Scene; Ilkeston in darkness.

The Highway Board had to confront the issue of the town’s lighting.

“A silver watch was lost by the daughter of Mr. Smith, Cotmanhay, on Sunday night last, as she was returning from the Baptist Chapel, and an immediate search for it by candle-light proved fruitless. On the following day the crier announced the loss, and very soon the property was restored to its owner by a youth who had picked it up the previous night”. (IP 1856)

Public Meeting No. 1 (1855)

Public lighting within the town – or lack of it – was a divisive issue which exercised the minds, and voices, of many of Ilkeston’s prominent citizens. As we have seen, as early as 1845 the issue had been discussed, and it arose again in the mid and late 1850’s.

For example, in November 1855 a meeting of the principal ratepayers was convened at the National school-room in the Market Place at which it was agreed that the town’s main streets should be lit throughout the winter months. The gas was on hand and the lamp posts erected, so why not put them to good use? The venture was financed by a liberal public subscription.

But it appears that the ratepayers were not prepared to put their hands in their pockets every year. Thus the ‘experiment’ was short-lived and during the following winter Ilkeston’s main thoroughfares were once more plunged into darkness.

Interlude 1855-1857

As the winter of 1857 approached the Ilkeston News girded its loins and launched a critical editorial attack on the town’s lack of sustained action.

“When a stranger enters our town by night nothing strikes him so much, and gives such an unfavourable opinion of it as the nearly unmitigated darkness. Erebus is the ruler. Go almost where you may, you are surrounded by a black gloom which the few lights which do exist serve to render more dismal by reason of the contrast which they afford. In our principal streets and in the market-place itself the passenger is indebted solely to the gas which illuminates the shops of our tradesmen, and after a certain hour they being extinguished there is nothing at all left to break the darkness except the occasional glimmering of a lamp from over the entrance to a tavern or public house. It is not safe for many, if any, to walk out during an exceedingly dark night…there is great danger of running foul of someone or something, and thus occasioning or causing (or both) an accident. Need we remark how unpleasant and annoying it is for members of the fair sex to sally forth amid such darkness; especially when they are obliged to go through localities which form the gathering-place or rendezvous of not the best characters in the world? In addition we may mention the increased facility which darkness always gives to those who are beset with dishonest propensities and find it more agreeable to obtain a living by theft than by honest sweat of their brows. None have reason to wish the absence of light more than these characters have”.

The editorial went on to state that the street lamps had been lit before, but only after considerable effort on the part on individual townsmen and in the face of difficulty and opposition. But now the lamps stand useless.

It urged the inhabitants to contribute towards the cost of supplying light.

The campaign to supply street lighting was also supported by the Pioneer. It was appalled that a town of 8000 inhabitants could not agree to pay £50 or £60 a year for this.

“A shilling per house or three-half-pence per head per annum too high a tax for the advantages of light!”

Public Meeting No. 2 (1857)

In December 1857 the powerful Churchwardens of Ilkeston were William Riley and Samuel Potter. They had been petitioned by prominent tradesmen of the town to raise the matter of Ilkeston’ public lighting, and determine whether the ratepayers of the parish wanted the streets to be lit by gas and were prepared to pay for the ‘privilege’ — as was their right, set out by the Lighting and Watching Act of 1833.

The ‘prominent tradesmen’ who signed the petition were John Beardsley, Thomas Merry, William Ball, Alfred Sudbury, Isaac Warner, Joseph Carrier, George Blake Norman, John Gibson Eggleston**, Samuel Carrier, Richards Smith Potts, George Small West, William Carrier, John Taylor and Ralph Coulson.

** The only ‘stranger’ on the list is John Gibson Eggleston, a confectioner who for a very short time in the mid-1850s, had a shop in the Market Place.

Consequently a Public Meeting of Ratepayers who lived within the parish boundary was organised. It was to take place at the Boys’ National School Room on Monday, December 14th, at 6 o’clock in the evening.

The area of the town to be considered was extensive, and was described in a notice which appeared in the Ilkeston Pioneer (eg. December 10th 1857). To illustrate the area I have used this map found in Trueman and Marston (which was revised and corrected from a map published in 1886). Remember that many of the streets and features shown in the map were not laid out in 1857 or were known by other names.

The boundary of the area started at Matthew Hobson’s Cow Sheds on Nottingham Road (close to Field House which had just been built for the Hobson family). (1)

It then crossed over this road and followed a path to Millfield Lane (now Park Road) (2) and then down to the Erewash Canal Bridge and Potter’s Lock, near to ‘Mr. Samuel Potter’s House (known as the Park). (3)

It then followed the line of the Erewash Canal up to the Ilkeston Town Branch Line of the Erewash Valley Railway. (4)

At that point it crossed that rail track and then followed it up to a path which led towards the Bridge Inn. (5)

That path took it to Bullock’s Hedge Nook near Ebenezer Chapel. (6)

From the chapel the route crossed the Cotmanhay Road, up Charlotte Street (then known as Cross Lane), and on to Heanor Road. (7)

It crossed that road and followed the parish boundary line of Ilkeston and Shipley to the Nutbook Canal. (8)

Southwards, it followed the canal to the West Hallam Road (Derby Road). (9)

Following that road, it went up to a new street, newly laid out and known as Belper Street, near the Three Horse Shoes. (10)

Along Belper Street to Little Hallam Lane which was crossed (11) and finally back to Hobson’s Cow Sheds. (1)

Imagine taking a walk around Ilkeston and following the numbers in sequence: everything on your left would be included in the ‘lighted area’. You might note that large sections of the town (eg. almost the whole of Cotmanhay) were excluded — this was because they were ‘unimportant’, contained few ratepayers, or had not been sufficiently developed by the mid-1850s.

At the advertised meeting to discuss the issue, various resolutions were put forward in an effort to light the town but all were voted down by the majority of ratepayers. Some of their objections might sound familiar even today.

For example, one farmer, dressed in ‘his best coat and worst manners’, did not see why he should pay for lighting when he would not benefit from it nor make any use of it. He had no daughters who could suffer from rude remarks or ruder assaults by the louts who frequent the dark, narrow streets; he had no sons to take advantage of those same black streets and commit nuisances; and his chickens and pigs had no need of light!

The Pioneer despaired. “Is this Ilkeston? – IMPROVING Ilkeston?” it cried.

And a disappointed Ilkeston News reported that ….

“thus ended another of those scenes so often enacted at Ilkeston of late in the struggle for light against darkness. It is to be regretted that the working men of Ilkeston, generally so quick to detect any thing oppressive or to check their bent or discomfort, should make such a determined stand against the lighting of the town, when it would be more to their comfort than to any other class, for they have to go to and from work thro’ the dark muddy streets in the cheerless winter’s night, when for about the sum of SIXPENCE each they might be greeted with the blaze of the lamps; and to their families it would also be a boon, for who loves light more than children? And who needs it more than women?”

In November 1858 an agreement was reached with the Directors of the Gas Company to light the town‘s street lamps, from the beginning of December to the end of March. The cost was to be paid by subscriptions, although the Gas Company did agree to light the double lamp in the Market Place for free on Saturday evenings !!

This seems to have continued for some time, with the cost being defrayed by private subscriptions from parties who lived in the vicinity of the lamps.

Public Meeting No. 3 (1862)

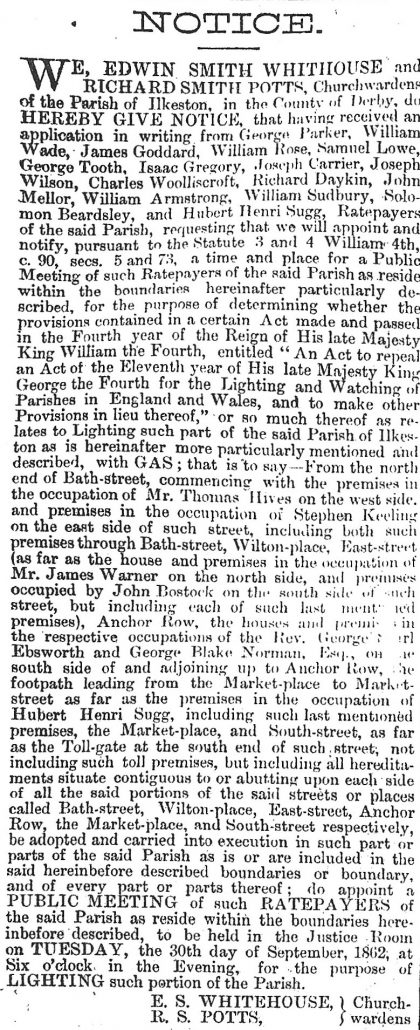

In September 1862 the churchwardens Edwin Smith Whitehouse and Richard Smith Potts gave notice of another public meeting of Ilkeston’s ratepayers to determine whether gas lighting should be provided for parts of the town.

The parts to be lighted were described as ……

from the north end of Bath Street, commencing with and including the premises of innkeeper Thomas Hives (the Rutland Hotel) on the west side and the premises of grocer Stephen Keeling on the east side (in Granby Street);

then southwards along Bath Street, taking in Wilton Place and East Street as far as and including the premises of beerhouse keeper James Warner on the north side and cooper John Bostock on the south side;

Anchor Row, Dalby House and the Vicarage;

the footpath from the Market Place to Market Street up to and including the premises of Hubert Henri Sugg (later the Anchor Inn);

the Market Place and down South Street up to but not including the Toll Gate at its south end.

Basically this meant lighting Ilkeston, from the Rutland Hotel at the bottom of Bath Street up to the Market Place and then down South Street almost up to its end. Illuminated Ilkeston would also include several streets off these main thoroughfares, as mentioned above, and of course, include Dalby House and the Vicar’s home.

Notice that this was a much restricted area when compared with the one suggested in the previous Public Meeting of 1857.

It took two ratepayer meetings to come to a decision. Hubert Henri Sugg — who had a vested interest in the decision (see the lighting areas above) — had done the Maths and at the first meeting reckoned a rate of 5d or 6d in the £ was enough to cover the total expense. It was agreed that it couldn’t be accomplished on a voluntary basis and so a compulsory rate was the order of the day. At last and at this time the ratepayers had decided to light the town, or at least part of it !

Thereafter, from mid-October to mid-March, some of the town’s main thoroughfares were lit with artificial light.

————————————————————————————————————————–

This was just prior to the Local Board’s formation.