After the two bankrupt tradesmen, Adeline brings us to “Mr. William Henshaw, fishmonger. This shop was, I believe, the oldest in Bath Street. The rooms were very low and dark, with the bank close to the back door, so that candles had to be used during the day, and the entrance to the shop was lower than the street”.

William Henshaw, senior (1822-1908)

Born on September 26th, 1822 William Henshaw was the son of William and Betty (nee Fletcher) and like his father, converted to fishmonger after working as a framework knitter. In 1844 he married an Ilkeston lass, Mary (nee Matthews), the widow of lace manufacturer William Wilkey. She was the daughter of Shipley coalminer Thomas and Elizabeth (nee Harrison).

By 1857 William Henshaw had a criminal record. He had been convicted of embezzlement and in 1849 of stealing linen from Henry and Jane Ludlam which he pawned in Nottingham and for which crime he received a six months prison sentence with hard labour. (The Ludlams were in the process of leaving the Gallows Inn, where Henry had recently been the tenant landlord, They had entrusted a large chest of belongings to William’s fae keeping but he had felt empowered to pawn a selection of their belongings, without thier consent !!)

And in January of 1857 William was again in the witness box but this time giving evidence against Henry Spencer.

William had bought guinea fowls from the latter and sold them to customers in and around the town. Unfortunately they were not the property of Henry to sell but of William Bentley of Purday House in Shipley. The accused denied the theft, stating that after a hard day’s work at West Hallam furnace, the last thing he wanted to do was go out stealing at night. The jury found him guilty and he spent the next six months in prison where at least he would find relief from his furnace work !

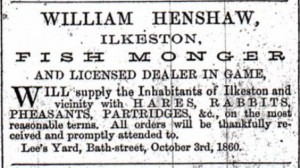

From the Ilkeston Pioneer of November 1860, when William was trading at his home in Lee’s Yard, later Albion Place.

In late 1862 William was granted a renewal of his licence to deal in game but only from his cart-stall which stood outside his shop and not from within the shop.

This didn’t shield him from trouble two years later, when he was charged with selling game at his stall without a display board stating that he was licensed to do so.

William couldn’t deny it but he had his excuse ready. He said that he had recently repainted his stall and hadn’t had the time to add his name and licence to it.

Not good enough for the magistrates! A fine of 1s and 10s 6d expenses.

A short time later and William was back in court again, having been ‘grassed up’ by the Burgin brothers of Mount Street, Thomas and Samuel, whom we have recently met and who were rival dealers in game. They had seen William sell hares to wheelwright Thomas Severn of High Street and to John Barker, landlord of the Bridge Inn on Awsworth Road, from within the shop. This was contrary to the conditions of his game licence. However the two recipients of the alleged illegally purchased game declared that the game had been bought from the stall which was standing between the shops of Messrs Henshaw and Wood.

The magistrates, while dismissing the charge, thought that William was using dubious sales methods and warned him of his future behaviour. This might count against him when his licence was up for renewal.

Still trading in 1893, but now at 57 North Street, William was granted a licence to sell game daily from a Market Place stall. He was then aged 71.

William Henshaw, junior (abt 1840-?)

“His son William and daughter Augusta, helped their father in the business”.

‘Son William’ was in fact step-son Albert William Wilkey born in 1840 who later in life took the name of William Henshaw.

He was also known as William Matthews — his mother’s maiden name — alias ’Pussy’.

By 1868 William junior had been turned out of the Henshaw home and in 1869, under the name of Matthews, he too found himself in court. There he was charged with aiding and abetting his cousin Joseph Clower — reported in the local press as John Clower — in the robbery of ten guineas from the East Street home of their grandfather, Thomas Matthews.

Joseph (John) pleaded guilty at the magistrates’ court and was sentenced to six months hard labour.

William however protested his innocence and was committed for trial at Derbyshire Quarter Sessions where he was found guilty and received eight months in jail with hard labour — not his first nor last ‘brush with the law’.

William junior married Wolverhampton born Mary Loftus in December 1870, and she was also often of great interest to the police.

We have seen how – in 1866/67 — an episode at Club Row led to her imprisonment and only a year later she was in the dock again, at Ripley Petty Sessions, charged with robbery.

At court Mapperley collier Alfred Faircourt related how he had found himself with a few pounds in his pocket, having recently sold a pig, but had made the mistake of stopping in Ilkeston Market Place to view a fight that was taking place there. As he looked on he was approached by Mary who ….the remainder of his testimony was of an extremely disgraceful nature !!…. but the result was that he claimed to have been robbed by Mary.

This time however the evidence was insufficient and she was acquitted.

A similar verdict was reached almost exactly a year later when Mary was accused of aiding and abetting a robbery. (See Clarkson, Tooth and Pickburn).

A few months before her marriage in December 1870, and approaching midnight Mary was out and about in Bath Street, drunk and riotous, allegedly throwing stones at the shutters of her prospective father in law‘s shop.

She admitted being drunk, … but riotous? — never!!

The magistrates disagreed with her however and because of Mary’s long list of previous convictions she was fined 40s with 10s 6d costs, or two months imprisonment with hard labour.

At that time the Ilkeston Telegraph styled her as ‘an old offender and common prostitute’.

And just a few months hiatus before she was again in bother, this time after spreading malicious rumours about the chastity of collier Wheatley Straw’s wife. He took exception to Mary’s stories but felt much better after clobbering her with a few blows.

Again more ‘disgusting’ evidence was heard at the Petty Sessions where the magistrates decided that the miner must be fined.

In October and November of 1874 William junior and Mary Henshaw were back in trouble.

Firstly, at the end of October, William was charged by Louisa Dawes (nee Lacey), wife of coalminer Samuel, with assault and using threatening language, such that she feared for her life.

She had encountered William in a pub — where else?! — when he threatened to ‘stick her’ and promptly did so.

Despite pleading provocation, for the assault William was fined 5s with costs and for his menacing language he was bound over in the sum of £20 to keep the peace for six months.

William’s wife Mary was obviously not a believer in the proverb “revenge is a dish best served cold”.

Almost immediately she had sought out Louisa for ‘lawing her husband’ and if he would not kill her, she would.

Retribution came at the Market Inn.

As Louisa was walking down a passage there, Mary emerged from the tap-room and struck her several times.

A short time later and Louisa was recovering close by the Inn when both of the Henshaws approached her. William held her while Mary once more practiced her pugilistic skills on Louisa’s face and rendered her insensible for some time.

Throughout the hearing at the Petty Sessions Mary referred to the magistrates as ‘my dear’ but this did not save her from a fine of 2s 6d with costs.

Mary could not pay …. “I’ve got no money”.

The alternative was 21 days in prison with hard labour:

“Twenty-one days – I’ll do that”.

And she did.

April 1875 and another fine for Mary after an assault on Caroline Eaton (nee Bell).

The winter of 1875/76 was an eventful one for William junior.

At the end of November he was once more at Ilkeston Petty Sessions, charged with theft.

Carpenter Job Smith, who was working on a new railway line at Ilkeston, was housed in a temporary hut adjoining his works with several other labourers. One Friday morning, William entered, selling fish.

Shortly after he left, Job noticed that his silver watch and chain had also left. He immediately informed the police.

That afternoon the railway navvy accompanied P.C. Booth to William’s house where the missing watch was handed over by William’s half-sister Augusta Thompson. But William hadn’t stolen the watch; he had found it!!

The P.C. knew of William’s reputation for doing ‘very clever tricks as a conjurer’ at the local pubs, implying that he could have light-fingeredly lifted the watch and chain without anyone knowing. However by this time Job wasn’t sure what had happened to his watch and thought he might have lost it.

And there the matter rested.

That is, until two days later — by which time Job had sworn out a warrant against William.

Armed with this and accompanied by his sergeant William Colton, P.C. Booth went in search of William and found him in a beerhouse – where else? – with his wife Mary and half-sister Augusta.

William was not in the mood to go quietly. Nor were his two relatives willing to calm him down. The three of them laid into the sergeant, grappling and kicking inside the alehouse and lurching outside into the street where the wrestling match continued for some time – until William was dragged off to the lock-up.

On the charge of theft he was remanded on bail, to appear at Derby Quarter Sessions in January. The sureties for his bail were William Henshaw (his father?) and James Henshaw (his uncle?)

On the charge of assaulting a policeman in the execution of his duty he was to spend New Year’s Day — and several others — in prison. Co-defendants Mary and Augusta were fined.

When the charge of theft of the watch and chain was brought to the Derby Court in January 1876 there were serious flaws in the prosecution case and William was very soon discharged.

And very soon in trouble again.

In July 1876 William was now lodging with the Skeavingtons at Mount Row when he was charged with threatening Eliza Skeavington so that she was ‘in bodily fear’.

The latter had given William notice to quit the house but he had refused to leave and had threatened to cut her throat — not the first time that he had menaced her.

William however claimed that it was Eliza’s mother Keziah Skeavington (nee Yasley) who was the head tenant of the house and she did not wish William to leave.

Eliza had no right to order him out. And anyway he hadn’t made any threats.

At the Petty Sessions he was bound over to keep the peace for six months – which seemed to be the maximum amount of time that William could steer clear of trouble.

By January 1879 William junior and Mary had had four children, three of whom had died in infancy. The surviving daughter was Mary Augusta, born in November 1875 and who was to die in May 1882 at the Bath Street home — Number 13 — of her grandfather William senior.

By September 1879 William junior was living at this same house, with his mother and step-father. Ten-year old Alice Briggs – a daughter of John and Ann (nee Hutchinson) – lived just round the corner in Club Row and acted as a servant for the Henshaw household, and a temptation for William junior.

Thus, a month later the fishmonger was defending himself at Ilkeston Petty Sessions on a charge of indecent assault on Alice. He called his ‘father’, mother and aunt as witnesses, to agree with him that Alice was a girl of ‘very bad’ character, and attempted to explain that his drunkenness had caused his aberrant behaviour.

It didn’t ‘wash’ with the magistrates. William was found guilty.

Because of previous convictions against him, he was sentenced to three months imprisonment with hard labour.

Gap alert!!

Where was William junior lurking on the 1881 Census?

His wife Mary was lodging in Wakefield’s Yard at the house of Irishwoman Mary Grady. She was described as a married costermonger (street seller). But no sign of William.

In the same house was Mary’s younger sister Catherine/Kate, the wife of labourer William James.

In October 1881 William junior and his brother-in-law Arthur Tissington Thompson were in the Miners’ Arms on Derby Road.

A young woman and her two children were about to sing for the customers and William – ever the gentleman – called for order.

But there’s always one, isn’t there??

In this case it was Edwin Berresford, attired in the uniform of the Ilkeston Fire Brigade, who continued to be rather noisy and hold up the performance. When a somewhat drunken William remonstrated with him, the fireman punched him in the face and general pandemonium ensued.

Kicks were aimed, beer pots became weapons, cans flew around and heads were banged, including those of Edwin and of the landlord, Joseph Childs.

A few days later Edwin turned up at the Petty Sessions, his head dressed with plaster, arguing that he was the injured party. Witnesses also testified that both William and Arthur had been drunk and responsible for his injuries, but — unfortunately for Edwin — the landlord did not wish to prosecute the two brothers-in-law, and the fireman was left to ‘carry the can’.

The magistrates decided that publicans must be supported in keeping order in their houses and Edwin was fined one shilling for his assault on Joseph.

Half-sister of William Henshaw junior, Augusta was the only one of four Henshaw daughters to live beyond childhood.

She married fishmonger and game dealer Nottingham-born Arthur Tissington Thompson in March 1872 who was a ‘well-known character in Ilkeston’ — that is well-known for drunkenness and court convictions. The latter reduced his income while the former reduced his life expectancy.

Arthur’s excessive drinking caused his premature death – at the age of 38 – in August 1891.

——————————————————————————————————————————

And now we walk on to meet Simon Clarkson, chemist