Adeline introduces us to this area where we find “the Toll Bar, which was mostly in the occupation of Mr. William Campbell, the gate-keeper”.

Toll-taker William Campbell at the toll-bar gates

“On the pavement were posts forming stiles for pedestrians’ use. The long white gates stretching across the roads were kept locked. The gate looking towards White Lion Square covered the Nottingham, Stanton and Park roads. The South Street gate covered Derby Road.”

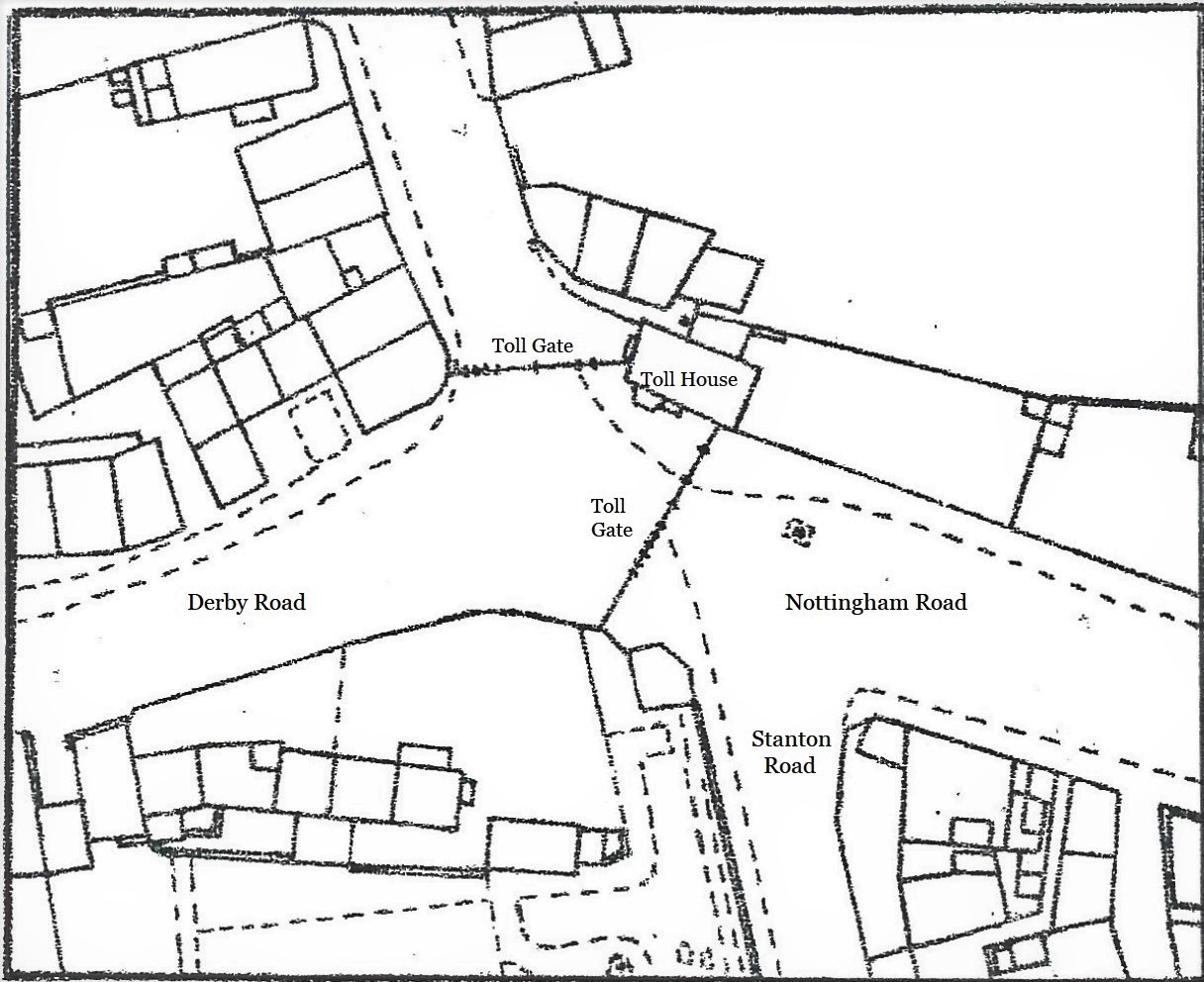

Map adapted from the Local Board map of 1866 showing the site of the toll bars and the toll house.

Local roads

In eighteenth century England many roads were in very poor condition, and sometimes and on certain routes it was quicker to walk to a nearby town than to go by coach.

The road from Nottingham to Ilkeston and on through West Hallam was so narrow in places that it could not accommodate two carriages side by side, and in winter it became almost impassable, deep with standing water and mud. Coal was not getting through to Nottingham as it should. Restricted supply and growing demand meant that the fuel was becoming very expensive, and something had to be done to facilitate its movement.

The Turnpike Trust

The role of a local Turnpike Trust was to improve and maintain a route and finance this by imposing tolls on travellers and traffic using its road. The toll-gate was where the fees were collected.

The Turnpike Age … repairing the road

Since the beginning of the eighteenth century it had been possible, by a special Act of Parliament, to set up a body of Trustees. This group would agree to construct and maintain a particular road, which might run through several parishes. Its expenses would be covered by the tolls or taxes, collected from those who then used the road. These trusts were formed at the initiative of local people not by the central ‘government’.

Thus in 1764 the Nottingham and Ilkeston Turnpike Trust was established by a group of interested local people in those two towns and other places nearby, its original intention to improve the road from Nottingham, through Wollaton, Trowell, Ilkeston, Horsley, Kilburn to Belper Lane End, with branches from Ilkeston to Shipley and Heanor, and from Trowell to Bramcote. The ‘interested local people’ included Francis Agard, a miller of Borrowash, and his son William Stringer Agard; Nottingham mill owner Robert Dennison; landowners Richard and John Dodsley Flamstead; Luke Hucknall of Risley and Lemuel Lowe of Bilborough. Squires Mundy and Newdigate were also trustees. (Waterhouse).

Parts of the original plan for the turnpike were subsequently altered when, for example, the section from Smalley Common to Belper was excluded, and further changes to its scope were made in 1784, 1804 and 1825.

As far as Ilkeston was concerned, this turnpike followed the route of Nottingham and Derby Roads.

At Ilkeston one toll bar stood across the southern end of South Street while a second one stretched across what was then Nottingham Road, but today (and since about 1889) we call White Lion Square — from Toll Bar House, in a north-eastern direction. Adeline places the toll house standing between these two toll bars, on the eastern corner of South Street where it joins White Lion Square. (see the plan above) It was demolished in 1914.

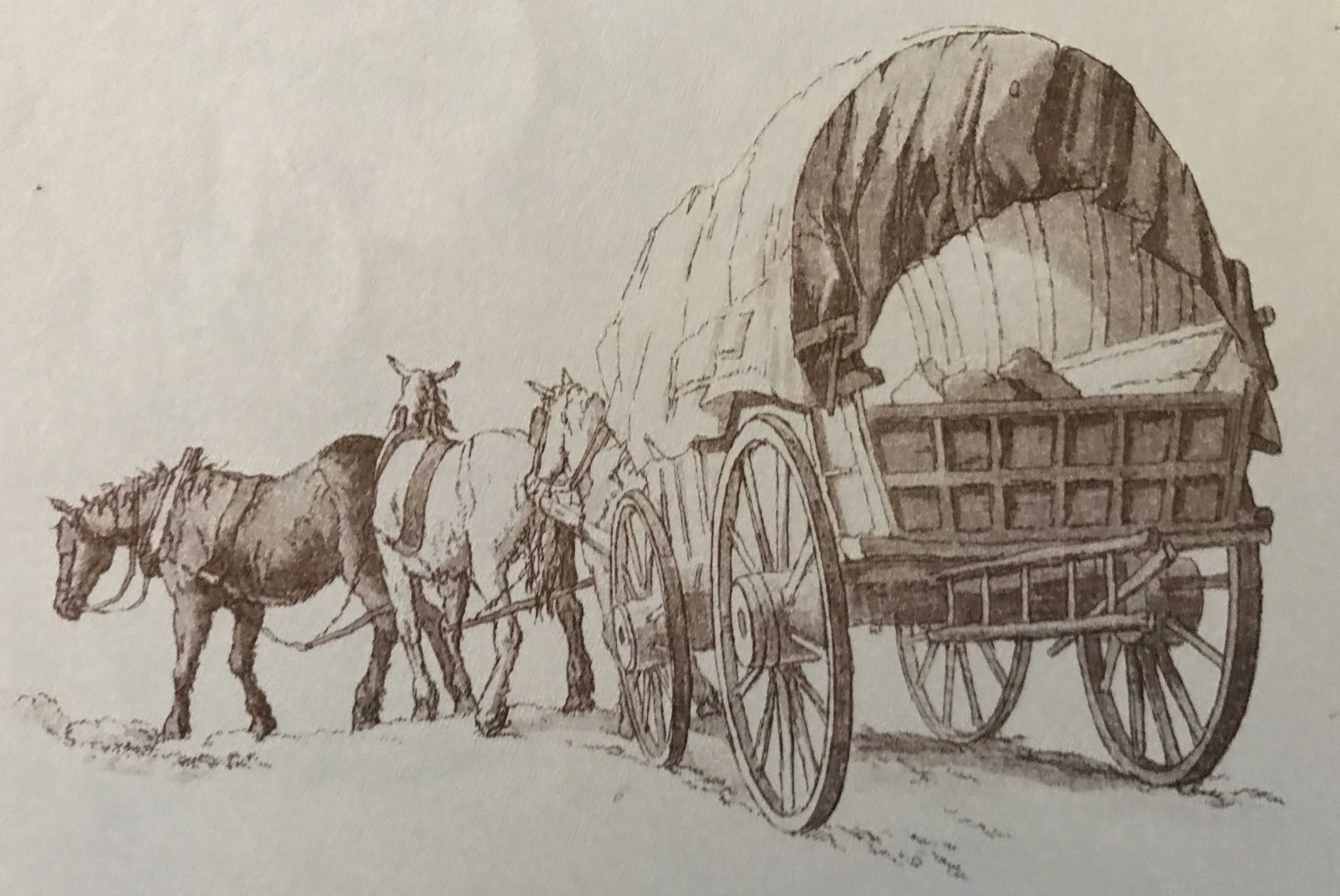

Nottingham Journal (May 26th, 1837)

The gates and chains on the road were ‘let’ for a year, their owner being determined by auction to the best bidder, as we can see in the advert (above).

For example, in 1872, the Gate and Chain at Ilkeston was let for £357. Monthly payments were then made, one month in advance.

The Turnpike Age … paying a toll

Writing in the Ilkeston Pioneer, 1934, Edgar Waterhouse let his imagination take him to the Toll Bar in the late eighteenth century ….

The gatekeeper usually wore a tall, shiney black hat, a white apron and knee breeches.

Here comes a horseman, for by horse is still the quickest and safest mode of travel. He is in a hurry and flings down 3d and gallops on.

Here comes Squire Mundy’s coach, one of the heavy, clumsy, springless coaches of the time, which even on the turnpike nearly jolt the occupants to pieces, and on the village roads are a veritable torture. It pays 3d.

It is followed by a funeral procession, the walkers passing free, but the hearse paying 3d.

Here, pulled by three horses, comes a heavy farm wagon. The gatekeeper runs his rule across the rims,and, grudgingly admitting they are over 9 inches, allows the wagon through for 2d. If they had been under 9 inches but over 6, the charge would be 3d, and if under 6 inches, 4½d. If we ask him the reason, he tells us that we ought to have sense enough to see that narrow wheels cut up the road more and make deeper ruts.

Here comes a line of packhorses, carrying coal bags slung each side, for the Erewash Canal and the Nutbrook Canal were not made till 1776 and 1793 respectively, and heavy coal carts get bogged in the 18th century roads. The drover has to pay 1d for every horse. This is duly added to the price and handed on, as usual, to the consumer.

Here, with much shouting and puffing, comes a flat, heavy cart, carrying a pair of millstones for the mill on the Erewash. It takes five horses to drag them up Trowell Bridge Road (now Nottingham Road) with many halts. They pull up at the White Lion and, while the horses stand steaming, the drivers take a well-earned pot of Henry Mosley’s home-brewed, for the brewers do not yet own the house, though they are soon to do so, for in 1811 Samuel and Benjamin Deverill, brewers of Nottingham, bought the inn…..

Here cames Sam Fish, an Ilkeston drover, with a herd of cows and sheep. The cows cost him 10d a score, and the calves, sheep and lambs 5d a score.

The gatekeepers had a bad reputation for dishonesty, but we are only foot passengers, so we pass through the small gate at the side, free of charge, and proceed on our way up the left-hand or west side of South Street , towards the Market Place.

In the 1850’s by the toll-gate was a large board, 6 feet by 2 feet, bearing the date April 13th 1825.

It itemised the charges for coaches, gigs, hearses, horses, droves of cows, oxen, calves, sheep, lambs and so on, if they wished to pass through the gate. The signature on the board was that of Hugh Bruce Campbell, Scottish solicitor of the Rope Walk, Nottingham. In 1853 he became the new clerk of the Trust, a post he held until his death in 1863. His position was then taken by Nottingham solicitor Walter Browne.

Toll disputes

In the late 1850s John Tidd Pratt, lawyer and counsel, gave his learned opinion that the powers of the Commissioners of the Nottingham and Ilkeston Turnpike had ceased in 1856, and since that time several travellers had attempted to pass through the Ilkeston Bar without paying the toll. One of the tactics employed by toll-keeper William Campbell was to keep the gate closed and then negotiate with the recalcitant traveller, but for a while he seems to have given up the ghost, kept the gate open and allowed free access. But not always !! This depended upon who was trying to escape payment, so that there were still numerous disputes over the toll charges. Many of them ended in a court case.

For example, in May 1864 horsebreaker Charles Hampson of High Street was charged by William Campbell with toll evasion.

On horseback, Charles had been on his way to visit wheelwright Joseph Scattergood in Market Street and a court witness claimed to have seen him on the Ilkeston to Nottingham turnpike, turning off South Street into Gladstone Street, just before the pawnbroking establishment of John Moss. The latter street was a very dilapidated private road at that time, not used as a public highway but its surface was partially made up and had houses along part of it. Charles claimed to have never used the turnpike and his evidence convinced the magistrates who dismissed the case.

At the same court the horsebreaker also discovered that he had been toll-charged illegally in the past. On five occasions he had taken a horse through the toll-gate to have it shod at the blacksmith’s shop just 20 yards away from the gate, but because it was saddled he had been charged one penny ha’penny each time. He now learned that he was entitled to go a distance of two miles for such an errand, without charge!

He also learned that he was not to be compensated with expenses for travelling from Lincoln to attend the court!!

The blacksmith to whom Charles was taking his horse might have been William Bell junior at the Travellers’ Rest Inn?

The Turnpike Age … farriers at work

At the same court James Dutton was charged with the same offence as Charles.

Accompanied by his son, James had come from West Hallam with two carts of coal and had turned off Derby Road at Belper Street to deliver one load at the house of labourer James Lester. The two carts then came out of the street and on to Little Hallam where the Duttons lived, thus by-passing the toll-bar, but toll collector William declared that they had no right to use this route with horse and cart and were merely trying to avoid the toll.

After argument over who was in charge of the offending vehicle, William again lost his case.

The Turnpike Age … carting goods

In the following year, William Campbell was facing his nemesis — contractor William Hancock of Kirk Hallam — at Ilkeston Petty Sessions. The toll collector charged the contractor with illegally leaving goods unattended on the Nottingham and Ilkeston turnpike road but unfortunately arrived at court too late to press his case, only to learn the charge had been dismissed.

The magistrates told him off — if they were to wait until it suited him to arrive then they might be waiting all day!!

What made matters worse for William C was that he now faced a claim from William H for overcharging on the same turnpike.

There had been a long-running feud between the two, with the contractor evading the toll at every opportunity, blatantly baiting William C and making his life a misery. The toll-collector was spitting nails and although he might have overcharged, it was no more than the other William H deserved. The magistrates disagreed however and the matter was settled with both sharing the costs.

The demise of the Turnpike Trust

from the Ilkeston Pioneer October 8th 1874

October 31st 1874 marked the end of the 111-year history of the Nottingham and Ilkeston Turnpike Trust.

The Pioneer was gleeful.

“Ilkeston Toll-Bar is no more! The Turnpike Trust expired on Saturday night last and on Sunday morning scarcely a stick of the bar was to be seen – gates, and all the chief posts, having taken a moonlight flight”.

Quick to spot a bargain, nearby resident Ralph Shaw had purchased the two now redundant toll-gates ‘with all their appurtenances’. Tolls were collected as usual during the day but at about nine o’clock in the evening ‘demolition’ began, and by half past 10 both gates had been taken, along with the pallisading on either side.

Following the Sunday rest-day, the removals continued on Monday when ‘the last vestige of the bar’ disappeared.

And the Pioneer continued its celebration; “the extinction of the tolls, and the removal of the bar, are subjects of general gratification to the inhabitants of Ilkeston and the neighbouring villages, and will tend greatly to improve the value of property in South-street and the Nottingham-road, and open the way to several improvements in the locality”.

Rival newspaper, the Ilkeston Telegraph, noted one, more immediate, benefit. “The gatehouse is being taken down for the purposes of reducing the curve, and otherwise improving the road”.

The good mood was not to last however. Three weeks later and the Pioneer had found something to criticise, and once more the Local Board was in its line of fire.

“Only a white-washed wall now remains – a solitary remnant – to betoken to the stranger where once stood the Ilkeston Toll-bar. But it appears that the disappearance of one nuisance leads to the creation of another; for the road has been so hacked up that a shower of rain makes it into such a puddle that pedestrians are not able to cross except by wading a considerable depth in mud. If the Local Board would see to this they would be doing good services”.

Had ‘the last vestiges’ disappeared? In 1910 two old posts which held the toll-gate could still be seen on at the south end of South Street, between Shaw’s butcher’s shop and Shaw’s saddler’s shop. The Pioneer (1932) records that the last relic of the old toll gate was one of the posts which stood alone for some time at the bottom of South Street, on the right-hand side in the direction of Nottingham and Derby.

Another post was planted doing a like duty, down Park Road, just above the memorial houses. (IA 1910)

Shortly after the demise of the toll bar, in May 1875, William Campbell was appointed Inspector of Nuisances for the Local Board, for one year, at an annual salary of £60.

————————————————————————————————————————————–

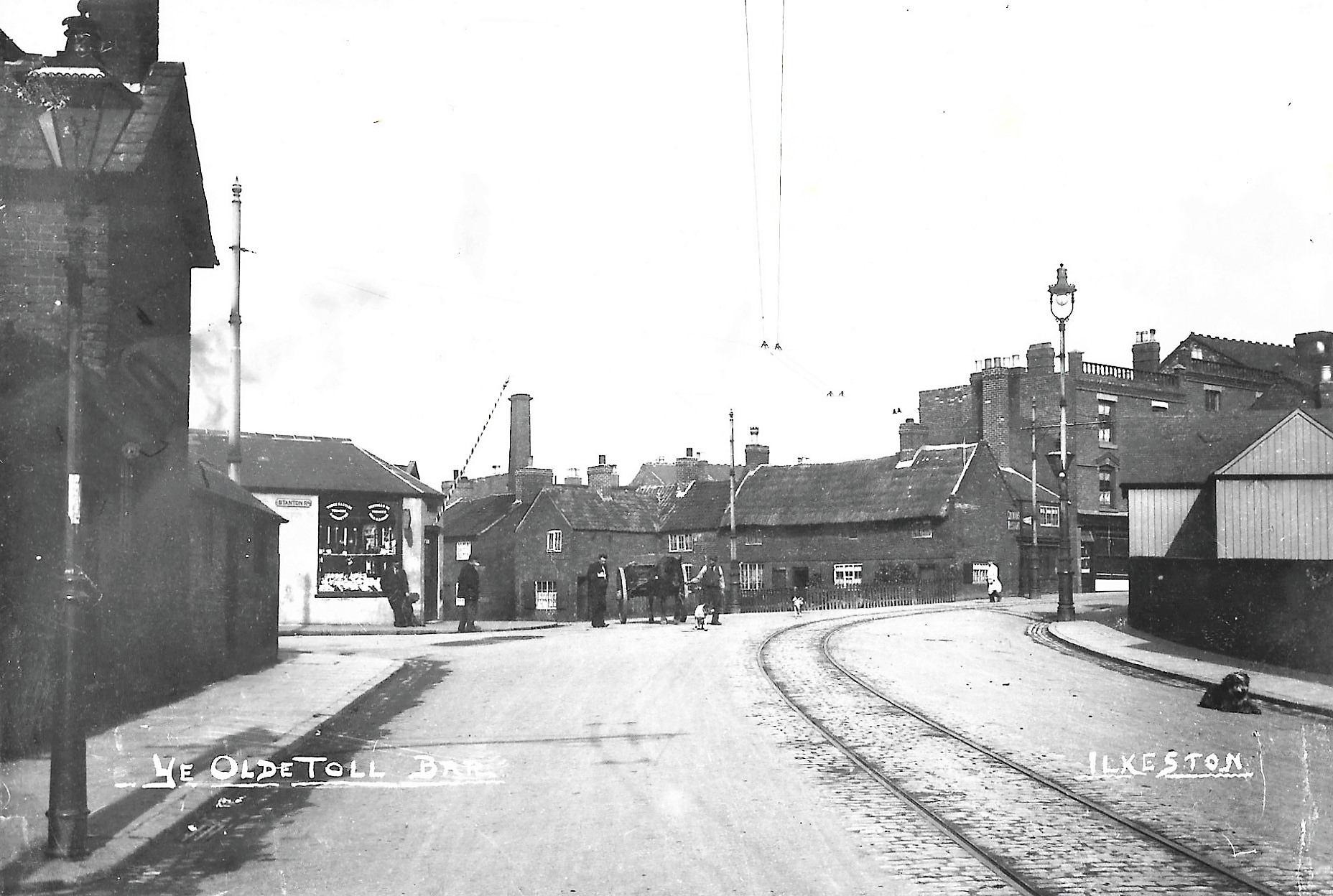

a postcard image of the area dated c1905 (Jim Beardsley collection)

Stanton Road on the left, the entrance to Derby Road in the centre, and South Street on the right. The first of the Chain Row cottages can be seen below the factory chimney.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

William Campbell, tailor, toll-taker and town poet

“The toll house was on the East side and between the two gates. Mr. William Campbell had charge of the toll bar for many years. When Belper Street was opened a chain was put across Derby Road just below the present Albert Street, and Mr. Campbell had to unlock it when vehicles came Belper Street way. He was a tailor and plied his business at home”.

We have met William Campbell at Carrier’s Buildings alias Pleasant Place further along South Street towards the Market Place.

He was the son of tailor William senior and Ann (nee Gregory) and had married Elizabeth Plackett on October 15th, 1834. They had one daughter, Louisa, born on September 24th, 1838 at Breaston, Derbyshire. (Both Elizabeth and daughter Louisa then disappear from my view; what happened to them ?

William’s second wife was Sally Elizabeth Outram, the eldest daughter of land surveyor, maltster and publican John and Lucy (nee Fletcher). By the 1841 census both of her parents had died in Ilkeston, and Sally Elizabeth was living with her grandmother. The latter was born Elizabeth Glover and had married William Fletcher at Heanor Parish Church on March 24th, 1788. (Lucy Fletcher, who married John Outram, was the youngest of the subsequent four Fletcher children).

When William Fletcher died his widow remarried to widower Thomas Porter, a cottager who lived in Nottingham Road. The 1841 shows Thomas and Elizabeth Porter living there, with Elizabeth’s unmarried granddaughters Sally Elizabeth, Lucy and Elizabeth Ann Outram. Also in the household was six-year-old William Outram, the illegitimate son of Sally Elizabeth. Sadly William does not appear on the following censuses. In September 1842, while riding on a cart, William fell off and was fatally crushed by the cart’s wheel.

The Campbell children

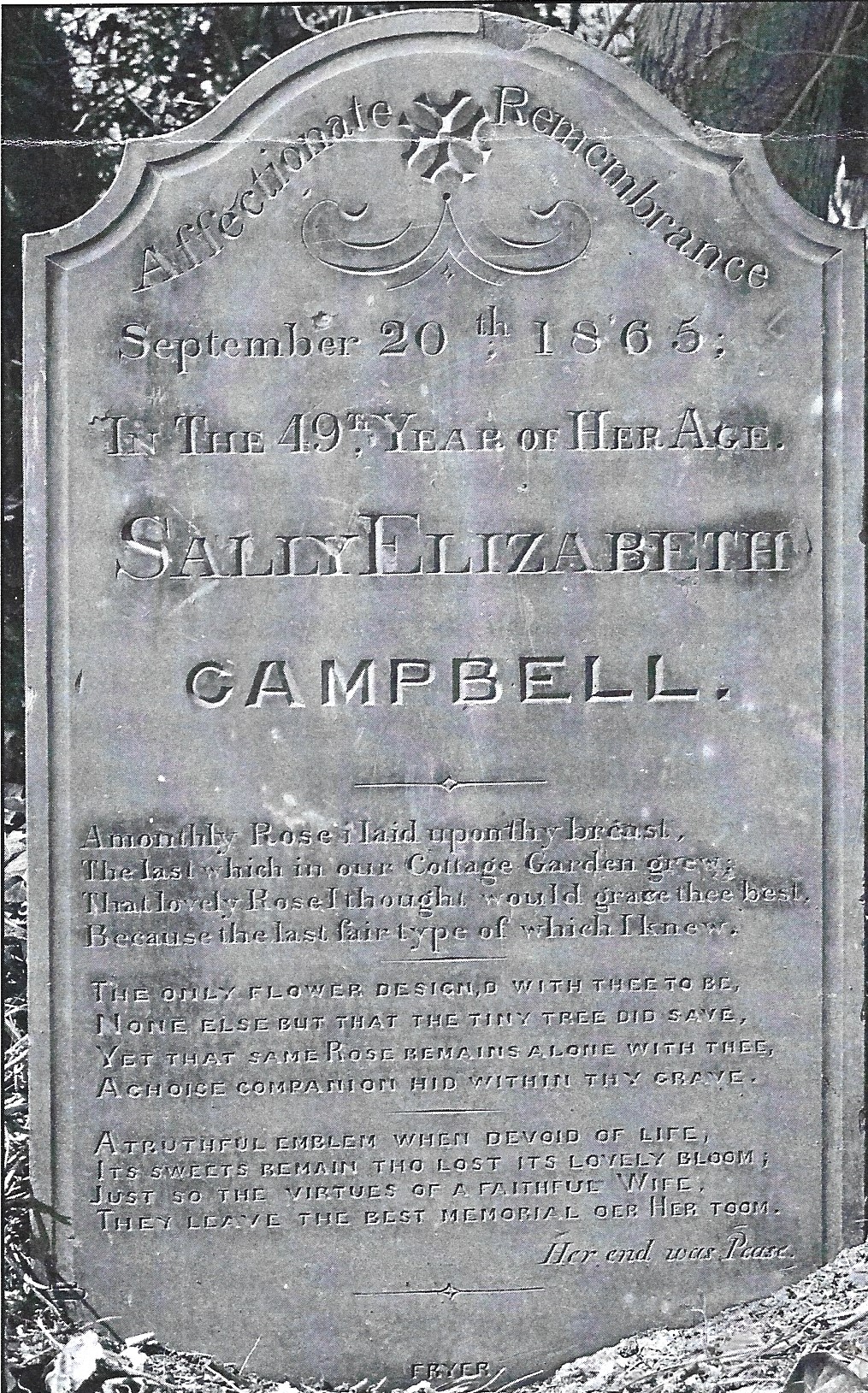

Sally Elizabeth Campbell died on September 20th, 1865 and was buried in St. Mary’s church graveyard extension. Most likely the verses of poetry on her stone were composed by her husband.

Adeline tells us that “Mrs. Campbell died, leaving him with two daughters, Lucy and Annie”. But there were other children.

The couple’s first child, William Fletcher Cambell, had died aged seven months when accidentally scalded by an overturned pancheon of boiling herb beer. At the time he was being minded by a ‘nurse’, a girl about five years old.

“Daughter Lucy married Mr. Stephen Barnes” recalls Adeline. She was their second child and married Stephen Barnes, blacksmith son of Elias and Hannah (nee Mason) in March 1881.

The Barnes family arrived from the Gedling area of Nottingham in the early 1850’s and when Lucy married into it she joined the household in Stanton Road.

However the following year was to prove a very sad one for the Barnes family.

On February 18th 1882 Lucy gave birth to a daughter but then died of puerperal fever on March 4th followed by her unnamed daughter on March 12th. And on December 10th Stephen died of meningitis, aged 37.

All were buried close together in the General Cemetery in Stanton Road.

At her death, Lucy’s father informed the readers of the Advertiser that his daughter had been born, been married and died in the month of March. He also expressed his thanks to all in the neighbourhood for lowering the blinds of their dwellings until after her funeral.

Daughter “Annie was in domestic service”. She was for many years a domestic servant in the household of Francis Sudbury, hosiery and glove manufacturer, at first in Market Street and later at Field House. And it was in Market Street that her illegitimate son George Bell Campbell, was born in February 1873. The latter was present when his grandfather William Campbell died in Weaver Row on January 25th 1890, aged 85.

Daughter Elizabeth, twin of Annie, died of scarlatina in February 1858, aged four years.

The former Toll Bar Cottage at the junction of White Lion Square (right) and South Street ( left) …. was demolished in June 1914. (courtesy of Ilkeston Reference Library)

This was not the original toll bar gatehouse which was dismantled in November 1874, shortly after the closure of the Toll-Bar and the end of the Turnpike Trust.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

We are at Toll Bar corner.