… with the Sir John Warren in close proximity on the left.

Saying goodbye to the Marshall family, we now follow Adeline who points out the King’s Head Inn, home to ……

William Woodroffe, landlord, c. late 1830’s to 1866.

There is evidence that the King’s Head was serving ale in 1834 (at least)

Adeline points out the inn to us: “At the corner of the Market Place, and Pimlico, was the King’s Head, landlord Mr. Woodruffe. There were no children. After Mr. Woodruffe’s death, the widow went to live with her sister, Mrs. Lowe, on Stanton Road. Mrs. Derbyshire senior was also her sister”.

Adeline seems to have tangled up the ‘Woodruffe’ details in her description (above).

Mrs Woodroffe was born Maria Nightingale Simpson, daughter of John and Sarah (nee Nightingale), and she married William Woodruffe on October 16th, 1837. It seems that, at least from the time of that marriage, the couple were at the Inn.

Her husband was landlord of the King’s Head throughout the 1840s and 1850s and until about 1866, just before the death of Maria from chronic bronchitis in February 1867, aged 59. (* see the bottom of this page for more information on Maria’s Simpson family). William was then living at 13 Stanton Road, close to his two sisters-in-law, Mary Lowe, widow of Richard, and Sarah Derbyshire, widow of Patrick. Both widows lived at 17 Stanton Road.

On a January late afternoon in 1858 William Woodroffe was walking back from Nottingham, having conducted some business in that city in the morning. He stopped for supper at the King’s Head in Wollaton, home to brothers Thomas and William Burton, washing his meal down with a little ale and a drop of gin and water.

About half past nine in the evening William left the Wollaton house to continue his walk back to Ilkeston and on Trowell Moor was joined by fellow townsmen Patrick Pollard, tinman and brazier, and John Harrison, lacemaker, who were also walking to Ilkeston.

The trio journeyed on to Gallows Inn and were crossing the canal there when an argument seems to have developed.

William accused Patrick of trying to push him off the road, of hitting him with a bludgeon of some kind and of rendering him senseless, while John was egging on Patrick, using very colourful language.

As the alleged assault was taking place a young Stapleford lad, Samuel Richards, was returning home from Ilkeston and saw Patrick strike at William. After a brief conversation the lad hurried to the nearby brickyard of John Wilson and enlisted the help of Charles Beighton, foreman at the brickyard, and labourer William Hallam, both of whom were working there. Together the three found the injured William and he was escorted home to the Market Place in Ilkeston by two of the Good Samaritans.

On their return to Ilkeston, innkeeper William and his two ‘rescuers’ went immediately to confront Patrick at his home in the Lower Market Place, where they found him still with John Harrison and not in the best of moods. He was most uncooperative while lacemaker John threatened to re-arrange young Samuel Richard’s teeth. The confrontation seems to have ended when Police Constable Rouse approached.

When they all appeared at Smalley Assizes a few days later, Patrick and John suggested this was a case of self-defence. Despite the fact that none of the other witnesses agreed with them, the defendants argued that innkeeper William was helplessly drunk and they had taken him ‘in charge’ to prevent him from being robbed. As they approached the town William had become belligerent, struck out at Patrick and threatened to push him into the canal. What else could they do but retaliate?

This testimony did not impress the Bench and Patrick and John were each fined 10s with costs; or in default of paying, six weeks in gaol with hard labour.

Just after this January encounter, William along with his wife Maria, were involved with the ‘law‘ once more. They were at the County Court in Derby, giving evidence in a case which involved a ‘missing tankard’ from the King’s Head.

In the previous October, Maria had noticed that she was missing a metal tankard from the inn, one easily recognisable as it had her husband’s initials on it, along with a number 5. It shortly thereafter reappeared at the beerhouse of John Barker on Ilkeston Common, when his wife Sarah bought it for 4s from William McKnight, a visiting draper of Mount Street in Nottingham. He, in turn, had just bought it from someone for the same price and resold it immediately — not a clever piece of business !!

Suspicious Sarah took it eventually to the town policeman, Sergeant Hudson, and further enquiries identified labourer Alfred Cooper as the original seller of the mug — and landlord William was able to identify him as being in the King’s Head during Wakes Week in October, when the tankard went missing. Alfred initially pleaded innocence — he had bought the jug from a boatman, name unknown, but at the trial thought it wiser to plead guilty. Because of a previous offence he was awarded 3 months in prison with hard labour.

William Woodroffe died in June 1872, aged 62 – that is, after his wife and not before as Adeline suggests –and was buried with Maria in the graveyard extension of St. Mary’s Church.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Landlords post-Woodroffe, 1866 to 1901

Charles Turton was the next landlord of the King’s Head until July 1877 when the licence was transferred to William Slater, formerly of Queen Street beerhouse in Basford. By now the King’s Head was numbered as 5 Market Place.

Charles eventually moved on to the Nag’s Head beerhouse in South Street.

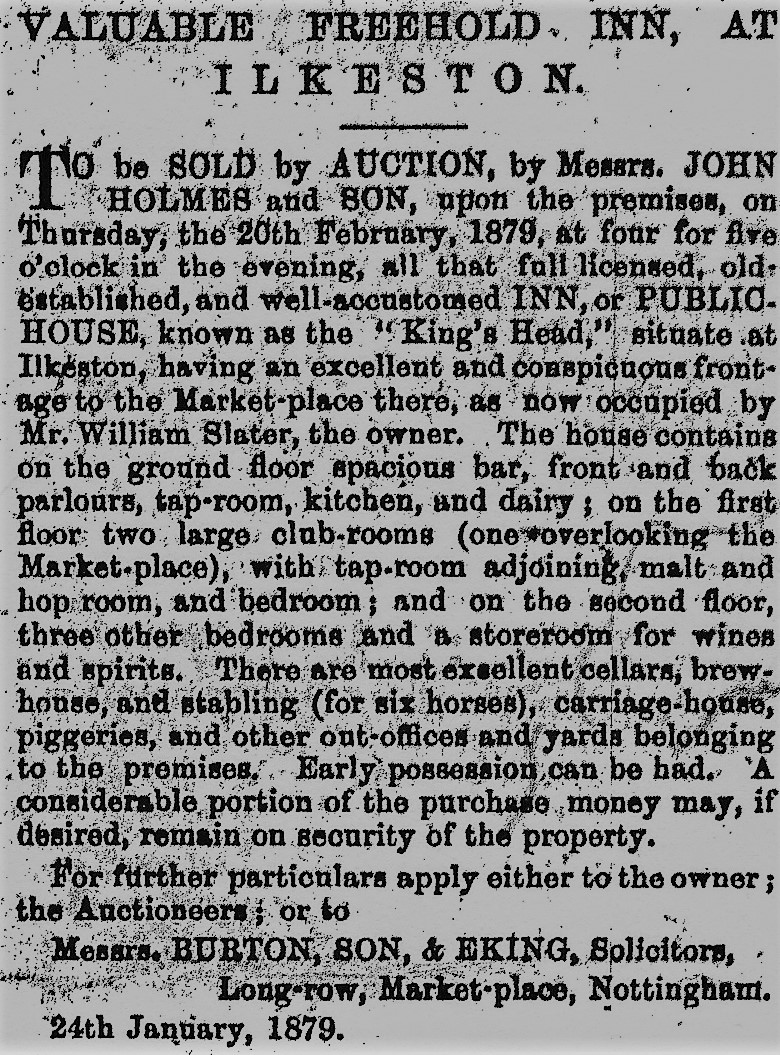

For sale at auction

In January 1879 the Inn, with its ‘excellent and conspicuous frontage to the Market Place’ and still occupied by William Slater, was put up for sale.

On the ground floor it had a spacious bar, front and back parlours, tap-room, kitchen and dairy, with two large club-rooms on the first floor, with tap-room adjoining, malt and hop-room, and bedroom.

On the second floor there were three other bedrooms and a store-room for wines and spirits.

There were also excellent cellars, a brewhouse and stabling for six horses, a carriage-house, piggeries, and other out-offices and yard.

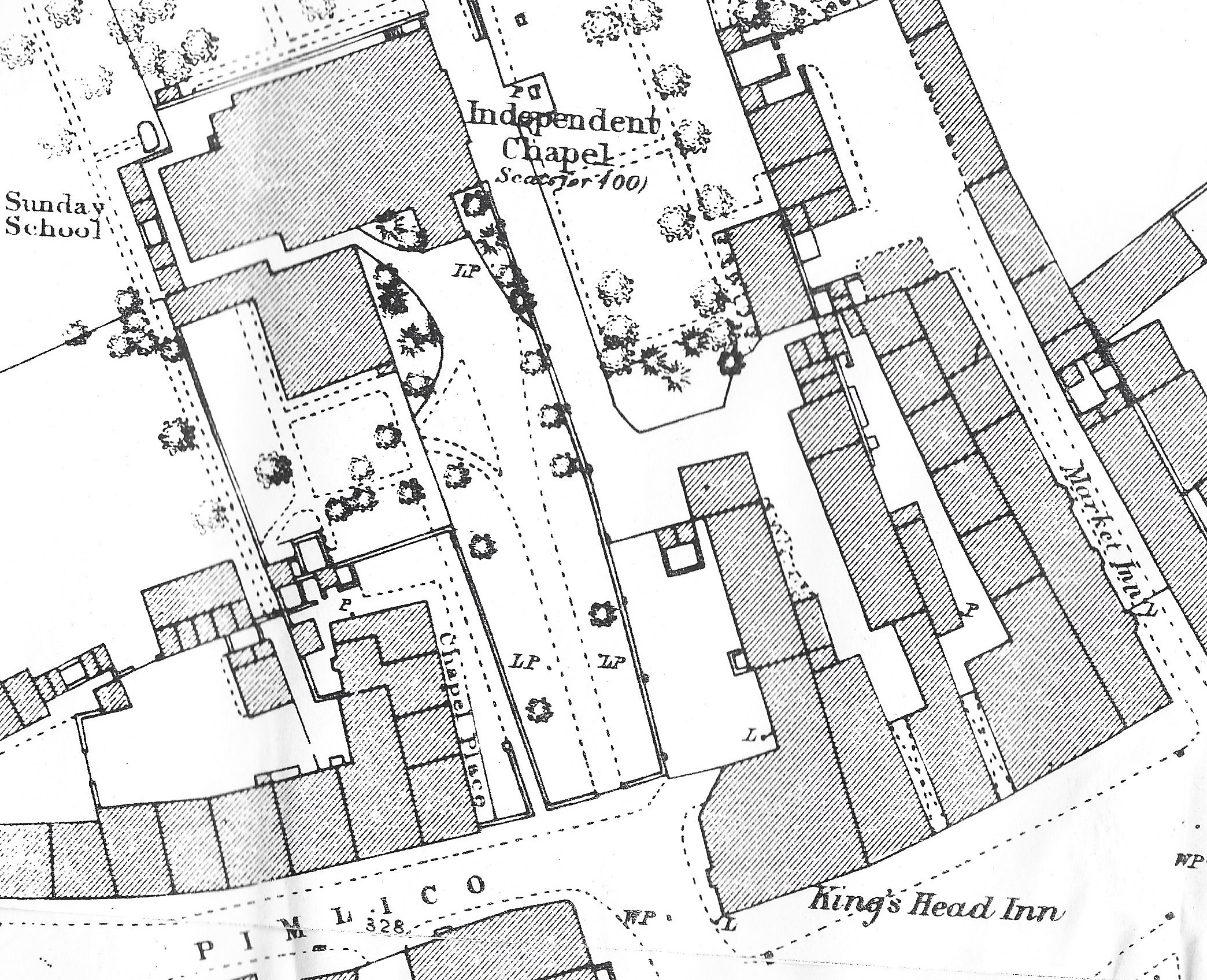

The Inn as it appeared at the time of the auction. …..

You can probably identify its yard, piggery, stables and carriage-house … which leaves the brewhouse ?

Notice that the Independent Chapel could be accessed via a walk through its old burial ground. The lane to its east — later Burns Street — was at that time a dead-end lane

In June 1880 the inn’s licence was transferred from William Slater to Amos Boam, who six years later was almost bankrupt as a result of ‘the great depression in trade’.

Thus in 1887 the licence was again transferred, this time to John Wheatley senior, who was still there approaching Christmas time of 1889 — in time to be fined for selling whiskey unduly under proof. By New Year’s Day John had left, the licence being transferred to his son John Wheatley junior. The latter was married to Alice Ann Attenborough on August 21st 1884, the daughter of Isaac and Sarah (nee Beardsley). Thus, in her short life so far, she had moved from one Market Place Inn to another — just a matter of a few yards apart. John Wheatley junior relinquished the licence (temporarily ?) in March 1895 and then in June (permanently) to William Leivers who was coming from Eastwood.

On December 4th, 1899, at about 5pm, William’s wife, Mary Leivers, went upstairs into her dark bedroom and heard a chinking of bottles. She lit the gas lamp and was amazed to see a pair of legs protruding from under the bed. She called her husband who ran upstairs with a mate (for ‘company’ ?) at which point Thomas Storer pulled the rest of his body from underneath the bed, holding a bottle of whisky. Tommy was a well-known character around the area and had been in the habit of doing odd jobs for landlord William — but this didn’t include nicking his spirits !! He instantly admitted taking the bottle and offered 4s in payment, but William had already mysteriously ‘lost’ ten bottles and so wasn’t in a forgiving mood. The police were called, Tommy was taken into custody, asked for leniency, but was subsequently locked up for 14 days.

William and Mary Leivers were at the King’s Head until the end of the Victorian era.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Woodroffe’s Croft.

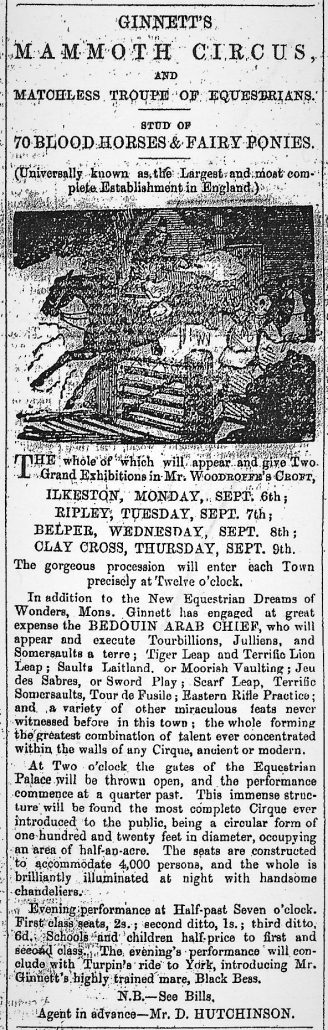

Access to this Croft, a usual site for visiting circuses, could be gained from the rear yard of the King’s Head.

1858 saw the arrival of Monsieur Ginnett’s Mammoth Circus and Matchless Troupe of Equestrians at the field, boasting a circular tent of 120 feet diameter, covering half an acre, lit by handsome chandeliers and seating 4000 spectators.

Prospective members of the audience could look forward to seeing a stud of 70 blood horses and fairy ponies but most importantly, the Bedouin Arab Chief executing Tourbillions, Julliens and Somersaults à terre.

The programme also featured Jeu de Sabres or Sword play, the Tiger Leap and Terrific Lion Leap, Saults Laitland or Moorish Vaulting, the Scarf Leap, Terrific Somersaults, Tours de Fusile, Eastern Rifle Practice, and a variety of other miraculous feats never witnessed before in Ilkeston.

There was an afternoon and evening performance before the troupe moved on to appear at Ripley, Belper and Clay Cross over the next three days.

One can only imagine what some of the town’s folk would make of the arrival of ‘England’s largest and most complete’ Equestrian Wonder as it paraded though the streets at mid-day towards the Croft.

The Pioneer reported that the evening performance was wedged with spectators, leaving hundreds unable to gain admittance.

A few weeks later and the circus was in Derby where disaster nearly struck.

A fire broke out in the attached stables and the flames were moving towards the main tent when the fire brigade arrived. Making use of the readily accessible water, it managed to get the blaze quickly under control such that the people of the county capital were not to be deprived of their equestrian marvel.

The only loss was the dresses kept in the stables.

Writing in 1891 ‘Kensington’ recalled that “you have seen a circus in old Woodruffe’s Close. You’ll not see another. That and the adjoining fields have been laid out for villa residences, and form the Belgravia of Ilkeston, with its St. Mary’s-street (sic) and Jackson-avenue — named it is said, after Stonewall Jackson, who is claimed by some of the former owners as a descendant of the Ilkeston Jacksons”.

I do note that in the early years of the nineteenth century the land lying along what was to later be Burns Street was in the hands of the Marshall family and then by marriage into the hands of the Jackson and Gregory families … strange that later, two parallel Ilkeston streets should bear these names — that is, Jackson Avenue and Gregory Street.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Simpsons

Maria Nightingale Simpson, the wife of William Woodroffe, was a daughter of farmer John and Sarah (nee Nightingale).

The Simpson’s first child was Sarah, born in 1801 but she died in April 1803, when her mother Sarah was pregnent with her second child. The female child was born four months later and called Sarah. She married William Green on October 19th, 1824, and after his death (December 20th, 1828), she married her second husband, Patrick Derbyshire, on New Year’s Day of 1832.

The Simpson’s only son was Job Nightingale Simpson who was born in 1809 but died on October 20th, 1814.

Mary Simpson was the youngest of the family, born about 1813. On January 24th 1834, at St. Peter’s Church in Derby she married Richard Lowe, joiner of Hunger Hill. He was the son of joiner and maltster Christopher and Mary (nee Allen) of Nottingham Road.

Both Sarah and Mary spent much of their lives in Stanton Road … and when both were widows they lived together there.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Round the King’s Head corner and into Pimlico … and there stood the Independent Chapel.