After Dalby House and Dr. Norman Adeline leads us to the corner of High Street with Anchor Row: “we pass the old Unitarian Chapel, one of the oldest, if not the very oldest in the town —I believe it was a Presbyterian Church prior to being a Unitarian. It had large box pews, and it was in one of these that Miss Walls lived, when she had to leave her tiny cottage in Burr Lane, where she kept a small school.”

The site of the chapel today, 2020

Origins of the Venerable Old Structure … about 1690-1819

On Sunday, April 9th 1922 a service was held at the Unitarian Chapel in Ilkeston to celebrate the 230th anniversary of that chapel and to remember ‘those who long ago built the original venerable house’.

The sentiments of the ‘not large’ congregation were reflected in the words of their hymn….

We love the venerable house, Our fathers built to God,

In heaven are kept their grateful vows, Their dust endears the sod.

Here holy thoughts a light have shed, From many a radiant face,

And prayers of tender hope have spread, A perfume through the place.

Evidence would suggest that the original ‘venerable house’ was not a purpose-built place of worship but rather a domestic dwelling, registered as a place of worship.

Adeline makes mention of a ‘Presbyterian Church’ and there is reference to ‘a little Presbyterian community which had met in Hannah Carrier’s thatched cottage’ in 1692. This followed the Act of Toleration of 1689 when, on January 10th 1693 this cottage was registered as a Presbyterian meeting house.

(At this time and later, the term ‘Presbyterian’ often simply referred to Nonconformists, and as time passed some Presbyterians became ‘Protestant Dissenters’ who later became ‘Unitarians’)

In 1718 the first chapel was built at Ilkeston (Trueman and Marston).

According to Edgar Waterhouse, at Ilkeston’s Manor Court in that year, William Richards and his wife, Miriam (nee Carrier, the widow of Michael Baguley), with Hannah Carrier (the sister of Miriam ?) gave up 14 yards of a garden at the corner of Gipsy Lane (later known as Anchor Row) and another lane (later High Street) to eight people ‘for the purposes of erecting a Chappell or Meeting house for a Society, Congregation, or Assembly of Presbyterian Dissenters from the Church of England’. And in the year 1718/19 it appears that the premises were registered as a Place of Worship.

Frank Burrows, a Bath Street bookseller and stationer, contributed a series of articles to the Ilkeston Pioneer in 1907, which contained an account of the history of the High Street Chapel and its ministers….

“So far as is known, no print or photograph of the venerable old structure exists. It must have been a quaint little place. It ran north and south, and had a roughly made gallery at one end”. The stairs up to this gallery were “very creaky and not at all strong, and a false step might have meant a break down. The entrance was from a small graveyard on the west side. The pews were of the old fashioned high-backed type, suggestive of sleepiness. Over the fine oak pulpit was a carved sounding board. The singing was supported by instrumental music, violins, ’cello, flute and double bass. …. The ceiling was supported on roughly trimmed timber, and the chapel was white-washed. A triple lancet window faced Dalby House”.

Edgar Waterhouse identifies the early pastors as John Platts who died in 1735; ?; Mr. Williams 1750-1785; Mr Davis senior and junior, until 1787; Mr Owen til 1791; Mr Hughes and Mr. Walters until 1807; and notes that they were “nearly all Welsh names”

Chapel squabbles …. 1819-1860’s

For most of the first half of the nineteenth century the Rev. Mark Whitehouse was minister at the church (1819-1856).

“He was a man who loved a country life, and in appearance was more of a farmer than a minister. Clad in blue smock, and wearing on his head a white hat with a black band on it, he rode regularly into the town on alternate Sundays”. (Frank Burrows).

It was Mark who supplied the statistics for the national Religious Census of 1851 which showed a Sunday afternoon congregation at the chapel of about 10 to 12 persons in total. The total accommodation was 100 free places.

Mark’s death in 1856 led to the closure of the chapel until 1859, when the Rev. Thomas Read Elliott arrived for a two-year stay.

Mark’s death also led to an unsavoury dispute among some members of the chapel’s community.

The chapel keys were retained by the caretaker, William Mellor, who now regarded himself as its new owner and he took it upon himself to secure the building with a large padlock.

His claim to ownership rested upon the fact that he and his ancestors had for many a year cleaned and taken care of the place!!

Needless to say the would-be worshippers at the chapel were a little peeved and had to break into the building with the help of George Small, the parish constable.

A legal tug-of-war ensued, with claim and counter-claim, but the magistrates refused to interfere. They did however suggest that Mr. Mellor should return the bible, hymnbooks, cushion and clock which it was claimed he had removed from the chapel.

It seems that this argument caused some discussion in parts of the town and led to William Mellor’s sister, Elizabeth, appearing at Smalley Petty Sessions, accused of assaulting Thomas Worcester Barker, lacemaker and house agent of Albion Place. She had taken exception to ‘lies’ that Thomas was spreading about her brother and had been provoked to attack him.

“The Magistrates, not being able to see that the alleged provocation entitled her to plough furrows in Barker’s face or to bleed his nasal protuberance, directed the payment of 24s for the scratch which was immediately paid” (IP)

If he did have the chapel bible, it’s possible that William Mellor did not return it. An illuminated inscription records that ‘the present bible was presented by William Enfield, of Nottingham, to the worshippers of the One True God assembling in the Unitarian Chapel, Ilkeston, November, 1856.’ (Frank Burrows)

A new chapel 1867-1869

The old chapel was taken down in 1867. “The chapel was originally attended by the leading families of the town and district” but numbers had much declined up to the 1860’s.

When the foundations were removed the local newspapers reported that this revealed the much-decayed bones of an adult person, though no-one could recall anyone ever being buried inside the chapel. On one of the pillars supporting the gallery were the figures 1719, supposedly the date when the gallery was erected and not when the chapel was built.

The Rev. William Shakspeare had arrived in Ilkeston from Crich in 1862 and under him a new, larger Unitarian chapel, designed by William Warner, was erected and opened on October 14th, 1869 over the site of the old one. The small graveyard there was lost along with tombstones, the human remains being transferred to St. Mary’s graveyard.

“No care seems to have been taken to preserve a record of the inscriptions on the tombstones”.

“The old oak pulpit and pews, the old minute books, the list of subscribers, the old pulpit Bible, all are gone. Where? Not even a sketch or plan of the old chapel remains. There is no trace of any communion plate. Fortunately, one of the early registers, containing entries of births and baptisms from 1735 to 1820, was sent up to the Registrar General, on the passing of the Registration Act in 1836, and is in safe custody at Somerset House”. (Frank Burrows)

This register is now kept at the National Archives though a copy is held at Derbyshire’s Record Office in Matlock.

While the new Unitarian chapel was being built (1868-1870) the congregation used the Old Cricket Ground Chapel which had once served as a Wesleyan Methodist chapel but was then being used by William Warner as a wood workshop. The new chapel eventually opened for public service in 1870. According to the Ilkeston Telegraph of September 1873, the funeral service of John Swanwick of Springfield Terrace, son of lace manufacturer George, was the first ever held in the New Meeting House.

The Shakspeares

The Rev. William Shakspeare’s wife, Anne (nee Attenborough) was the daughter of Joseph and Ann (nee Buckland) of Gilt Briggs Farm, Kimberley. She was the chapel organist and with her husband ran a night school at the chapel for a good number of years. Their eldest son, also called William, eventually replaced his mother at the chapel organ when old enough, and helped his parents at the night school, well into the 1870‘s — until a series of Education Acts changed the nature of elementary education in England and ultimately did away with the need for evening schools.

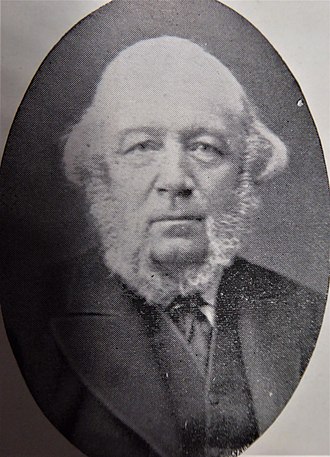

William senior served as minister from February 1862 until his retirement in 1887. He died, aged 78, on August 14th 1909 at Stratford House, the family home in Market Street. His widow Ann continued living there until her death, October 11th 1914, aged 82.

William junior was on the staff of the newly-formed Ilkeston Advertiser in 1881and later was its editor and proprietor.

Brother of William senior was James Shakspeare who took over the printing and publishing of the Ilkeston Telegraph in the spring of 1870 while the previous proprietor, Frederic Lomas, left for ’Bank Chambers’ in the Market Place, Nottingham.

And within months the brothers Shakspeare were embroiled in a libel case with arch rival John Wombell.

Handbills had been posted and circulated around town, headed ‘Notice Zachary’ and suggesting improper conduct between the editor of the Pioneer and a young lady who had spent a short stay in the Wombell household — not the first time that John had been accused of impropriety!!

John vehemently denied the accusations and proved that the printing presses of the Shakspeares had been used to produce the offending material.

In March 1871 the libel case moved from the Petty Sessions to the Spring Assizes at Derby where John believed ‘a verdict against the Shakspeares was certain and that it would be ruinous to the defendants, particularly the preacher’. He had no wish to see either of them in prison and nor did he seek damages. Thus he accepted their apology in court plus £25 towards his costs. No evidence was subsequently offered and the brothers were discharged, a verdict of ‘not guilty’ being recorded. (March 7th 1871)

The Rev. William’s eldest son, also named William, was born on December 7th, 1858, at Belper, but by about 1861 was living with his family in Belper Street, Ilkeston.

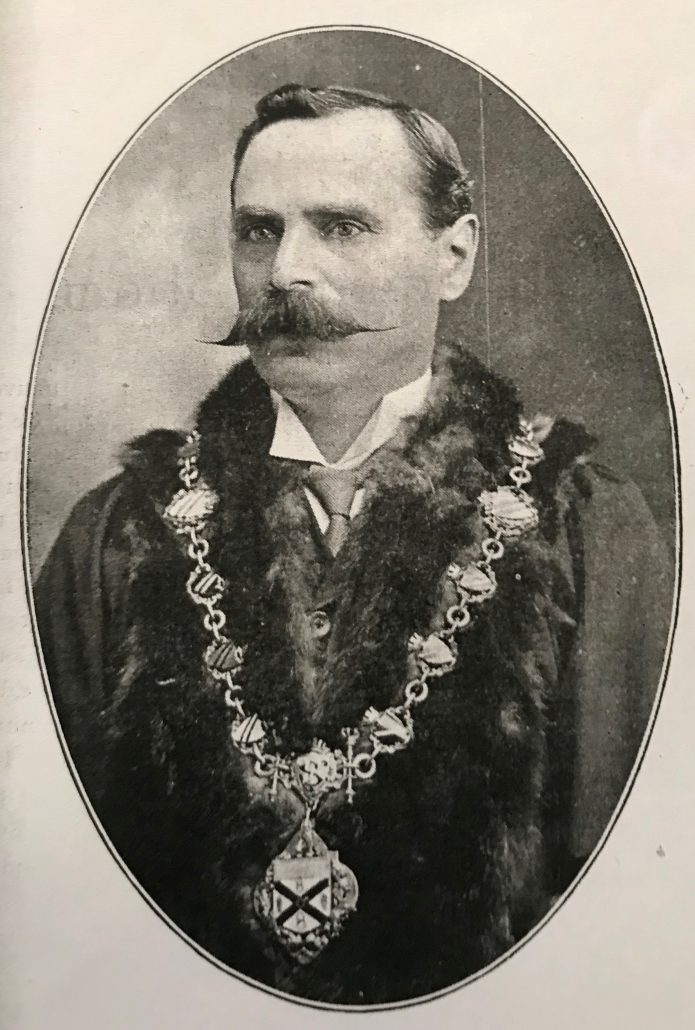

He played a distinguished role in the civic affairs of the town. … a member of the Town Council from 1902, until he retired, and Mayor in 1908-9. (see him, left, in his finery)

A Liberal in politics and Non-conformist in religion, he was a member of the Ilkeston Liberal Association and the Congregational Church in Wharncliffe Road.

William succeeded William Merry as Registrar of Marriages when the latter died on December 30th 1906.

His first wife, whom he married at the Independent Chapel in 1888, was Sarah Emily Roe, the daughter of Ilkeston printer Thomas and Hannah (Ford). Their daughter, Sarah Emily Marguerite, was born in 1889 but just six days later the mother was dead.

William remarried in 1893 to Edith Hannah, the daughter of Inland Revenue Office, Thomas Bradley Lister and Sarah (nee Dorricott), They had three daughters, the eldest — Dorothy Alice — later becoming editor of the Ilkeston Advertiser.

William died on July 6th 1939, aged 80, at the family home of Avon House in Heanor Road … later home of the Ilkeston Advertiser.

In 1893 the chapel was registered for marriages. In March of that year the first wedding to be solemnised there was between coalminer and widower Moses Straw and Mary Jane Fisher, ‘the nuptial knot being tied by Mr. G.D. Hughes of Nottingham High Pavement Church, in the presence of numerous friends’.

In commemoration of the event the newly wed couple were presented with a Bible.

“Mr. Hughes remarked that while they did not regard every word of the Bible as the infallible word of God, they believed it to be the grandest of books, and the one by which they should regulate their lives”. (IA)

Born in 1868 Moses was the first of the several illegitimate children of Charlotte Straw and her second cousin, coalminer Thomas Straw. The couple later married in 1878.

Moses and Mary Jane regulated their lives together at 34 Wood Street for nigh on 50 years.

The chapel ceased to be used by the Unitarians in 1960, since which it has served as a printer’s shop and as the Kingdom Hall of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. After this it was converted into a Masonic Lodge.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Post script ……. Below is the article which appeared in the Ilkeston Pioneer, May 27th 1955, concerning the pamphlet written by Frank Burrows and the earler Pioneer articles. These can also be found in the newspaper of April and May 1907

Post post-script

Before we leave the Shakspeares, let’s have a mention for Fanny, born in 1871, the daughter of William senior and Ann. In 1891 she was a scholarship student at the training college for School Mistresses at Saffron Waldon; in that year’s examinations she gained second place in college, an institution which drew students from all parts of the country. She went on to marry schoolmaster Harry James Carter at the Unitarian Chapel on July 28th, 1897. The couple then settled in Jersey where they both initially taught at the Wesleyan School in St. Ouen parish.

————————————————————————————————————————-

Ilkeston’s Nonconformist Council: October 1895

On October 23rd, 1895 the public inaugeration of this Council took place at the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Bath Street. The aim was to bring together the hitherto divided and various Dissenting bodies of the town, with a view to united action on matters affecting Nonconformity, in the face of “sacerdotal aggressiveness“. Its president was Thomas Roe (printer, stationer and publisher of the Ilkeston Advertiser), with the Revs. James Herbert Bainton (Congregational Chapel) and George Dean Jeffcoat (Baptist Chapel) as secretaries.

Thomas reminded the meeting that Nonconformity’s origins were based in dissent from the teaching and organisation imposed by the Established Church and its privileged status. Everyone had a right to free worship and their new Council was formed to help pursue that aim; “Every man to his duty, and God for us all”. The Puritan tradition of which they were descendants taught them to resist in every way the sectarianism of the country’s education and any limit on the nation’s religious freedom.

The main speaker at the inaugeration was John Carvell Williams, the Liberal M.P. for Mansfield and Nonconformist campaigner. John stressed the need for self-government within Christian churches, not have their affairs managed by the Govenment of the country. Jesus was the only head of their churches, not earthly sovereigns, and they should be supported by voluntary means only. Because of these principles, they were opposed to the existence of a national establishment of religion. He alluded to the appointment of bishops by the Prime Minister, the powerlessness of the Church laity, to the scandalous sales of the rights to present to Church livings, as points on which reform was being sought.

John went on to discuss the opposition demonstrated by the Church of England to the formation of School Boards; and when this opposition failed, the Church’s attempts to ‘neuter’ the Boards by packing them with Churchmen — in this way they could manage the Boards such that they could have no injurious effects on the Church schools. Churchmen were looking after the interests of their Church rather than the interests of education.

The meeting concluded with all the churchs represented there affirming their determination to work together, no matter what their differences — unity in diversity.

————————————————————————————————————————-

And so we come to Anchor Row.

The entrance to Anchor Row from High Street. Out of view, on the left, is Dalby House, home to Erewash Museum.