West’s drapery.

Adeline points out that “next door to the Market Tavern was Mrs. West’s drapery establishment. She was a widow. This family were Baptists”.

The premises had long accommodated a draper’s business, and at the outset of the Victorian era it was the turn of the West family to trade there.

Mrs. West was born Hannah Twells, daughter of William and Catherine (nee Wallis?) and was baptised and received into the Baptist Church at the age of 15.

By February 1831 she was a widow when her husband, draper William Barnes West – whom she had married in February 1805 – died. Until his death William had been in partnership with draper Peter Preston at this site…. Preston & West, drapers and tailors (Pigots Directory of 1829). After her husband’s death Hannah took his place in the partnership but not for long — in January 1834 the partners announced an end to their agreement. At that time the partners were Hannah, Peter Preston of Sneinton, Nottingham, Hannah’s eldest child, William Twells West of Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, Job Preston (Peter’s son ?) also of Melton Mowbray, and Thomas Anderson of the same place, all in the firm of “Preston and West, mercers, drapers and tailors”.

All the West family were members of the Baptist Church in which they played a significant and active role.

“Mrs West was assisted in her business by her two sons, John and Charles (?), and her daughter, who had married a Mr. Finch”.

The Draper’s shop (Philip V Allingham)

Assisting in Hannah’s business were children Mary, George Small (not Charles), Martha and John.

— Mary West married clay merchant William Finch in 1859 and for a time lived in South Street.

When Mary died in 1876 I believe that her sister Martha married William in the following year.

And in the following year William died, aged 75.

Martha died in Basford in 1893, aged 76, where she had been living with her brother John, until his death the year before – by which time she was twice widowed.

— George Small West, born in Ilkeston, was baptised and admitted into the General Baptist Church at the age of 18 and continued to support that church for the rest of his life.

He was a deacon, leader of the choir and an active officer in the church’s schools.

He also led the Ilkeston Choral Society, was an accomplished violinist, a teacher of music and took a prominent part in many local concerts.

When George died at Sawley in May 1862, aged 48, a funeral service was held at the Queen Street Baptist chapel to remember his services and honour his memory; “his good, kindly, and Christian feeling to all classes of society, will long endear his memory to all who enjoyed his friendship or acquaintance”. (IP)

He was buried at Nottingham General Cemetery.

— As you might see from the adverts (above) younger brother John West worked for a time with George in the Market Place shop until both retired from their drapery business and sold off their stock in mid-1861.

John moved to Basford, married widow Martha Swain there in 1872, and worked as a ticket writer.

He died there in 1892, aged 70.

There were other children, not mentioned here by Adeline.

— The oldest child was William Twells West, born in 1805.

Gap alert!! What became of him?

— Daughter Betty West married butcher James Piggin in April 1850 and went to live in his home town of Hucknall Torkard.

— Ann West. (See Butcher Twells’ shop and field)

— Henry Hale West, colliery agent, married Elizabeth Whitwell in 1850, lived for a time in Shipley and died in retirement at Heanor in May 1886, aged 58.

The mother of them all, Hannah, died in May 1861, aged 79, still living in the Market Place and having been in the Baptist Church for over 60 years.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

William Smith, draper

Shortly after the death of Hannah West in 1861, into the draper’s premises stepped — newly-arrived to Ilkeston — William Smith and his ‘general drapery’.

The draper’s store (left) next to the Wigley’s premises (with the lowered awning) in the 1870s

Brentford-born draper and mercer William Smith arrived in Ilkeston from Nottingham with his wife Betsy (nee Harding) and children about 1862 and set up his establishment in the Market Place.

In February 1871 he was on the platform at the Town Hall, alongside Unitarian minister William Shakspeare, Baptist minister John Stevenson and Independent minister John Bonser, at a meeting chaired by Matthew Hobson, to listen to the Rev. W. Galloway of Birmingham speak on the Disestablishment of the English Church.

The Nottinghamshire Guardian noted that the attendance being ‘very meagre’ it could safely assert that ‘the Liberationists are not very strong in Ilkeston’.

William was a long-standing and outspoken, though not continuous, member of the Local Board up to its dissolution in 1887.

In January 1876 he resigned from the Local Board for health reasons, vowing that he would not in future take any active part in the general business of the town…. a resolution that was destined to be broken before the end of the year.

In April 1877 his health must have improved as he stood for election to the Local Board and narrowly missed being successful — by five votes. It was almost – but not quite – a dead heat, like the one that was seen in the University Boat Race a couple of weeks before.

Illustrated London News 1877

However, whatever disappointment William might have felt at his defeat, it was to be short-lived. In May Mr. Lowe resigned from the Board and the draper was invited to take his place – an invitation that he readily accepted – despite his vow of 1876.

In April 1880 William renamed his premises at 7 Market Place. Now it was to be known as ‘Market House’. (by 1891 — with the renumbering of this side of Market Place — it now appears to have been number 10).

Late on Thursday evening, February 23rd 1888, the news may have circulated in some parts of Ilkeston society of the unexpected death of Bath Street grocer Isaac Gregory. (See A row of three shops).

However this might not have been of significance to draper William who had suffered several years of ill health and, recently returning from a trip to London, had been ‘prostrated by paralysis’. A short return to normalcy was to prove a false dawn. William died that same Thursday evening.

Four days later and preceded by a large contingent from the Salvation Army, William’s hearse was led from the Baptist Chapel to Ilkeston General Cemetery where he was buried.

William Smith and Early Closing.

At his death the Pioneer described William thus:

‘He was an impassioned speaker, and, as a Radical, frequently spoke at political meetings. He was also during the greater part of his life a local preacher in connection with the Baptist persuasion (not surprising as his father was a Baptist minister) and had for many years been a prominent member at the Queen-street chapel. Quite recently Mr. Smith was elected president of the newly-formed Early Closing Association, and only a fortnight before his death he was present as a delegate at a meeting of the Association in London’.

The Early Closing Association had been formed in 1842 to regulate working hours in retail shops and abolish Sunday trading.

It appears that William had long championed some privileges for workers. In December 1866 he wrote to the Ilkeston Pioneer suggesting that, in this year, as there was only one day between Sunday and Christmas Day (which fell on Tuesday), the intervening Monday should be added to the holiday period. The drapers and clothiers of Ilkeston — of which, of course, he was one — were intending to follow his suggestion; he asked other shopkeepers to follow their example. ‘It would be good for all that all should have three days’ holiday’.

Writing in 1880 William recalled that when he arrived in Ilkeston the drapers of the town had ‘a most wholesome law’. For six months of the year they closed their shops at seven o’clock, the other six months they closed at eight o’clock, and on Fridays at six o’clock.

Then, in October 1874, many linen and woollen drapers of Ilkeston agreed to early closing of their shops, at least until March of 1875. Thus, on Mondays they would shut at half past seven; on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, at seven; on Fridays at six. All in order to allow their assistants a little more time for relaxation during the winter evenings, and for which thoughtfulness they hoped their customers would reward them.

“They earnestly invite the public to patronise only such tradesmen as adopt the principle”.

The Pioneer questioned this ‘impertinence’ and wondered why they couldn’t close at ten or half past ten on Saturday evenings.

“If the gentlemen who have agreed to the movement will carry it out in good faith by closing promptly at the time stated, and avoiding all ‘back-door’, ‘side-door’, and ‘through-the-other-shop’ business, early closing will become general, and obtain the acquiescence and approval of the public”.

By 1880 the agreement amongst Ilkeston’s drapers seems to have been forgotten. Their shops were open at all hours, even on bank holidays, and William Smith knew where the blame for this lay. It was the ultra-competitive younger tradesmen of the town, so keen for financial gain, who had broken the good old rule; other drapers had to follow them in order to compete. William longed for the good old days and urged shop assistants to agitate.

“Form yourselves into an association for the purpose… Get up public meetings, get the ministers of the gospel to help you, get the ladies on your side: it is your question, and you must put your energies into it; if anything is to be done. Ventilate the question in every imaginable way, and you will succeed”. (IP May 1880)

In 1888 Sir John Lubbock, MP for London University, introduced a bill in Parliament calling for shops to close at 8pm, and 10pm on Saturdays. It was rejected in the Commons.

Seventeen years earlier he had successfully sponsored the Bank Holiday Act establishing the first such holidays in the United Kingdom.

After William’s death in 1888 the drapery was inherited by his youngest son, Albert Ernest (born in 1865). However, at the end of September 1892 the ‘Market House’ drapery was put up for auction. I think that, for a short time, it was occupied by Messrs Baumfield & Co, tailors and outfitters, before once more being put up for auction in September 1894.

Son-in-law Joseph Hollis

One daughter of William and Elizabeth was Elizabeth Smith junior, born in 1862 at the family shop in Market Place. At the Queen Street Baptist Chapel in May 1882 she married watchmaker Joseph Hollis, “an unassuming man but a genius, residing in Ilkeston”. Joseph traded in Bath Street but had a clever, inventive mind, a man of “energy and ingenuity personified”.

Nothing in the shape of improvements seemed too difficult for Jospeh to tackle. For example in 1896 he was the inventor of the Hollis Brake, Chain and Gear, Reversible Handlebar and Folding Bicycle, complete with new ball-bearing chain wheels and frictionless gear. As he explained, although a watchmaker and jeweller by profession, “I have been for some time in the cycle trade, building my own machines, for which I find a ready sale in the Ilkeston and Nottingham districts”. He boasted that his patent Hollis Invisible Brake had book orders for 40,000 — it was designed to appeal to all cyclists, “scorcher” and “dodderer” alike. By that time Joseph had also invented an automatic bell-ringer, the bell being rung by merely giving the handle grip a quarter turn; it was capable of being fitted to any handlebar in a few minutes. And to come was the new Hollis Tubeless Tyre, “a vast improvement on all others“.

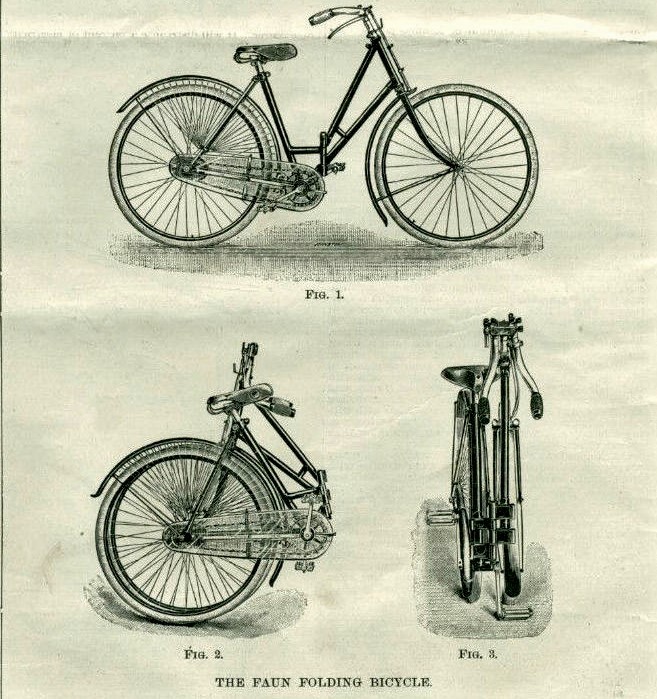

At the Nottingham Cycle Show in February 1897 Joseph put on show his new folding bicycle. His first version was a bike which separated into two parts; with his new, improved bike, just snapping a couple of catches enabled the machine to be literally folded, while a strong hinge on the upper and lower parts of the frame enabled the bike to be carried and stored compactly.

Not Joseph’s folding bike but one produced in England at the same time and using the same folding principles (Scientific American Supplement 1897)

Towards the end of the century Joseph and his family occupied Black Hills House in Stanley Street until 1898 when they left. This house had originally been built a few years earlier by George Porter Jackson, a Bath Street grocer and provision merchant, but had then been occupied by Pascal Malvern Chester, the manager at Ilkeston (Oakwell) Colliery before Joseph Hollis moved in. And Joseph moved out so its builder, George Jackson, moved in with his family. He was there until the end of the century.

May 1898 … and another trade association

The tradesmen of Ilkeston had joined together in an association for “the protection of their interests and advancement of the Borough’s prosperity“. And now was the time to sort out the ‘rules and regulations’. At a meeting at the Temperance Hall (Wilton Place) on May 24th two main issues needed to be discussed.

Firstly, should shop assistants be included in the association ? Councillor Edwin Trueman had already developed firm views on this matter — didn’t he have firm views on most matters ? For him, to include servants into the association was contrary to all precedent — if they were allowed membership then tradesmen would be swamped by male and female assistants. Perish the thought !! However the majority view which prevailed was contrary to that of Edwin.

Secondly, what was the best day for the ‘half-holiday’? Wednesday early-closing was the current custom, but this meant it presented the opportunity for many to visit neighbouring Nottingham, to shop there and so spend their money away from Ilkeston. The suggestion that Thursday afternoon as an alternative was, however, strongly resisted

———————————————————————————————————————

West’s Yard.

Adeline then asserts that “there were no more private houses (from the Sudbury premises) until you reached West’s Yard, next to Mrs. West’s drapery establishment. In this yard were two or three old cottages. Mrs. Pepper lived in one in 1850″.

In West’s Yard in 1850 were lacemaker John Pepper and his wife Ann (nee Winson), daughter of Joseph and Sarah (nee Davis).

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

And now the Marshall family. Grand Tour