this too was up for sale by auction, when it was occupied by grocer and provision merchant Alfred Burton Wood. It was hyped as “perhaps the best business premises in Ilkeston“, a shop and house thoroughly well-built, and fitted with every convenience for business.; the property included a garden, greenhouse, stable and coach-house to the rear. As an added bonus there was a licence to sell wines and spirits attached to the premises, with extensive celler facilities. Alfred had been there since 1885 but was now retiring from trade through ill health. (At the auction it failed to reach its reserve price and was withdrawn).

In the same lot at auction was its neighbour number 51 Bath Street, a house then tenanted by house joiner William Fogg, but “suitable for conversion into business premises”

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

And now some short-term residents.