From School Days to ….

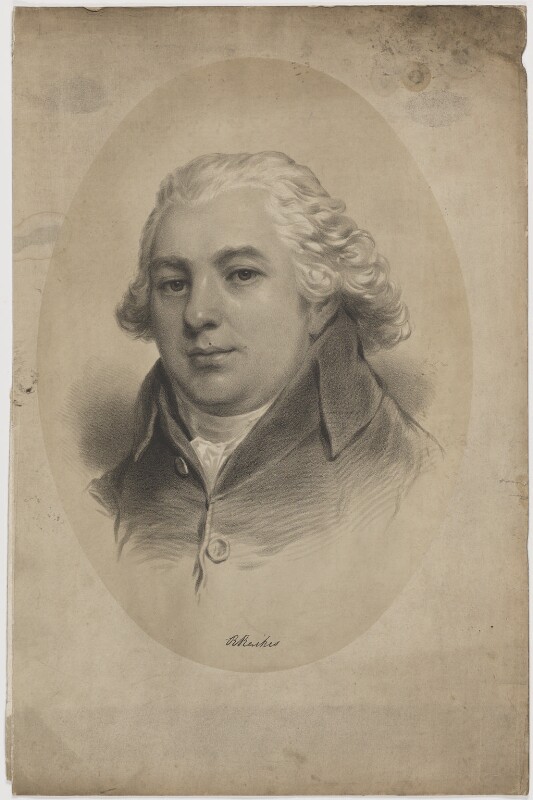

Sunday-schools may date back as far as the sixteenth century but really became popular in the late eighteenth century through the work of Robert Raikes (1735-1811).

He was determined to provide some schooling in his native Gloucester for boys, ‘ignorant, profane, filthy and disorderly in the extreme’, who spent their free time on Sunday creating nuisance and involved in petty crime.

The movement blossomed in the following century, and by 1831 it was estimated that there were 1¼million Sunday School pupils in England.

By the middle of the century about two-thirds of working-class children were attending Sunday-school

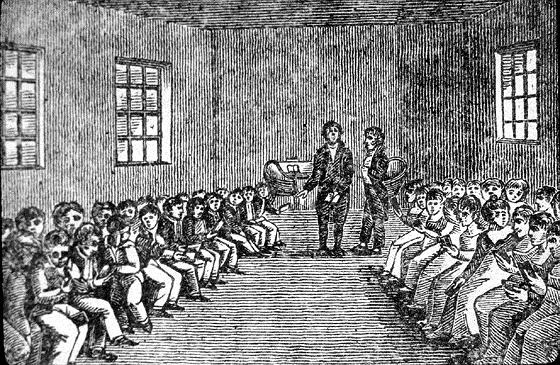

Using lay people and with lessons based on the Bible, teaching at some of these schools may have been poor so that success in teaching the basics of reading and writing was very limited. However attendance was for only a few hours a week and was not compulsory and often not regular.

It should be remembered that on the other six days even very small children were working long hours such that attending their Sunday-school was not a priority on their one day off.

For example, giving evidence to the 1842 Royal Commission on Children in the Mines, seven year old Thomas Straw of Ilkeston — possibly the son of Thomas and Fanny (nee Johnson) — stated that he had worked for about two months at “Messrs Potters Bowswell and Piewit Pits, from six to eight, helping to drive wagons. He feels very tired when he comes out and gets his tea and goes to bed. They would not let him sleep in the pit or stand still. He feels tired and sleepy on Sunday morning and had rather be in bed than at school”.

At that time the Master of St. Mary’s Boys’ Sunday School was Samuel Morris who also gave evidence to the same Royal Commission, having taught at the school for 15 or 16 years.

He had “130 boys on the list who are taught reading in Mrs. Trimmer’s Spelling Book, Part 1, Testament and Bible, also Watt’s Hymns and Church Catechism. They are admitted at four years old and stay as long as they please. They teach from nine to half-past ten. From half-past one until half-past two and three. They attend the services. They have many children that work the pits and he has noticed that they are much more tired than other boys and do not come before 10. They are also much more apt to sleep during the service than others. He thinks children should not go to the pit before nine years old or work more than 12 hours a day”.

A teacher at the same school, William Robinson, was of the opinion that collier boys were “duller and more tired than the other boys. He has often seen even the bigger boys fall to sleep and is sure they are not so quick as the frame-work knitting boys. They have often told him, excepting on a Sunday, they are months without seeing daylight. Another reason is, that being so fatigued they do not attend school hours so well as the other boys. They often tell him they could not awake. He finds them as willing, but far backwarder than the other boys who are not so old”.

(© The Coal Mining Resource Centre, Picks Publishing and Ian Winstanley).

The Independent Chapel in Pimlico also held a Sunday School, its master being shoemaker William Hawley, where the children were taught only reading using the Bible, ‘Burton’s Spelling Book, Easy Lessons and Assembly’s Catechism’.

On Sunday and Monday, August 15th and 16th 1880, the one hundredth anniversary of the institution of Sunday Schools was celebrated throughout Ilkeston. The weather was cloudy to fair, no sunshine but no rain.

On the first day there were numerous Sunday morning meetings at church and chapels throughout the town. These included a teachers’ united prayer meeting at the Wesleyan school-room in South Street and Holy Communion at St. Mary’s Church followed by Divine service there attended by the Salvation Army. The afternoon was given over to children’s services throughout Ilkeston with the parish church being packed by a large congregation plus 700 scholars who had marched through the town from their respective schools to their destination.

There was a more festive mood the following day when many Ilkeston streets had been elaborately decorated from early dawn with flowers and evergreens, and flags and banners were flying from many tradesmen’s windows.

Across Bath Street was stretched a sign with the words ‘Feed my lambs’ in white wool on a scarlet background. Further down the street another arch exhorting ‘Cease to do evil’ and ‘Learn to do well’. At St. Mary’s girls’ school was a gaily decorated maypole around which danced 12 young girls, dressed in white with blue sashes and wreaths of flowers around their heads.

In the afternoon the town’s streets were packed with thousands of eager spectators as Ilkeston Brass Band headed a procession, more than a mile in length, of nearly 3000 children from 14 Sunday-schools, from the Market Place, down Bath Street, along Awsworth and Cotmanhay Roads and thence to the south of the town.

The members of each Sunday school wore different colours … St. Mary’s Church (dark blue), Ebenezer U.M.F.C. (amber), Wesleyan (dark green), Primitive Methodist (cardinal), New Connexion (mauve), General Baptist (dark pink), Independent (violet), Free Church, South Street (crimson), Primitive Methodist, Cotmanhay (primrose), Testament Disciples (light blue), Free Church, Cotmanhay (light pink), Unitarians (light green), Hallam Fields Church (cerise), Kirk Hallam Church (navy blue). The younger children were carried in gaily decorated carts and wagons.

The procession was led off by ‘marshal’ Samuel Richards, grocer of Cotmanhay Road, and the two churchwardens — grocer William Wade and druggist William Fletcher — on horseback. Closely following them was a carriage bearing Thomas Bramley of Heanor Road, aged nearly 103, and a small child, 100 years his junior. (The latter was reported to be the son of Bath Street barber and tailor James Turton and Hannah (nee Fletcher) and would have been Tom Fletcher Turton born in 1876). These two passengers bore deep blue sashes, one with the gold figures ‘1780’ and the other with ‘1880’.

The terminus of the procession was at the Recreation Ground in Pimlico where the children were treated to a free tea and, joined by 4000 spectators, hymns were sung, followed by games and amusements. The promoters of the event seemed to have underestimated the numbers who might be present at this point and this provoked the only ‘sour’ note of the day — they appear to have run out of tea! Otherwise the local press considered it “an unmitigated success, and it has undoubtedly done much towards engendering a kindly feeling amongst the various denominations of the town towards each other…The stereotyped phrase, that it will be a day long to be remembered, was never used with more truth than in this instance; and if appearances are worth anything at all, the effects of this Centenary celebration will not die away for many years to come”.