And the other children of John and Elizabeth Columbine?

1. John Columbine junior.

Like his father, John junior also left Ilkeston for Nottingham and there he married Mary Elizabeth Toon in 1879. She was the daughter of whitesmith Thomas and Eliza (nee Clarke).

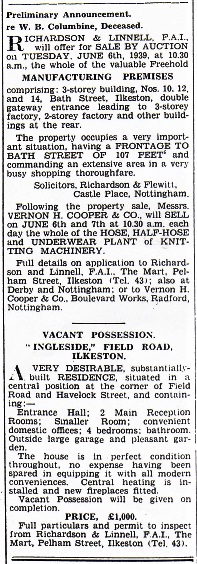

In her definitive study of the East Midlands lace industry, Sheila Mason states that the Bath Street industrial complex of Henry Carrier & Sons was taken over by John Columbine junior in 1902 and thenceforward concentrated on hosiery.

2. William Brailsford Columbine.

All his working life William Brailsford Columbine was connected with the hosiery trade.

At Nottingham on August 1st 1876, he married Fanny Claringburn, daughter of Nottingham framesmith Joseph Augustus and Martha (nee Peet). The couple lived in Bromley Place in Nottingham, where William was a warehouseman.

Their children, Ernest Oswald, Harold Brailsford, Minnie Adeline and Edith Frances, were born in the city.

From 1891 to 1908 the family was at 14 Curzon Street in Nottingham.

The family then moved back to Ilkeston to live at Ingleside in Field Road, (telephone Ilkeston 141). !!

In 1904 William took over the business of Henry Carrier & Sons Ltd, hosiery manufacturers of Bath Street, and up to the time of his death he was its owner and also Managing Director.

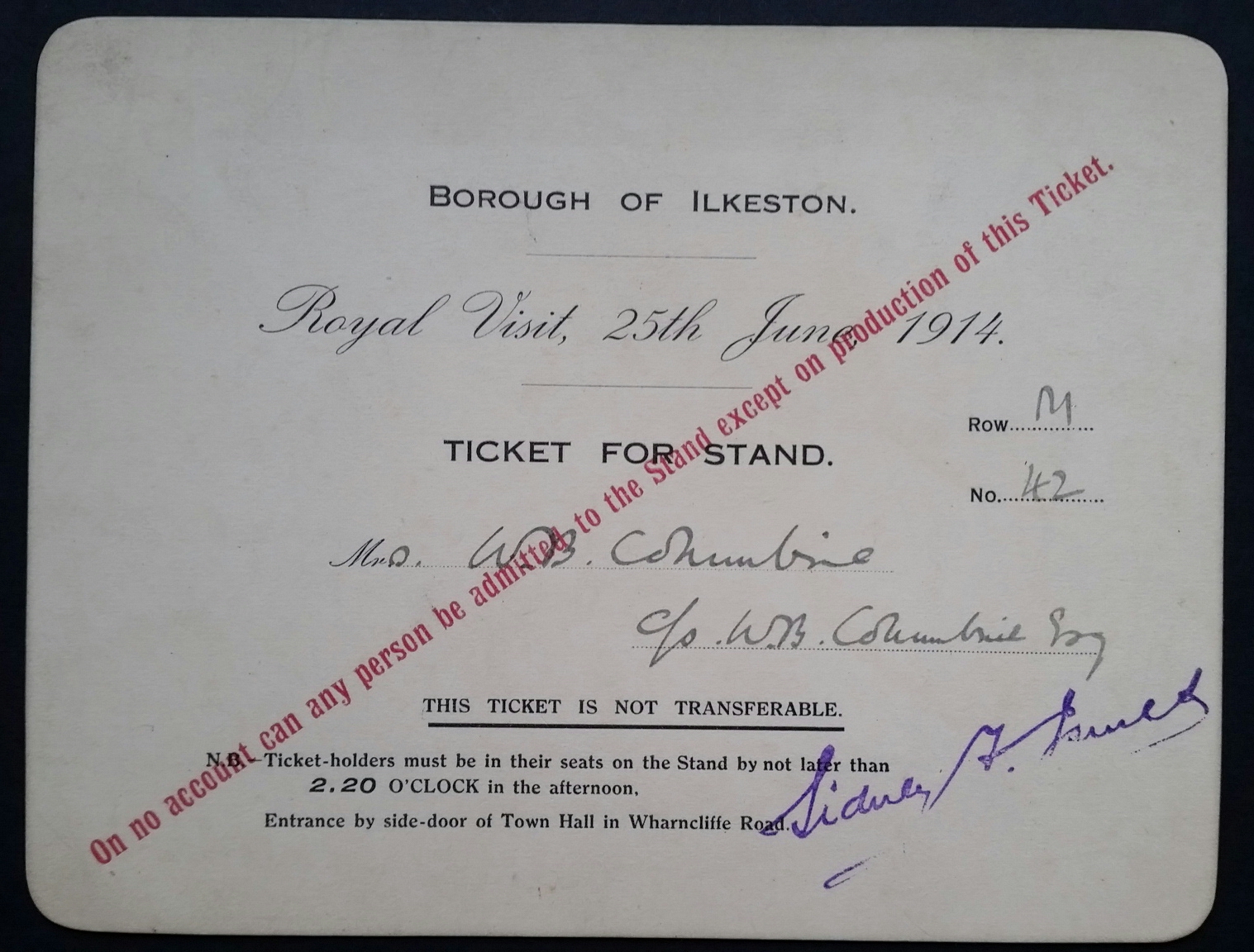

From the collection of Andrew Knighton

Fanny died at the family home of Ingleside in Field Road on February 23rd 1921, aged 66, and on December 12th of the following year William Brailsford married his second wife, Florence Barrowcliffe, daughter of lacemaker James and Alice Hannah (nee Keightley).

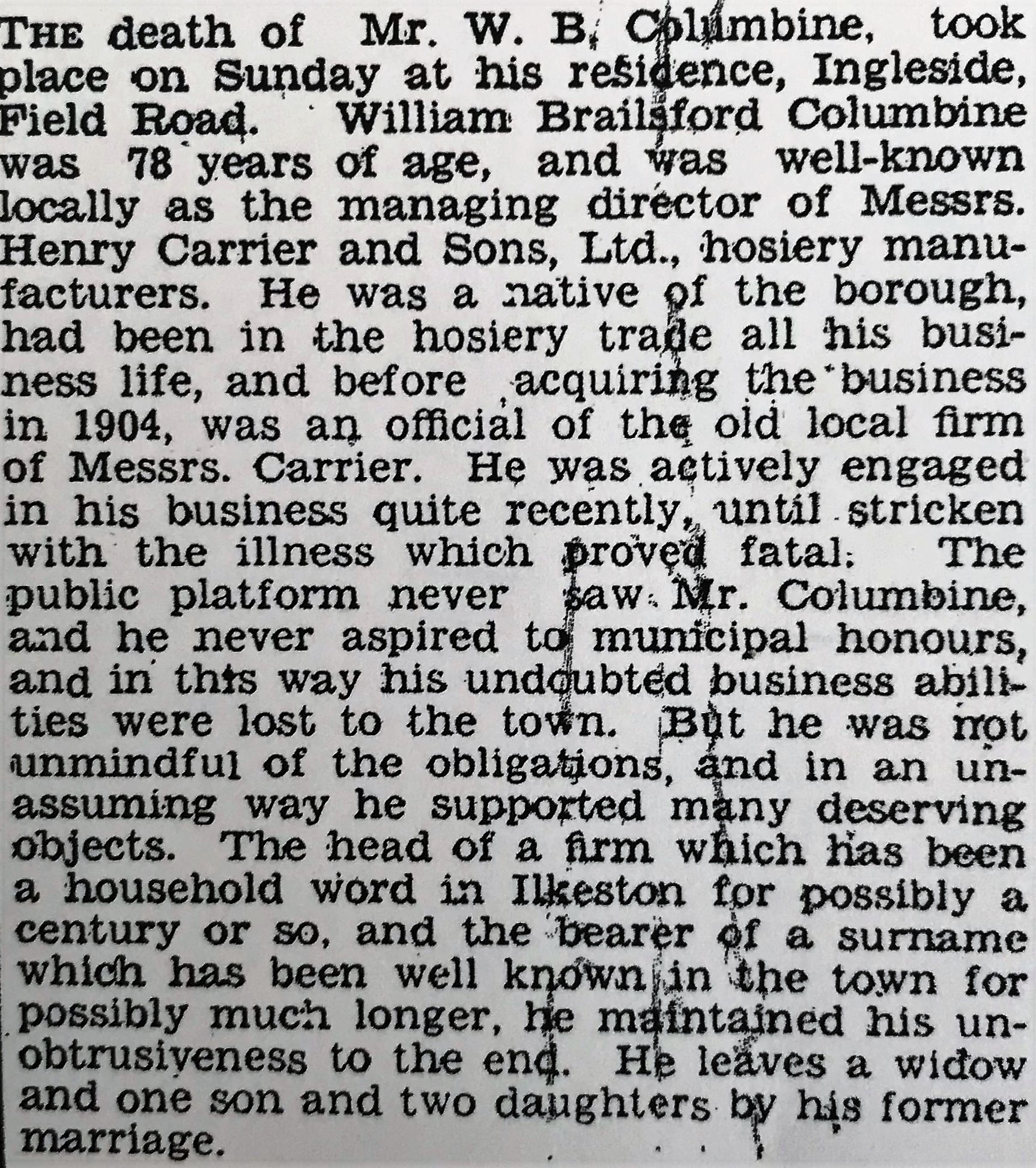

Suffering a recent bout of acute bronchitis, William Brailsford died at Ingleside on December 5th, 1937, aged 78.

The Advertiser described him as a generous supporter of good causes in Ilkeston. He was ‘a man of more than ordinary intellectual gifts’ and ‘will be greatly missed by many whom he has helped in various ways’.

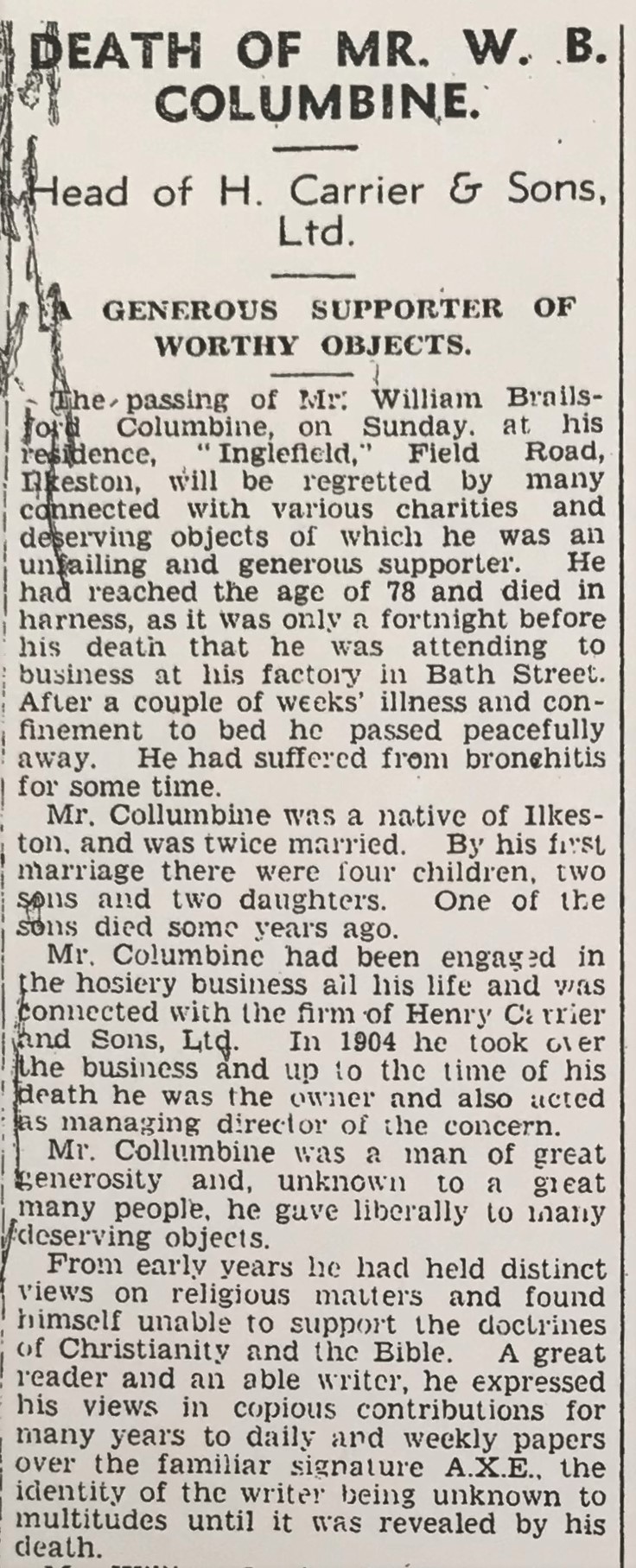

In an obituary article the newspaper added a little detail about his personal beliefs.

“From early years he had held distinct views on religious matters and found himself unable to support the doctrines of Christianity and the Bible. A great reader and an able writer, he expressed his views in copious contributions for many years to daily and weekly papers over the familiar signature A.X.E., the identity of the writer being unknown to multitudes until it was revealed by his death”.

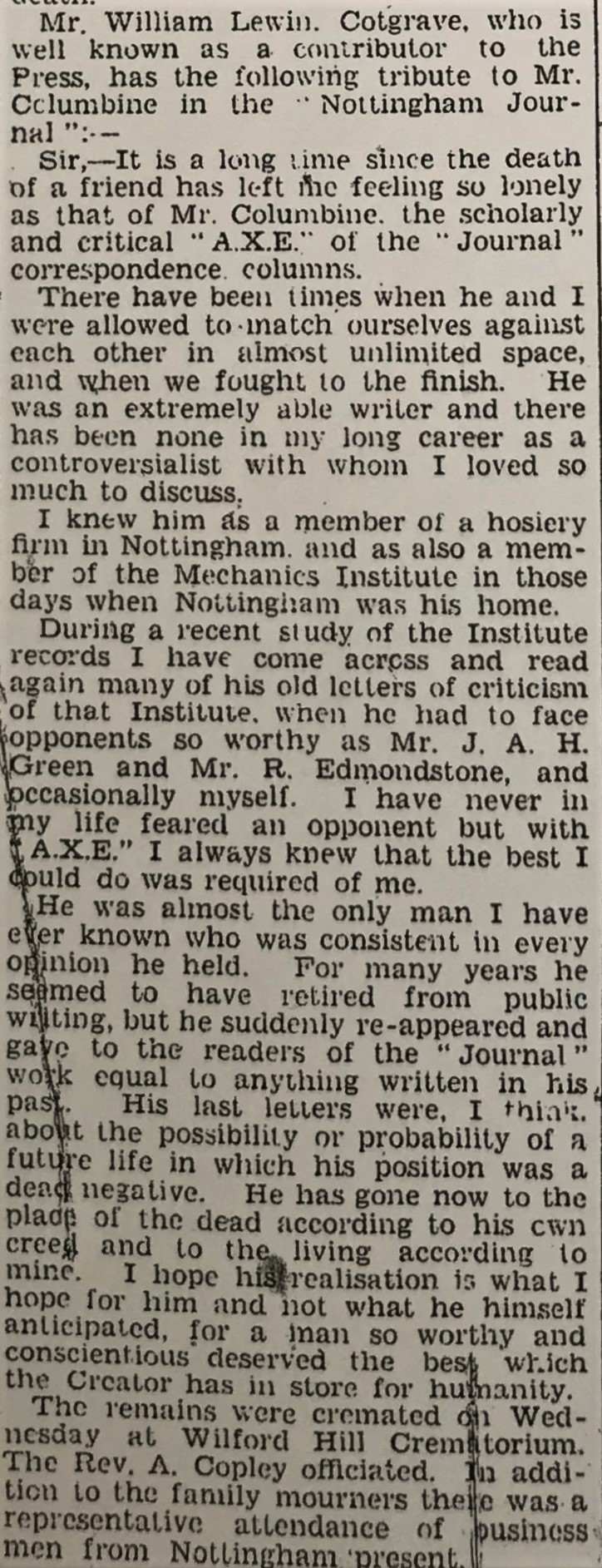

His friend and fellow newspaper contributor, William Lewin of Cotgrave, wrote in the Nottingham Journal;

“He was almost the only man I have ever known who was consistent in every opinion he held. For many years he seemed to have retired from public writing, but he suddenly re-appeared and gave to the readers of the ‘Journal’ work equal to anything he had written in his past. His last letters were, I thought, about the possibility or probability of a future life in which his position was a dead negative. He has gone now to the place of the dead according to his own creed, and to the living according to mine. I hope his realisation is what I hope for him and not what he himself anticipated, for a man so worthy and conscientious deserved the best which the Creator has in store for humanity”.

Left is the article from the Ilkeston Advertiser, Friday, December 10th 1937. (Columns 1 and 2). Right is the article from the Ilkeston Pioneer, same date.

——————————————————————————————————————

Shortly after (January 7th, 1938), a eulogistic letter (transcript below) appeared in the Ilkeston Advertiser, written by Richard Benjamin Hithersay (RBH, whose address then was 26 Malfort Road, Denmark Park, London, S.E.6)

|

The late Mr. W. Brailsford Columbine (by an Old Friend) Sir, — It was with something of a shock that I read in a recent issue of a London paper an announcement of the death on December 5th of Mr. Columbine. He was a very remarkable man, and, as a fellow-Ilkestonian and old friend – probably the oldest – I should like to pay a tribute to his memory. I first made Mr. Columbine’s acquaintance nearly 60 years ago when, as a boy fresh from school, I entered the service of a firm whose warehouse was in Nottingham. Mr. Columbine, who was then about 19 years of age, had already been there for several years. I was placed straight under his charge, and for six years — until I removed to London – he was not only my office superior, but my “guide, philosopher and friend”. Even at that distant date I soon discovered that his real interest in life was not the making of money in business but the war against superstition and the advocacy of the principles of materialism. Charles Bradlaugh was then, and has remained through life, his ideal. To these principles and this ideal Mr. Columbine had adhered with unswerving consistency throughout his long career. Incidentally, he soon converted me – a descendant of a long line of Calvinistic Baptists – to his views on orthodox or any other formulated religion, although he always failed to convince me that body and soul are one entity and that nothing survives for the individual after death. His own consistency is shown by the fact that as recently as May last he wrote me the longest letters I have ever had from him, all arguing in support of his life-long creed. As far back as 1877 he was contributing copiously on freethought matters to the correspondence columns of the ‘Nottingham Journal’ – then I believe under the editorship of the late Sir John Barrie – and as recently as two years ago he and I discussed at some length in its columns the question: “Do we live again?” he, of course, taking the negative view. During the last 60 years the ‘Journal’ has contained innumerable, and sometimes very lengthy, contributions from his pen, mostly under the signature ‘A.X.E.’, practically all of them in support of the heterodoxy in which he believed. In addition to the work in the ‘Nottingham Journal’ he was writing frequently to the recognised freethought papers – the ‘National Reformer’, edited by Bradlaugh, and the ‘Secular Review’, edited by Charles Watts and Stewart Ross (‘Saladin’). He was also a regular contributor for many years to the ‘Literary Guide’, the representative organ Rationalist (modern Freethought) party and some years ago he wrote and published in book form a well-reasoned reply to Balfour’s ‘Philosophical Doubt’. All this in addition to his business activities, which, in the peculiar circumstances attending the fortunes of the firm in the services of which he spent his life, must have absorbed much of his attention. In short, he was the most indefatigable and conscientious worker I have ever known. Handicapped from the start by a far from robust constitution, he could not have accomplished half so much if he had not conserved and utilised every particle of energy he possessed, if his mind had not been so rigidly disciplined and if he had not kept his brain like a well-oiled and perfectly running machine. He was very reserved and uncommunicative, and I should think that few people in Ilkeston had any idea of his multifarious activities. His literary style was good, without any pretentions to artistry or brilliancy. Everything he wrote was lucid, logical, and convincing. As a controversialist, he was admirable. He never allowed himself to show irritability and never attempted to score over the most stupid of his opponents by holding him up to ridicule. He never gave way to impulse and was very unemotional, outwardly at least. He was no disciple of Omar Khayham, and I cannot imagine his saying with Landor: “I have warmed both hands at the fire of Life: But I can believe that he met his death with philosophic and Socratic serenity, and went to his final sleep |

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

1 Wikipedia defines Freethought as ‘a philosophical viewpoint that holds that opinions should be formed on the basis of science, logic, and reason, and should not be influenced by authority, tradition, or any other dogma’, especially in religion.

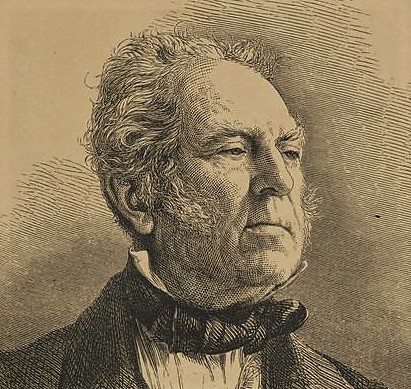

2 In 1860 Charles Bradlaugh (right) helped form the journal the ‘National Reformer’.

This was based on atheistic Secularism.

He spoke out on such issues as universal suffrage, contraception and republicanism.

He then helped found the National Secular Society in 1866.

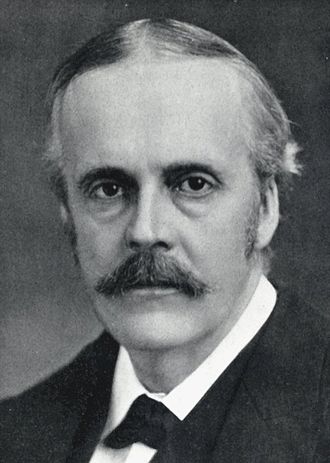

3 Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905, Arthur James Balfour (left) was also a renowned philosopher.

In 1879, he wrote ‘A Defence of Philosophical Doubt’.

William Brailsford wrote his critical examination of Mr. Balfour’s Apologetics in 1902.

4 The letter’s first two lines of poetry are taken (not with total accuracy) from Warwick-born writer (right) William Savage Landor’s work ‘On His Seventy-fifth Birthday’ (1849).

The letter’s last two lines of verse are the last two lines of the poem ‘Thanatopsis’ (meditation upon death), written in its final form in 1821 by American poet William Cullen Bryant.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

William Brailsford’s estate, with a gross value of £55,131 12s 6d, (net 21,394) was inherited by his widow and surviving children. He was cremated at Wilford Hill Crematorium in West Bridgford.

A large memorial column stands in Park Cemetery in his memory as well as that of his first wife Fanny, their son Harold Brailsford Columbine and Harold’s wife Jane Charlotte (Cissie).

From the Ilkeston Advertiser May 1939.

William’s widow, Florence continued to live at 2 Field Road for a time. She died at Cedar Lodge, in the Park, Nottingham on March 12th 1986.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

3 Martin Webster Columbine.

Martin Webster Columbine married Catherine Mary Giles at Lowdham on June 2nd 1883 and for a time remained at Nottingham, where daughter Ethel Gertrude was born in 1884 and son Arnold Martin in 1887.

In the late 1880’s he returned to Ilkeston to live at 7 Albert Street.

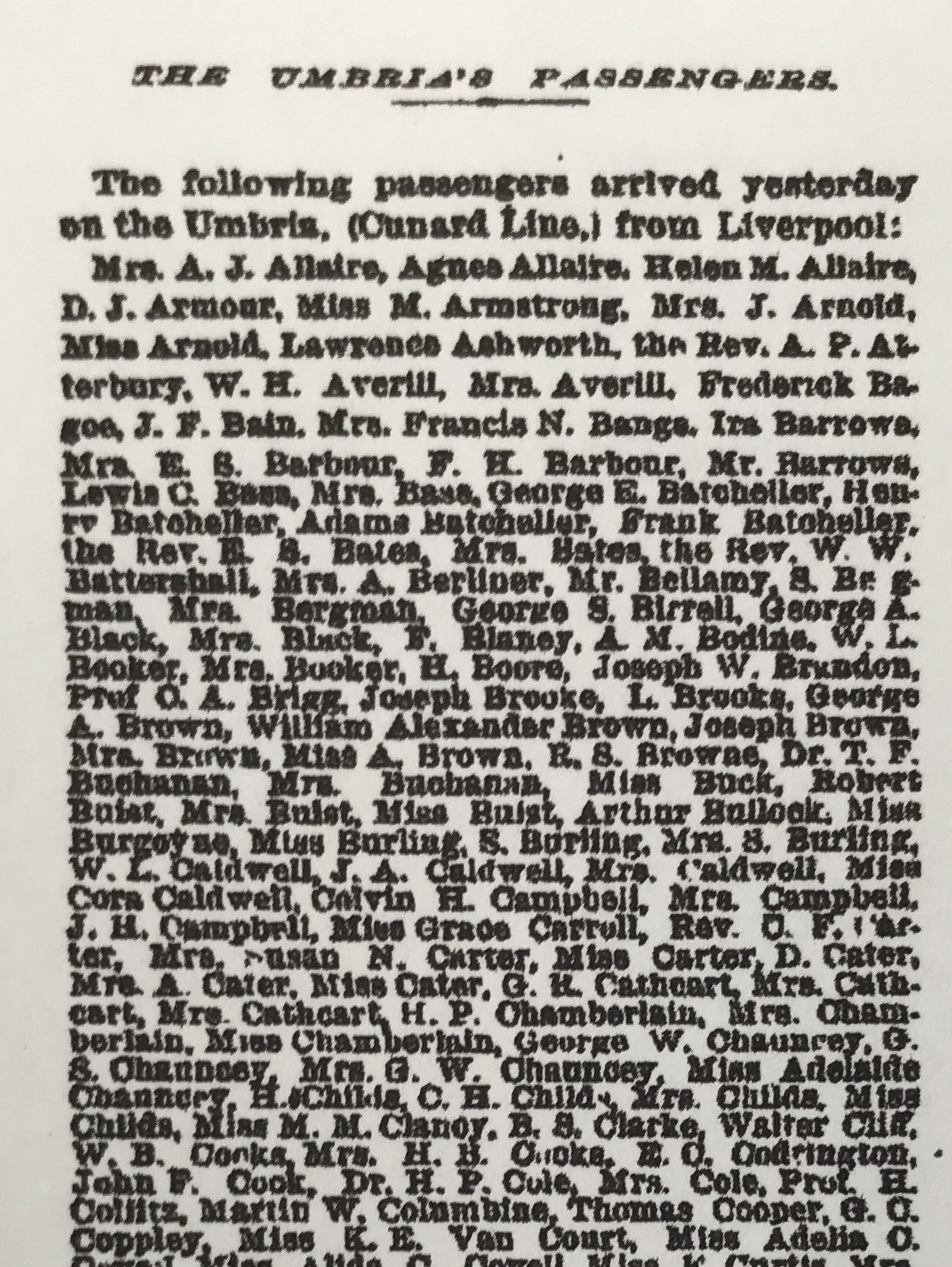

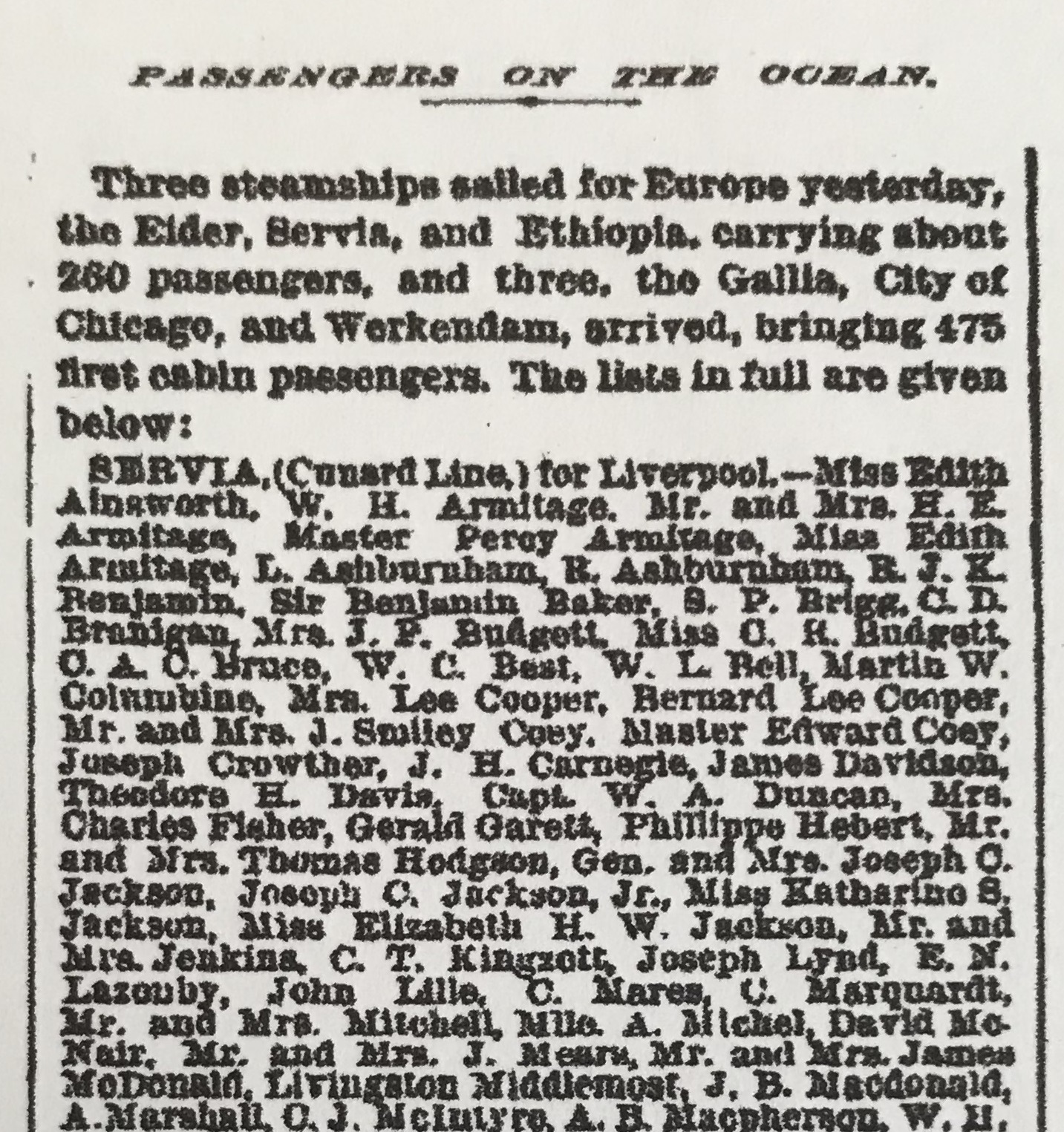

In September 1890 Martin arrived in New York aboard the Umbria (Cunard Line) from Liverpool and two weeks later began his return to the Lancashire port on the Servia (same line). A business trip connected with the exporting (above)? (Karen)

Can you spot him below ?

A long-time sufferer of anaemia, Martin died at his Albert Street home on November 15th 1914, aged 53.

He was buried at Nottingham General Cemetery three days later.

Catherine died on February 19th 1926, aged 67, at the same address.

————————————————————————————————————————————

And finally, a look at the family, all together